11.3 Work

347

What is work like in the Western world, and how can you construct a fulfilling career life?

Setting the Context: The Changing Landscape of Work

Let’s begin our discussion by spelling out three changes in the developed-

More career (and job) changes. Work used to have a structured path. Right after high school or college, men found a job and often stayed in that same organization until they retired (Super, 1957). This traditional stable career is now atypical. People move from job to job, or change direction, starting new careers as they travel through life. Today adults experience a shifting work pattern called boundaryless careers (DeFillippi & Arthur, 1994). Our less-

defined career path is mirrored by less definition to work itself. The disappearing barrier between work and family. Work life used to be separate from home life (Davies & Frink, 2014). You went to your job from 9 to 5 on Monday through Friday and spent weekends and evenings with your children and spouse. Today, with people working flexible hours, nonstandard work hours have become common (Cappelli & Keller, 2013). More important, technology has moved work out of the office to permeate family life (Perrone-

McGovern and others, 2014).

The benefit of the on-

Longer working hours (and more job insecurity). Actually it’s a myth that the U.S. work ethic has diminished and that Americans worked longer hours in the “good old days.” Educated men (and, of course, women) in the United States are putting in more hours per week at their full-

time jobs than their parents or grandparents did.

Consider findings from the National Survey of the Changing Workforce (NSCW), a U.S. poll that regularly monitors the hours that workers work (Families and Work Institute, 2009). The survey showed that by the beginning of the twenty-

In the European Union, governments limit overwork by requiring member states to keep work time to less than 48 hours per week. Japan, with its routine 50-

One force propelling the drive to work longer hours is job insecurity. Especially since the Great Recession of 2008, people know that unless they perform well, they are at risk of getting fired. So one co-

Clearly these kinds of treadmill pressures limit our joy in a job. What specifically makes for career happiness and success?

348

Exploring Career Happiness (and Success)

Suppose you wanted to predict which high school classmates would be successful at their careers. It’s a no-

Clues come from that regular University of Michigan poll exploring health behaviors and attitudes in different cohorts of teens (discussed in Chapter 9). At their first evaluation, sampling high schoolers in 1979, the researchers measured what they called “core self-

Why do attitudes such as optimism and self-

Once at work, people who have high self-

Other personality traits that go along with work success are having the emotion-

Are you blessed to see your work as a life calling? As I can tell you, there is no greater gratification than finding a career that you feel called to do. We might think that living a calling causes us to be committed to our work. One longitudinal study suggested the reverse. In a way similar to marriage, researchers found developing this feeling grew out of time spent committed to a career (Duffy and others, 2014). So, the reason I see writing textbooks as my life calling (it’s beshert!) came from years spent making writing the center of my life.

But seeing writing textbooks as my calling involved more than being committed to working hard. I lucked into a career that matched my personality!

Strategy 1: Match Career to Your Personality

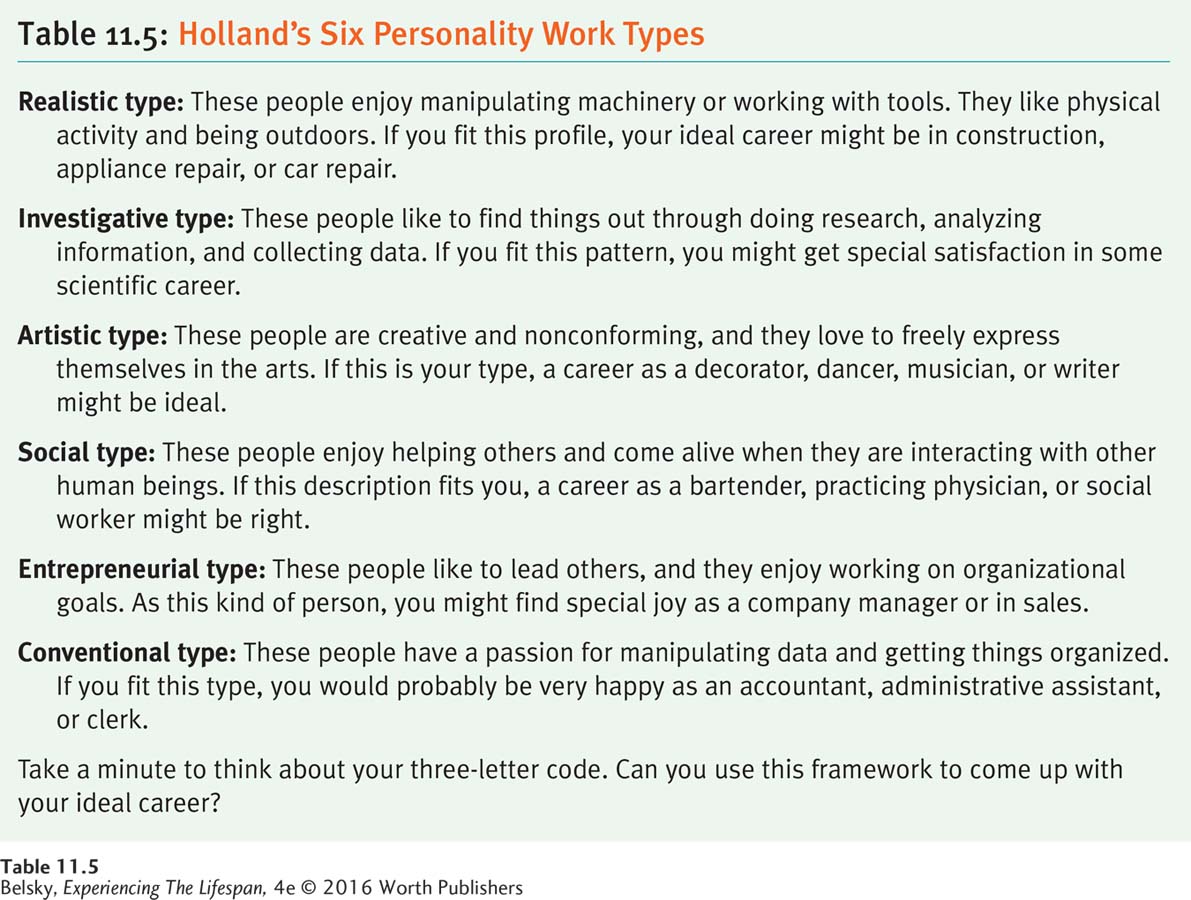

According to John Holland’s (1997) classic theory, the key to work happiness is to find my kind of personality–

To promote this fit, Holland classifies six personality types, described in Table 11.5, and fits them to occupations. Based on their answers to items on a career inventory, people get a three-

349

Still, even when people have found work that fits their personality, there is no guarantee that they will be happy at a job. What if your gallery director job involves mountains of paperwork and little time exercising your creative or social skills? Suppose your gallery is in financial trouble, and you have a micromanaging owner in charge? To find work happiness, it’s vital to consider the actual workplace too.

Strategy 2: Find an Optimal Workplace

What constitutes an ideal job situation? Workers agree that jobs should give us autonomy to exercise our creativity. We want caring colleagues, and organizations that are sensitive to our needs (Fossen & Vredenburgh, 2014). Remember from Chapter 7 that these same qualities—

Extrinsic career rewards, or external reinforcers, such as salary, can also be crucial, depending on a person’s situation. For instance, one longitudinal study showed intrinsic career rewards become less vital to work satisfaction as people (particularly men) moved through their twenties and had families—

350

Remember from Chapter 10 that flow states require that our skills match the demands of a given task. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that one poisonous job-

This brings up the topic of family–

How do women and men behave when faced with the competing pulls of family and career? For answers, let’s end this chapter with a status report on gender and work.

Hot in Developmental Science: A Final Status Report on Men, Women, and Work

Today, men say they are searching for well-

With women now more likely than men to graduate from college in many nations, we might expect females to overtake males in their careers. Still, for the reasons below, traditional gender attitudes are alive and well in the world of work.

Women (especially when they are married) have more erratic, less continuous “careers” than men. For one thing, husbands are more apt to work continuously, while wives move in and out of the workforce to provide family care (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010). The first exit may occur early in adulthood. As one U.S. longitudinal survey showed, a pregnant woman has three times higher odds of leaving work than her counterpart who is not planning to have a child (Shafer, 2011). Another may happen in midlife, when she takes off time to care for her elderly parents as they become physically frail (see the next chapter for more information).

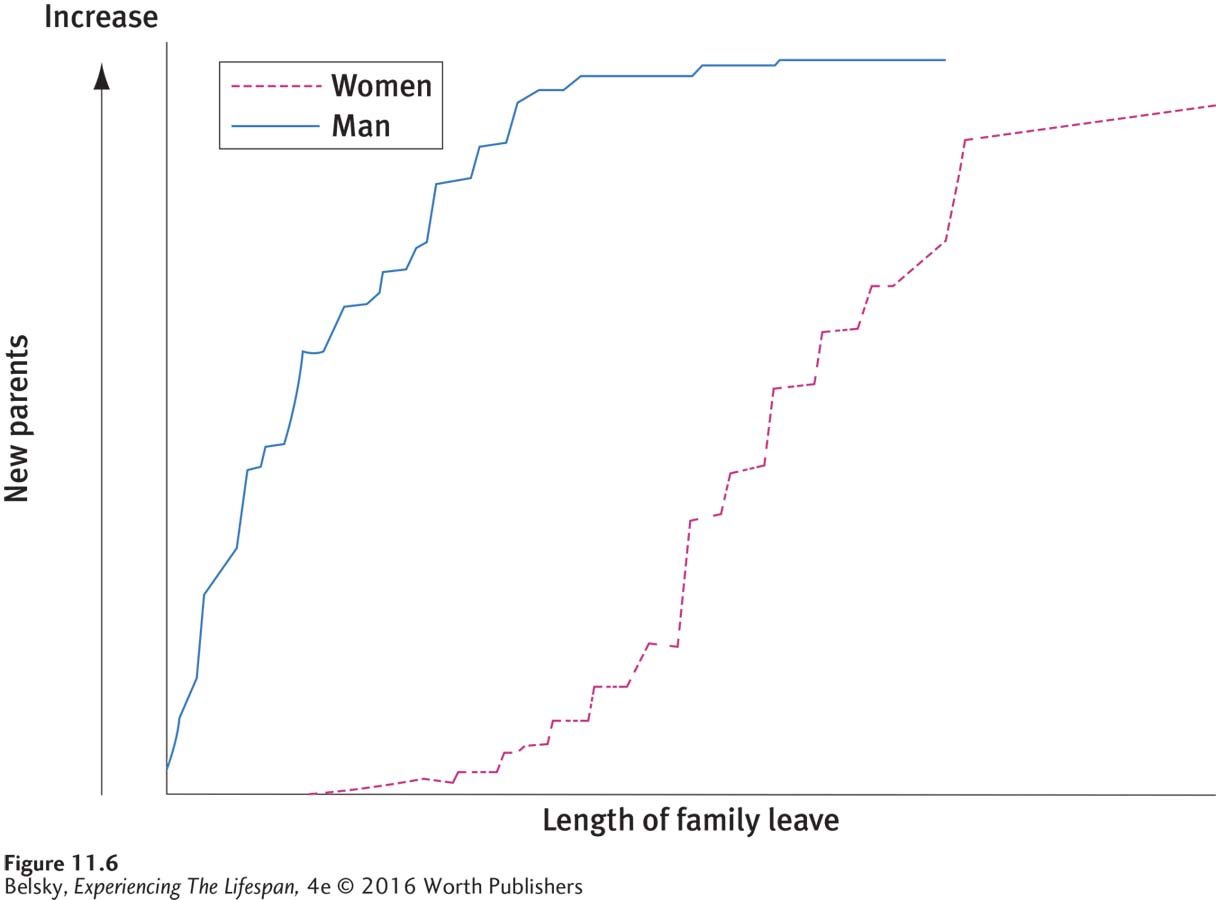

In places like Japan, which provide minimal government support for family care, an astonishing 3 out of 4 married working women exits the labor force after having a child (Fuwa, 2014). But in Sweden, a nation that encourages gender equality and offers both sexes equally lavish family leave, after becoming parents, women also become less committed to their jobs (Evertsson, 2014). Swedish leave-

351

Women earn less than men, and jobs are gender defined. This difference may be partly due to economics. Men who work full time earn more than their female counterparts. In the United States in 2011, for instance, women’s wages on average stood at 82.4 percent of men’s salaries when both genders worked full time (U.S. Department of Labor, 2011).

We might think the cause is occupational segregation, meaning that work is divided into classically “male” (higher paying) and “female” (lower paying) jobs (Charles, 1992; Cohen, 2004; Reskin, 1993). Female-

Society prioritizes salaries for fathers and expects married men to out-

earn their wives. Although this wage disparity is partly due to women’s less continuous careers, societal attitudes also are involved. In the United States, fatherhood is associated with a wage rise of 4 percent (Killewald, 2013). The interesting fact that stepfathers and cohabiting men don’t show this statistical income jump suggests that employers implicitly believe that men deserve to bring home more bacon when they are married and father a child.

Actually, the fact that (at least in the United States) people don’t feel it’s quite kosher for married women to bring home most of the bacon is supported by other evidence: Researchers gave undergraduates fictitious scenarios in which they were asked to rate the qualifications of a person for promotion. When they arranged to have everything be equal, but made the main wage earner a wife (saying her salary was $100,000 in a household reporting an income of $150,000), both males and females rated this person as basically less qualified to advance (Triana, 2011).

There is even a sexual counterpart to this connection to traditional gender roles. When researchers studied prescription-

352

The bottom line is that the women’s movement seems to have changed society (and our inner sex-

Tying It All Together

Question 11.11

Michael, age 30, has just begun his career. Compared to his grandfather, who entered his career 50 years ago, what two predictions can you make for Michael?

Michael will change jobs more often than his grandpa.

Michael will work fewer hours per week than his grandpa.

Michael will have less traditional work hours than his grandpa.

a and c

Question 11.12

Vanessa, a bubbly, outgoing 30-

Vanessa’s isolated work environment doesn’t fit her sociable personality. She needs ample chances to interact with people during the day.

Question 11.13

Malia and her husband work full time. Statistically speaking, you can make two of the following predictions:

Malia will probably take more time off from work for family caregiving.

Malia will probably earn less than her spouse.

Malia will probably be less well-

educated than her spouse.

a and b

Question 11.14

According to this chapter, with regard to family and work, traditional gender roles still exist/no longer exist.

still exist