ALFRED EDMOND JR.

Alfred Edmond Jr. (b. 1960) is senior vice president/multimedia editor-at-large of Black Enterprise, a media organization that publishes Black Enterprise magazine. He appears often on television and on nationally syndicated radio programs. The following essay was originally published in Black Enterprise in 2012.

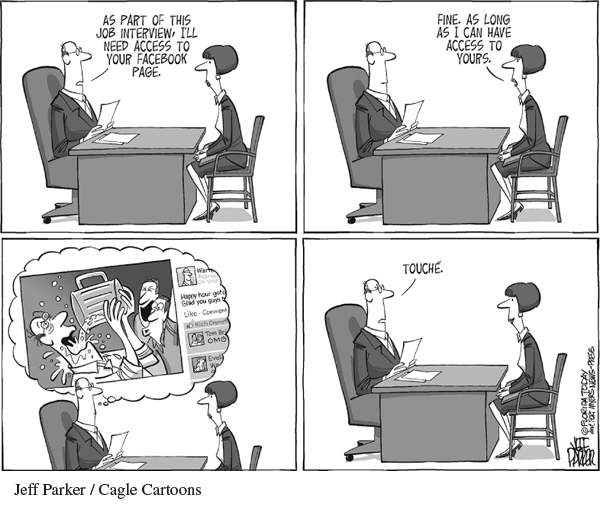

Why Asking for a Job Applicant’s Facebook Password Is Fair Game

“Should business owners be allowed to ask job applicants for their Facebook passwords?” Many people who watched me on MSNBC’s Your Business on Sunday were surprised to hear that my answer is “Yes,” including the show’s host, J. J. Ramberg. This question became a hot news topic last week, especially in business and social media circles, when Congress failed to pass legislation that would have banned the practice of employers asking employees to reveal their Facebook passwords.

Now, if I was asked the same question as a guest on a show called Your Career, I would have been hard-pressed to think of a situation where I would share my Facebook password with a potential employer. For me to consider it, I would have to want the job pretty badly, with the amount and type of compensation (including benefits, perks, and even an equity stake in the company) being major considerations. But before doing so, I would see if there were other ways I could address the potential employer’s concerns without revealing my password, such as changing my privacy settings to give them the ability to view all of my Facebook content. If they persisted with their request for my password, I would try to negotiate terms to strictly limit both their use of the password and the length of time the potential employer would have access to it before I could change it. I might even consider getting an employment attorney to negotiate an agreement, including terms of confidentiality, to be signed by both me and the potential employer before sharing my password.

Of course, for the vast majority of positions, neither I nor a company looking to hire would deem it worth the time and expense to jump through all of these hoops. Most companies would not care to have password access to an applicant’s social media accounts. (For what it’s worth, Facebook’s terms of rights and responsibilities forbids users from sharing their passwords.) In probably 99 percent of such cases, if a potential employer made such a request, my answer would be, “No, I will not share my password. Are there alternatives you are willing to consider to satisfy your concerns?” I’d accept that I’d risk not being hired as a result. On the other hand, if that was all it took for me not to be hired, I’d question how badly they really wanted me in the first place, as well as whether that was the kind of place I would have been happy working for. But for certain companies and positions, especially if I wanted the job badly enough, I’d consider a request for my Facebook password at least up for negotiation.

That said, my response on Your Business was from the perspective of the business owner. And if I’m the owner of certain types of businesses, or trying to fill certain types of positions, I believe I should be able to ask job applicants for access to their Facebook accounts. The applicant may choose not to answer, but I should be able to ask. Depending on the position, knowing everything I possibly can about an applicant is critical to not only making the best hire, but to protecting the interests of my current employees, customers, and partners as well as the financial interests of the company.

5 On Your Business, I pointed to an example where I believe a request for a Facebook password as part of the hiring process is entirely reasonable: the child care industry. If I am running a school or a day care center, the time to find out that a teacher or other worker has a record of inappropriate social media communication with minors, or worse, a history of or predilection for sexual relationships with students, is during the hiring process — as New York City is finding out the hard way, with an epidemic of public school employees being revealed to have had such relationships with students. To me, such a request falls into the same category of checking the backgrounds of potential employees as the common (also still debated) practice of asking job applicants to agree to a credit check, especially for jobs that will require them to handle money, keep the books, or carry out other fiscal duties on behalf of a company. In these and other cases, safety and security issues, and the legal liability that they create for business owners if they are not adequately addressed during the hiring process, outweigh the job applicant’s expectation of privacy when it comes to their social media activities.

Speaking of which, I can still hear people screaming (actually tweeting and retweeting) that an employer asking for your Facebook password is a horrible invasion of privacy. Well, for those of you who still believe in Santa Claus, I strongly recommend that you read The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You by Eli Pariser (Penguin Press). Or you can just take my advice and let go of the illusion of privacy on social media. The courts are conflicted, at best, on whether we as social media users have a right to an expectation of privacy, with many cases being decided against such expectations. The last place you want to share anything that is truly private is on your Facebook page or any other social media platform. Better to think of social media as the ultimate “Front Street.” No matter what Facebook’s privacy policies are (which they can change at will without your permission) and what privacy tools and settings they offer (which they also change whenever it suits their business models), always assume that posting on Facebook is just the ticking time bomb version of you shouting your private business from the middle of Times Square — on steroids.

To paraphrase a quote shared in The Filter Bubble, if you’re getting something for free, you’re not the customer, you’re the product. Social media is designed for the information shared on it to be searched and shared — and mined for profit. The business model is the very antithesis of the expectation of privacy. To ignore that reality is to have blind faith in Facebook, Google, Twitter, etc., operating in your best interests above all else, at all times. (I don’t.)

Whether you agree with me or not about whether a potential employer asking you for your Facebook password is fair game, I hope you’ll take my advice: When considering what to share via social media, don’t think business vs. personal. Think public vs. private. And if something is truly private, do not share it on social media out of a misplaced faith in the expectation of privacy.

This debate is far from over, and efforts to update existing, but woefully outdated, privacy laws — not to mention the hiring practices of companies — to catch up with the realities of social media will definitely continue. I’d like to know where you stand, both as entrepreneurs and business owners, as well as potential job applicants. And I’d especially like to hear from human resources and recruiting experts. How far is too far when it comes to a potential employer investigating the social media activity of a job applicant?

Topics for Critical Thinking and Writing

Employers do (at least at the time we’re writing this textbook) have the right to require drug tests and personality tests. Do you think they should also legally be allowed to ask for a password to Facebook, or should Congress pass legislation outlawing the practice? If employers are legally allowed to ask, would you provide your password? Why, or why not?

Would Alfred Edmond Jr.’s case be strengthened if he gave one or two additional examples — beyond the “child care industry” that he mentions in paragraph 5 — of jobs that, a reader might agree, require a thorough background check? What examples can you suggest? Would you say that applicants for these jobs should be willing to reveal their Facebook password to a potential employer? Why, or why not?

In paragraph 7, Edmond paraphrases: “if you’re getting something for free, you’re not the customer, you’re the product.” Paraphrase this passage yourself (on paraphrase, see Summarizing and Paraphrasing) so that it would be clear to a reader who finds it puzzling.