11.2 Parenthood

I have never felt the joy that my daughter brings me when I wake up and see her . . . when you are laying there and . . . and feel this little hand tapping on your hand . . . that has been the most joyful thing I ever have experienced. . . . I’ve never been able to get that type of joy anywhere else.

(quoted in Palkovitz, 2002, p. 96)

Setting the Context: More Parenting Possibilities, Fewer Children

Poll parents and you will hear similar comments: “The love and joy you have with children is impossible to describe.” The great benefit of the 1960s lifestyle revolution is that more people than ever can participate in this life-

At the same time, people have freedom not to be parents—

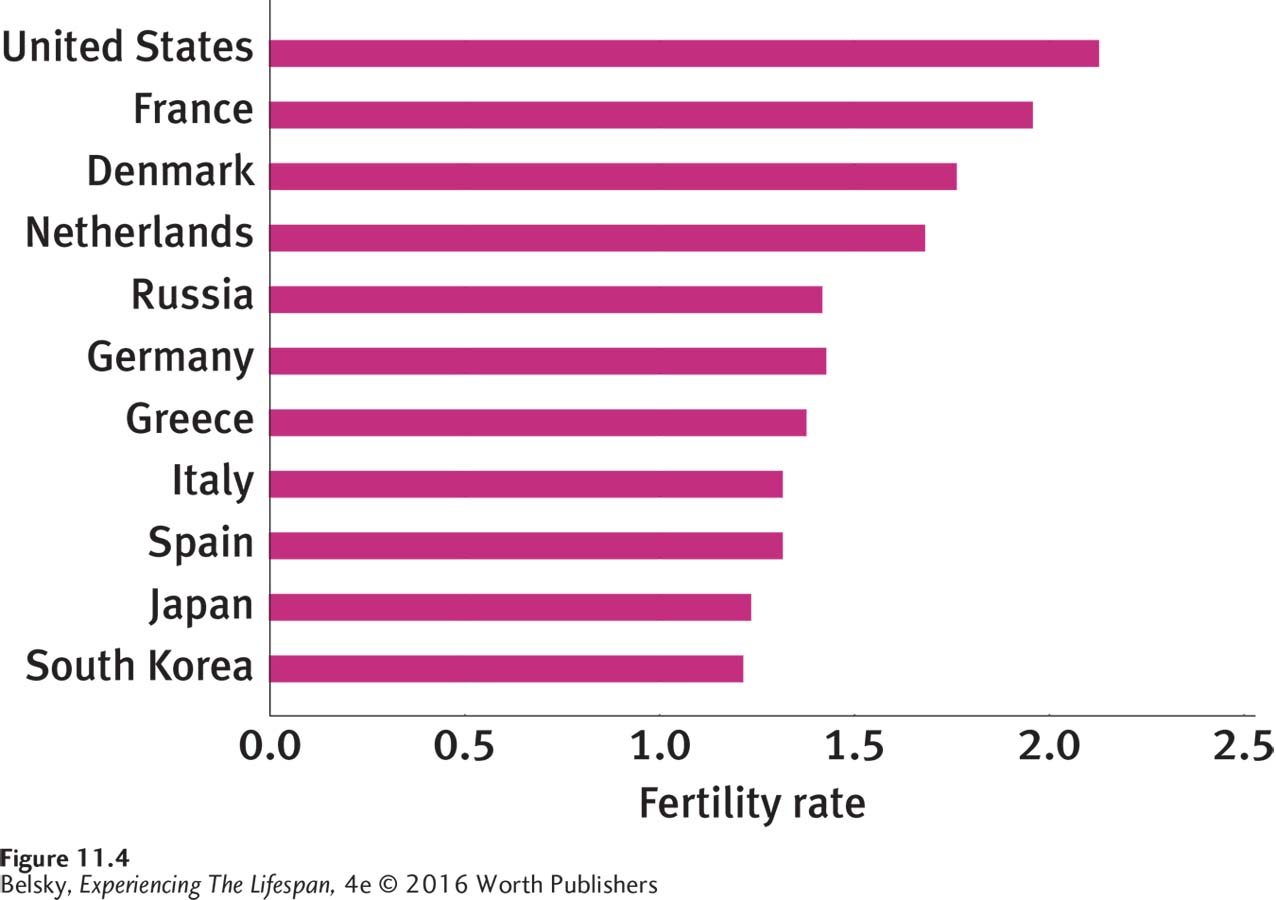

Why has fertility dropped well below the level to keep the population constant (2.1 births) in every European nation, as well as in Russia and Asia? (See Li and others, 2011.) A major cause, in Europe, lies in the stalled progress people are making toward adulthood. Remember from Chapter 10 that, in Italy, Spain, and Greece, most twenty-

Are people who decide not to have children more materialistic and narcissistic than their peers? The answer is no! (See Gerson, Posner, & Morris, 1991.) Childless adults—

The Transition to Parenthood

To see how becoming parents affects a marriage, researchers conduct longitudinal studies, selecting couples when the wife is pregnant, then tracking those families for a few years after the baby’s birth. Understanding that parenthood arrives via many routes, social scientists have explored how having a child affects the bond between gay partners (Goldberg, Smith, & Kashy, 2010) and cohabiting couples, too (Kamp Dush and others, 2014). Here are the conclusions of these studies exploring the transition to parenthood:

Parenthood makes couples less intimate and happy. Look back to the infancy chapters—

especially the discussion of infant sleep in Chapter 3—and you will immediately see why a baby’s birth is apt to change passion and intimacy for the worse. In fact, look at any couple struggling with an infant at your local restaurant and you will understand why researchers find that feelings about one’s partner shift from lover to “fellow worker” after the baby arrives (Belsky, Lang, & Rovine, 1985).

341

This tendency to get less satisfied (and certainly less romantic) applies equally to heterosexual couples and gay couples who are adopting a child (Goldberg, Smith, & Kashy, 2014; Tornello & Patterson, 2012). Still, in one tantalizing U.S. study, heterosexual men in cohabiting relationships felt especially hemmed in and unhappy after a child’s arrived (Kamp Dush and others, 2014). We need to be cautious about interpreting these results, because recall that unmarried U.S. cohabiting couples are apt to be less economically secure. However, these findings clearly imply that—

If the couple is heterosexual, parenthood produces more traditional (and potentially conflict-

ridden) marital roles. Among heterosexual partners, having children accentuates traditional gender roles (Katz- Wise, Priess, & Hyde, 2010). Even when the man and woman have been sharing the household tasks fairly equally, women often take over most of the housework and child care after the baby arrives. Often this occurs because, as you will see later in this chapter, after having children, a woman may leave her job or reduce her hours at work. However, even when both spouses work full time, mothers tend to do more of the diaper changing and household chores than dads (Bryan, 2013). This change can provoke conflicts centered on marital equity, or feelings of unfairness: Women get angry with men for not doing their share around the house (Dew & Wilcox, 2011; Feeney and others, 2001).

What compounds the sense of over-

These examples show exactly why we can’t expect having a child to draw people closer together, whether the partners are gay or heterosexual, married or not. (Here the most relevant saying may be, “Three is a crowd.”) However, after becoming parents, one classic study revealed that about 1 in 3 spouses did report more love for a husband or wife (Belsky & Rovine, 1990).

To predict which relationships are prone to develop serious problems, survive, or flourish, we need to adopt a developmental systems approach—

The pre-

Now that we’ve looked at its impact on the couple, let’s turn to parenthood from mothers’ and fathers’ points of view.

Exploring Motherhood

I’ve already talked about the love that mothers feel for their children, especially in the infancy section of this book. Drawing on the previous section, children are our prime vehicles for expressing compassion. They embody the joy we get from sacrificing for a beloved person’s well-

342

Still, the downside of this 24/7 sacrifice—

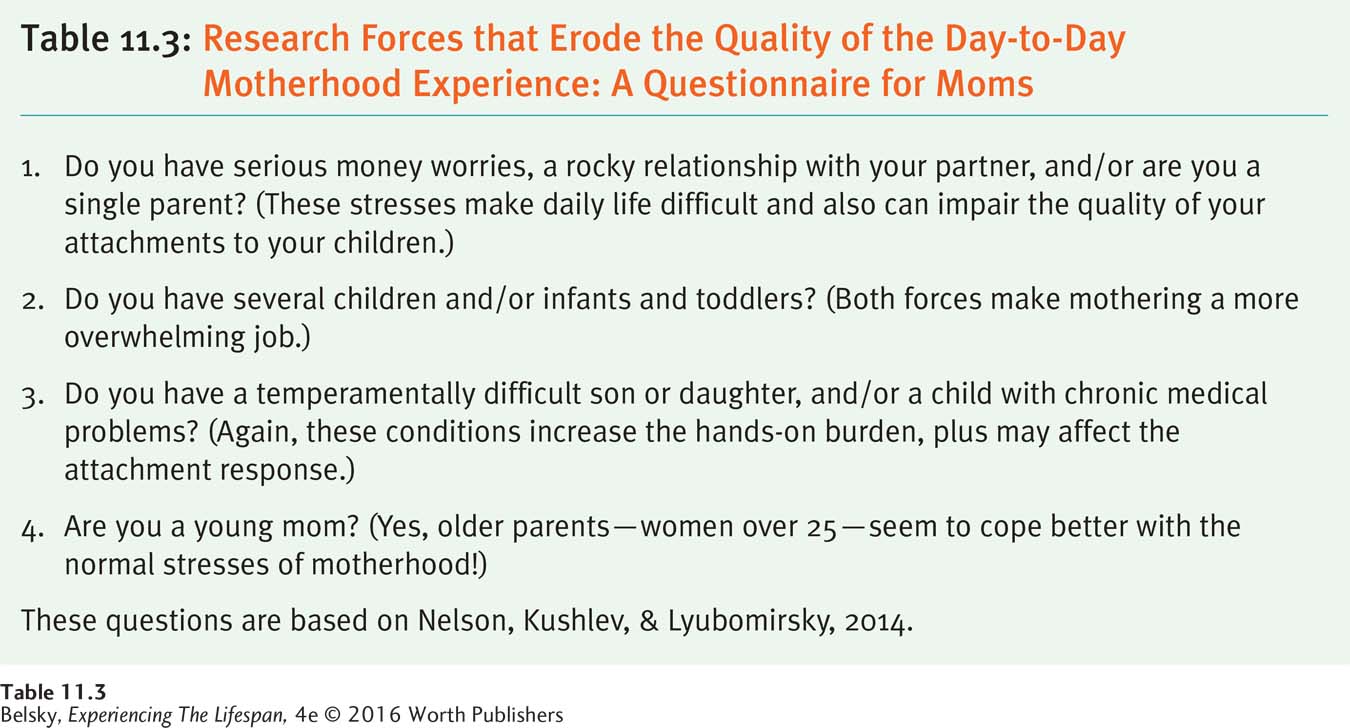

Table 11.3 offers a research-

The Inner Motherhood Experience

One downside of motherhood, women in this U.S. national poll reported, is that it destroys cherished fantasies people have about how they expected to behave (Genevie & Margolies, 1987). One in two mothers admitted that they had trouble controlling their temper. Disobedience, disrespect, and even typical behaviors such as a child’s whining might provoke reactions bordering on rage. When confronted with real-

Given the bidirectional quality of the parent–

Lee Ann has been my godsend. My other two have given me so many problems and are rude and disrespectful. Not Lee Ann. . . . I disciplined her in the same way . . . except that she seemed to require less of it. Usually she just seemed to do the right thing. She is . . . my chance for supreme success after two devastating failures.

(quoted in Genevie & Margolies, 1987, pp. 220–

These emotions destroy another motherhood ideal: Mothers love all their children equally. Many women in this study did admit they had favorites. Typically, a favorite child was “easy” and successful in the wider world. However, most important, again, was the attachment relationship, the feeling of being totally loved by a particular child. As one woman reported:

343

There will always be a special closeness with Darrell. He likes to test my word. . . . There are times he makes me feel like pulling my hair out. . . . But when he comes to “talk” to mom that’s an important feeling to me.

(quoted in Genevie & Margolies, 1987, p. 248)

Not only does the experience of motherhood vary dramatically from child to child, it shifts from minute to minute and day to day:

Good days are getting hugs and kisses and hearing “I love you.” The bad days are hearing “you are not my friend.” Good days are not knowing the color of the refrigerator because of the paintings and drawings all over it. Bad days are seeing a new drawing on a just painted wall.

(quoted in Genevie & Margolies, 1987, p. 412)

In sum, motherhood is wonderful and terrible. It evokes the most uplifting emotions and offers painful insights into the self. Now that we understand the individual situations that make motherhood more challenging, let’s explore how the wider world can amplify mothers’ distress.

Expectations and Motherhood Stress

Society provides women with an airbrushed view of motherhood—

What compounds the problem are unrealistic performance pressures. Good children, as you saw in the above quotation, make a mother feel competent. “Difficult” children can make a woman feel like a failure. Despite all we know about the crucial role of genetics, peers, and the wider society in affecting development, mothers still bear the responsibility for the way their children turn out (Coontz, 1992; Crittenden, 2001; Douglas & Michaels, 2004; Garey & Arendell, 2001).

Single mothers face the most intense pressures as they struggle with financial hurdles, working full time, plus trying to fulfill the “blissful” mom ideal. But every woman is subject to the intense pressures of contemporary motherhood: be patient; cram in reading; provide enriching lessons; produce a perfect child. To what degree is the so-

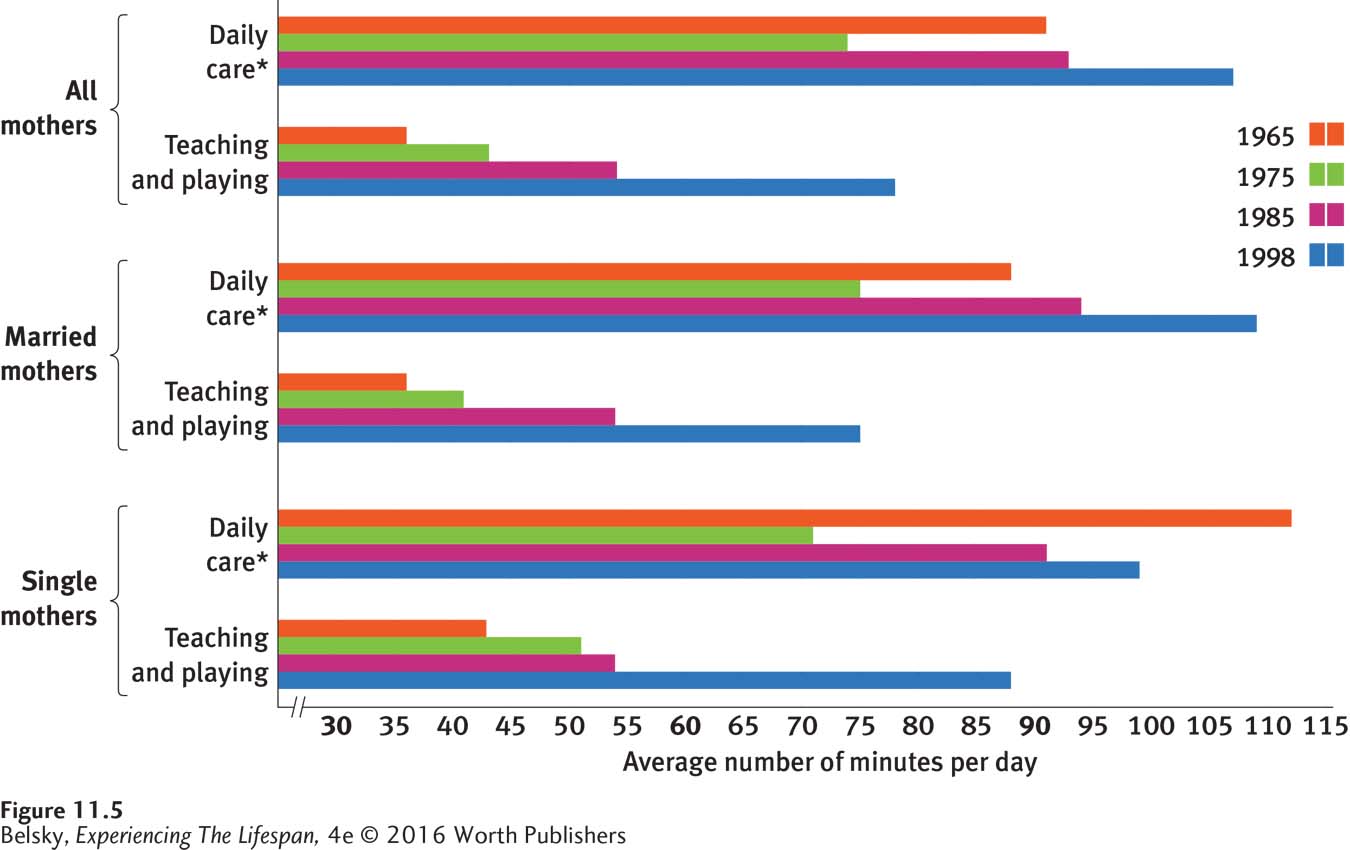

I’m sure you’ve heard that today’s moms are not giving children the same attention as in “the good old days.” Figure 11.5, below, proves this “obvious” assumption is wrong. Notice that twenty-

344

Where are fathers in his picture? Earlier, when I talked about equity issues during the transition to parenthood, I might have given the impression that contemporary dads are slacking off. Not so! Today’s fathers are often making valiant efforts to be involved parents, too.

Exploring Fatherhood

When women first entered the workforce in large numbers in the 1970s, it became a badge of honor for fathers, in addition to fulfilling the traditional breadwinner role, to change the diapers and to be deeply involved in caring for their children. From Slovakia (Švab & Humer, 2013) to Sweden (Björk, 2013) and from Australia (Thompson, Lee, & Adams, 2013) to Japan and the United States (Ito & Izumi-

The lack of guidelines leaves fathers with contradictory demands. “Should I be strict, or nurturing, sensitive, or strong? Should I work full time to feed my family or reduce my hours at work and stay home to feed my child?” (Björk, 2013; McGill, 2014; Mooney and others, 2013). Given that there may be no “right” way to be a father, how do men carry out their role?

How Fathers Act

As you would expect from the principle that they should be good sex-

345

How much hands-

Furthermore, these studies don’t tell us which parent is taking bottom-

Based on the earlier discussion of society’s expectations, it seems likely that mothers typically continue to take bottom-

In sum, although today’s fathers are doing far more hands-

Variations in Fathers’ Involvement

If you look at the fathers you know, however, you will be struck by the variations in this profile. There are divorced men who never see their children, and traditional “I never touch a diaper” dads; there are househusbands who assume primary caregiving responsibilities, and men who take sole care of the kids. What statistical forces predict how involved a given father is likely to be?

In two-

Dads in gay relationships are apt to be full caregiving partners (Golombok and others, 2014), as are married heterosexual men who have good relationships with their mates (Perry & Langley, 2013)—giving us another reason why male/female cohabiting parents, at least in the United States, seem most at risk. Liberal family-

This last consideration brings up the greatest barrier that keeps fathers from being completely involved: the need to be the primary breadwinner. For all our talk about equal family roles, supporting a family is at the core of many men’s identities as adults. Men—

346

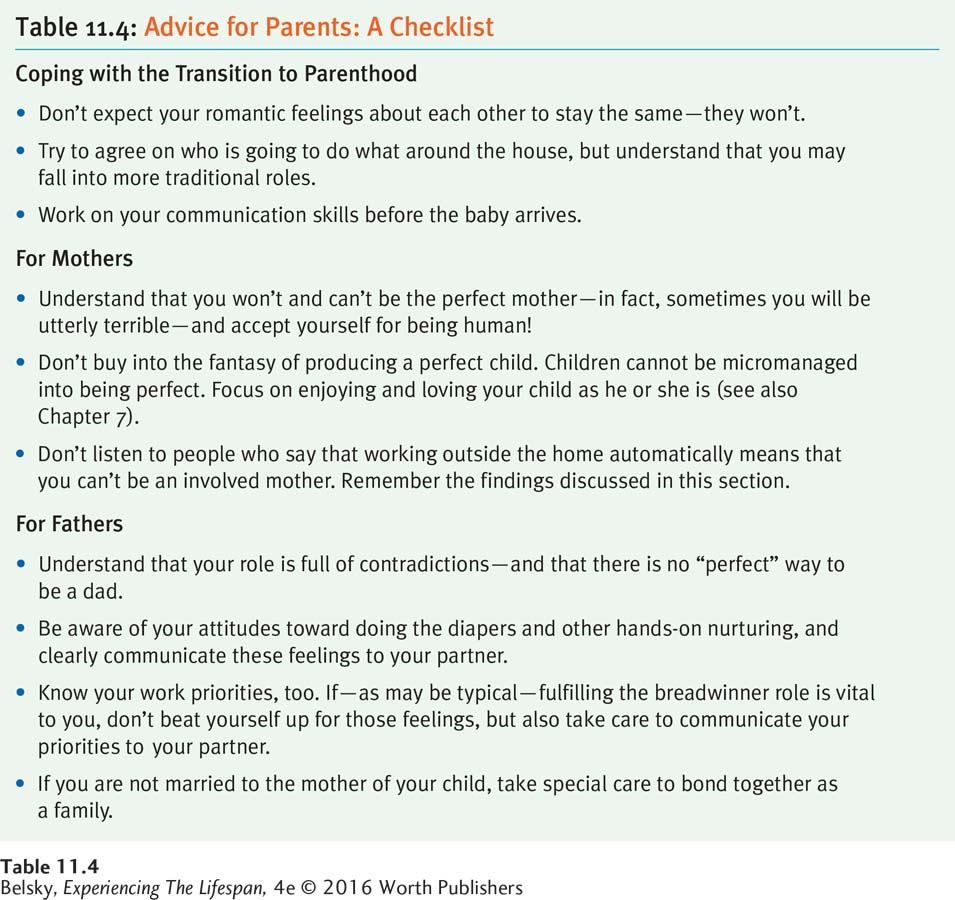

How are things really changing with regard to work for women and men? First, let’s sum up these section messages in Table 11.4, then explore this question as we turn to the third vital adult role: work.

Tying It All Together

Question 11.7

Jenna and Charlie, a married couple, are expecting their first child. According to the research, how might their marital satisfaction change after having the baby? How might their happiness change if they were a same-

Statistically speaking, you would expect this couple’s marital satisfaction to decline (same would be true if this couple were gay). If Jenna and Charlie were not married, Charlie might be especially dissatisfied after Jenna gave birth.

Question 11.8

Akisha, a new mother, is feeling unexpectedly stressed and unhappy. She and other mothers might cope better if they experienced which two of the following?

Got a less rosy, more accurate picture about motherhood from the media

Had more experts giving them parenting advice

Had less pressure placed on them from the outside world to “be perfect”

a and c

Question 11.9

Your grandmother is complaining that children today don’t get the attention from their parents that they got in the “good old days.” How should you respond, based on this chapter? Be specific with regard to both mothers and fathers.

Tell grandma that’s not true! Parents are spending more time with their children than in the past. Moms do far more hands-

Question 11.10

Construct a questionnaire to predict how heavily involved in child care a particular man is likely to be, and give it to some fathers you know.

My questions (but you can think of others!): (1) Do you think child care is basically a woman’s job, or should couples share this responsibility? (2) Are females basically superior at child-