Searching the Library

What would you pay for access to a 24/7 Web site designed to make the most of your research time? What if it also screened and organized reliable sources for you–and tossed in free advice from information specialists? Whatever your budget, you’ve probably already paid–through your tuition–for these services. To get your money’s worth, simply use your student ID to access your college library, online or on campus.

Getting to Know the Library

Visit the library home page for an overview of resources such as these:

the online catalog for finding the library’s own books, journals, newspapers, and materials you can read or check out on campus

databases (with subscription fees paid) for electronic access to scholarly or specialized citations, abstracts, articles, and other resources

access to the resources of the state, region, or nation through interlibrary loan (ILL), a regional consortium, or a trip to a nearby library

links for finding specialized campus libraries, archives, or collections

pages, tutorials, and tours for advice on using the library productively

To introduce you to the campus library, your instructor may arrange a class orientation. If not, visit the library Web site and campus facility yourself.

RESEARCH CHECKLIST

Accessing Library Resources

What services, materials, and information does the home page present?

How do you gain online access to the library from your own computer? What should you do if you have trouble logging in?

How can you get live help from library staff: by drop-in visit, appointment, phone, e-mail, text message, chat, or other technology?

What resources–such as the library catalog and databases–can you search in the library, on campus, or off campus?

How can you identify databases useful for your project? What tutorials from the library or database provider show how to use them efficiently?

Page 620How are print books, journals, magazines, or newspapers organized?

How do you find specialized resources such as government documents, maps, legal records, statistics, videos, images, recordings, or local historical archives? Have you consulted a subject librarian?

Where can you study individually or meet with a group in the library?

What links or no-fee access to reliable Web sites, search engines such as Google Scholar, or academic style guides does the library provide?

What other services–copying, printing, computer access–are available at your library?

ABC

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Library Orientation Session

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Library Orientation Session

Reflecting on Your Library Orientation Session

After visiting the library for your class orientation, list the most useful things you have learned–such as directions for access, advice about off-campus use, ways to get search advice, specific resources for your project or major, types of materials new to you, the name of a reference librarian, or helpful tricks for doing faster research. Then list your current questions about your own research project, and figure out where to start looking for the best and fastest answers.

Target Your Search. Your campus library may surprise you with its sophisticated technology and easy access to an overwhelming array of resources. Identify and hunt for what you want to find.

Do you need a mixture of sources? Use the catalog to find specialized books or journals, databases to identify individual articles, reference books to look up definitions or overviews, or government sites or indexes to find reports. If your library offers WorldCat Local or a megasearch system, you can search all types of resources at one time.

Do you need current or historical information? Look for articles in periodicals (regularly published newspapers, magazines, and journals) for news of the day, week, or year. Turn to scholarly books for well-seasoned discussions.

Does your instructor require articles from peer-reviewed or refereed journals? Use Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory or databases to screen for journals that rely on expert reviewers to assess articles considered for publication.

Do you need opinions about current issues? Search databases for newspapers or magazines that carry opinion pieces, issue-oriented or investigative articles, or contrasting regional, national, or international views.

Do you need the facts? Check state or federal agencies or nonprofit groups for statistics about people, such as those in your zip code, including information about their education, employment, or health.

Use the Resources. Your campus library can help you become a more efficient and productive student. Try its wide variety of resources, advice, and tools: e-books, audio books, podcasts, videos, tutorials, workshops, citation managers, source organizers, and apps for academic tasks (e.g., note takers, time managers, project schedules, group organizers, and file hosting services).

Sample the Field. Many libraries supply Library Guides or lists of well-regarded starting points for research within a field. These valuable shortcuts help you quickly find a cluster of useful resources. The chart below supplies only a small sampling of the specialized indexes, dictionaries, encyclopedias, handbooks, yearbooks, and other resources available.

| Specialized Online Indexes | Print Reference Works | Online Government Resources | Internet Resources | |

| Humanities | Essay and General Literature Index; JSTOR | The Humanities: A Selective Guide to Information Sources | EDSITEment (NEH) | Voice of the Shuttle |

| Film and Theater | Film & Television Literature Index; Films on Demand | The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance | Smithsonian Archives Center: Film, Video, and Audio Collections | Cambridge Companions Online |

| History | Historical Abstracts America: History and Life | Dictionary of Concepts in History | The Library of Congress: American Memory | WWW Virtual Library: History Central Catalogue |

| Literature | MLA International Bibliography | Encyclopedia of the Novel | National Endowment for the Humanities | American Studies Journals |

| Social Sciences | Social Sciences Citation Index | International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences | Fedstats | e-Source from the National Institutes of Health |

| Education | Education Abstracts | International Encyclopedia of Education | National Center for Education Statistics | ERIC: Education Resources Information Center |

| Political Science | Worldwide Political Science Abstracts | State Legislative Sourcebook | FedWorld | Political Resources on the Net; National Security Archive |

| Women’s Studies | Women’s Studies International | Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia | U.S. Department of Labor Women’s Bureau | Institute for Women’s Policy Research |

| Science and Technology | General Science Abstracts; Web of Science | McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology | National Science Foundation | EurekAlert! |

| Earth Sciences | GeoRef | Facts on File Dictionary of Earth Science | USGS (U.S. Geological Survey): Science for a Changing World | Center for International Earth Science Information Network |

| Environmental Studies | Environmental Abstracts | Encyclopedia of Environmental Science | EPA: U.S. Environmental Protection | EnviroLink |

| Life Sciences | Biological Abstracts | Encyclopedia of Human Biology | National Agricultural Library | CAPHIS Top 100 List |

Using the Library Catalog

A library’s catalog is an index of all materials–books, periodicals, digital collections, historical archives, and so on–that the library houses. The catalog may also provide a listing of external materials that may be retrieved through interlibrary loan. The purpose of the catalog is to allow you to find basic information, such as title, author, and date, on materials that you can access through the library.

Search Creatively. Electronic catalogs may allow many search options, as the chart below illustrates. Consult a librarian or follow the prompts to find out which searches your catalog allows.

| Type of Search | Explanation | Examples | Search Tips |

| Keyword | Terms that identify topics discussed in source, including works by or about an author, but may generate long lists of relevant and irrelevant sources |

|

Use a cluster of keywords to avoid broad terms (whale, nursing) or to reduce irrelevant topics using the same terms (people of color, color graphics) |

| Subject | Terms assigned by library catalogers, often following the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) |

|

Consult the online LCSH or note the linked subject headings with search results to find the exact phrasing used |

| Author | Name of individual, organization, or group, leading to list of print (and possibly online) works by author (or editor) |

|

Begin as directed with an individual’s last name first; for a group, first do a keyword search to identify its exact name |

| Title | Name of book, pamphlet, journal, magazine, newspaper, video, CD, or other material |

|

Look for a separate search option for titles of periodicals (journals, newspapers, magazines) |

| Identification Numbers | Library or consortium call numbers, publisher or government publication numbers |

|

Use the call number of a useful source to find related items online or shelved nearby |

| Dates | Publication or other dates used to search (or limit searches) for current or historical materials |

|

Add dates to keyword or other searches to limit the topics or time of publication |

Learning by Doing Brainstorming for Search Terms

Learning by Doing Brainstorming for Search Terms

Brainstorming for Search Terms

Start with a class topic or your rough ideas for a research question. Working with a classmate or small group, brainstorm in class or online for keywords or synonyms that might be useful search terms for each person’s topic. Test your terms by searching several places–the library catalog, a subject-area database, a newspaper database, a reliable consumer Web page, a relevant government agency, or other library resources. Compare search results in terms of type, quantity, quality, and relevance of sources. Note which terms work best in which situations. Then refine your search terms–add limitations, change keywords, narrow the ideas, and so forth. Search again, trying to increase the relevance of what you find.

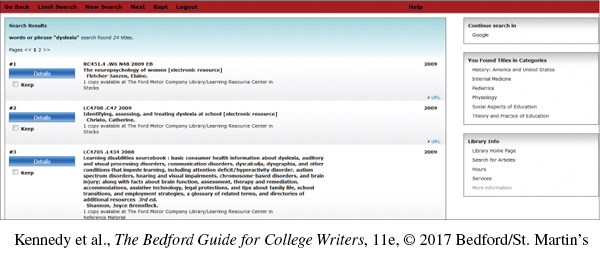

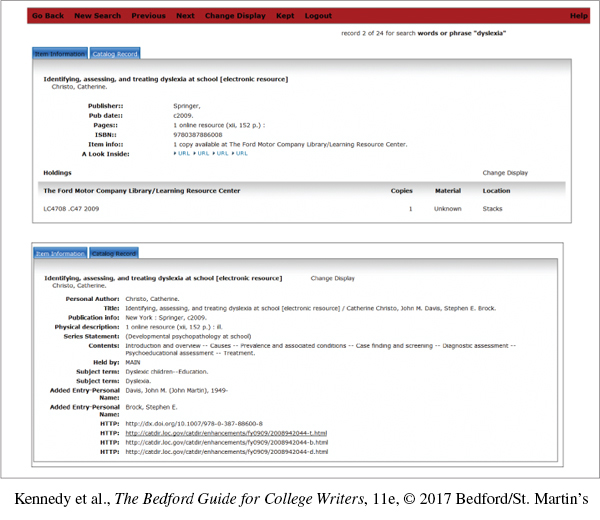

Sort Your Search Results. When your search produces a list of possible sources, click on the most promising items to learn more about them. See Figure 31.4 for a sample keyword search and Figure 31.5 for the online records for one source. Besides the call number or shelf location, the record will identify the author, the title, the place of publication, the date, and often the resource’s contents, length, and scope and search terms that may help focus your search. Use these clues to help you select options wisely.

ABC

ABCDEFG

Browse the Shelves. A call number, like an address, tells where a book or other resource “resides.” College libraries generally use the Library of Congress system, with letters and numbers, rather than the numerical Dewey decimal system, but both systems group items by subject. With a call number from an online record, follow the library map and section signs to the shelf with a promising book. Once there, browse through its intriguing neighbors, which often treat the same subject.

Searching Library Databases

Databases gather information. Your library may subscribe to dozens or hundreds to give you easy access to current screened resources, including hard-to-find fee-based Web sources. Check the library site for its database descriptions and lists by topic or field. A librarian can help match your research question to the databases most likely to provide what you need.

General databases with citations, abstracts, or full-text articles from many fields: Academic Search Premier, General OneFile, LexisNexis, OmniFile Full Text

- Page 626

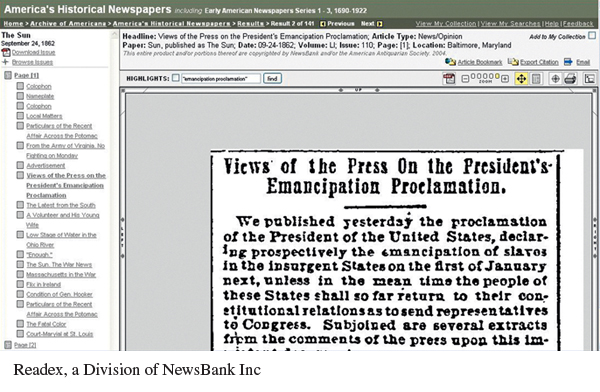

General-interest databases with news and culture of the time: Readers’ Guide Full-Text or Retrospective (popular periodicals); Historical New York Times, America’s Historical Newspapers, LexisNexis (news)

Specialized databases by type of material: JSTOR, Project MUSE, Sage (scholarly journals); Biological Abstracts (summaries of sources); WorldCat (books); American Periodicals Series Online (digitized magazines from 1741 to 1900)

Specialized databases by field: MedlinePlus, ScienceDirect, GreenFILE (biology, medicine, health); ABI/INFORM (business); AGRICOLA (agriculture)

Issue-oriented databases: PAIS International (public affairs); CQ Researcher (featured issues); Opposing Viewpoints in Context (debatable topics)

Reference databases: Gale Virtual Reference Library, Oxford Reference, Credo Reference

For specific information, select a database that covers the exact field, scholarly level, type of source, or time period that you need. Databases identify sources only in publications they analyze and only for dates they cover. Take tricky research problems to a subject librarian, who may suggest using a different database or older print or CD-ROM indexes for historical research.

Keywords. Start your search with the keywords in your research question:

| college costs | campus budgets | wetlands |

If your first search produces too many sources, narrow your terms:

college tuition increases

state campus budget cuts

Illinois wetlands and Great Midwestern Flood

Or add specifics, such as an author, a title, or a date.

Advanced Searches. Fill in the database’s advanced search screen to restrict by date or other options, or try common search options. For example, a database might allow wildcard or truncation symbols to find all forms of a term; often * is used for multiple and ? for individual characters (results are limited to the number of characters supplied in the original search).

| child* | children, childcare, childhood |

| wa? | wan, wag, wad |

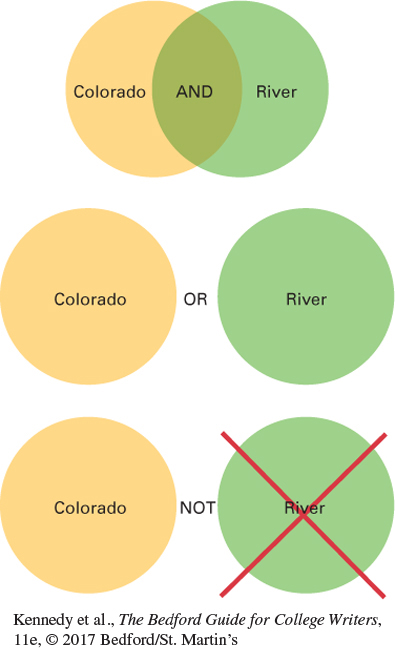

A database also might allow Boolean searches that combine or rule out terms:

| AND (narrows: all terms must appear in a result) | Colorado and River |

| OR (expands: any one of the terms must appear) | Colorado or River |

| NOT (rules out: one term must not appear) | Colorado not River |

Search Returns. Your search calls up a list of records or entries that include your search terms. Click on one of these for specifics about the item (title, author, publication information, date, other details) and possibly a description or summary (often called an abstract) or a link to the full text of the item. When you find a useful item, read, take notes, print, save, or e-mail the citation or article to yourself, as your system allows. If the database supplies only an abstract, read it to decide whether you need to track down the full article elsewhere.

RESEARCH CHECKLIST

Selecting Periodical Articles from a Database

What does the periodical title suggest about its audience, interest area, and popular or scholarly orientation? How likely are its articles to supply what you need?

Have the periodical articles been peer-reviewed (evaluated by other scholars prior to acceptance for publication), edited and fact-checked by journalists, or accepted for publication based on popular appeal?

Does the title or description of the article suggest that it will answer your research question? Or does the entry sound intriguing but irrelevant?

- Page 628

Does the date of the article fit your need for current, contemporary, eyewitness, or classic material?

Does the length of the article suggest that it’s a short review, a concise overview, or an exhaustive discussion? How much detail will you need?

Does the database offer the full text of the article in direct-scan PDF or reformatted html? If not, is the periodical likely to be available from another database, on its Web site, or on your library’s shelves?

Learning by Doing Comparing Databases

Learning by Doing Comparing Databases

Comparing Databases

Work with others interested in a particular subject or field. Pick at least three databases in that area. For each, investigate what type of response it provides (source references, abstracts, summaries, full-text articles), which dates it covers, how extensive its collection might be, and how you can most successfully use it. Report back to your group or to the entire class.

Using Specialized Library Resources

Many other library resources are available to you beyond what’s accessible from your library’s home page. If you need help locating or using materials, consult a librarian. Be sure to request the most current information, as not all reference resources are updated yearly.

ABC

| Types of Specialized Library Resources | Description | Examples |

| Encyclopedias | Multivolume general references can help you survey a topic; specialized encyclopedias cover a field in much greater depth. | Encyclopedia of Psychology; Encyclopedia of World Cultures; Gale Encyclopedia of Science |

| Dictionaries | Specialized dictionaries cover foreign languages, abbreviations, and slang as well as the terminology of a particular field. | Black’s Law Dictionary; Stedman’s Medical Dictionary; Oxford Dictionary of Natural History |

| Handbooks and Companions | Concise articles survey terms and topics on a specific subject. | Handbook of Special Education; Bloomsbury Guide to Women’s Literature |

| Government Documents | The U.S. government makes a large number of documents available on the Web, plus print and electronic indexes, some available only through libraries. | Congressional Record Index; Statistical Abstract of the United States |

| Atlases | Maps of countries and regions as well as their history, natural resources, and ethnic groups and other topics. | Atlas of Structural Geology |

| Biographical Sources | Basic information about prominent people. | American Men and Women of Science; Who’s Who in Politics |

| Bibliographies | List a wide variety of sources on a specific subject and research others have already done. | The Essential Shakespeare: An Annotated Bibliography of Major Modern Studies |

| Specialized Materials | Other collections, especially those of local or specialized topics. Some collections may be digitized. | Diaries and letters; photographs; pamphlets; unpublished manuscripts |