Historical Background

Timeline

| 1846–1848 | Mexican-American War. |

| 1848 | Zachary Taylor elected president. |

| Gold discovered in California. | |

| July 9, 1850 | Taylor dies; Millard Fillmore succeeds him. |

| 1850 | Compromise of 1850. |

| 1852 | Publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. |

| Franklin Pierce elected president. | |

| 1854 | Kansas-Nebraska Act. |

| 1855–1856 | Bleeding Kansas. |

| May 22, 1856 | Bleeding Sumner. |

| 1856 | James Buchanan elected president. |

| 1857 | Dred Scott decision. |

| Lecompton Constitution. | |

| 1858 | Freeport Doctrine/Lincoln-Douglas debates. |

| October 16–18, 1859 | John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. |

| November 6, 1860 | Abraham Lincoln elected president. |

| December 20, 1860 | South Carolina secedes; Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas depart by February 1, 1861. |

| March 4, 1861 | Lincoln sworn into office. |

| April 12–13, 1861 | Firing on Fort Sumter. |

| April 17, 1861 | Virginia secedes, followed by Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee. |

| July 21, 1861 | First Bull Run, the first major battle of the Civil War. |

| September 17, 1862 | Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day in U.S. history. |

| September 22, 1862 | Lincoln issues the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation; final version goes into effect January 1, 1863. |

| July 1–3, 1863 | Battle of Gettysburg. |

| July 4, 1863 | Vicksburg falls, giving the Union full control of the Mississippi River. |

| April 9, 1865 | General Robert E. Lee surrenders. |

| April 14, 1865 | Lincoln assassinated. |

The Mexican-American War, which ended in 1848, added half a million square miles of new territory to the United States and prompted a renewed, and increasingly vitriolic, argument over the expansion of slavery. At stake was not only the future of the peculiar institution, as it was called, but also the nature of the country itself. As the nation wrestled with this question, a series of events took place over the 1850s that set the United States hurdling toward disunion. These events seemed to snowball, coming ever faster at Americans, North and South. The key episodes of the decade included the following.

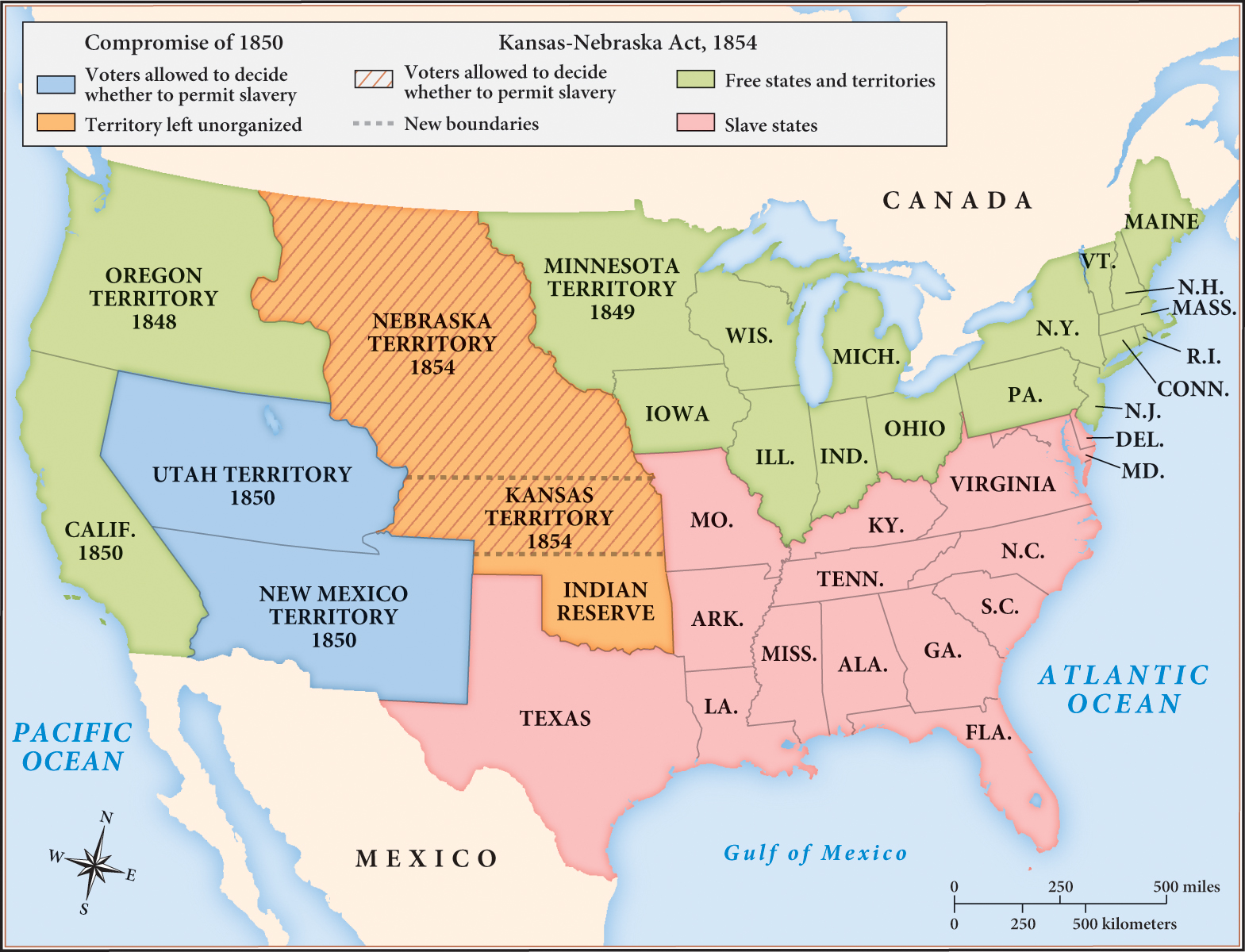

Compromise of 1850. This included a provision that required Northerners to pursue and capture runaway slaves, even when slavery was illegal in their states. To many people in the North, this belied Southerners’ claims that states’ rights trumped all. Instead, Southerners seemed to invoke states’ rights only when it protected their own interests.

Publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). This antislavery novel was a runaway best seller. At a time when the idea of family held great romantic appeal, a story of families being divided and their members being sold convinced many Northerners that slavery was an evil institution.

Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854). Written and promoted by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, this law allowed residents to decide themselves (“popular sovereignty”) whether slavery would be legal in their two territories. The question was not relevant in Nebraska, but Kansas sat just west of Missouri, a slave state, and eastern Kansas and western Missouri shared a similar climate. Missourians were worried that if Kansas were a free territory it would be surrounded on three sides by states or territories in which slavery was illegal — an inducement for Missouri slaves to run away.

Bleeding Kansas (1855–1856). Missourians regularly crossed the border and cast fraudulent votes to elect a proslavery Kansas legislature. Abolitionists in the East subsidized antislavery settlers to move into Kansas to help offset the actions of the “border ruffians.” Violence soon broke out in eastern Kansas. The hub of abolitionist activities, Lawrence, was sacked on May 21, 1856, prompting John Brown to go on a rampage on the nights of May 24–25 along Pottawatomie Creek, Kansas; he and his followers killed five proslavery settlers.

Bleeding Sumner (May 22, 1856). Charles Sumner, an abolition senator from Massachusetts, mocked a South Carolina senator as loving “the harlot, Slavery.” Believing his family’s honor had been besmirched, the South Carolinian’s cousin, Representative Preston Brooks, came from the House to the Senate floor and beat Sumner nearly to death with a cane. His knees trapped beneath his desk, Sumner could not escape and was so badly injured that he would not return to work for three years. Brooks resigned his seat but was reelected. Many people in the North were horrified at this assault, but Southerners cheered the attack and sent Brooks canes as tokens of their support.

Dred Scott decision (1857). This U.S. Supreme Court ruling held that Dred Scott, a slave who had spent a number of years with his master in free states, could not be freed. More important, Chief Justice Roger Taney, a former slave owner from Maryland, ruled that African Americans, free or slave, were not citizens of the United States and had no rights, and that Congress had no right to ban slavery in the territories. This made many people in the North wonder whether the next case regarding slavery would make the institution legal across the country. Historians consider this ruling to be one of the worst in the history of the Supreme Court.

Lecompton Constitution (1857). Kansas made national news again when proslavery advocates presented voters with two choices for their new state constitution. The “constitution with slavery” allowed slavery and protected the rights of slave owners. The “constitution without slavery” also protected slavery in that slaves already in the territory would continue to be enslaved; no new slaves would be allowed, however — a commitment that would be difficult to enforce. Antislavery settlers boycotted the vote, and President James Buchanan recognized the constitution with slavery — the Lecompton Constitution.

Freeport Doctrine (1858). During the Lincoln-Douglas debate in Freeport, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln pressed the sitting senator, Stephen A. Douglas, to defend the consequences of his popular sovereignty policy. Douglas squirmed and said that if they did not want slavery, the residents of a territory could refuse to enact laws that would support the institution. The comment set off a firestorm within the Democratic Party and ultimately cost Douglas the support of Southerners in the 1860 election.

Raid on Harper’s Ferry (October 16–18, 1859). John Brown made another dramatic appearance on the national stage when he and a small band of followers raided Harper’s Ferry, Virginia (now part of West Virginia), taking control of the town and, more important, its federal arsenal. Brown expected his actions to prompt a slave uprising that would terrify Virginians before Brown, a committed abolitionist, moved farther south. Groups of slaves never joined him, though, and Brown and his followers succumbed in short order when a detachment of Marines, led by Army Colonel Robert E. Lee, arrived on the scene. Ten of Brown’s men were killed at Harper’s Ferry, eight — including Brown — were captured, and five others escaped. Brown was hanged December 2. For Southerners, Brown’s plot confirmed their worst suspicions about abolitionists in particular and Northerners in general: that they wanted to incite slave revolts that would result in the deaths of many white owners and their families.

Abraham Lincoln’s election (November 6, 1860). Abraham Lincoln said that he wanted to stop slavery’s expansion into the territories but would not touch it in the states where it already existed and was constitutionally protected. Southerners did not believe him. Lincoln represented the Republican Party, which had been founded in 1854 as an explicitly antislavery party (antislavery being a more moderate approach than abolitionism, which demanded an immediate end to the institution everywhere). Lincoln did not receive a single electoral vote from a southern state.

The Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854