Revising and Editing

What is your revision plan for your draft?

What is your revision plan for your draft?

Erin met with her peers and her instructor, collecting all the comments about her draft. To help her focus on the purpose of the essay, she reread the assignment. She decided that reflecting more would strengthen her main idea, or thesis—and her instructor had already pointed out the importance of a strong thesis in college writing.

What changes do you want to mark in your draft?

What changes do you want to mark in your draft?

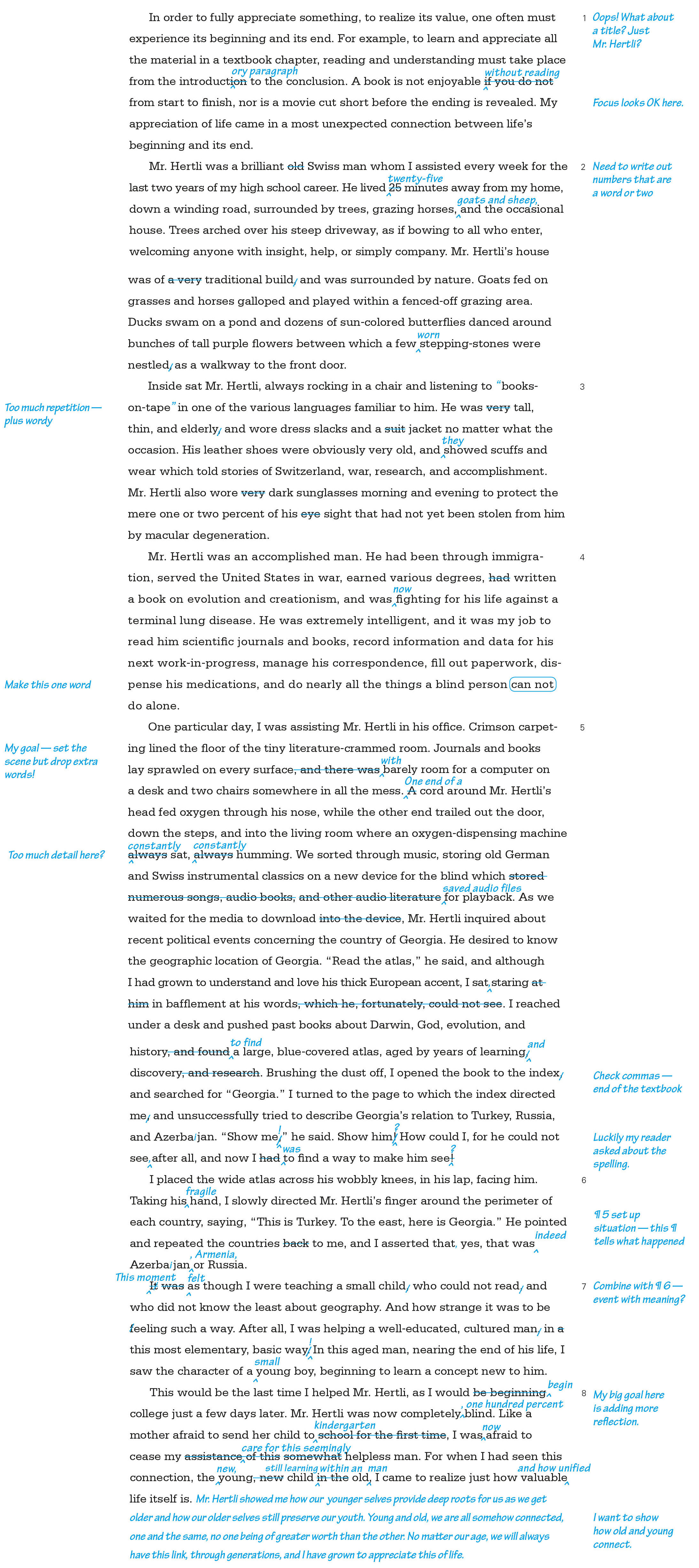

Erin concentrated first on revising her conclusion because all her readers had suggested strengthening it. Then she went back to the beginning to make other changes, responding to comments and editing details. Erin’s changes are marked in the following version of her draft. The comments in the margins point out some of her revision and editing decisions.

Revised and Edited Draft

How might you strengthen your essay as you revise and edit?

How might you strengthen your essay as you revise and edit?

After Erin finished revising and editing, she spell-checked her final version and proofread it one more time. Then she submitted her final draft.

Final Draft for Submission

For sample MLA paper format, see Business Letters in Ch. 17 and section E in the Quick Format Guide.

Erin Schmitt

Professor Hoeness-Krupsaw

ENG 101.004

19 September 2016

Mr. Hertli

1

In order to fully appreciate something, to realize its value, one often must experience its beginning and its end. For example, to learn and appreciate all the material in a textbook chapter, reading and understanding must take place from the introductory paragraph to the conclusion. A book is not enjoyable without reading from start to finish, nor is a movie cut short before the ending is revealed. My appreciation of life came in a most unexpected connection between life’s beginning and its end.

2

Mr. Hertli was a brilliant Swiss man whom I assisted every week for the last two years of my high school career. He lived twenty-five minutes away from my home, down a winding road, surrounded by trees, grazing horses, goats and sheep, and the occasional house. Trees arched over his steep driveway, as if bowing to all who enter, welcoming anyone with insight, help, or simply company. Mr. Hertli’s house was of traditional build and was surrounded by nature. Goats fed on grasses and horses galloped and played within a fenced-off grazing area. Ducks swam on a pond and dozens of sun-colored butterflies danced around bunches of tall purple flowers between which a few worn stepping-stones were nestled as a walkway to the front door.

3

Inside sat Mr. Hertli, always rocking in a chair and listening to “books-on-tape” in one of the various languages familiar to him. He was tall, thin, and elderly and wore dress slacks and a jacket no matter what the occasion. His leather shoes were obviously very old, and they showed scuffs and wear which told stories of Switzerland, war, research, and accomplishment. Mr. Hertli also wore dark sunglasses morning and evening to protect the mere one or two percent of his sight that had not yet been stolen from him by macular degeneration.

4

Mr. Hertli was an accomplished man. He had been through immigration, served the United States in war, earned various degrees, written a book on evolution and creationism, and was now fighting for his life against a terminal lung disease. He was extremely intelligent, and it was my job to read him scientific journals and books, record information and data for his next work-in-progress, manage his correspondence, fill out paperwork, dispense his medications, and do nearly all the things a blind person cannot do alone.

5

One particular day, I was assisting Mr. Hertli in his office. Crimson carpeting lined the floor of the tiny literature-crammed room. Journals and books lay sprawled on every surface with barely room for a computer on a desk and two chairs somewhere in all the mess. One end of a cord around Mr. Hertli’s head fed oxygen through his nose, while the other end trailed out the door, down the steps, and into the living room where an oxygen-dispensing machine constantly sat, constantly humming. We sorted through music, storing old German and Swiss instrumental classics on a new device for the blind which saved audio files for playback. As we waited for the media to download, Mr. Hertli inquired about recent political events concerning the country of Georgia. He desired to know the geographic location of Georgia.“Read the atlas,” he said, and although I had grown to understand and love his thick European accent, I sat, staring in bafflement at his words. I reached under a desk and pushed past books about Darwin, God, evolution, and history to find a large, blue-covered atlas, aged by years of learning and discovery. Brushing the dust off, I opened the book to the index and searched for “Georgia.” I turned to the page to which the index directed me and unsuccessfully tried to describe Georgia’s relation to Turkey, Russia, and Azerbaijan.“Show me!” he said. Show him? How could I, for he could not see, after all, and now I was to find a way to make him see?

6

I placed the wide atlas across his wobbly knees, in his lap, facing him. Taking his fragile hand, I slowly directed Mr. Hertli’s finger around the perimeter of each country, saying, “This is Turkey. To the east, here is Georgia.” He pointed and repeated the countries to me, and I asserted that, yes, that was indeed Azerbaijan, Armenia, or Russia. This moment felt as though I were teaching a small child, one who could not read and who did not know the least about geography. And how strange it was to be feeling such a way. After all, I was helping a well-educated, cultured man in this most elementary, basic way! In this aged man, nearing the end of his life, I saw the character of a small young boy, beginning to learn a concept new to him.

7

This would be the last time I helped Mr. Hertli, as I would begin college just a few days later. Mr. Hertli was now completely, one hundred percent blind. Like a mother afraid to send her child to kindergarten, I was now afraid to cease my care for this seemingly helpless man. For when I had seen this connection, the new, young child still learning within an old man, I came to realize just how valuable and how unified life itself is. Mr. Hertli showed me how our younger selves provide deep roots for us as we get older and how our older selves still preserve our youth. Young and old, we are all somehow connected, one and the same, no one being of greater worth than the other. No matter our age, we will always have this link, through generations, and I have grown to appreciate this of life.