Historical Background

Timeline

| 1756 | Seven Years’ War begins. |

| 1758 | The French destroy and abandon Fort Duquesne; the British soon replace it with Fort Pitt. |

| 1760 | Surrender of Montreal to British forces. |

| February 1763 | The Treaty of Paris signed, ending Seven Years’ War. |

| May 1763 | Pontiac initiates the attack on Detroit. |

| June 1763 | Ojibwe warriors capture Fort Michilimackinac; nine forts are captured by Native Americans and two besieged. |

| October 1763 | Royal Proclamation is issued. |

| 1764 | Colonel John Bradstreet marches on Detroit and negotiates a treaty there; Colonel Henry Bouquet advances to the Muskingum River. |

| 1765 | British troops occupy Fort Chartres, at the western end of the Ohio Valley, for the first time; Stamp Act is passed imposing new tax on American colonists. |

| 1766 | Pontiac signs a formal treaty ending the war; no land is ceded to Great Britain and no concessions are made. |

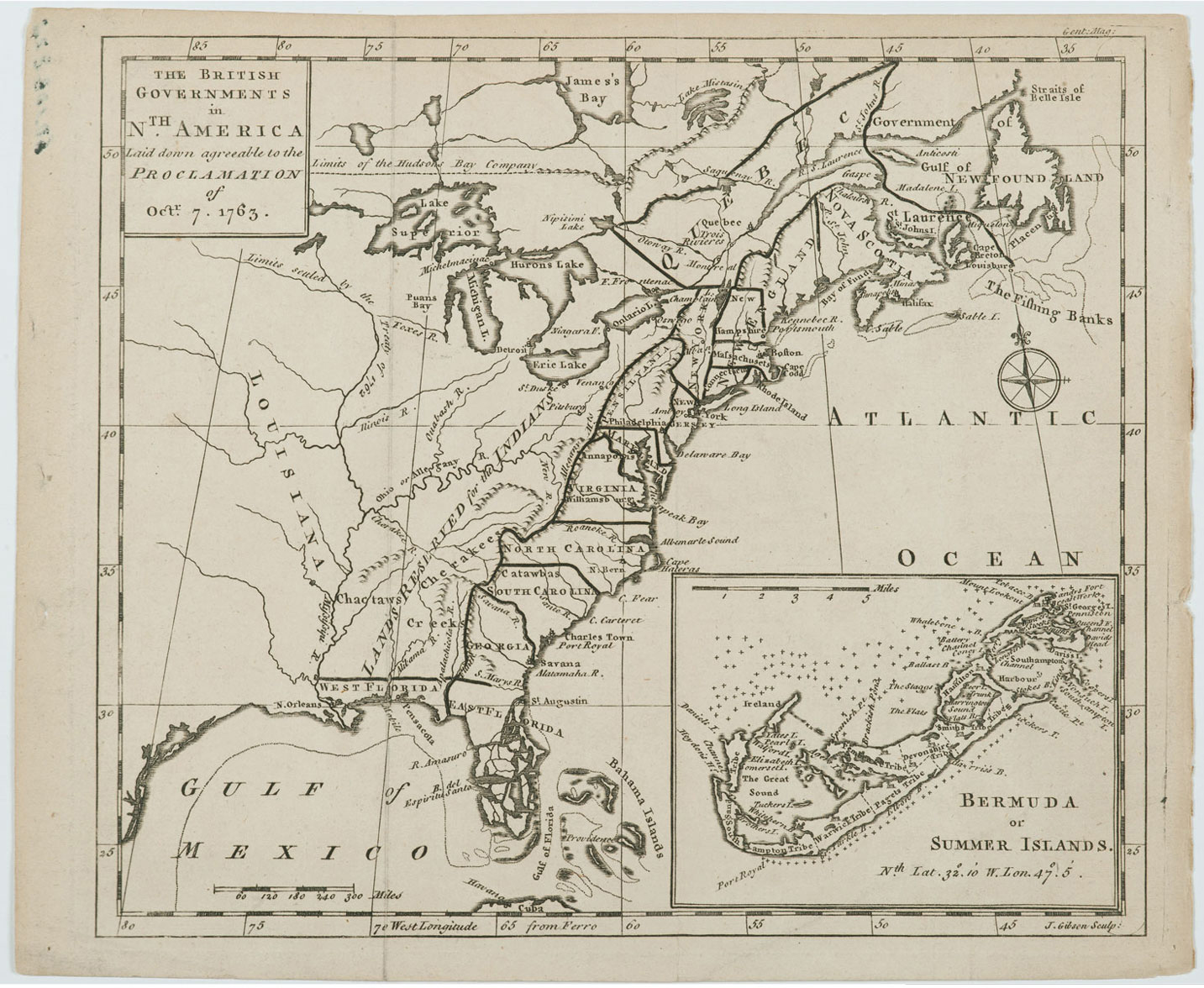

In September 1760, French Canada fell to British forces, thus ending the Seven Years’ War in North America. Two and a half years later, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, France and Spain ceded all claims to North America east of the Mississippi to Britain. This agreement significantly shifted the balance of power on the eastern half of the continent. Many Native American polities of the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley had maintained diplomatic relations with New France for generations, and Britain’s takeover of the trans-Appalachian West threatened their autonomy and interests. When news of the agreement of the Treaty of Paris reached Native American communities in the region it triggered a war against Great Britain.

Native American grievances began with the simple fact that Indians had not been defeated in the war, nor were they parties to the Treaty of Paris. Prior to its defeat, France occupied a network of forts and trading posts in the region with the permission of local Native American leaders. British colonists, on the other hand, had the reputation of flocking to new fort sites and displacing Indian populations. British General Jeffery Amherst, moreover, began to cut off diplomatic presents and restrict trade with Indians. Famine and epidemic disease were affecting some native towns, and Amherst’s new restrictions made matters only worse.

With the relationship between Native Americans and the British deteriorating, some native leaders decided to take more active measures. In May 1763, an Ottawa ogema (civil leader) named Pontiac tried to capture Fort Detroit, a formerly French outpost in British hands. Although this attempt failed, Pontiac led a force that besieged Fort Detroit throughout the summer. Inspired by that example, native warriors attacked every British-controlled fort in the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley, beginning Pontiac’s war. As a result, the British lost control of nine forts, while two others were subjected to prolonged sieges. Nearly three hundred British troops were killed in the attacks, along with several hundred colonists; thousands more were displaced. The British army mounted a campaign to recapture the lost forts in 1764, but it did not occupy the last French fort in the Ohio Valley until October 1765. This war taught crown officials that Native Americans in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley were a formidable force, their claims to territory and autonomy not to be taken lightly. As a result of Pontiac’s war, the crown issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which sought to protect Indian land claims and required Indian traders to be licensed. First Nations peoples of Canada still ground their claims to territorial rights under the crown in this landmark document.

Historians once called this war a “conspiracy” or an “uprising” and regarded Pontiac as an especially powerful leader. However, modern scholars now see Pontiac as one local leader among many; they reject the terms conspiracy and uprising because they imply the legitimacy of British authority in the region.