Writing about a Political Cartoon

Most editorial pages print political cartoons as well as editorials. Like the writers of editorials, cartoonists seek to persuade, but they rarely use words to argue a point. True, they may use a few words in speech balloons or in captions, but generally the drawing does most of the work. Because their aim usually is to convince the viewer that some person’s action or proposal is ridiculous, cartoonists almost always caricature their subjects:

They exaggerate the subject’s distinctive features to the point at which . . .

. . . the subject becomes grotesque and ridiculous — absurd, laughable, contemptible.

We agree that it’s unfair to suggest that because, say, the politician who proposes such-and-such is short, fat, and bald, his proposal is ridiculous; but that’s the way cartoonists work. Further, cartoonists are concerned with producing a striking image, not with exploring an issue, so they almost always oversimplify, implying that there really is no other sane view.

In the course of saying that (1) the figures in a cartoon are ridiculous and therefore their ideas are contemptible, and (2) there is only one side to the issue, cartoonists often use symbolism. Here’s a list of common symbols:

symbolic figures (e.g., the U.S. government as Uncle Sam)

animals (e.g., the Democratic Party as donkey and the Republican Party as elephant)

buildings (e.g., the White House as representing the nation’s president)

things (e.g., a bag with a dollar sign on it as representing a bribe)

For anyone brought up in U.S. culture, these symbols (like the human figures they represent) are obvious, and cartoonists assume that viewers will instantly recognize the symbols and figures, will get the joke, and will see the absurdity of whatever issue the cartoonist is seeking to demolish.

In writing about the argument presented in a cartoon, normally you will discuss the ways in which the cartoon makes its point. Caricature usually implies, “This is ridiculous, as you can plainly see by the absurdity of the figures depicted” or “What X’s proposal adds up to, despite its apparent complexity, is nothing more than. . . .” As we have said, this sort of persuasion, chiefly by ridicule, probably is unfair: An unattractive person certainly can offer a thoughtful political proposal, and almost always the issue is more complicated than the cartoonist indicates. But cartoons work largely by ridicule and the omission of counterarguments, and we shouldn’t reject the possibility that the cartoonist has indeed highlighted the absurdity of the issue.

A CHECKLIST FOR EVALUATING AN ANALYSIS OF POLITICAL CARTOONS

Is there a lead-in?

Is there a brief but accurate description of the drawing?

Is the source of the cartoon cited (perhaps with a comment by the cartoonist)?

Is there a brief report of the event or issue that the cartoon is targeting, as well as an explanation of all the symbols?

Is there a statement of the cartoonist’s claim (thesis)?

Is there an analysis of the evidence, if any, that the image offers in support of the claim?

Is there an analysis of the ways in which the drawing’s content and style help to convey the message?

Is there adequate evaluation of the drawing’s effectiveness?

Is there adequate evaluation of the effectiveness of the text (caption or speech balloons) and of the fairness of the cartoon?

Your essay will likely include an evaluation of the cartoon. Indeed, the thesis underlying your analytic/argumentative essay may be that the cartoon is effective (persuasive) for such-and-such reasons but unfair for such-and-such other reasons.

In analyzing the cartoon — in determining the cartoonist’s attitude — consider the following elements:

the relative size of the figures in the image

the quality of the lines (e.g., thin and spidery, or thick and seemingly aggressive)

the amount of empty space in comparison with the amount of heavily inked space (a drawing with lots of inky areas conveys a more oppressive tone than a drawing that’s largely open)

the degree to which text is important, as well as its content and tone (is it witty, heavy-handed, or something else?)

Caution: If your instructor lets you choose a cartoon, be sure to select one with sufficient complexity to make the exercise worthwhile. (See also Thinking Critically: Analysis of a Political Cartoon.)

Let’s look at an example. Jackson Smith wrote this essay in a composition course at Tufts University.

THINKING CRITICALLY Analysis of a Political Cartoon

Look at the cartoon above. For each Type of Analysis section in the chart below, provide your own answer based on the cartoon. (Sample answers appear in the third column.)

| TYPE OF ANALYSIS | QUESTIONS TO ASK | SAMPLE ANSWER | YOUR ANSWER |

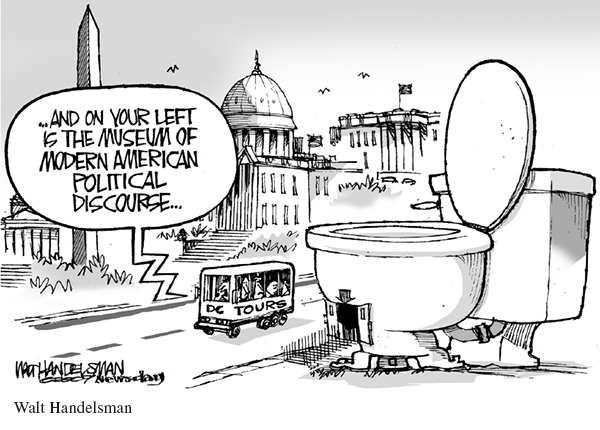

| Context | Who is the artist? Where and when was the cartoon published? | “This cartoon by Walt Handelsman was originally published in Newsday on September 12, 2009. Handelsman, a Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist, drew this cartoon in response to recent breaches of political decorum.” | |

| Description | What does the cartoon look like? | “It depicts a group of Washington, D.C., tourists being driven past what the guide calls ‘The Museum of Modern American Political Discourse,’ a building in the shape of a giant toilet.” | |

| Analysis | How does the cartoon make its point? Is it effective? | “The toilet as a symbol of the level of political discussion dominates the cartoon, effectively driving home the point that Americans are watching our leaders sink to new lows as they debate the future of our nation. By drawing the toilet on a scale similar to that of familiar monuments in Washington, Handelsman may be pointing out that today’s politicians, rather than being remembered for great achievements like those of George Washington or Abraham Lincoln, will instead be remembered for their rudeness and aggression.” |

To complete this activity online, click here.

To complete this activity online, click here.