12.2 Exploring Personality (and Well-

Actually, we have contradictory views about how our personality changes during adulthood. One is that we don’t change: “If Calista is irascible in college, she will be bitter in the nursing home.” Another is that entering new life stages, or having life-

Do people stay the same or grow as the years pass? As we see now, by looking at the research, both ideas are true!

Tracking the Big Five

Today, the main way psychologists measure personality is by ranking people according to five basic temperamental qualities. As you read this list, take a minute to think of where you stand on these largely genetically determined dimensions, which Paul Costa and Robert McCrae have named the Big Five traits:

Neuroticism refers to our general tendency toward mental health versus psychological disturbance. Are you resilient, stable, and well-

adjusted, someone who bounces back after setbacks; or hostile, high- strung, hysterical, and impulsive, a person who others might label as psychologically disturbed? (Children with serious externalizing and internalizing tendencies, for instance, would rank high on neuroticism.) 359

Extraversion describes outgoing attitudes, such as warmth, gregariousness, activity, and assertion. Are you sociable, friendly, a real “people person,” someone who thrives on meeting new friends and going to parties, or are you most comfortable curling up alone with a good book? Do you get antsy when you are by yourself, thinking “I’ve got to get out and be with people,” or do you prefer living a reflective, solitary life?

Openness to experience refers to our passion to seek out new experiences. Do you adore traveling the world, adopting different perspectives, having people shake up your preconceived ideas? Do you believe life should be a continual adventure and relish getting out of your comfort zone? Or are you cautious, rigid, risk averse, and comfortable mainly with what you already know?

Conscientiousness describes having the kind of efficacious, worker personality described in Chapters 10 and 11. Are you hardworking, self-

disciplined, and reliable, someone others count on to take on demanding jobs and get things done? Or are you erratic and irresponsible, prone to renege on obligations and forget appointments, a person your friends and co- workers really can’t trust?  Look at these exuberant women enjoying themselves at a party and you will understand why extroverts are generally happy (and also why simply being around a “people person” makes us feel more upbeat). How would you rank yourself on extraversion, and each of the other Big Five traits I just described?bikeriderlondon/Shutterstock

Look at these exuberant women enjoying themselves at a party and you will understand why extroverts are generally happy (and also why simply being around a “people person” makes us feel more upbeat). How would you rank yourself on extraversion, and each of the other Big Five traits I just described?bikeriderlondon/ShutterstockAgreeableness has to do with kindness, empathy, and the ability to compromise. Are you pleasant, loving, and easy to get along with; or stubborn, hot-

tempered, someone who continually seems offended and gets into fights? (Agreeable people, for instance, have secure attachment styles.)

Hundreds of studies show that our Big Five rankings have consequences for our lives. Because they are upbeat and happy, extraverts have more fulfilling relationships (Butkovic, Brkovic, & Bratko, 2011; Cox and others, 2010). People high on neuroticism, being impulsive and depressed, are more apt to suffer from chronic diseases (Sutin and others, 2013). Passionate to expand their horizons, adults high on openness are set up to grow emotionally (Lilgendahl, Helson, & John, 2013) and stay cognitively sharp (von Stumm, 2013) as the years pass. One longitudinal study even suggested that openness to experience and conscientiousness might help protect us against developing Alzheimer’s disease (Duberstein and others, 2011).

Without neglecting the role of each Big Five trait in constructing a successful life, researchers are particularly interested in the impact of conscientiousness as we travel from childhood to old age. So let’s pause to look at the lifespan path of this personality dimension in more depth. (Unless otherwise noted, these findings come from Shanahan and others, 2014; Reiss, Eccles, & Nielson, 2014.)

Hot in Developmental Science: Tracking the Fate of C (Conscientiousness)

The childhood quality that defines conscientiousness is good executive functions—meaning being able to think through your actions and modulate your emotions. Therefore, it makes sense that this Big Five quality is closely correlated with educational success. In fact C (conscientiousness) may be as important as IQ in predicting our GPA! Because, as teens, they are less apt to succumb to risky behaviors, conscientious boys and girls arrive at the brink of adulthood blessed with superior academic credentials and good health. During adulthood, their conscientious, “workerlike” personalities smooth the path to further success.

360

Conscientious adults have more stable marriages. They tend to be affluent or middle class. Study after study suggests they live longer than their peers because they take such good care of their health (see, for instance, Hampson and others, 2013; Sutin and others, 2013).

For example, let’s take Sara, who ranked high on conscientiousness at age 10. Her hard-

Now, imagine Joe, an emerging-

These descriptions suggest that because our nature (or basic temperamental traits) shape specific life experiences, we should become more like ourselves as we age. Due to an evocative and active process, Sara’s conscientious personality paved the way for her to outshine her contemporaries dramatically at each adult stage. Joe and Calista (mentioned earlier in this chapter), are set up to fail socially and work-

Therefore, what’s astonishing is that twin studies show personality gets less heritable as we age and encounter the random ups and downs of life (Bleidorn, Kandler, & Caspi, 2014; Briley & Tucker-

Making the Maturity Case

One early influence fostering maturity is confronting the challenges of adult life (see Hutteman and others, 2014). As I suggested in Chapters 9 and 10, after leaving the cocoon of our families, we need to emotionally grow up. In a mammoth study exploring the Big Five in 62 nations, researchers found that in every society, agreeableness and extraversion increased from youth into middle age (Bleidorn and others, 2013). Not unexpectedly, however, worldwide conscientiousness rose the most (Walton and others, 2013).

This study also offered compelling evidence that assuming adult roles makes us more mature. In cultures with an earlier onset of marriage or parenthood, people became more conscientious and agreeable at younger ages (Bleidorn and others, 2013).

A delightful example of the power of adult relationships to mold our character (meaning the Big Five trait of conscientiousness) comes from a German study exploring personality changes in relation to the living arrangements of emerging adults. While young people who cohabited with roommates did not increase much in conscientiousness over a four-

361

But emotional growth doesn’t just stop after we assume adult roles. Many people feel more in control of their lives and grow self-

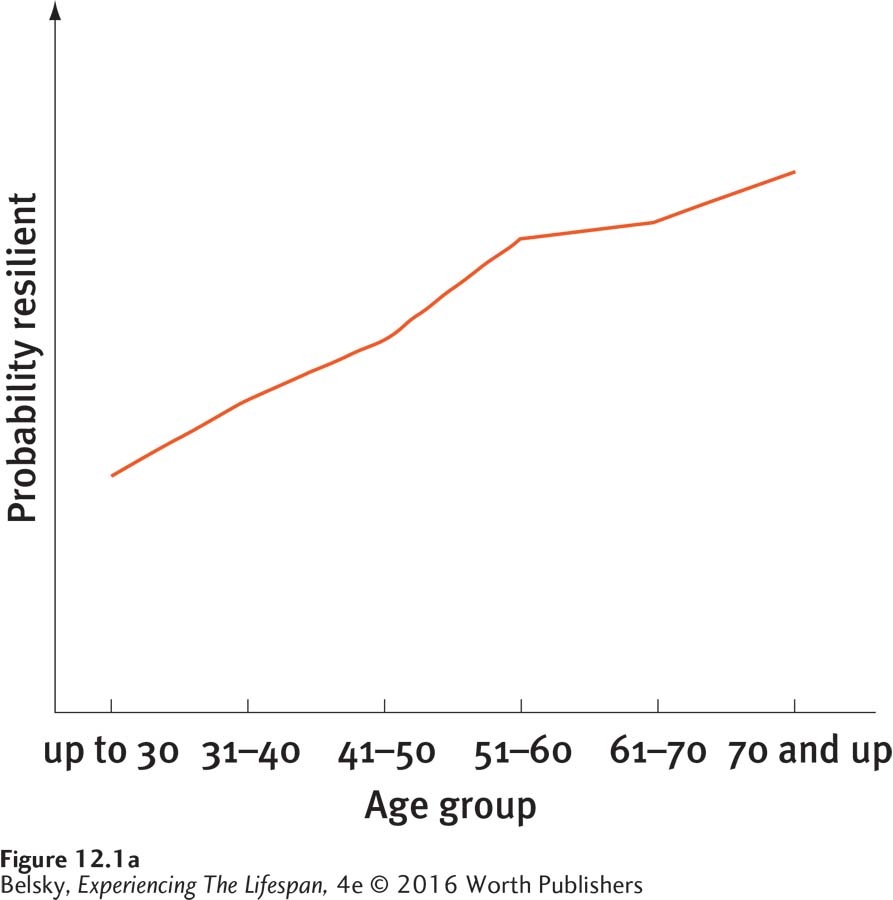

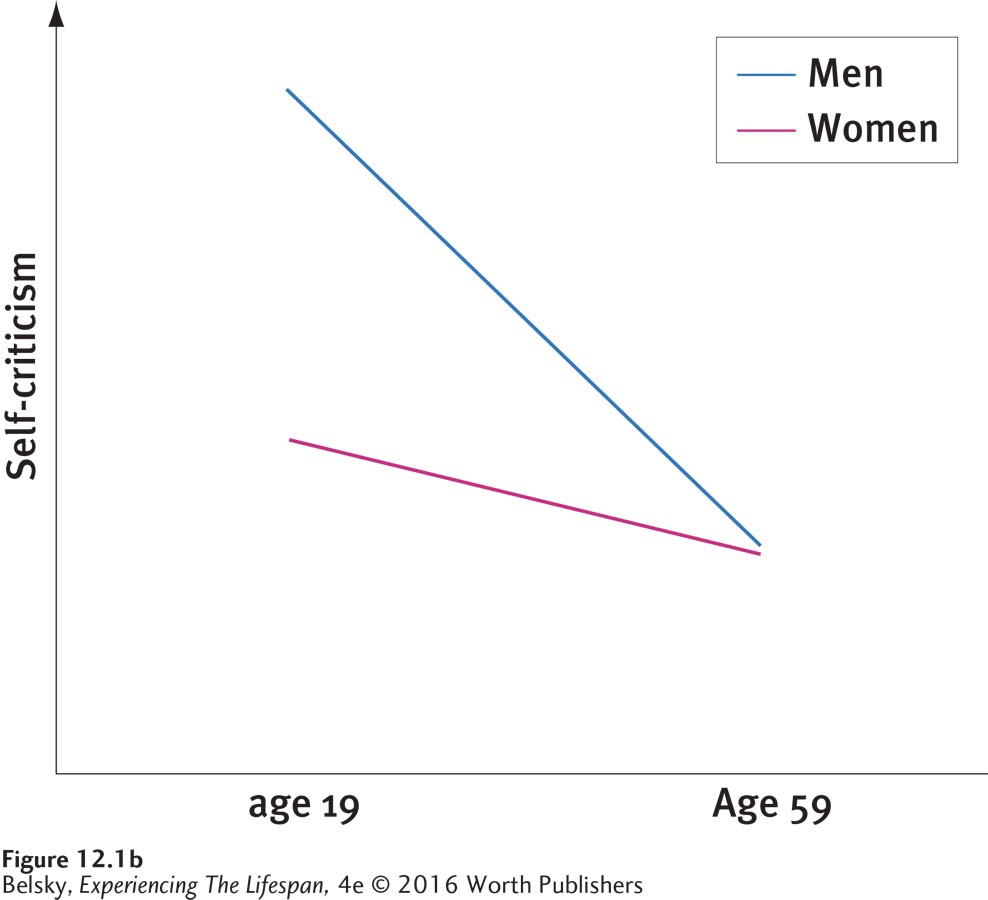

Consider a cross-

Moreover, this self-

362

Obviously, these findings are averages. There are clearly many, selfish “out-

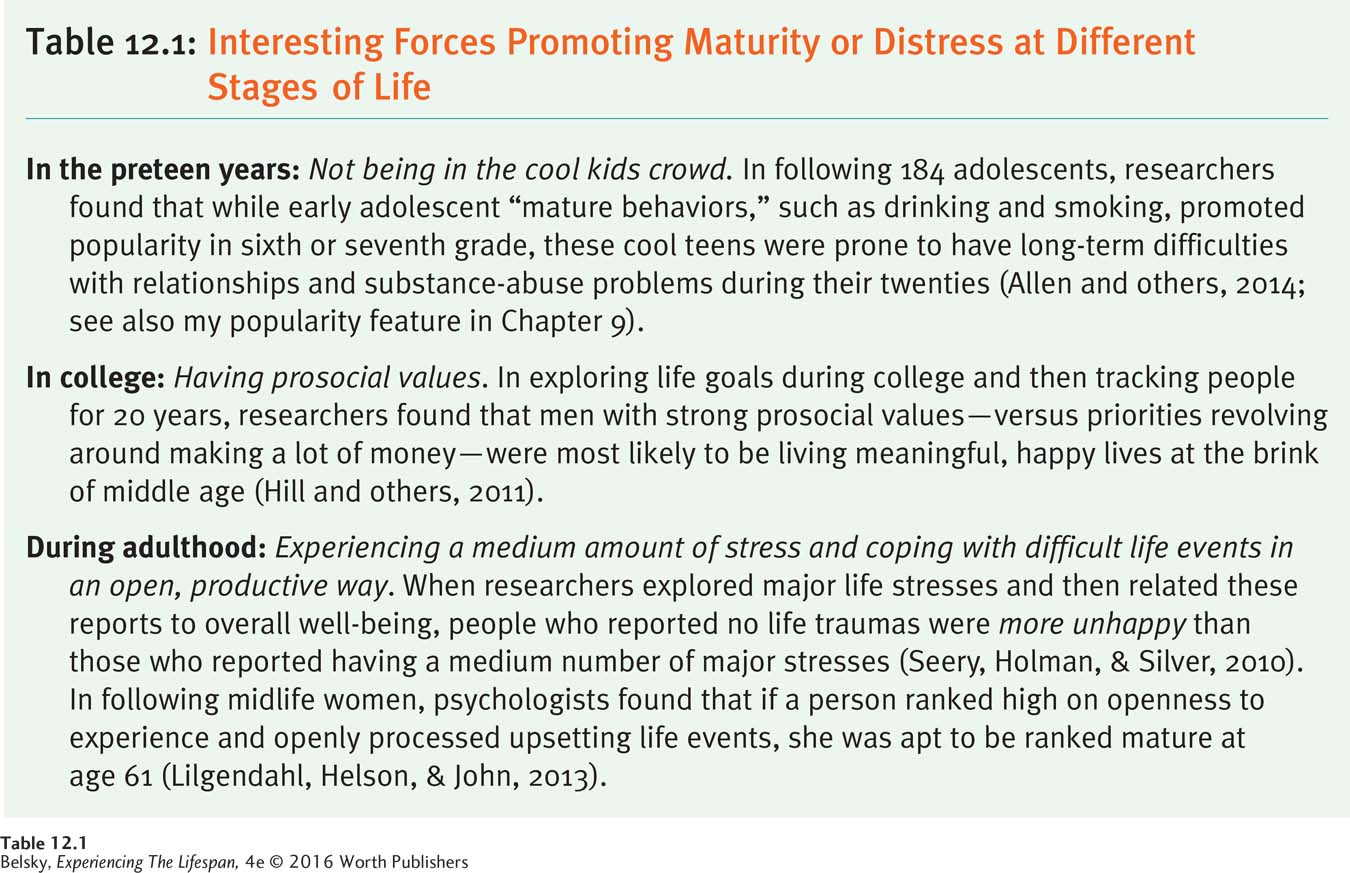

Table 12.1 showcases interesting predictors at different life stages (apart from our rankings on the Big Five) that predict either growing emotionally or having problems down the road. The last item—

Generativity: The Key to a Happy Life

By now you should be impressed with the power of the Big Five to predict life success. But while knowing where we stand on these core dimensions can help reveal our journey’s outcome, it tells us nothing about specifics of the journey itself. Think of several friends who rank high on conscientiousness. One person might be a full-

I was living in a rural North Dakota town and was the mother of a 4-

(quoted in McAdams, de St. Aubin, & Logan, 1993, p. 228)

In listening to these life stories, McAdams realized the power of random life events in shaping personality. Although this woman might have always ranked high in conscientiousness, the specific path her life took was altered by this pivotal experience. In McAdams’s opinion, in order to really understand development, we need to get up close and personal and talk to people about their missions and goals.

363

Examining Generative Priorities

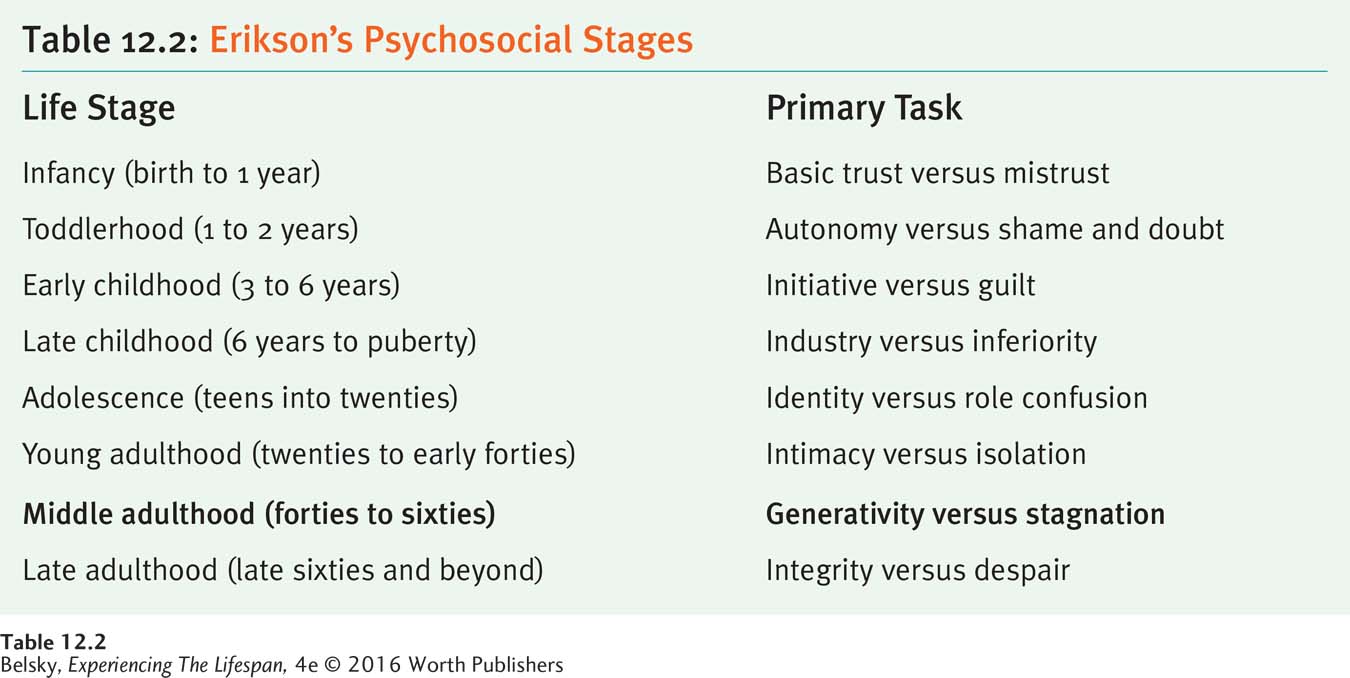

Actually, McAdam’s professional mission has been to scientifically test the ideas of the pioneering theorist who does believe that our goals shift dramatically in different life stages: Erik Erikson. Does generativity, or nurturing the next generation, become our main agenda during midlife? Is Erikson (1969) correct that fulfilling our generativity is the key to feeling happy during “the afternoon” of life? When people in their forties or fifties don’t feel generative, are they stagnant, demoralized, and depressed? (See Table 12.2.)

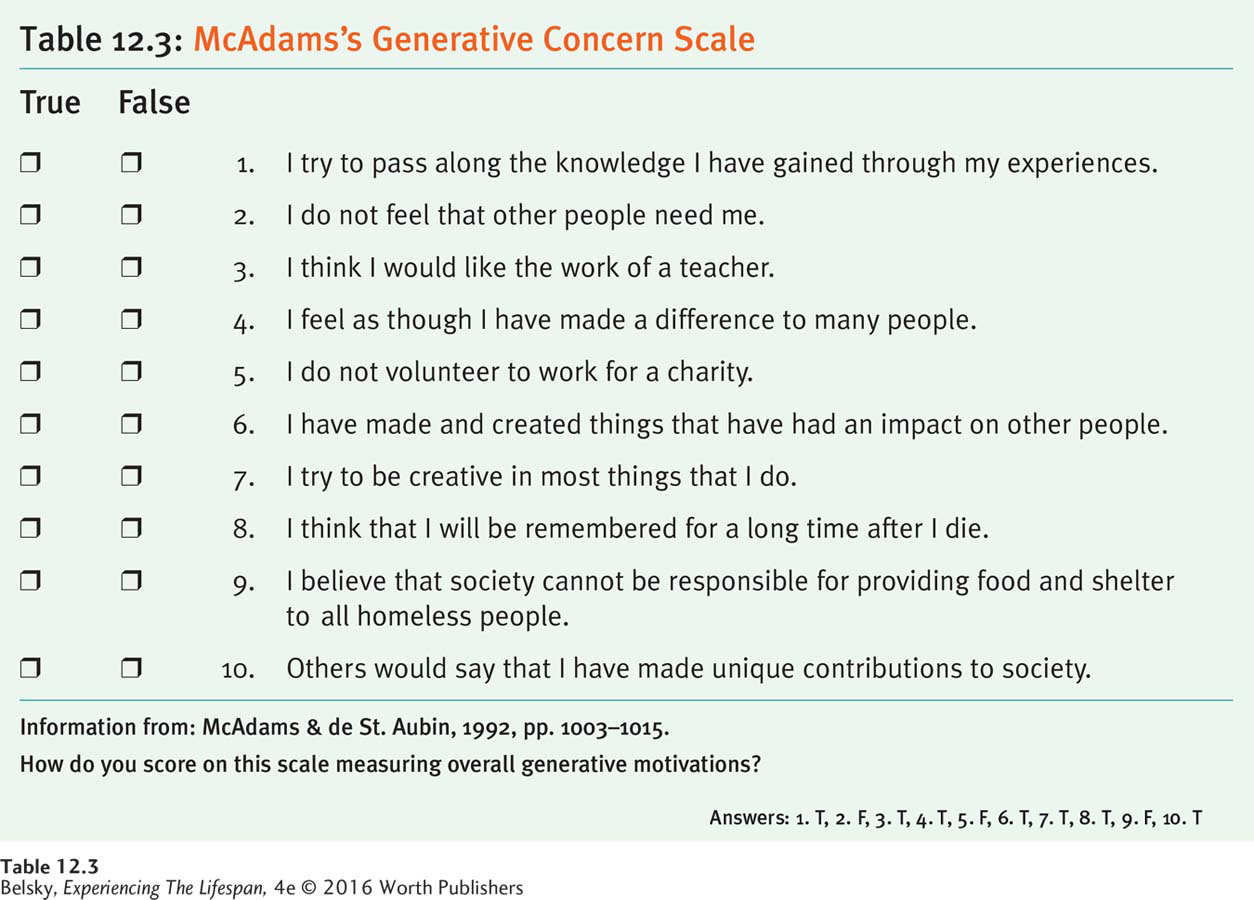

To capture Erikson’s concept, McAdams’s research team constructed a questionnaire to generally measure generative concerns (you can take the first ten items on this scale in Table 12.3). The researchers also explored people’s generative priorities by telling them to “list the top ranking agendas in your life now” (see McAdams, 2001a).

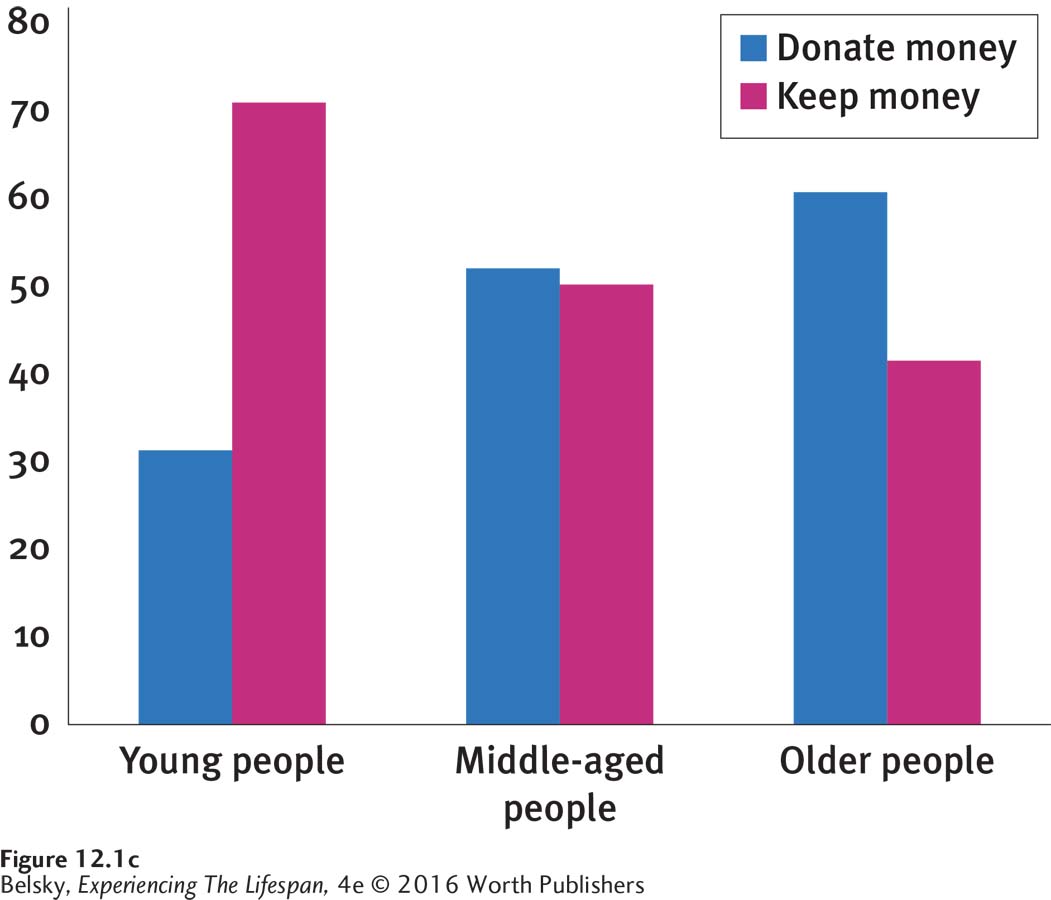

When these researchers gave their measures to young, middle-

364

The researchers did discover age differences in generative priorities—

This makes sense. Remember from Chapters 3 and 6 that prosocial behaviors are in full swing by toddlerhood. There is no reason to think that our basic human drive to be nurturing changes at any life stage. But, just as Erikson would predict, we need to resolve issues related to our personal development before our primary concern shifts to giving to others in the wider world.

Is Erikson right that, as people enter midlife, generativity takes center stage? According to one study, “not necessarily.” In following women from their forties into their sixties, researchers found that issues relating to identity (“developing as a person,” “expanding myself”) remained strong well into middle age. But, as these women got older, generativity gradually grew. According to this research, priorities fully focused on giving to the next generation reach a crescendo in the early sixties, once we know exactly who we are (Newton & Stewart, 2010).

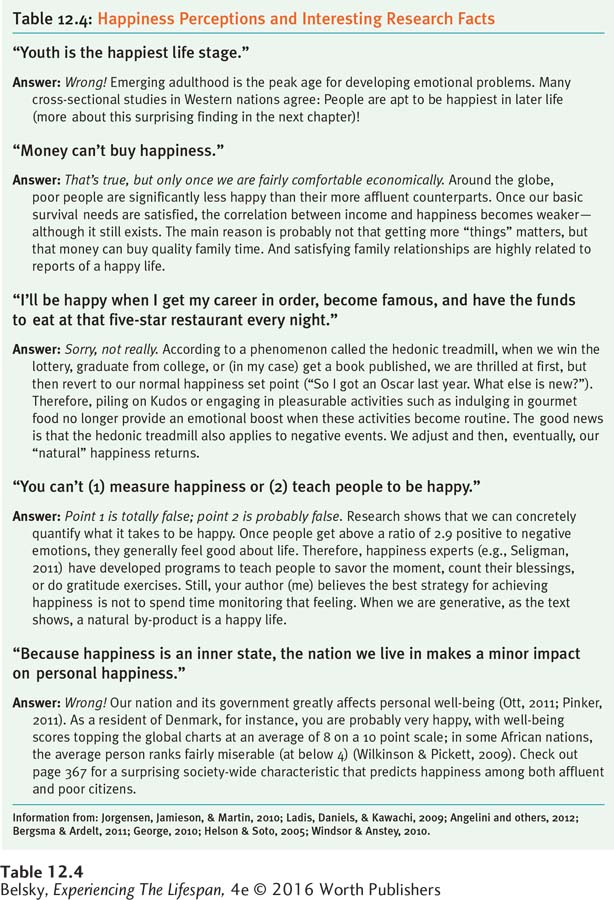

Examining Adult Happiness

Is Erikson correct that generativity is the key to happiness during adult life? Here, the answer is “yes,” as long as we define happiness in the right way. If we imagine happiness as simply “feeling good” (hedonic happiness ), generativity has nothing to do with living a happy life. But, if we consider this term in its richer sense, as having purpose and meaning (eudaimonic happiness ), then, yes, highly generative people do have exceptionally happy lives (Grossbaum & Bates, 2002; Zucker, Ostrove, & Stewart, 2002; Versey, Stewart & Duncan, 2013).

So, generativity makes sense of why sacrificing for a beloved mate makes spouses feel personally fulfilled, or why parents happily spend decades changing diapers when they could be luxuriating in hotel spas (recall the last chapter). Our main mission as adults (and starting from childhood) is not simply hedonic pleasure—

When people don’t have generative goals, do their lives lack meaning? As Erikson described, do these adults feel stagnant—

In reference to the birth of her first child, Deborah wrote, “All actions automatic. No emotional involvement . . . ; totally self-

(adapted from Peterson, 1998, p. 12)

365

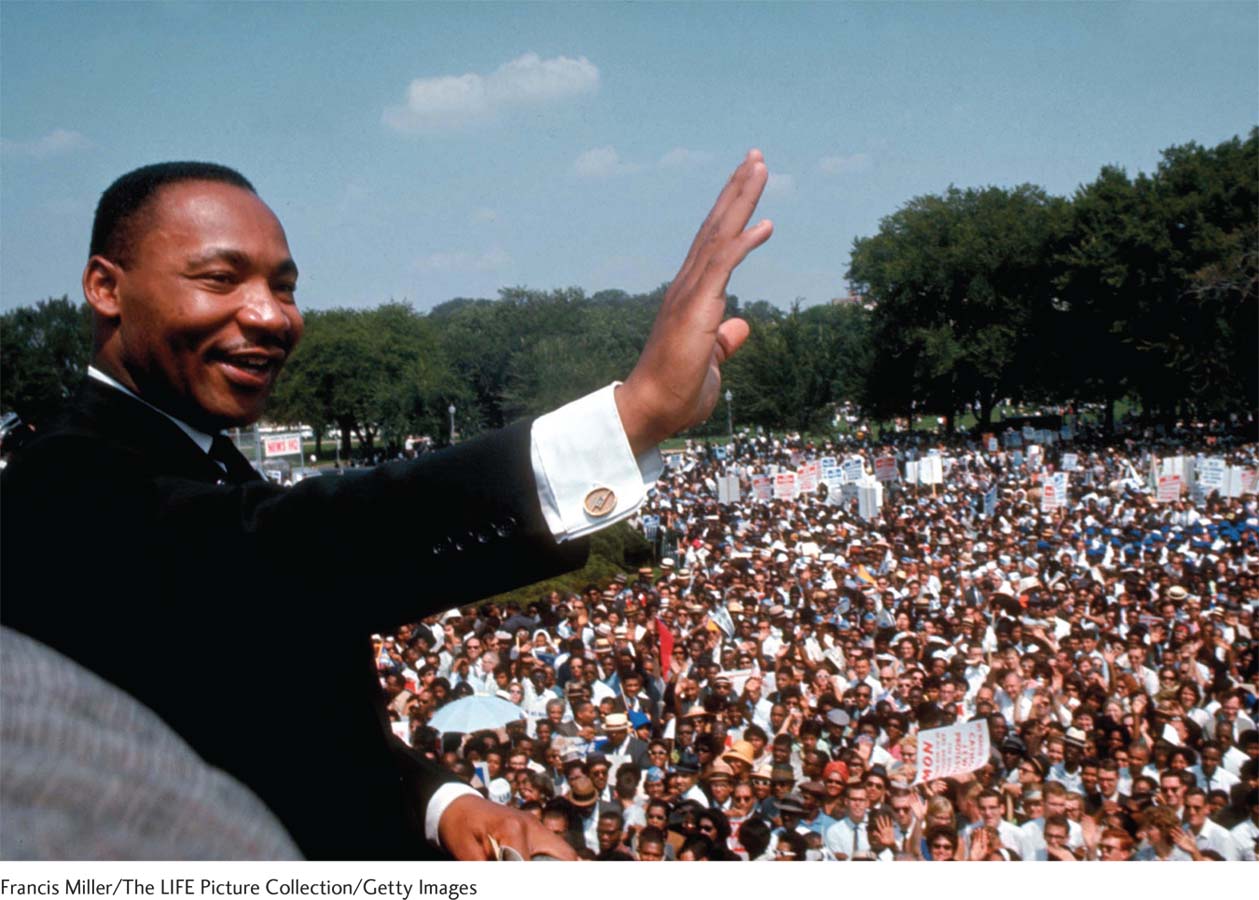

As this case history suggests, having children does not automatically evoke generativity. You can give birth and be totally nongenerative and uninvolved. Conversely, midlife adults who never have children can be incredibly generative in the wider world (see Newton & Baltys, 2014). Classic contemporary outlets for generativity, such as environmental activism, involve caring for generations “not yet born” (Morselli, 2013). Our world-

366

Examining the Childhood Memories of Generative Adults

Do the childhoods of people who embody this rich, Martin Luther King-

The answer was yes. The life stories of highly generative adults had themes demonstrating what the researchers called a commitment script. They often described early memories of feeling “blessed”: “I was my grandmother’s favorite”; “I was a miracle child who should not have survived.” They reported feeling sensitive to the suffering of others, from a young age. They talked about having an identity revolving around generative values that never wavered from their teenage years. A 50-

The most striking characteristic of generative adults’ life stories was redemption sequences —examples of devastating events that turned out in a positive way (McAdams, 2006; McAdams & Bowman, 2001). For instance, in the example I just mentioned, the woman minister might view the humiliation of being sent to prison as the best thing that ever happened, the experience that turned her life around. According to McAdams (2006), early memories of feeling personally blessed, an enduring sensitivity to others’ misfortunes, caring values, and, especially, being able to turn one’s tragedies into growth experiences are the core ingredients of the commitment script and the main correlates of a generative adult life (see also Lilgendahl & McAdams, 2011).

What produces the kind of adult devoted to “repairing the world”? According to McAdams’ interviews, one force may be the presence of caring adults in a person’s past. When his research team asked people in their late fifties to pinpoint emotional turning points in their lives, adults high in generativity described critical incidents involving family members and teachers more frequently than their less generative peers. Here is an example:

The day before my mom died, I went to the hospital . . . and I was actually on my way to pick up my senior pictures. So when I got these photographs I shared them with my mom. . . . I could just tell in her eye that she had this real proud moment . . . it was a moment I . . . treasured . . . she never saw me physically at the graduation, but in my mind I will always believe she was there in spirit. So that will always be a highlight of my life.

(quoted in Jones & McAdams, 2013, p. 168)

If you think of your own generative role models—

In sum, this powerful generativity research explains why raindrops—

Wrapping Up Personality (and Well-

367

Now, let’s summarize all of these messages. Having read this section, here is what you might tell an emerging-

Expect to grow in maturity and especially become much more conscientious, although, in general, your core personality will probably not change much over the years.

Expect to become more self-

assured and altruistic as you travel through middle age. Expect your priorities to shift toward more generative concerns and to grow in generativity, especially during late midlife.

I predict that if you rank high on conscientiousness and the other positive Big Five traits; have prosocial, generative priorities; and deal productively with the traumas in your life, you are on track for a fulfilling middle age—

but don’t hold me to my word, as scientists never know for sure what the future will bring!

As a final note, I must emphasize that it’s difficult to grow emotionally if you are mired in poverty or live in a society rife with conflict and corruption, where life traumas are routine. McAdams’s generative community-

In the next section, devoted to cognition, I’ll be filling in more pieces of the puzzle involved in constructing a fulfilling life.

Tying It All Together

Question 12.1

Tim is going to his thirtieth college reunion, and he can’t wait to find out how his classmates have changed. Statistically speaking, which two changes might Tim find in his undergraduate friends?

They will be more conscientious and self-

confident. They will have different priorities than they did earlier, caring more about nurturing the next generation.

They will care more deeply about making money than they did before.

They will be more depressed and burned out than they were earlier.

a and b

Question 12.2

You are giving your best friend tips about growing emotionally and feeling fulfilled during midlife. Pick the item that should not be on your list:

Live a calm, stress-

free life. Live a generative life.

Develop prosocial goals as a young person.

Be conscientious and open to experience.

a

Question 12.3

Should your professor agree with this suggestion, write about a difficult life experience, and discuss how you coped with that event.

The answers here are up to you, but it would be best to confront and process that event in a way that might promote personal growth.