Moving from Research Question to Working Thesis

For more on stating and using a thesis, see Shaping Your Topic for Your Purpose and Your Audience in Ch. 20.

Some writers find a project easier to tackle if they have in mind not only a question but also a possible answer, maybe even a working thesis. However, be flexible, ready to change either your possible answer or your question as your research progresses.

Take Action Focusing a Research Question

Ask each question listed in the left-hand column to consider whether your research question needs improvement. If so, follow the ASK—LOCATE SPECIFICS—TAKE ACTION sequence to revise.

| 1 ASK | 2 LOCATE SPECIFICS | 3 TAKE ACTION |

| Does my question focus on a topic that could be more interesting to me or my readers? |

|

TOO NARROW: How did John F. Kennedy’s maternal grandfather influence the decisions JFK made during his first month in office? BROADER: How did John F. Kennedy’s family influence his handling of the Cuban missile crisis? |

| Does my question address a debatable issue? Does it allow for a range of opposing viewpoints? Will I be able to support my own view rather than explain what’s generally known and accepted? |

|

TOO FACTUAL: Are there more African American students or white students in the entering class this year? MORE DEBATABLE: How does the racial or ethnic diversity of students affect campus relations at our school? |

| Is my question narrow enough for a productive investigation in the allotted time frame? |

|

TOO BROAD: How is the climate of the earth changing? NARROWER: How will El Niño affect the climate in California during the next decade? |

| RESEARCH QUESTION | How does a nutritious lunch benefit students? |

| WORKING THESIS | Nutritious school lunches can improve students’ classroom performance. |

Using Your Working Thesis to Guide Your Research

You probably will revise or replace your working thesis before you finish, but it can guide you now.

Identify terms to define and subtopics or components to explore.

List or informally outline points you might develop.

Note opposing views, alternatives, or solutions likely to emerge.

This early exploration will help you pursue the sources and information you need but avoid any wild-goose chase that might distract you.

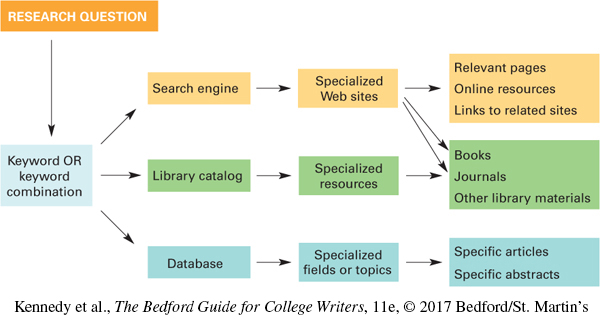

Surveying Your Resources

For Internet and library search strategies, see Ch. 31.

For advice on creating a working bibliography, see Starting a Working Bibliography in Ch. 33.

Conduct a quick online search of your library to test whether your question is likely to lead to an ample research paper. You’ll need enough ideas, opinions, facts, statistics, and expert testimony to address your question. If you turn up a skimpy list, change search terms. If your search results in hundreds of sources, refine your question. Aim for a question that is the focus of from twelve to twenty available sources. If you need help, talk to a reference librarian.

Also decide which types of sources to target. Some questions require a wide range and others a narrower range restricted by date or discipline. The list below describes a number of source types you can investigate.

Opinions on controversies. Turn to newspaper editorials, opinion columns, issue-oriented sites, and partisan groups for diverse views.

News and analysis. Look for stories from newsmagazines, newspapers, news services, and public broadcasting.

Statistics and facts. Try census or other government data, library databases, annual fact books, and almanacs.

Professional or workforce information. Turn to reports and surveys with academic, government, and corporate sponsors to reduce bias.

Research-based analysis. Try scholarly or well-researched nonfiction, government reports, specialized references, and academic databases.

Original records or images. Check archives, online historical records, and materials held by institutions such as the Library of Congress.