Bonnie Berkowitz and Laura Stanton, “Roller Coasters: Feeling Loopy”

BONNIE BERKOWITZ AND LAURA STANTON

Bonnie Berkowitz and Laura Stanton are graphic artists at the Washington Post. A graduate of the University of Kansas, Berkowitz has researched and produced health and science pieces for the Post since 1995. She has also worked for several other newspapers, including the Miami Herald, the Orlando Sentinel, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Stanton graduated from the University of Notre Dame, freelanced for more than twenty years, and worked for the Chicago Tribune and the Dallas Morning News before joining the Post. The two frequently work together to create informative, visually rich infographics on topics that readers can easily relate to.

“Roller Coasters: Feeling Loopy”

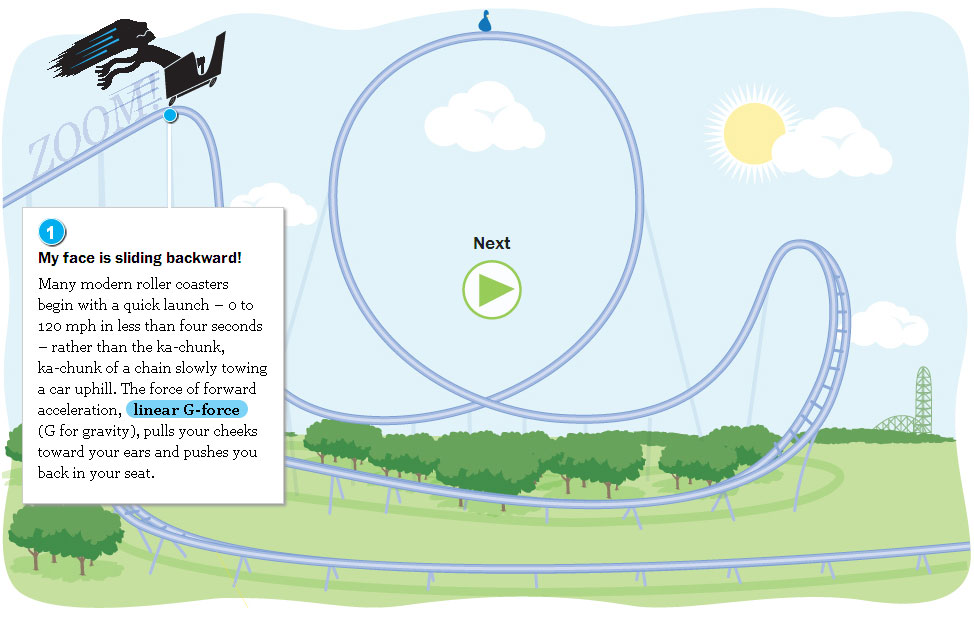

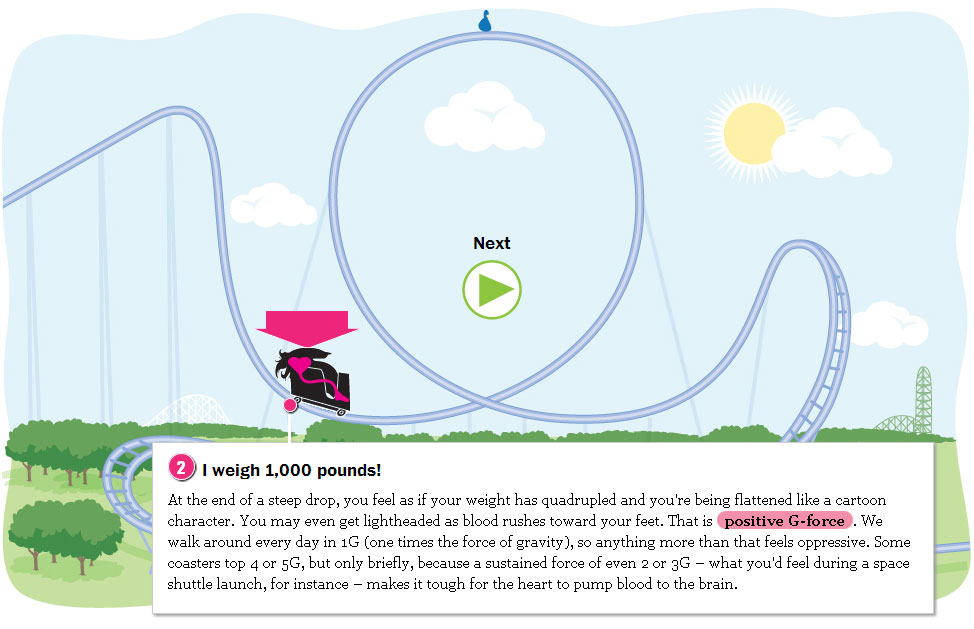

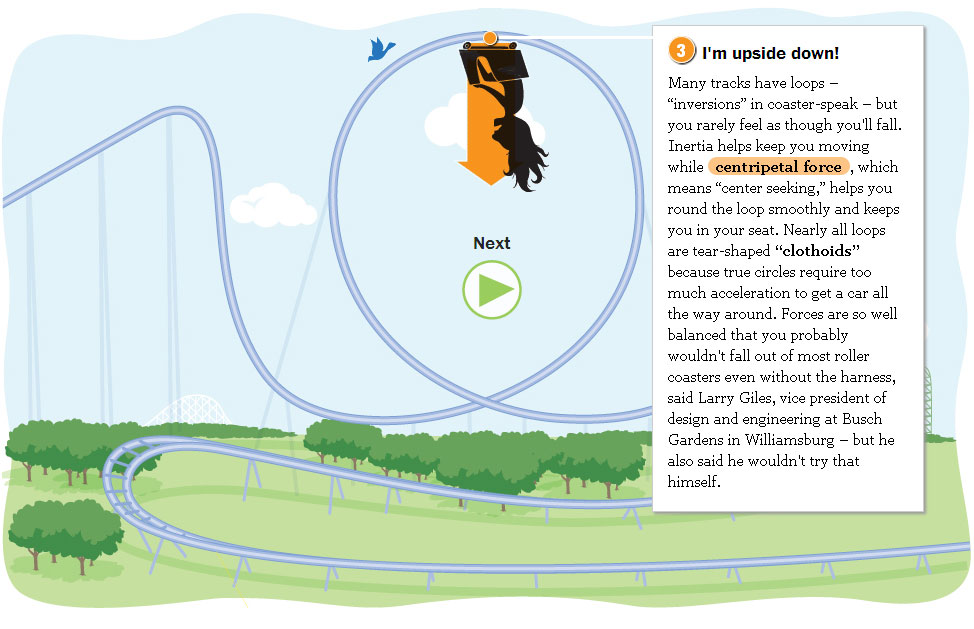

In this interactive graphic for the online version of the Washington Post, Berkowitz and Stanton explain the physics at play in roller-coaster design, showing why our bodies and brains respond to such rides as they do. Coasters may depend on a fair amount of illusion, as the authors suggest, but anyone who has ridden one can attest that the effects—whether fear, excitement, nausea, or joy—are very real.

Trends now and (maybe) later | ||||

Exposure. The less restrained you are, the faster and more dangerous the ride feels. Many types of coasters leave arms and legs to dangle in the breeze. |  Nostalgia. In the past, wooden coasters did not go upside down, but new ones use steel rails to create loops and barrel rolls while maintaining the rickety feel of wood. |  Surprise. On Verbolten at Busch Gardens in Williamsburg, magnets holding a section of track suddenly release and drop the car 16 feet into the middle of a dark, spooky “forest.” |  Personalization. Decker thinks riders in the not-too-distant future will be able to customize their experience by choosing a more or less intense trip on a given ride. |  Unique experiences. Riders may float in zero gravity for eight seconds on a coaster planned by “immersive experience” creator BRC Imagination Arts. |

View the interactive graphic.

Click through “Roller Coasters: Feeling Loopy,” and respond to the following questions.

Questions on Meaning and Strategy

Question

What do you take to be the PURPOSE of this interactive graphic? Do Berkowitz and Stanton seem interested mainly in informing readers, or do you detect some effort at persuasion? What details in the text lead you to your conclusion?

Question

What, according to the Berkowitz and Stanton, are some common effects of riding a roller coaster? What physical and psychological causes lead to the sensations that riders tend to experience?

Question

Explain the strategies the authors use to organize their cause-and-effect analysis. Why do you suppose they don’t simply follow chronological order?

Question

OTHER METHODS “Roller Coasters: Feeling Loopy” includes several short DEFINITIONS of terms from the field of physics. How effectively do the authors explain these terms for an AUDIENCE of nonspecialists? Do readers need to fully understand the scientific terminology to follow the explanations of cause and effect? Why do you think so?

Suggestions for Writing

Question

Roller coasters are big draws at amusement parks, and many enthusiasts try to ride as many as possible, even planning annual trips to experience the newest, most scream-worthy offerings. Although Berkowitz and Stanton’s SOURCES stress that the rides’ dangers are mostly illusory, several people have been killed or seriously injured in coaster accidents. Research the history of roller coasters and their changes in recent years. Based on your findings, write an essay arguing a position on the safety of roller coasters or similar thrill rides. Are they perfectly harmless, unnecessarily dangerous, or something in between? Support your argument with EVIDENCE from reliable sources and your own observations, taking care to document your sources as appropriate (see Chap. 3 on MLA documentation and the Appendix on APA documentation).

Question

CONNECTIONS In “Remembering my Childhood on the Continent of Africa” (Chap. 7), David Sedaris complains that growing up in North Carolina was “unspeakably dull” (par. 8), especially compared to his partner’s childhood in Africa. How do roller coasters — and the amusement parks they are found in — fit with Sedaris’s view of middle-class culture in the United States? CONTRAST, in particular, the American tendency to manufacture frightening experiences (such as thrill rides and horror movies) with circumstances in other parts of the world, where people are often exposed to real dangers and frightful situations.