Generating Ideas

For this assignment, you will need to select an issue, take a stand, develop a clear position, and assemble evidence that supports your view.

For more strategies for generating ideas, see Ch. 19.

Find an Issue. The topic for this paper should be an issue or controversy that interests both you and your audience. Try brainstorming a list of possible topics. Start with the headlines of a newspaper or newsmagazine, review the letters to the editor, check the political cartoons on the opinion page, or watch for stories on demonstrations or protests. You might also consult the library index to CQ Researcher, browse news or opinion Web sites, talk with friends, or consider topics raised in class. If you keep a journal, look over your entries to see what has perplexed or angered you. If you need to understand the issue better or aren’t sure you want to take a stand on it, investigate by freewriting, reading, or turning to other sources.

Once you have a list of possible topics, drop those that seem too broad or complex or that you don’t know much about. Weed out anything that might not hold your — or your readers’ — interest. From your new list, pick the issue or controversy for which you can make the strongest argument.

Start with a Question and a Thesis. At this stage, many writers try to pose the issue as a question — one that will be answered through the position they take. Skip vague questions that most readers wouldn’t debate, or convert them to questions that allow different stands.

| VAGUE QUESTION | Is stereotyping bad? |

| CLEARLY DEBATABLE | Should we fight gender stereotypes in advertising? |

You can help focus your position by stating it in a sentence — a thesis, or statement of your stand. Your statement can answer your question:

See more on stating a thesis.

| WORKING THESIS | We should expect advertisers to fight rather than reinforce gender stereotypes. |

| OR | Most people who object to gender stereotypes in advertising need to get a sense of humor. |

Your thesis should invite continued debate by taking a strong position that can be argued rather than stating a fact.

| FACT | Hispanics constitute 16 percent of the community but only 3 percent of our school population. |

| WORKING THESIS | Our school should increase outreach to the Hispanic community, which is underrepresented on campus. |

Use Formal Reasoning to Refine Your Position. As you take a stand on a debatable matter, you are likely to use reasoning as well as specific evidence to support your position. A syllogism is a series of statements, or premises, used in traditional formal logic to lead deductively to a logical conclusion.

| MAJOR STATEMENT | All students must pay tuition. |

| MINOR STATEMENT | You are a student. |

| CONCLUSION | Therefore, you must pay tuition. |

For a syllogism to be logical, ensuring that its conclusion always applies, its major and minor statements must be true, its definitions of terms must remain stable, and its classification of specific persons or items must be accurate. In real-life arguments, such tidiness may be hard to achieve.

For example, maybe we all agree with the major statement above that all students must pay tuition. However, some students’ tuition is paid for them through a loan or scholarship. Others are admitted under special programs, such as a free-tuition benefit for families of college employees or a back-to-college program for retirees. Further, the word student is general; it might apply to students at public high schools who pay no tuition. Next, everyone might agree that you are a student, but maybe you haven’t completed registration or the computer has mysteriously dropped you from the class list. Such complications can threaten the success of your conclusion, especially if your audience doesn’t accept it. In fact, many civic and social arguments revolve around questions such as these: What — exactly — is the category or group affected? Is its definition or consequence stable — or does it vary? Who falls in or out of the category?

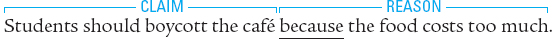

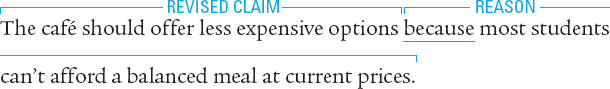

Use Informal Toulmin Reasoning to Refine Your Position. A contemporary approach to logic is presented by the philosopher Stephen Toulmin (1922–2009) in The Uses of Argument (2nd ed., 2003). He describes an informal way of arguing that acknowledges the power of assumptions in our day-to-day reasoning. This approach starts with a concise statement — the essence of an argument — that makes a claim and supplies a reason to support it.

You develop a claim by supporting your reasons with evidence — your data or grounds. For example, your evidence might include facts about the cost of lunches on campus, especially in contrast to local fast-food options, and statistics about the limited resources of most students at your campus.

However, most practical arguments rely on a warrant, your thinking about the connection or relationship between your claim and your supporting data. Because you accept this connection and assume that it applies, you generally assume that others also take it for granted. For instance, nearly all students might accept your assumption that a campus café should serve the needs of its customers. Many might also agree that students should take action rather than allow a campus facility to take advantage of them by charging high prices. Even so, you could state your warrant directly if you thought that your readers would not see the connection that you do. You also could back up your warrant, if necessary, in various ways:

- using facts, perhaps based on quality and cost comparisons with food service operations on other campuses

- using logic, perhaps based on research findings about the relationship between cost and nutrition for institutional food as well as the importance of good nutrition for brain function and learning

- making emotional appeals, perhaps based on happy memories of the café or irritation with its options

- making ethical appeals, perhaps based on the college mission statement or other expressions of the school’s commitment to students

As you develop your reasoning, you might adjust your claim or your data to suit your audience, your issue, or your refined thinking. For instance, you might qualify your argument (perhaps limiting your objections to most, but not all, of the lunch prices). You might also add a rebuttal by identifying an exception to it (perhaps excluding the fortunate, but few, students without financial worries due to good jobs or family support). Or you might simply reconsider your claim, concluding that the campus café is, after all, convenient for students and that the manager might be willing to offer more inexpensive options without a student boycott.

Toulmin reasoning is especially effective for making claims like these:

- Fact — Loss of polar ice can accelerate ocean warming.

- Cause — The software company went bankrupt because of its excessive borrowing and poor management.

- Value — Cell phone plan A is a better deal than cell phone plan B.

- Policy — Admissions policies at Triborough University should be less restrictive.

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

- What issue or controversy concerns you? What current debate engages you?

- What position do you want to take? How can you state your stand? What evidence might you need to support it?

- How might you refine your working thesis? How could you make statements more accurate, definitions clearer, or categories more exact?

- What assumptions are you making? What clarification of or support for these assumptions might your audience need?

- How might you qualify your thesis? What exceptions should you note? What other views might you want to recognize?

Select Evidence to Support Your Position. When you state your claim, you state your overall position. You also may state supporting claims as topic sentences that establish your supporting points, introduce supporting evidence, and help your reader follow your reasoning. To decide how to support a claim, try to reduce it to its core question. Then figure out what reliable and persuasive evidence might answer the question.

As you begin to look for supporting evidence, consider the issue in terms of the three general types of claims — claims that require substantiation, provide evaluation, and endorse policy.

- Claims of Substantiation: What Happened?

These claims require examining and interpreting information in order to resolve disputes about facts, circumstances, causes or effects, definitions, or the extent of a problem.

Sample Claims:

- Certain types of cigarette ads, such as the once-popular Joe Camel ads, significantly encouraged smoking among teenagers.

- Despite a few well-publicized exceptions, police brutality in this country is not a major problem.

- On the whole, bilingual education programs actually help students learn English more quickly than total immersion programs do.

Possible Supporting Evidence:

- Facts and information: parties involved, dates, times, places

- Clear definitions of terms: police brutality or total immersion

- Well-supported comparison and contrast: statistics to contrast “a few well-publicized exceptions” with a majority of instances that are “not a problem”

- Well-supported cause-and-effect analysis: authoritative information to demonstrate how actions of tobacco companies “significantly encouraged smoking” or bilingual programs “help students learn English faster”

- Claims of Evaluation: What Is Right?

These claims consider right or wrong, appropriateness or inappropriateness, and worth or lack of worth involved in an issue.

Sample Claims:

- Research using fetal tissue is unethical in a civilized society.

- English-only legislation promotes cultural intolerance in our society.

- Keeping children in foster care for years, instead of releasing them for adoption, is wrong.

Possible Supporting Evidence:

- Explanations or definitions of appropriate criteria for judging: deciding what’s “unethical in a civilized society”

- Corresponding details and reasons showing how the topic does or does not meet the criteria: details or applications of English-only legislation that meet the criteria for “cultural intolerance” or reasons with supporting details that show why years of foster care meet the criteria for being “wrong”

- Claims of Policy: What Should Be Done?

These claims challenge or defend approaches for achieving generally accepted goals.

Sample Claims:

- The federal government should support the distribution of clean needles to reduce the rate of HIV infection among intravenous drug users.

- Denying children of undocumented workers enrollment in public schools will reduce the problem of illegal immigration.

- All teenagers accused of murder should be tried as adults.

Possible Supporting Evidence:

- Explanation and definition of the policy goal: assuming that most in your audience agree that it is desirable to reduce “the rate of HIV infection” or “the problem of illegal immigration” or to try murderers in the same way regardless of age

- Corresponding details and reasons showing how your policy recommendation would meet the goal: results of “clean needle” trials or examples of crime statistics and cases involving teen murderers

- Explanations or definitions of the policy’s limits or applications, if needed: why some teens should not be tried as adults because of their situations

Consider Your Audience as You Develop Your Claim. The nature of your audience might influence the type of claim you choose to make. For example, suppose that the nurse or social worker at the high school you attended or that your children now attend proposed distributing free condoms to students. The following table illustrates how the responses of different audiences to this proposal might vary with the claim. As you develop your claims, try to put yourself in the place of your audience. For example, if you are a former student, what claim would most effectively persuade you? If you are the parent of a teenager, what claim would best address both your general views and your specific concerns about your own child?

| Audience | Type of Claim | Possible Effect on Audience |

| Conservative parents who believe that free condoms would promote immoral sexual behaviour | Evaluation: In order to save lives and prevent unwanted pregnancies, distributing free condoms in high school is our moral duty. | Counterproductive if the parents feel that they are being accused of immorality for not agreeing with the proposal |

| Conservative parents who believe that free condoms would promote immoral sexual behaviour | Substantiation: Distributing free condoms in high school can effectively reduce pregnancy rates and the spread of STDs, especially AIDS, without substantially increasing the rate of sexual activity among teenagers. | Possibly persuasive, based on effectiveness, if parents feel that their desire to protect their children from harm, no matter what, is recognized and the evidence deflates their main fear (promoting sexual activity) |

| School administrators who want to do what’s right but don’t want hordes of angry parents pounding down the school doors | Policy: Distributing free condoms in high school to prevent unwanted pregnancies and the spread of STDs, including AIDS, is best accomplished as part of a voluntary sex education program that strongly emphasizes abstinence as the primary preventative. | Possibly persuasive if administrators see that the proposal addresses health and pregnancy issues without setting off parental outrage (by proposing a voluntary program that would promote abstinence, thus addressing concerns of parents) |

See more about forms of evidence.

For more about using sources, see Ch. 12 and the Quick Research Guide beginning on p. A-20.

Assemble Supporting Evidence. Your claim stated, you’ll need evidence to support it. That evidence can be anything that demonstrates the soundness of your position and the points you make — facts, statistics, observations, expert testimony, illustrations, examples, and case studies.

The three most important sources of evidence are these:

- Facts, including statistics. Facts are statements that can be verified by objective means; statistics are facts expressed in numbers. Facts usually form the basis of a successful argument.

- Expert testimony. Experts are people with knowledge of a particular field gained from study and experience.

- Firsthand observation. Your own observations can be persuasive if you can assure your readers that your account is accurate.

See more on logical fallacies.

Of course, evidence must be used carefully to avoid defending logical fallacies — common mistakes in thinking — and making statements that lead to wrong conclusions. Examples are easy to misuse (claiming proof by example or too few examples). Because two professors you know are dissatisfied with state-mandated testing programs, you can’t claim that all — or even most — professors are. Even if you surveyed more professors at your school, you could speak only generally of “many professors.” To claim more, you might need to conduct scientific surveys, access reliable statistics from the library or Internet, or solicit the views of a respected expert in the area.

Record Evidence. For this assignment, you will need to record your evidence in written form in a notebook or a computer file. Note exactly where each piece of information comes from. Keep the form of your notes flexible so that you can easily rearrange them as you plan your draft.

See more on testing evidence.

Test and Select Evidence to Persuade Your Audience. Now that you’ve collected some evidence, sift through it to decide which information to use. Evidence is useful and trustworthy when it is accurate, reliable, up-to-date, to the point, representative, appropriately complex, and sufficient and strong enough to back the claim and persuade readers. You may find that your evidence supports a different stand than you intended to take. Might you find facts, testimony, and observations to support your original position after all? Or should you rethink your position? If so, revise your working thesis. Does your evidence cluster around several points or reasons? If so, use your evidence to plan the sequence of your essay.

See section B in the Quick Format Guide for more on the use of visuals and their placement.

In addition, consider whether information presented visually would strengthen your case or make your evidence easier for readers to grasp.

- Graphs can effectively show facts or figures.

- Tables can convey terms or comparisons.

- Photographs or other illustrations can substantiate situations.

Test each visual as you would test other evidence for accuracy, reliability, and relevance. Mention each visual in your text, and place the visual close to that reference. Cite the source of any visual you use and of any data you consolidate in your own graph or table.

Most effective arguments take opposing viewpoints into consideration whenever possible. Use these questions to help you assess your evidence from this standpoint.

ANALYZE YOUR READERS’ POINTS OF VIEW

- What are their attitudes? Interests? Priorities?

- What do they already know about the issue?

- What do they expect you to say?

- Do you have enough appropriate evidence that they’ll find convincing?

FOCUS ON THOSE WITH DIFFERENT OR OPPOSING OPINIONS

- What are their opinions or claims?

- What is their evidence?

- Who supports their positions?

- Do you have enough appropriate evidence to show why their claims are weak, only partially true, misguided, or just plain wrong?

ACKNOWLEDGE AND REBUT THE COUNTERARGUMENTS

- What are the strengths of other positions? What might you want to concede or grant to be accurate or relevant?

- What are the limitations of other positions? What might you want to question or challenge?

- What facts, statistics, testimony, observations, or other evidence supports questioning, qualifying, challenging, or countering other views?