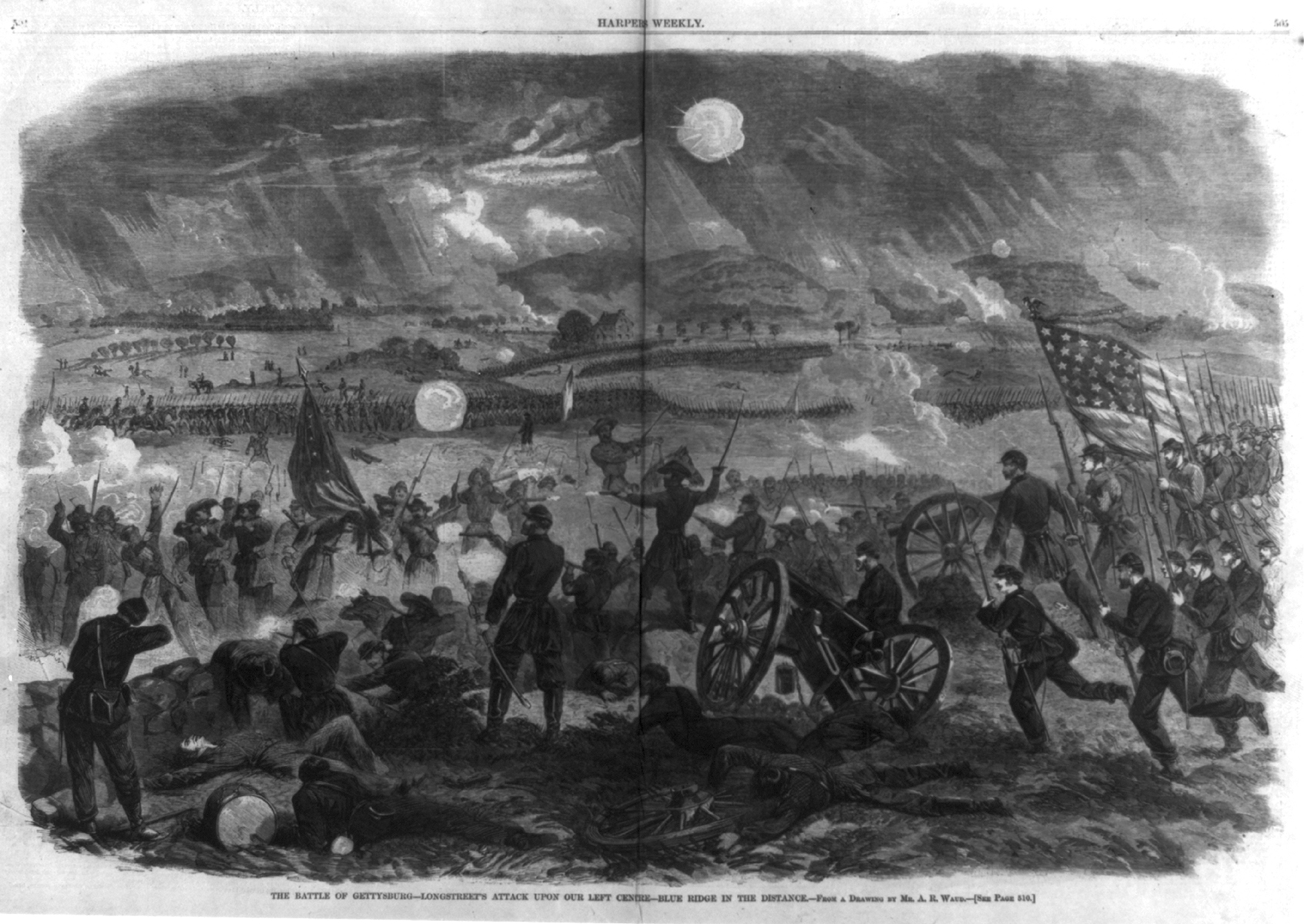

“The Battle of Gettysburg — Longstreet’s Attack,” Harper’s Weekly, August 1863

Illustrated magazines like Harper’s Weekly dispatched artists to watch battles and sketch them as they unfolded. Later, a different team of artists turned those sketches into engravings for publication, often embellishing the drawings they received from the front. These artistic representations were bound by a set of restraints. Artists could sketch only what they could see and could not venture further forward than the fighting would allow. Sight lines were compromised by dips and swells in the terrain and by the weapons technology of the day — the black powder used in the Civil War produced a thick, heavy smoke that obscured large parts of the battlefield from view. And depicting a terrifying, noisy, confusing event like a battle in a black-and-white still drawing tested the skills of even the most talented and brave artist.

This engraving of a Confederate attack led by General James Longstreet appeared the month after the battle and was based on sketches produced by Arthur Waud, who won a reputation as one of the most intrepid artists of the war by following the Union’s Army of the Potomac in all its campaigns from Antietam in 1862 to the Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in April 1865.

Evaluating the Evidence

Question

bg3IqT0EBVwsalmVPuZOM4UDZJJkGJmOONStS9ZuC9yfV9Gko11F0Lo1W4f8AqJi7HbxgV2g7e8VGnu8/NtGLLPzN3YEissGGRAlXP3fXdVAxW7sT3jEBvzxoQ5tqV027woYaujRcF4zCqQmOzTftikk+rQPqxYn52flPuMETTWR+sxWMiqgDRLrdPoJyokqJj9WanLWSoDSZMS1eYaGiSE1YHe9oJs4lJawwXzwRNxbhzBeRurFMzl8a0I=Question

kdYYw424Rx5PzQWg7/4PVYIminLItUpzW90Ree0yP01XU9lwzhboAdBEokr/c3rx4ImYj6oJynXwKAIKaPTHznWL07qkA2kM5Jw9+cvFcOh0xc7wnol6anlN74frkfx9O3BP8aMmC6RlHH9sBlVz97syH+zqUiko3udfDQIX7Iwyt/bd35LqsYCfoMtS9klYCfvD7EwF34EW3gMmuxyIHb41yqmBDaPAeDjbzroW9UYZr7jB8kcWaInYHQ/gf5kNwhU/Y6LQFAyxow5vpGCb0s5YCtZmmD96R7leykXEwrBdUPz93tkwKUX1gqODJ7yMd1RecA==