National Geographic, From “The Pine Ridge Community Storytelling Project”

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

Founded in 1888, the National Geographic Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to science and education with a focus on archeology, natural history, and conservation. Its namesake magazine is especially well known for stunning photojournalism—such as that created by Aaron Huey, who has spent nearly a decade working with the residents of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota to document their lives. The reservation has a deep and troubled history. It was the site of the infamous Wounded Knee massacre, a surprise attack on December 29, 1890, in which least 145 Oglala men, women, and children were killed by US cavalry (some put the number closer to 300). Since then, the federal government has entered into and broken several treaties with the tribe; carved the faces of four US presidents on nearby Mount Rushmore, a site considered sacred by the Sioux; and attempted multiple times to outlaw native languages and customs. The reservation erupted with sometimes violent protest during the American Indian Movement of the 1970s, ultimately leading to an uneasy and frequently tested peace with the United States. Today, Pine Ridge is home to approximately three thousand Oglala Lakota Sioux and is one of the most impoverished counties in North America.

From the “Pine Ridge Community Storytelling Project”

Huey reported on conditions at Pine Ridge in a 2009 photo essay for National Geographic and was taken aback by the response. Although he had earned the trust of the Lakota in the years he had spent among them, he received dozens of letters from reservation students who took issue with his portrayals: His focus on poverty and desperation especially, they argued, stereotyped American Indians and failed to acknowledge the richness and complexity of their lives. The criticism inspired Huey to launch an innovative oral history project. In partnership with Cowbird—a Web-based interactive “storytelling tool” that incorporates multiple media, from photographs and text to audio and video—Huey and National Geographic provided the necessary equipment and invited the people of Pine Ridge to share their stories. The resulting collection of unedited oral histories, created by residents of the reservation themselves, debuted in August 2012; the project continues to grow with a goal of five hundred entries. We include five of them here.

“Unci Maka or Grandmother Earth”

By Marisa Snider

My fingers dig into the cool earth as I imagine this one plant growing, growing beyond belief. My fingers scrape against the dead grass left over from winter and I pluck out each one tenderly, so as not to pull away needed dirt. I see spring emerging as creatures stir. In Lakota culture, we look towards everything around us—plants, the trees, the seasons, the animals of the forest—as our relatives. Therefore, we never stop learning, even when others believe there is no lesson to be found. It is through my culture that I learned the importance of the natural world. I learned about the values of hardship and the fruits of labor. I learned about the value of failure, about how one can never learn from mistakes if they did not first fail at something.

I learned these rules of planting from my Aunt Jolene. My grandmother and mother used to joke that my aunt could put anything into the ground and a plant would miraculously grow two or three days later. I didn’t realize at first why they said this but one spring day, I understood. My Aunt Jolene was planting daffodils and I watched her from afar, curious. Her copper skin glimmered in the sunshine and her crow black hair was pulled into a long, intricate braid. She looked at the ground, tenderly pulling away the unwanted grass and made a small hole for the flowers. There was a genuine and peaceful look that never left her eyes. She turned around suddenly and noticed me standing awkwardly to the side, my fingers twiddling nervously. She motioned towards me with one finger and pointed at the small pile of dirt that had collected at her feet. She smiled and grabbed a small, limpid flower that was barely alive. Its leaves were edged in brown and its slender green stem looked ready to break. My Aunt placed it into the ground.

“No! That plant won’t grow!” I objected.

But she smiled.

I was young and naïve. I had belief that if something went wrong, I had to give up because what was the point in trying again when I would just fail? It was through my Aunt’s small and genuine gesture and her advice that I came to the realization of moving forward. That was all I could do in life was try my hardest, work until I could not work anymore, and then on the brink of exhaustion instead of giving up I had to keep going. If my hard work went to waste than it was only a matter of how strong I was about trying again. How determined I was to keep working towards my goal.

To this day, I still remember my shock when that daffodil grew to be the biggest out of all of them.

“First Racist I Ever Encountered”

By Tom Swift Bird

“You’re ugly.” A small girl, perhaps three years old, tells me as I walk past a rusty swing set.

“Why?” I ask, genuinely curious.

“Your skin is brown.”She responds.

It’s true. Though my mom is of Netherlandic heritage, I could never be mistaken for anything other than Lakota on the basis of looks. My father’s leather skin tone out raced my mother’s in the genetic cauldron. I had never thought of my skin as a thing of shame. We were at a church bible camp. I wondered if that brown skin was why the church considered me a “bad kid”? A lot in the world made sense for the first time.

I had to try hard not to laugh. I always got in trouble when I laughed. Authorities, preachers, school principles, those intoxicated by their own insignificant power, hear a challenge in laughter. But it seemed so stupid. It still does. The misplaced importance some place on the pigment of skin.

“Becoming a Lakota Woman”

By Monique M. Apple

Surrounded by my Unci (Grandmother), Ina (Mother), Tunwin (Aunts), and Scepansi (Female Cousins) inside my tipi. Ina dressing me in my finest traditional regalia, braiding my hair in two braids, painting my part red, fastening my eagle plume to my hair. It's a hot, dry mid-summers day, no airconditioner in that tipi. My mouth is dry and my stomach is growling, yet I sit quietly as I am being prepared to go through my Isnati Awica Lowanpi (Lakota Womanhood Ceremony).

Sitting on a buffalo robe and a bed of sage, my Unci told me about why my hair was being braided in two—“This is how you will wear your hair, braids in front as a woman does, not behind as when you were a little girl.”

Crosslegged I sat on that buffalo robe and bed of sage. My Unci told me—“Fold your legs to the side. This is how you will sit as a woman, not crossed like when you were a little girl.”

Buffalo skull before me, my Unci paints my face—“You will wear this red earth paint. Now the Tunkasila will know you, and that you have gone through this ceremony, and when you dance you will wear this paint and the Tunkasila will know who you are.”

I now sit with my legs to the side, braids in the front over my chest, buffalo skull before me. My Unci paints a red line down the center of the skull and told me—“This is the path you will follow, the good red road. You might stray off of it, but the Tunkasila will be there with you watching over you and guide you back to it. You will have a big house and big pots and pans.”

Unci handed me a small sea shell, and told me—“You will use this to feed the spirits.” She spoke of maintaining my virtuousness, and how to conduct myself as a woman, and to always be productive.

This would be one of the first time in years since the Lakota ceremonies were outlawed by the federal government that a young Lakota girl would be able to go through her Womanhood ceremony without fear of persecution. Today, many Lakota girls have been able to have Womanhood ceremonies done for them, but not as many as there should be. I am so grateful that my Unci and my Ina and Tunwin were able to do this for me, and I have in turn been able to do this for my oldest daughter.

Wakanyeja Lena Ki Lakol Wicohan Skil Glus Mauni Pi Kte—“May these children walk, holding tight to their Lakota Ways and not let go.”

“I See Spirits”

By Leon Matthews

You can hear many ghost stories across the Pine Ridge Reservation, but like seeing a ghost or spirit you have to open your eyes and ears to experience them. I have a couple of stories I think about and how I deal with the spirit realm today just in case you find yourself walking down a dark Rez road. When I was young I thought I would be a macho guy or warrior and walk a mile to my home. Yeah to city folk that seems to be an easy task because it is close to ten city blocks. I thought of this story and since we have technology I will let you hear it in my own words…

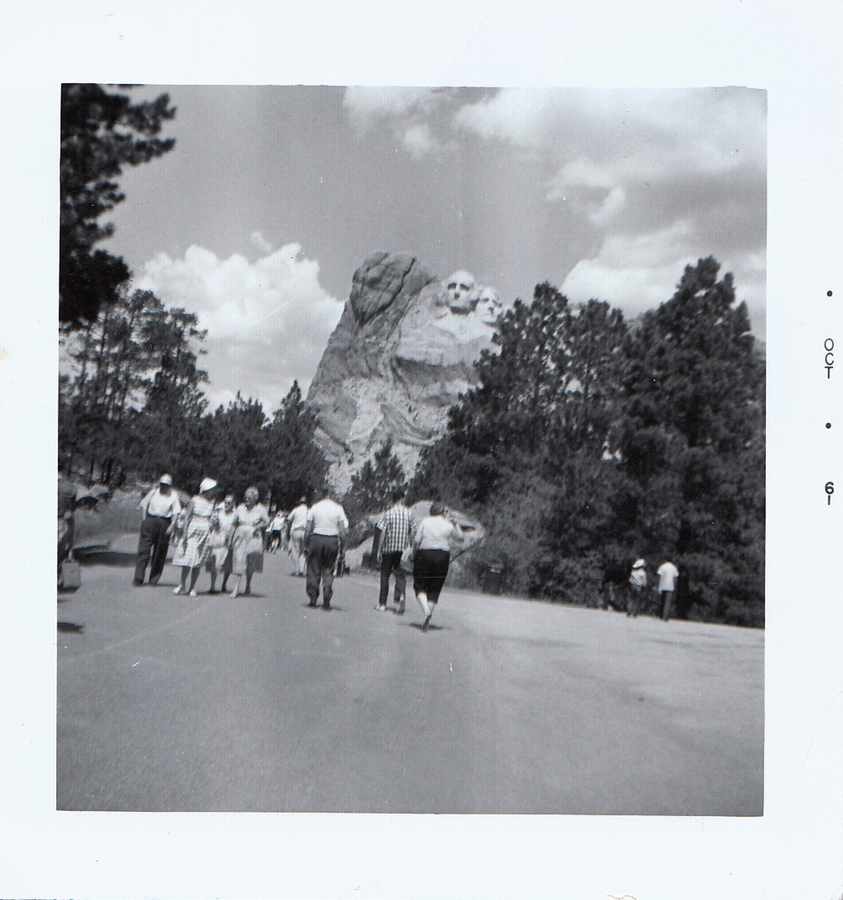

“Faces I Do Not Worship”

By Marisa Snyder

This photograph represents struggle, hardship. 3,308 individual voices screaming out against the betrayal, the consumerism that takes place within their own home.

If someone were to ask about what Mount Rushmore was to me, I'd say it.

They are faces I do not worship.

Examine each of the stories from the “Pine Ridge Community Storytelling Project,” and respond to the following questions.

Questions on Meaning and Strategy

Question

What word or words would you use to characterize the TONE of these stories? Overall, how do the residents of Pine Ridge seem to want others to understand them?

Question

Although they are personal narratives, most of these oral histories address political and social issues. Create a list of the issues the speakers and writers touch on, whether directly or indirectly. Do you detect any underlying theme or themes in the collection?

Question

Point to a few of the FIGURES OF SPEECH used by the storytellers. Which ones strike you as particularly effective, and why?

Question

OTHER METHODS Consider how the project participants use multimedia to enhance their DESCRIPTIONS of life on the Pine Ridge Reservation. What do the images and sounds contribute to the narratives? What would be lost without them?

Suggestions for Writing

Question

Open a free “Nomad” account at Cowbird (cowbird.com), and create your own multimedia story. You might share a significant event from your life, invent a tale with a clear moral, air a complaint, express a hope, or argue a point. Whatever focus you choose, be sure to select a cover photograph that illustrates some aspect of your story, to keep your narrative brief, and to give your creation a compelling title and informative keyword so that others can find it easily.

Question

CONNECTIONS In “Superman and Me” (Part Three), Sherman Alexie also writes about life on an Indian reservation. What ASSUMPTIONS and concerns do he and the Pine Ridge storytellers seem to share? In what ways do their perspectives differ, and why? In an essay, imagine how Marisa Snider, Tom Swift Bird, Monique M. Apple, or Leon Matthews might respond to Alexie’s THESIS. Do they seem to think their lives need saving? Why, or why not? What solutions to their problems might they propose beyond education?