E. Designing Other Documents for Your Audience

Four key principles of document design can help you prepare effective documents in and out of the classroom: know your audience, satisfy them with the features and format they expect, consider their circumstances, and remember your purpose.

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

- Who are your readers? What matters to them? How might the format of your document acknowledge their values, goals, and concerns?

- What form or genre do readers expect? Which of its features and details do they see as typical? What visual evidence would they find appropriate?

- What problems or constraints will your readers face as they read your document? How can your design help to reduce these problems?

- What is the purpose of your document? How can its format help achieve this purpose? How might it enhance your credibility as a writer?

- What is the usual format of your document? Find and analyze a sample.

| E1 | Select type font, size, and face |

Typography refers to the appearance of letters on a page. You can change typeface or font, style from roman to bold or italics, or type size for a passage by highlighting it and clicking on the appropriate toolbar icon. Selecting Font in the Home, Format, or Page Layout menu usually leads to options such as superscript, shadows, or small capitals.

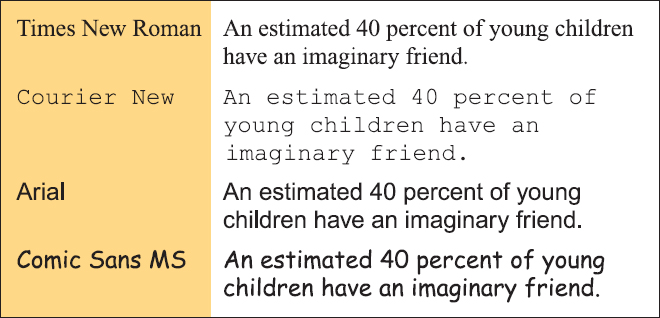

Most college papers and many other documents use Times New Roman in a 12-point size. Signs, posters, and visuals such as slides for presentations might require larger type (with a larger number for the point size). Test such materials for readability by printing samples in various type sizes and standing back from them at the distance of your intended audience. Size also varies with different typefaces because they occupy different amounts of horizontal space on the page. Figure A.5 shows the space required for the same sentence written in four different 12-point fonts.

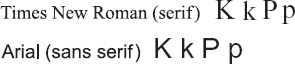

Fonts also vary in design. Times New Roman and Courier New are called serif fonts because they have small tails, or serifs, at the ends of the letters. Arial and the more casual Comic Sans MS are sans serif — without serifs — and thus have solid, straight lines without tails at the tips of the letters.

Sans serif fonts have a clean look, desirable for headlines, ads, “pull quotes” (in larger type to catch the reader’s eye), and text within APA-style figures. More readable serif fonts are used for article (or “body”) text. Times New Roman, the common word-processor default font preferred for MLA and APA styles, was developed for the Times newspaper in London. As needed, use light, slanted italics (for certain titles) or dark bold (for APA headings).

| E2 | Organize effective lists |

The placement of material on a page — its layout — can make information more accessible for readers. MLA style recognizes common ways of integrating a list within a sentence: introduce the list with a colon or dash (or set it off with two dashes); separate its items with commas, or use semicolons if the items include commas. APA style adds options, preceding each item in a sentence with a letter enclosed by parentheses: (a), (b), and (c) or using display lists — set off from text — for visibility and easy reading.

One type of displayed list, the numbered list, can emphasize priorities, conclusions, or processes such as steps in research procedures, how-to advice, or instructions, as in this simple sequence for making clothes:

NUMBERED LIST

- Lay out the pattern and fabric you have selected.

- Pin the pattern to the fabric, noting the arrows and grain lines.

- Cut out the fabric pieces, following the outline of the pattern.

- Sew the garment together using the pattern’s step-by-step instructions.

Another type of displayed list sets off a bit of information with a bullet, most commonly a small round mark ( • ) but sometimes a square ( ▪ ), from the Home or Symbol menu. Bulleted lists are common in résumés and business documents but not necessarily in academic papers, though APA style now recognizes them. Use them to identify steps, reasons, or items when you do not wish to suggest any order of priority, as in this list of tips for saving energy.

BULLETED LIST

- Let your hair dry without running a hair dryer.

- Commute by public transportation.

- Turn down the thermostat by a few degrees.

- Unplug your phone charger and TV during the day.

| E3 | Consider adding headings |

In a complex research report, business proposal, or Web document, headings can show readers how the document is structured, which sections are most important, and how parts are related. Headings also name sections so readers know where they are and where they are going. Headings at the same level should be consistent and look the same; headings at different levels should differ from each other and from the main text in placement and style, making the text easy to scan for key points.

For academic papers, MLA encourages writers to organize by outlining their essays but does not recommend or discuss text headings. In contrast, APA illustrates five levels of headings beginning with these two:

First-Level Heading Centered in Bold

Second-Level Heading on the Left in Bold

Besides looking the same, headings at the same level in your document should be brief, clear, and informative. They also should use consistent parallel phrasing. If you write a level-one heading as an -ing phrase, do the same for all the level-one headings that follow. Here are some examples of four common patterns for phrasing headings.

See section B2 in the Quick Editing Guide for more on parallel structure.

| -ING PHRASES | QUESTIONS |

| Using the College Catalog | What Is Hepatitis C? |

| Choosing Courses | Who Is at Risk? |

| Declaring a Major | How Is Hepatitis C Treated? |

| NOUN PHRASES | IMPERATIVE SENTENCES |

| E-Commerce Benefits | Initiate Your IRA Rollover |

| E-Commerce Challenges | Balance Your Account |

| Online Shopper Profiles | Select New Investments |

Web pages — especially home pages and site guides — are designed to help readers find information quickly, within a small viewing frame. For this reason, they generally have more headings than other documents. If you design a Web page or post your course portfolio, consider what different readers might want to find. Then design your headings and content to meet their needs.