Generating Ideas

Identify a Problem. Brainstorm by writing down all the topics that come to mind. Observe events around you to identify irritating campus or community problems you would like to solve. Watch for ideas in the news. Browse through issue-oriented Web sites. Look for sites sponsored by large nonprofit foundations that accept grant proposals and fund innovative solutions to societal issues. Although a controversy or current issue might start you thinking, be sure to stick to problems that you want to solve as you consider options. Star the ideas that seem to have the most potential.

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

- Can you recall any problem that needs a solution? What problems do you meet every day or occasionally? What problems concern people near you?

- What conditions in need of improvement have you observed on television, on the Web, or in your daily activities? What action is called for?

- What problems have been discussed recently on campus or in class?

- What problems are discussed in blogs, online or print newspapers, or newsmagazines such as Time, The Week, or U.S. News & World Report?

Consider Your Audience. Readers need to believe that your problem is real and your solution is feasible. If you are addressing classmates, maybe they haven’t thought about the problem before. Look for ways to make it personal for them, to show that it affects them and deserves their attention.

- Who are your readers? How would you describe them?

- Why should your readers care about this problem? Does it affect their health, welfare, conscience, or pocketbook?

- Have they ever expressed any interest in the problem? If so, what has triggered their interest?

- Do they belong to any organization or segment of society that makes them especially susceptible to — or uninterested in — this problem?

- What attitudes about the problem do you share with your readers? Which of their assumptions or values that differ from yours will affect how they view your proposal?

Think about Solutions. Once you’ve chosen a problem, brainstorm — alone or with classmates — for possible solutions, or use your imagination. Some problems, such as reducing international tensions, present no easy solutions. Still, give some strategic thought to any problem that seriously concerns you, even if it has stumped experts. Sometimes a solution reveals itself to a novice thinker, and even a partial solution is worth offering.

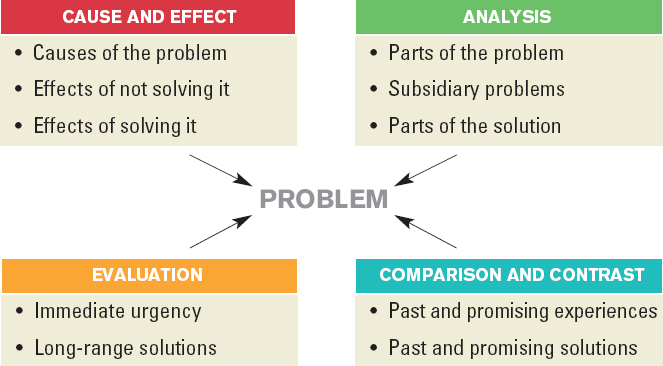

See more on causes and effects, see Ch. 8 and pp. 455–57. For more on analysis.

For more on comparison and contrast, see Ch. 7. For more on evaluation, see Ch. 11.

See more on evidence, see Ch. 3. For more on using evidence to support an argument.

Consider Sources of Support. To show that the problem really exists, you’ll need evidence and examples. If further library research will help you justify the problem, now is the time to do it. Consider whether local history archives, newspaper stories, accounts of public meetings, interviews, or relevant Web sites might identify concerns of readers, practical limits of solutions, or previous efforts that help you develop your solution.