A Process of Writing

For full chapters on stages of the writing process, see Chs. 18–24.

Writing can seem at times an overwhelming drudgery, worse than scrubbing floors; at other moments, it’s a sport full of thrills—like whizzing downhill on skis, not knowing what you’ll meet around a bend. Unpredictable as the process may seem, nearly all writers do similar things:

They generate ideas.

They plan, draft, and develop their papers.

They revise and edit.

These three activities form the basis of most effective writing processes, and they lie at the heart of each writing situation in this book.

Getting Started

Two considerations—what you want to accomplish as a writer and how you want to appeal to your audience—will shape the direction of your writing. Clarifying your purpose and considering your audience are likely to increase your confidence as a writer. Even so, your writing process may take you in unexpected directions, not necessarily in a straight line. You can skip around, work on several parts at a time, test a fresh approach, circle back over what’s already done, or stop to play with a sentence until it clicks.

Generating Ideas

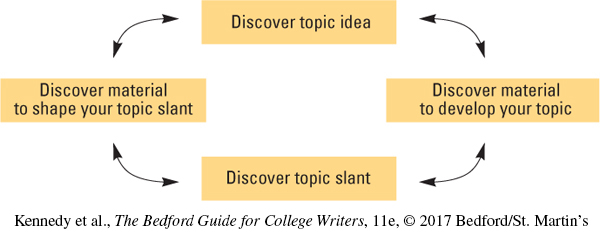

The first activity in writing—finding a topic and something to say about it—is often the most challenging and least predictable. The chapter section titled “Generating Ideas” is filled with examples, questions, checklists, and visuals designed to trigger ideas that will help you begin the writing assignment.

Discovering What to Write About. You may get an idea while texting friends, riding your bike, or staring out the window. Sometimes a topic lies near home, in a conversation or an everyday event. Often, your reading will raise questions that call for investigation. Even if an assignment doesn’t appeal to you, your challenge is to find a slant that does. Find it, and words will flow—words to engage readers and accomplish your purpose.

Discovering Material. To shape and support your ideas, you’ll need facts and figures, reports and opinions, examples and illustrations. How do you find supporting material that makes your slant on a topic clear and convincing? Luckily you have many sources at your fingertips. You can recall your experience and knowledge, observe things around you, talk with others who are knowledgeable, read enlightening materials that draw you to new approaches, and think critically about all these sources.

For an online class discussion of writing processes, see Common Online Writing Situations in Ch. 15.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Ideas

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Ideas

Reflecting on Ideas

Think over past writing experiences at school or work. How do you get ideas? Where do they come from? Where do you turn for related material? What are your most reliable sources of inspiration and information? Share your experiences with others in class or online, noting any new approaches you would like to try.

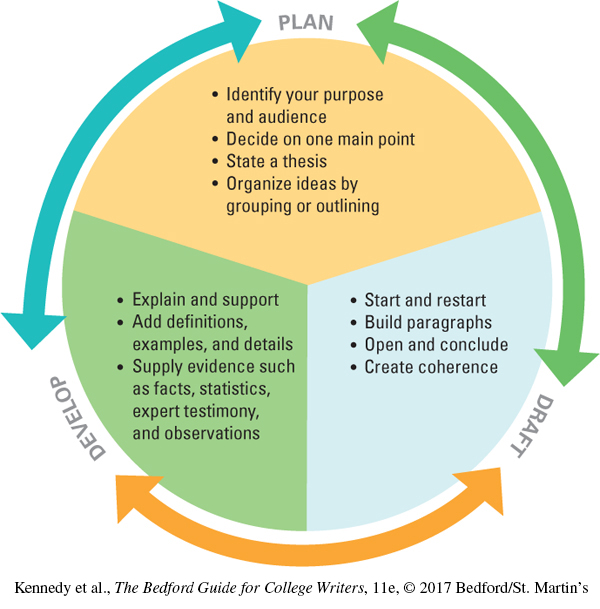

Planning, Drafting, and Developing

Next you will plan your paper, write a draft, and develop your ideas further. The section titled “Planning, Drafting, and Developing” will help you through these stages for the assignment in that chapter.

Planning. Having discovered a burning idea to write about (or at least a smoldering one) and some supporting material (but maybe not enough yet), you’ll sort out what matters most. If you see one main point, or thesis, test various ways of stating it, given your purpose and audience:

| MAYBE | Parking in the morning before class is annoying. |

| OR | Campus parking is a big problem. |

Next, arrange your ideas and material in a sensible order that will clarify your point. For example, you might group and label your ideas, make an outline, or analyze the main point, breaking it down into parts:

Parking on campus is a problem for students because of the long lines, inefficient entrances, and poorly marked spaces.

But if no clear thesis emerges quickly, don’t worry. You may find one while you draft—that is, while you write an early version of your paper.

Drafting. As your ideas begin to appear, write them down before they can go back into hiding. When you take risks at this stage, you’ll probably be surprised and pleased at what happens, even though your first version will be rough. Writing takes time; a paper usually needs several drafts and maybe a clearer introduction, a stronger conclusion, more convincing evidence, or even a fresh start.

For advice on using a few sources, see the Quick Research Guide.

Developing. Weave in explanations, definitions, examples, and other evidence to make your ideas clear and persuasive. For example, you may define an at-risk student, illustrate the problems of single parents, or supply statistics about hit-and-run accidents. If you need specific support for your point, use strategies for developing ideas—or return to those for generating ideas. Work in your insights if they fit.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Drafts

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Drafts

Reflecting on Drafts

Reflect on your past writing experiences. How do you usually plan, draft, and develop your writing? How well do your methods work? How do you adjust them to the situation or type of writing you’re doing? Which part of producing a draft do you most dread, enjoy, or wish to change? Why? Write down your reflections, and then share your experiences with others.

Revising and Editing

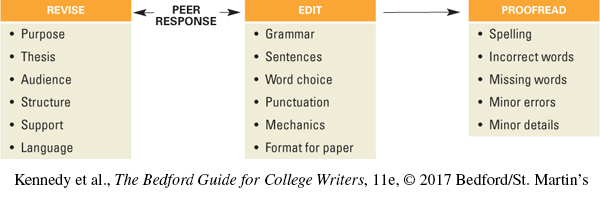

You might be tempted to relax once you have a draft, but for most writers, revising begins the work in earnest. Each “Revising and Editing” section provides checklists as well as suggestions for working with a peer.

Revising. Revising means both reseeing and rewriting, making major changes so your paper does what you want it to. You might reconsider your purpose and audience, rework your thesis, decide what to put in or leave out, move paragraphs around, and connect ideas better. Perhaps you’ll add costs to a paper on parking problems or switch attention from mothers to fathers as you consider single parents.

If you put aside your draft for a few hours or a day, you can reread it with fresh eyes and a clear mind. Other students can also help you by responding to your drafts as engaged readers.

For editing advice, see the Quick Editing Guide. For format advice, see the Quick Format Guide.

Editing. Editing means refining details, improving wording, and correcting flaws that may stand in the way of your readers’ understanding and enjoyment. Don’t edit too early, though, because you may waste time on parts that you later revise out. In editing, you usually make these repairs:

Drop unnecessary words; choose lively and precise words.

Replace incorrect or inappropriate wording.

Rearrange words in a clearer, more emphatic order.

Combine short, choppy sentences, or break up long, confusing ones.

Refine transitions for continuity of thought.

Check grammar, usage, punctuation, and mechanics.

Proofreading. Finally you’ll proofread, taking a last look, checking correctness, and catching doubtful spellings or word-processing errors.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Finishing

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Finishing

Reflecting on Finishing

Think over past high-pressure writing experiences, such as major papers at school or reports at work. What steps do you take to rethink and refine your writing before submitting or posting it? What prompts you to make major changes? How do you try to satisfy concerns of your main reader or a broader audience? Work with others in class or online to collect and share your best ideas about wrapping up writing projects.