Instructor Notes

See the Additional Resources for Topics for Critical Thinking and Writing and reading comprehension quizzes for this chapter.

4

Visual Rhetoric: Thinking about Images as Arguments

A picture is worth a thousand words.

— PROVERB

“What is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversations?”

— LEWIS CARROLL

Uses of Visual Images

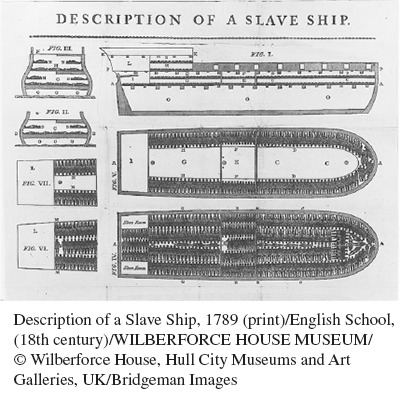

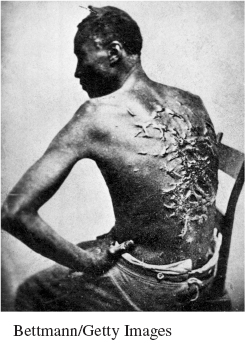

Most visual materials that accompany written arguments serve one of several functions. One of the most common is to appeal to the reader’s emotions (e.g., a photograph of a sad-eyed calf in a narrow pen can assist an argument against eating meat by inspiring sympathy for the animal). Pictures can also serve as visual evidence, offering proof that something occurred or appeared in a certain way at a certain moment. Pictures can help clarify numerical data (e.g., a graph showing five decades of law school enrollment by males and females). They can also add humor or satire to an essay. In this chapter, we concentrate on thinking critically about visual images. This means reading images in the same way we read print (or electronic) texts: by looking closely at them and discerning not only what they show but also how and why they convey a particular message, or argument.

When we discussed the appeal to emotion in Chapter 3, we quoted from Marc Antony’s speech to the Roman populace in Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar. You’ll recall that Antony stirred the mob by displaying Caesar’s blood-stained mantle. He wasn’t holding up a picture, but in a similar way he supplemented his words with visual material:

Look, in this place ran Cassius’ dagger through;

See what a rent the envious Casca made;

Through this, the well-belovèd Brutus stabbed. . . .

In courtrooms today, trial lawyers and prosecutors accomplish the same thing when doing the following:

exhibiting photos of a bloody corpse, or

holding up a murder weapon for jurors to see, or

introducing victims as witnesses who sob while describing their ordeal.

Lawyers know that such visuals help make good arguments. Whether presented sincerely or gratuitously, visuals can have a significantly persuasive effect. Such appeals to emotion work on feelings, not logic. Think about the suit and tie that lawyers advise their male clients to wear: The attire helps make an argument to the jury about the defendant’s character or credibility, even if he is actually lacking these qualities. Images, too, may be rationally connected to an argument (e.g., a gruesome image of a diseased lung in an anti-smoking ad makes a reasonable claim), but their immediate impact is more on the viewer’s heart than the mind.

Like any kind of evidence, images make statements and support arguments. When Congress debated over whether to allow drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), both opponents and supporters made use of images:

Opponents of drilling showed beautiful pictures of polar bears frolicking, wildflowers in bloom, and caribou on the move.

Proponents of drilling showed bleak pictures of what they called “barren land” and “a frozen wasteland.”

Both sides knew very well that images are powerfully persuasive, and they didn’t hesitate to use them as supplements to words.

We invite you to think about the appropriateness of using such images in arguments. Was either side manipulating the “reality” of the ANWR? Or do images such as those described provide reasonable support for the ideas under consideration? Should argument be entirely a matter of reason, of logic (logos), without appeals to the emotions (pathos)? A statement that “the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is a home for abundant wildlife, notably polar bears, caribou, and wildflowers” may not mean much until it is reinforced with breathtakingly beautiful images. Similarly, a statement that “most of the ANWR land is barren” may not mean much until it is corroborated by images of the vast bleakness. Each side selected a particular kind of image for a specific purpose — to support its position on drilling in the ANWR. Neither side was being dishonest, but both were appealing to emotions.

TYPES OF EMOTIONAL APPEALS

We began the preceding chapter by distinguishing between argument, which relies on reason (logos), and persuasion, which is a broad term that can include appeals to the emotions (pathos) — for example, an appeal to pity, such as an image of a sad-eyed calf. You might say, “Well, eating meat implies confining and killing animals,” and regard the image as both reasonable and emotionally powerful. Or you might say, “Although it’s emotionally powerful, this appeal to pity doesn’t describe the condition of every meat animal. Some are treated humanely, slaughtered humanely, and eaten ethically.” You might write a counterargument and include an image of free-range cattle on a farm (although in doing this, you too would be appealing to emotions).

The point is that images can be persuasive even if they don’t make good arguments, in the same way threats of violence can be persuasive but do not make good arguments. The gangster Al Capone famously said, “You can get a lot more done with a kind word and a gun than with a kind word alone.” Threats of violence appeal exclusively to the emotions — specifically, fear.

Advertisers commonly use the appeal to fear as a persuasive technique. While it is not a threat of violence, the appeal to fear is a threat of sorts. Showing a burglary, a car crash, embarrassing age spots, or a cockroach infestation can successfully convince consumers to buy a product — a home security system, a new car insurance policy, an age-defying skin cream, or a pesticide. Such images generate fear and anxiety at the same time that they offer the solution for it.

Appeal to self-interest is another persuasive tactic that writers can use. Consider these remarks, which use the word interest in the sense of “self-interest”:

Would you persuade, speak of Interest, not Reason. — BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

There are two levers for moving men — interest and fear. — NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

Appeals to self-interest may be quite persuasive because they speak directly to what benefits you the most, not necessarily what benefits others in the community, society, or world. Such appeals are also common in advertising. “You can save bundles by shopping at Maxi-Mart,” a commercial might claim, without making reference to sweatshop labor conditions, the negative impact of global commerce, or other troublesome aspects of what you see only as a great savings for yourself. You may be familiar with other types of emotional appeals in advertising that speak to the senses more than to the rational mind. Again, these kinds of appeals don’t necessarily make good arguments for the products in question, but each can be highly persuasive — sometimes affecting us subconsciously. (The same applies to appeals in written arguments. This is why thinking critically about both words and images is so important.)

Here is a list of some additional kinds of appeals to emotion:

Sexual appeals (Example: showing a bikini-clad model standing near a product)

Bandwagon appeals (Example: showing crowds of people rushing to a sale)

Humor appeals (Example: showing a cartoon animal drinking X brand of beverage)

Celebrity appeals (Example: showing a famous person driving X brand of car)

Testimonial appeals (Example: showing a doctor giving X brand of vitamins to her kids)

Identity appeals (Example: showing a “good family” going to X restaurant)

Prejudice appeals (Example: showing a “loser” drinking X brand of beer)

Lifestyle appeals (Example: showing a jar of X brand of mustard on a silver platter)

Stereotype appeals (Example: showing a Latino person enjoying X brand of salsa)

Patriotic appeals (Example: showing X brand of mattress alongside an American flag)

Exercise

Watch the commercials that air during a television show, or examine the print advertisements in a popular magazine. Identify as many examples as possible of the types of appeals mentioned mentioned above. Is there a rational basis for any of the appeals you see? Are any appeals irrational even if they are effective? Why, or why not?