Judging (or Evaluating)

Literary criticism is also concerned with such questions as these: Is Macbeth a great tragedy? Is Macbeth a greater tragedy than Romeo and Juliet? The writer offers an opinion about the worth of the literary work, but the opinion must be supported by an argument, expressed in sentences that offer supporting evidence.

Let’s pause for a moment to think about evaluation in general. When we say “This is a great play,” are we in effect saying only “I like this play”? That is, are we merely expressing our taste rather than asserting something independent of our tastes and feelings? (The next few paragraphs won’t answer this question, but they may start you thinking about your own answer.) Consider these three sentences:

It’s raining outside.

I like vanilla.

This is a really good book.

If you are indoors and you say that it is raining outside, a hearer may ask for verification. Why do you say what you say? “Because,” you reply, “I’m looking out the window.” Or “Because Jane just came in, and she is drenched.” Or “Because I just heard a weather report.” If, however, you say that you like vanilla, it’s almost unthinkable that anyone would ask you why. No one expects you to justify — to support, to give a reason for — an expression of taste.

Now consider the third statement, “This is a really good book.” It is entirely reasonable, we think, for someone to ask you why you say that. And you reply, “Well, the characters are realistic, and the plot held my interest,” or “It really gave me an insight into what life among the rich [or the poor] must be like,” or some such thing.

That is, statement 3 at least seems to be stating a fact, and it seems to be something we can discuss, even argue about, in a way that we cannot argue about a personal preference for vanilla. Almost everyone would agree that when offering an aesthetic judgment we ought to be able to give reasons for it. At the very least, we might say, we hope to show why we evaluate the work as we do and to suggest that if readers try to see it from our point of view they may then accept our evaluation.

Evaluations are always based on assumptions, although these assumptions may be unstated, and in fact the writer may even be unaware of them. Some of these assumptions play the role of criteria; they control the sort of evidence the writer believes is relevant to the evaluation. What sorts of assumptions may underlie value judgments? We will mention a few, merely as examples. Other assumptions are possible, and all of these assumptions can themselves become topics of dispute:

A good work of art, although fictional, says something about real life.

A good work of art is complex yet unified.

A good work of art sets forth a wholesome view of life.

A good work of art is original.

A good work of art deals with an important subject.

Let’s look briefly at these views, one by one.

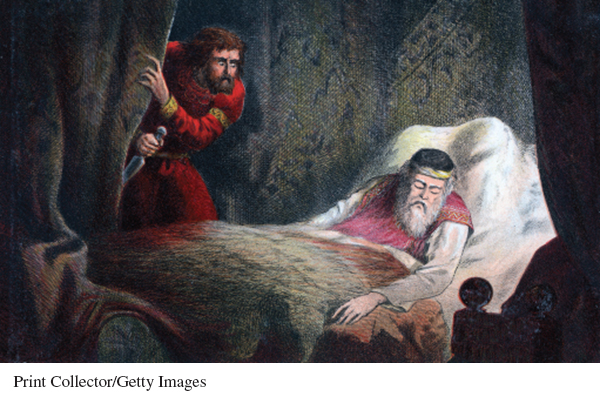

1. A good work of art, although fictional, says something about real life. If you hold the view that literature is connected to life and believe that human beings behave in fairly consistent ways — that is, that each of us has an enduring “character” — you probably will judge as inferior a work in which the figures behave inconsistently or seem to be inadequately motivated. (We must point out, however, that different literary forms or genres are governed by different rules. For instance, consistency of character is usually expected in tragedy but not in melodrama or in comedy, where last-minute reformations may be welcome and greeted with applause. The novelist Henry James said, “You will not write a good novel unless you possess the sense of reality.” He’s probably right — but does his view hold for the writer of farces?) In the case of Macbeth you might well find that the characters are consistent: Although the play begins by showing Macbeth as a loyal defender of King Duncan, Macbeth’s later treachery is understandable, given the temptation and the pressure. Similarly, Lady Macbeth’s descent into madness, although it may come as a surprise, may strike you as entirely plausible: At the beginning of the play she is confident that she can become an accomplice to a murder, but she has overestimated herself (or, we might say, she has underestimated her own humanity, the power of her guilty conscience, which drives her to insanity).

2. A good work of art is complex yet unified. If Macbeth is only a “tyrant” (Macduff’s word) or a “butcher” (Malcolm’s word), he is a unified character, but he may be too simple and too uninteresting a character to be the subject of a great play. But, one argument holds, Macbeth in fact is a complex character, not simply a villain but a hero-villain, and the play as a whole is complex. Macbeth is a good work of art, one might argue, partly because it shows us so many aspects of life (courage, fear, loyalty, treachery, for a start) through richly varied language (the diction ranges from a grand passage in which Macbeth says that his bloody hands will “incarnadine,” or make red, “the multitudinous seas” to colloquial passages such as the drunken porter’s “Knock, knock”). The play shows the heroic Macbeth tragically destroying his own life, and it shows the comic porter making coarse jokes about deceit and damnation, jokes that (although the porter doesn’t know it) connect with Macbeth’s crimes.

3. A good work of art sets forth a wholesome view of life. The general public widely believes that a work should be judged partly or largely on the moral view that it sets forth. (Esteemed philosophers, notably Plato, have felt the same way.) Thus, a story that demeans women — perhaps one that takes a casual view of rape — would receive a low rating, as would a play that treats a mass murderer as a hero.

Implicit in this approach is what is called an instrumentalist view — the idea that a work of art is an instrument, a means, to some higher value. Thus, many people hold that reading great works of literature makes us better — or at least does not make us worse. In this view, a work that is pornographic or in some other way considered immoral will receive a low value. At the time we are writing this chapter, a law requires the National Endowment for the Arts to take into account standards of decency when making awards.

Moral judgments, it should be noted, do not come only from the conservative right; the liberal left has been quick to detect political incorrectness. In fact, except for those people who subscribe to the now unfashionable view that a work of art is an independent aesthetic object with little or no connection to the real world — something like a pretty floral arrangement or a wordless melody — most people judge works of literature largely by their content, by what the works seem to say about life.

Marxist critics, for instance, have customarily held that literature should make the reader aware of the political realities of life.

Feminist critics are likely to hold that literature should make us aware of gender relationships — for example, aware of patriarchal power and of women’s accomplishments.

4. A good work of art is original. This assumption puts special value on new techniques and new subject matter. Thus, the first playwright who introduces a new subject (say, AIDS) gets extra credit, so to speak. Or to return to Shakespeare, one sign of his genius, it is held, is that he was so highly varied; none of his tragedies seems merely to duplicate another, each is a world of its own, a new kind of achievement. Compare, for instance, Romeo and Juliet, with its two youthful and innocent heroes, with Macbeth, with its deeply guilty hero. Both plays are tragedies, but we can hardly imagine two more different plays — even if a reader perversely argues that the young lovers are guilty of impetuosity and of disobeying appropriate authorities.

5. A good work of art deals with an important subject. Here we are concerned with theme: Great works, in this view, must deal with great themes. Love, death, patriotism, and God, say, are great themes; a work that deals with these may achieve a height, an excellence, that, say, a work describing a dog scratching for fleas may not achieve. (Of course, if the reader feels that the dog is a symbol of humanity plagued by invisible enemies, then the poem about the dog may reach the heights; but then, too, it is not a poem about a dog and fleas: It is really a poem about humanity and the invisible.)

The point: In writing an evaluation you must let the reader know why you value the work as you do. Obviously, it is not enough just to keep saying that this work is great whereas that work is not so great; the reader wants to know why you offer the judgments that you do, which means that you

must set forth your criteria, and then

offer evidence that is in accord with them.