Reading on Literal and Analytical Levels

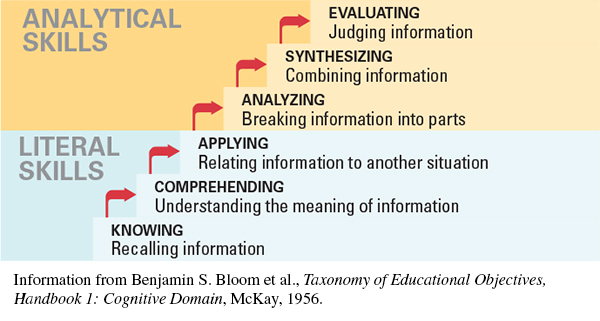

Educational expert Benjamin S. Bloom identified six levels of cognitive activity: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.1 (A recent update recasts synthesis as creating and moves it above evaluation to the highest level.) Each level acts as a foundation for the next. Each also demands higher thinking skills than the previous one. Experienced readers, however, jump among these levels, gathering information and insight as they occur.

The first three levels are literal skills, building blocks of thought. The last three levels—analysis, synthesis, and evaluation—are analytical skills that your instructors especially want you to develop. To read critically, you must engage with a reading on both literal and analytical levels. Suppose you read in your history book a passage about Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), the only American president elected to four consecutive terms.

Knowing. Once you read the passage, even if you have little background in American history, you can decode and recall the information it presents about FDR and his four terms in office.

Comprehending. To understand the passage, you need to know that a term for a U.S. president is four years and that consecutive means “continuous.” Thus FDR was elected to serve for sixteen years.

Applying. To connect this knowledge to what you already know, you think of other presidents—George Washington, who served two terms; Grover Cleveland, who served two terms but not consecutively; Jimmy Carter, who served one term; the second George Bush, who served two terms. You realize that four terms are quite unusual. In fact, the Twenty-Second Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1951, now limits a president to two terms.

Analyzing. You can scrutinize FDR’s election to four terms from various angles, selecting a principle for analysis that suits your purpose. Then you can use this principle to break the information into its components or parts. For example, you might analyze FDR’s tenure in relation to that of other presidents. Why has FDR been the only president elected to serve four terms? What circumstances contributed to three reelections?

Synthesizing. To answer your questions, you may read more or review past readings. Then you begin synthesizing—creating a new approach or combination by pulling together facts and opinions, identifying evidence accepted by all or most sources, examining any controversial evidence, and drawing conclusions that reliable evidence seems to support. For example, you might logically conclude that the special circumstances of the Great Depression and World War II contributed to FDR’s election to four terms, not that Americans reelected him out of pity because he had polio.

Evaluating. Finally, you evaluate the significance of your new knowledge for understanding Depression-era politics and assessing your history book’s approach. You might ask yourself, Why has the book’s author chosen to make this point? How does it affect the rest of the discussion? You may also have concluded that FDR’s four-term presidency is understandable in light of the events of the 1930s and 1940s, that the author has mentioned this fact to highlight the era’s unique political atmosphere, and that it is evidence neither for nor against FDR’s excellence as a president.

Learning by Doing Reading Analytically

Learning by Doing Reading Analytically

Reading Analytically

Think back to something you’ve read recently that helped you make a decision, perhaps a newspaper or magazine article or an electronic posting. How did you analyze what you read, breaking the information into parts? How did you synthesize it, combining it with what you already knew? How did you evaluate it, judging its significance for your decision?

Generating Ideas from Reading

For more on generating ideas, see Ch. 19.

Like flint that strikes steel and causes sparks, readers and writers provoke one another. For example, when your class discusses an essay, you may be surprised by the range of insights your classmates report. Of course, they may be equally surprised by what you see. Above all, reading is a dynamic process. It may change your ideas instead of support them. Here are suggestions for unlocking the potential of a good text.

Looking for Meaty Pieces. Spur your thinking about current topics by browsing through essay collections or magazines in the library or online. Try the Atlantic, Harper’s, New Republic, Commentary, or special-interest magazines such as Architectural Digest or Scientific American. Check editorials and op-ed columns in your local newspaper, the New York Times, or the Wall Street Journal. Search the Internet on intriguing topics (such as silent-film technology) or issues (such as homeless children). Look for meaty, not superficial, articles written to inform and convince, not entertain or amuse.

Logging Your Reading. For several days keep a log of the articles that you find. Record the author, title, and source for each promising piece so that you can easily find it again. Briefly note the subject and point of view as well, so you can identify a range of possibilities.

Recalling Something You Have Already Read. What have you read lately that started you thinking? Return to a reading—a chapter in a history book, an article for sociology, a research report for biology.

Paraphrasing and Summarizing Complex Ideas. Do you feel overwhelmed by challenging reading? If so, read slowly and carefully. Try two common methods of recording and integrating ideas from sources into papers.

Paraphrase: restate an author’s complicated ideas fully but in your own language, using different wording and different sentence patterns.

Summarize: reduce an author’s main point to essentials, using your own clear, concise, and accurate language.

Accurately recording what a reading says can help you grasp its ideas, especially on literal levels. Once you understand what it says, you can agree, disagree, or question.

Reading Critically. Instead of just soaking up what a reading says, try a conversation with the writer. Criticize. Wonder. Argue back. Demand convincing evidence. Use the following checklist to get started.

CRITICAL READING CHECKLIST

What problems and issues does the author raise?

What is the author’s purpose? Is it to explain or inform? To persuade? To amuse? In addition to this overall purpose, is the author trying to accomplish some other agenda?

How does the author appeal to you as a reader? Where do you agree and disagree? Where do you want to say “Yeah, right!” or “I don’t think so!”? Does the topic or approach engage you?

How does this piece relate to your own experiences or thoughts? Have you encountered anything similar?

Are there important words or ideas that you don’t understand? If so, do you need to reread or turn to a dictionary or reference book?

For more on facts and opinions, see Consider Your Audience as You Develop Your Claim in Ch. 9.

What is the author’s point of view? What does the author assume or take for granted? Where does the author reveal these assumptions? Do they make the selection seem weak or biased?

For more on evaluating evidence, see section C in the Quick Research Guide.

Which statements are facts, verifiable by observation, firsthand testimony, or research? Which are opinions? Does one or the other dominate?

Is the writer’s evidence accurate, relevant, and sufficient? Is it persuasive?

Analyzing Writing Strategies. Reading widely and deeply can reveal what others say and how they shape and state it. For some readings in this book, notes in the margin identify key features such as the introduction, thesis statement or main idea, major points, and supporting evidence. Ask questions such as these to help you identify writing strategies:

WRITING STRATEGIES CHECKLIST

How does the author introduce the reading and try to engage the audience?

Where does the author state or imply the main idea or thesis?

How is the text organized? What main points develop thesis?

How does the author supply support—facts, data, expert opinions, explanations, examples, other information?

How does the author connect or emphasize ideas for readers?

How does the author conclude the reading?

What is the author’s tone? How do the words and examples reveal the author’s attitude, biases, or assumptions?