A. Defining Your Quest

Especially when your research goals are specific and limited, you’re more likely to succeed if you try to define the hunt in advance.

PURPOSE CHECKLIST

See more about stating and using a thesis.

See more about types of evidence.

- What is the thesis you want to support, point you want to show, question you want to answer, or problem you want to solve?

- Does the assignment require or suggest certain types of supporting evidence, sources, or presentations of material?

- Which ideas do you want to support with good evidence?

- Which ideas might you want to check, clarify, or change?

- Which ideas or opinions of others do you want to verify or counter?

- Do you want to analyze material yourself (for example, comparing different articles or Web sites) or to find someone else’s analysis?

- What kinds of evidence do you want to use — facts, statistics, or expert testimony? Do you also want to add your own firsthand observation?

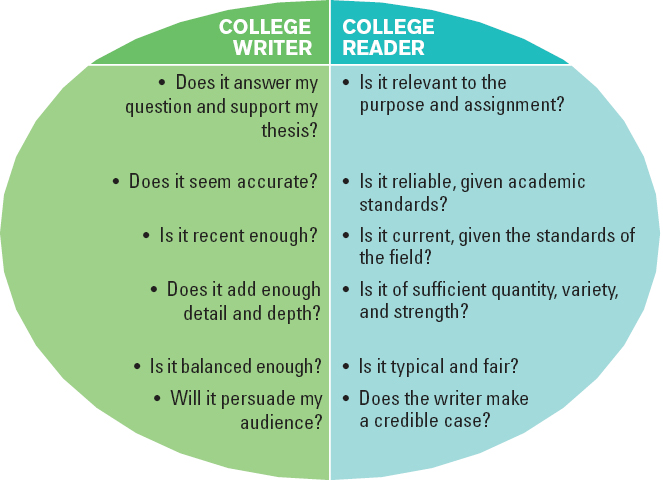

TWO VIEWS OF SUPPORTING EVIDENCE

See evidence checklists.

| A1 | Decide what supporting evidence you need |

When you want to add muscle to college papers, you need reliable resources to supply facts, statistics, and expert testimony to back up your claims. You may not need comprehensive information, but you will want to hunt — quickly and efficiently — for exactly what you do need. That evidence should satisfy you as a writer and meet the criteria of your college readers — instructors and possibly classmates. Suppose you want to propose solutions to your community’s employment problem.

WORKING THESIS

Many residents of Aurora need more — and more innovative — higher education to improve their job skills and career alternatives.

Because you already have ideas based on your firsthand observations and the experiences of people you know, your research goals are limited. First, you want to add accurate facts and figures that will show why you believe a compelling problem exists. Next, you want to visit the Web sites of local educational institutions and possibly locate someone to interview about existing career development programs.

| A2 | Decide where you need supporting evidence |

As you plan or draft, you may tuck in notes to yourself — figure that out, find this, look it up, get the numbers here. Other times, you may not know exactly what or where to add. One way to determine where you need supporting evidence is to examine your draft, sentence by sentence.

- What does each sentence claim or promise to a reader?

- Where do you provide supporting evidence to demonstrate the claim or fulfill the promise?

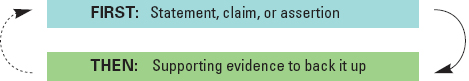

The answers to these questions — your statements and your supporting evidence — often fall into a common alternating pattern:

See more about arguments based on claims of substantiation, evaluation, or policy.

See more on inductive and deductive reasoning.

When you spot a string of assertions without much support, you have found a place where you might need more evidence. Select reliable evidence so that it substantiates the exact statement, claim, or assertion that precedes it. Likewise, if you spot a string of examples, details, facts, quotations, or other evidence, introduce or conclude it with an interpretive statement that explains the point the evidence supports. Make sure your general statement connects and pulls together all of the particular evidence.

See the source entries from Carrie Williamson’s MLA list of works cited.

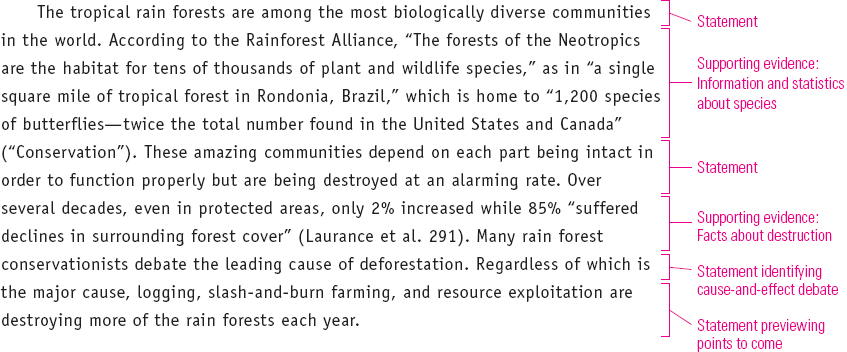

When Carrie Williamson introduced her cause-and-effect paper, “Rain Forest Destruction,” she made a general statement and then supported it by quoting facts from a source. Then she repeated this statement-support pattern, backing up her next statement in turn. By using this pattern from the very beginning, Carrie reassured her readers that she was a trustworthy writer who would try to supply convincing evidence throughout her paper.

The table below shows some of the many ways this common statement-support pattern can be used to clarify and substantiate your ideas.

| First: Statement, Claim, or Assertion | Then: Supporting Evidence |

| Introduces a topic | Facts or statistics to justify the importance or significance of the topic |

| Describes a situation | Factual examples or illustrations to convey reality or urgency |

| Introduces an event | Accurate firsthand observations to describe an event that you have witnessed |

| Presents a problem | Expert testimony or firsthand observation to establish the necessity or urgency of a solution |

| Explains an issue | Facts and details to clarify or justify the significance of the issue |

| States your point | Facts, statistics, or examples to support your viewpoint or position |

| Prepares for evidence that follows | Facts, examples, observations, or research findings to develop your case |

| Concludes with your recommendation or evaluation | Facts, examples, or expert testimony to persuade readers to accept your conclusion |

Use the following checklist to help you decide whether — and where — you might need supporting evidence from sources.

EVIDENCE CHECKLIST

- What does your thesis promise that you’ll deliver? What additional evidence would ensure that you effectively demonstrate your thesis?

- Are your statements, claims, and assertions backed up with supporting evidence? If not, what evidence might you add?

- What evidence would most effectively persuade your readers?

- What criteria for useful evidence matter most for your assignment or your readers? What evidence would best meet these criteria?

- Which parts of your paper sound weak or incomplete to you?

- What facts or statistics would clarify your topic?

- What examples or illustrations would make the background or the current circumstances clearer and more compelling for readers?

- What does a reliable expert say about the situation your topic involves?

- What firsthand observation would add authenticity?

- Where have peers or your instructor suggested more or stronger evidence?