Generating Ideas

For more strategies for generating ideas, see Ch. 19.

Pin Down Your Working Topic and Your Cluster of Readings. Specify what you’re going to work on. This task is relatively easy if your instructor has assigned the topic and the required set of readings. If not, figure out what limits your instructor has set and which decisions are yours.

- Carefully follow any directions about the number or types of sources that you are expected to use.

- Instead of hunting only for sources that share your initial views about the topic, look for a variety of reliable and relevant sources so that you can broaden, even challenge, your perspective.

See sections B and C in the Quick Research Guide for advice about finding and evaluating academic sources.

Consider Your Audience. You are writing for an academic community that is intrigued by your topic (unless your instructor specifies another group). Your instructor’s broad goal probably includes making sure that you are prepared to succeed when you write future assignments, including full research papers. For this reason, you’ll be expected to quote, paraphrase, and summarize information from sources. You’ll also need to introduce — or launch — such material and credit its source, thus demonstrating that you have mastered the essential skills for source-based writing.

In addition, your instructor will want to see your own position emerge from the swamp of information that you are reading. You may feel that your ideas are like a prehistoric creature, dripping as it struggles out of the bog. If so, encourage your creature to wade toward dry land. Jot down your own ideas whenever they pop into mind. Highlight them in color on the page or on the screen. Store them in your writing notebook or a special file so that you can find them, watch them accumulate, and give them well-deserved prominence in your paper.

For clusters of readings on this topic and others, see the contents of A Writer’s Reader.

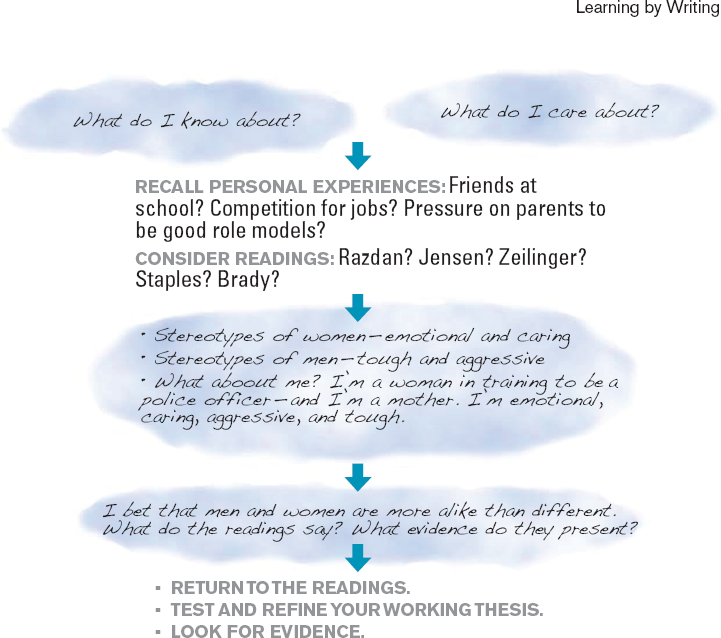

One Student Thinking through a Topic

General Subject: Men and Women

Assigned topic: State and support a position about differences in the behavior of men and women.

For more on generating ideas, see Ch. 19.

Take an Academic Approach. Your experience and imagination remain your own deep well, an endless reservoir from which you can draw ideas whenever you need them. For an academic paper, this deep well may help you identify an intriguing topic, raise a compelling question about it, or pursue an unusual slant. For example, you might recall talking with your cousin about her expensive prescriptions and decide to investigate the controversy about importing low-cost medications from other countries.

For more on reading critically, see Ch. 2.

To see how the academic exchange works, turn to pp. 238–39.

You’ll also be expected to investigate your topic using authoritative sources. These sources — articles, essays, reports, books, Web pages, and other reliable materials — are your second deep well. When one well runs dry for the moment, start pumping the other. As you read critically to tap your second reservoir, you join the academic exchange. This exchange is the flow of knowledge from one credible source to the next as writers and researchers raise questions, seek answers, evaluate information, and advance knowledge. As you inquire, you’ll move from what you already know to deeper knowledge. Welcome sources that shed light on your inquiry from varied perspectives rather than simply agree with a view you already hold.

Skim Your Sources. When you work with a cluster of readings, you’ll probably need to read them repeatedly. Start out, however, by skimming — quickly reading only enough to find out what direction a selection takes.

- Leaf through the reading; glance at any headings or figure labels.

- Return to the first paragraph; read it in full. Then read only the first sentence of each paragraph. At the end, read the final paragraph in full.

- Stop to consider what you’ve already learned.

Do the same with your other selections, classifying or comparing them as you begin to think about what they might contribute to your paper.

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

See more on stating a thesis.

- What topic is assigned or under consideration? What ideas about it emerge as you brainstorm, freewrite, or use another strategy to generate ideas?

- What cluster of readings will you begin with? What do you already know about them? What have you learned about them simply by skimming?

- What purpose would you like to achieve in your paper? Who is your primary audience? What will your instructor expect you to accomplish?

- What clues about how to proceed can you draw from the two sample essays in this chapter or from other readings identified as useful models?