12.3 Exploring Intelligence (and Wisdom)

368

Remember from Chapter 7 that, when psychologists measure intelligence during childhood, they look mainly at how elementary schoolers perform on standard intelligence tests. Sometimes, they spell out different ideas about what it means to be smart, such as Gardner’s multiple intelligences or Sternberg’s successful intelligence. Developmentalists use standard IQ tests and nontraditional strategies to trace adult intelligence, too.

Taking the Traditional Approach: Looking at Standard IQ Tests

Think of your intellectual role model. Most likely, your mind will immediately gravitate to someone who is 50 or 80—

Mid-

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) , the standard test measuring adult IQ, has a similar format as the WISC, the scale for children, described in Chapter 7. It has verbal items testing different types of knowledge, such as vocabulary and adults’ ability to solve math problems. It also asks test takers to perform relatively unfamiliar nonverbal activities quickly, such as putting together puzzles or arranging blocks. On this part of the test, called the performance scale, speed is essential. People must complete these tasks within a limited time.

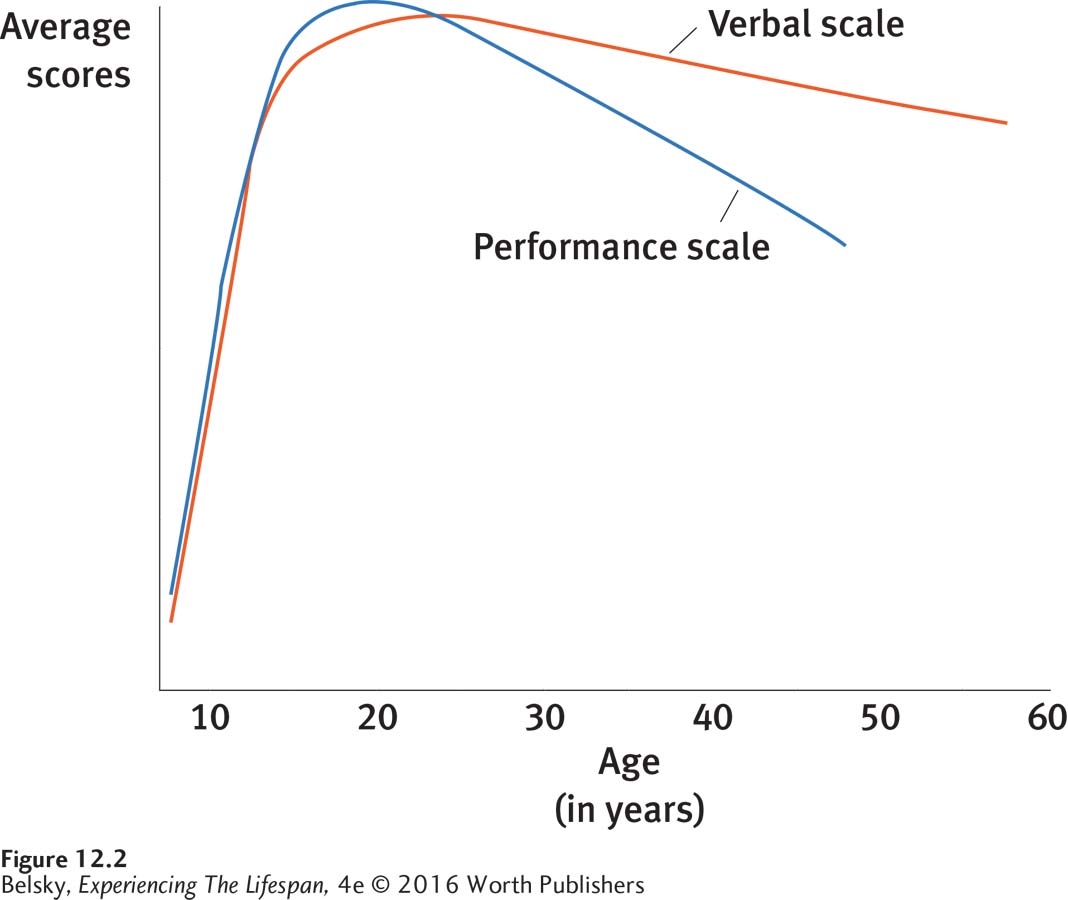

When psychologists tested adults to derive their standards for how people should normally perform on the WAIS at different ages, they discovered that, starting in the twenties, in each older age group, average scores declined. They also found the interesting pattern in Figure 12.2 below. While scores on the verbal sections stayed stable or declined to a lesser degree, average scores on the performance scale steadily slid down, starting in people’s twenties (Botwinick, 1967).

These findings would not give any fifty-

How does our performance on standard intelligence tests really change as we travel through adult life? To answer this question, in the early 1960s, researchers began the Seattle Longitudinal Study —the definitive study of intelligence and age (Schaie, Willis, & Caskie, 2004; Schaie & Zanjani, 2006).

Imagine being a twentieth-

369

Faced with these contrasting biases (longitudinal research will be too positive; cross-

First, the research team selected people enrolled in a Seattle health organization who were 7 years apart in age, tested them, and compared their scores. Then, they followed each group longitudinally, testing them at 7-

Using an IQ test that, unlike the WAIS, measured five basic cognitive abilities, the researchers got a more encouraging portrait of how we change intellectually—

Two Types of Intelligence: Crystallized and Fluid Skills

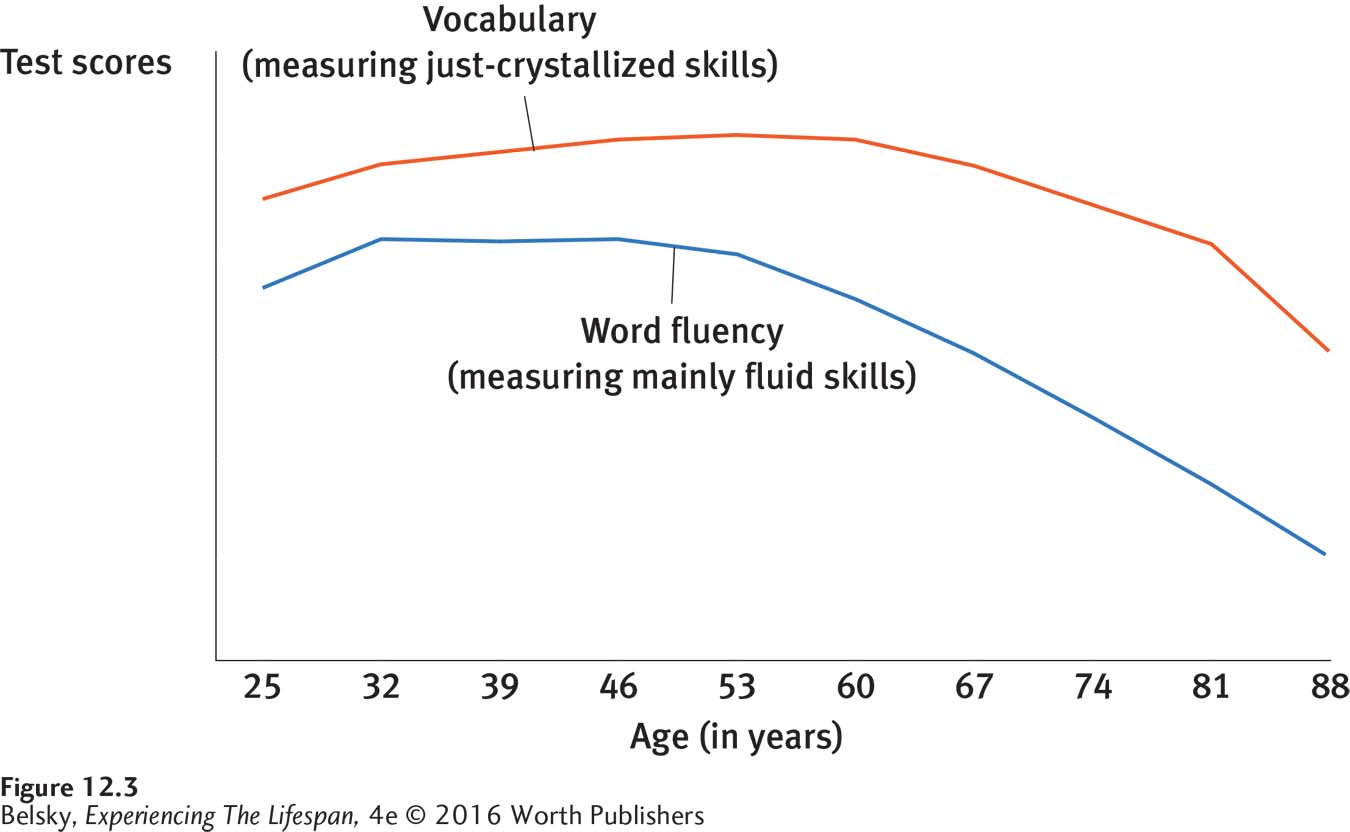

Psychologists today typically divide intelligence into two categories. Crystallized intelligence refers to our knowledge base, the storehouse of information that we have accumulated over the years. The verbal scale of the WAIS, with its tests of vocabulary and math, mainly measures crystallized skills. Fluid intelligence involves our ability to reason quickly when facing new intellectual challenges. The WAIS performance scale, with its emphasis on putting together blocks or puzzles within a time limit, tends to measure fluid skills.

370

Fluid intelligence—

The good news is that, with regard to the most vital crystallized skill—

So, in any situation requiring multitasking, people may notice their abilities declining at a relatively young age. In your late thirties it seems harder to dribble a basketball while keeping your attention on the opposing team. You are having more trouble juggling cooking and having conversations with guests at your dinner parties than at age 25. In old age, these steady fluid losses, as you will see in Chapter 14, progress to the point where they truly interfere with daily life.

The distinction between fluid and crystallized intelligence accounts for why people in fast-

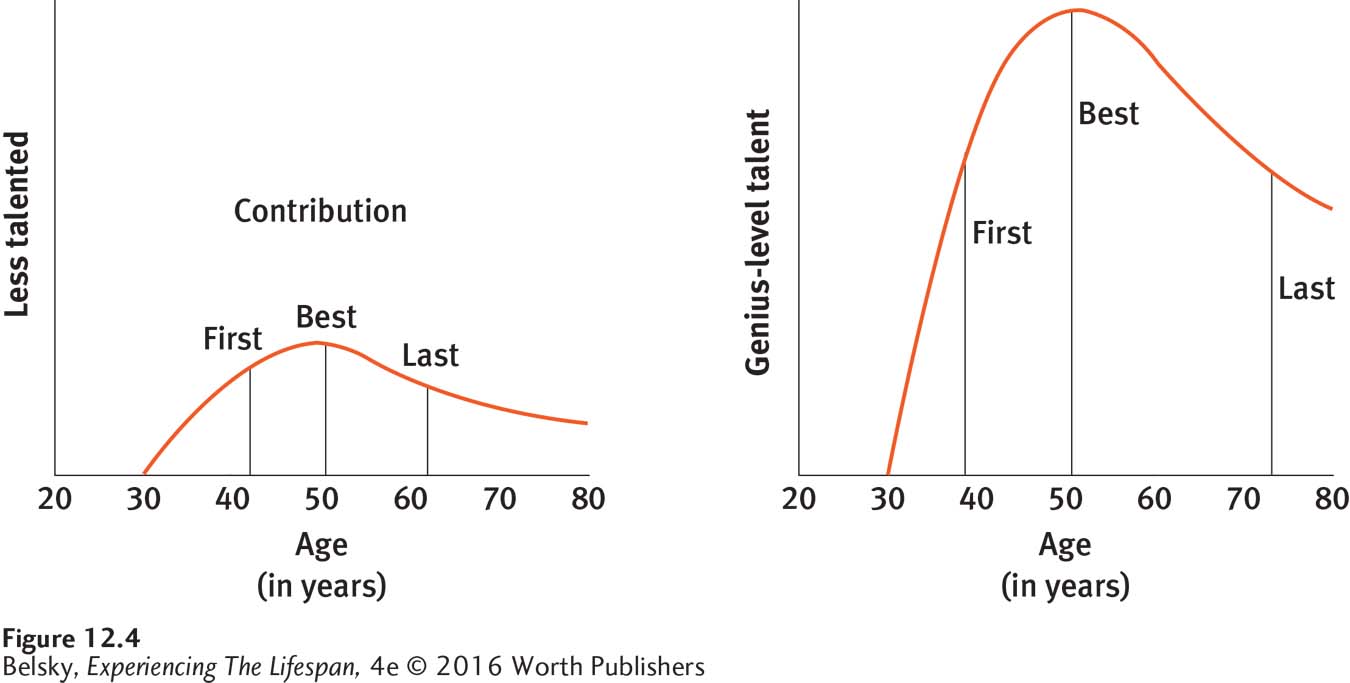

Suppose you are an artist or a writer. When can you expect to do your finest work? Researchers find that when a creative activity is dependent on being totally original, such as dancing or writing poetry, people tend to perform best in their thirties (see Simonton, 2007). If the form of creativity depends just on crystallized experience, such as writing nonfiction or, in my case, producing college textbooks (yes!), people perform at their best in their early sixties (Simonton, 1997, 2002). But in tracing the lives of people famous for their creative work, one researcher discovered that who we are as people, or our enduring abilities, outweighs the changes that occur with age. As Figure 12.4 shows, true geniuses outshine everyone else at any age (Simonton, 1997).

371

So, creatively or career-

The poet Anthony Hecht, at age 70, commented:

I’m not as rigid as I was. And I can feel this in the poems . . . . They are freer metrically, . . . The earliest poems that I wrote were almost rigid in their eagerness not to make any errors. I’m less worried than that now.

(p. 215)

And the historian C. Vann Woodward, at the time in his mid-

Well, [today] I have . . . changed my . . . conclusions. . . . For example, that book on Jim Crow. I have done four editions of it . . . , and each time it changes . . . largely from criticisms that I have received. I think the worst mistake you could make as a historian is to be . . . contemptuous of what is new. You learn that there is nothing permanent in history. It’s always changing.

(p. 216)

From Sigmund Freud, who put forth masterpieces into his eighties, to Frank Lloyd Wright, who designed world-

Staying IQ Smart

Returning to normally creative people, such as you and me, what qualities help any person stay cognitively sharp? What causes our intellectual capacities to decline at a younger-

HEALTH MATTERS. As our mind and our body are “all connected,” the first key to staying intelligent as we age lies in staying physically fit. Hundreds of studies show that physical interventions, as varied as Taekwondo (van Dijk, Huijts, & Lodder, 2013) to resistance exercise (Chang and others, 2014), help keep intelligence fine-

372

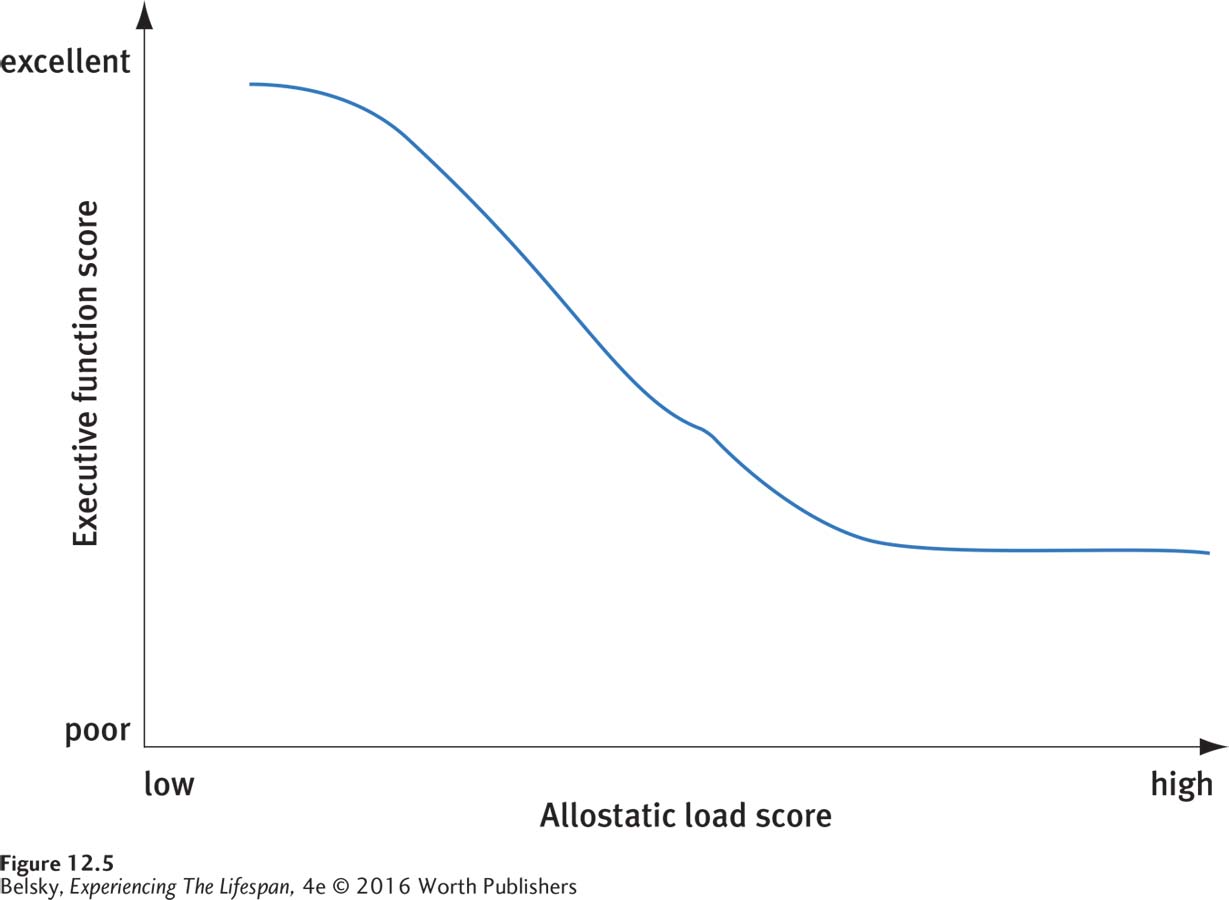

The most powerful scientific evidence that our physical state affects our thinking comes from a mammoth U.S. study tracking thousands of adults. After testing physiological functions spanning heart rate to glucose metabolism, body mass index to cortisol levels, and more, scientists devised an overall physical deterioration score they labeled allostatic load (Karlamangla and others, 2014). As you can see in Figure 12.5, this global index of body dysregulation was strongly related to performance on executive function tests. To put these findings concretely: As an adult with an allostatic load score of 2.7 (the seventy-

Even more compelling (at least for me) is an eerie phenomenon gerontologists call terminal drop. In the first longitudinal studies of cognition, researchers were astonished to discover that they could predict which older people were more likely to die within the next few years by “larger than expected” losses in their verbal IQ (Cooney, Schaie, & Willis, 1988; Riegel & Riegel, 1972). If a person’s scores on tests of vocabulary and other crystallized measures steeply declined, these changes were an ominous early warning sign of a soon-

These studies haunted me the summer when I noticed that my father had suddenly aged mentally. My dad, who was always an intellectual whiz, had lost interest in the world. He was disoriented and depressed. A few months later, my worst fears were confirmed: My father was diagnosed with liver cancer, the illness that was to quickly end his life.

MENTAL STIMULATION (WITH PEOPLE) MAY MATTER. Because, recall from Chapter 3, environmental stimulation promotes synaptogenesis, the second key to staying intelligent should be a no-

To begin our discussion, let’s return to the Big Five—

Professional choices make a difference. People who work in complex, challenging jobs tend to become more mentally flexible with age (Schooler, 1999, 2001; Schooler, Mulatu, & Oates, 2004). Careers involving people—

373

But wait a second! Aren’t adults with challenging jobs apt to be intelligent and well educated to begin with, and also younger health-

The good news, however, is that while we can’t carry out this study with our species, it’s fine to experiment on rats. And, when researchers put a group of rats in a large cage with challenging wheels and swings and then compared their cortexes with control animals, this quiz show treatment produced thicker, heavier brains (Diamond, 1988, 1993). Let’s tentatively accept the widespread idea, then, that, just as physical exercise strengthens our muscles, mental exercise may produce a resilient mind. (I’d be careful about spending hours doing Suduko or other solitary brain-

In sum, people in their forties and fifties are at the peak of their mental powers. But they will have more trouble mastering new cognitive challenges (those involving fluid skills) when under time pressure. To preserve their cognitive capacities as they age, people need to take care of their health and search out stimulating interpersonal and work experiences. And you can tell any worried 50-

INTERVENTIONS: Keeping a Fine-Tuned Mind

Now, let’s look at the lessons the research offers for any person who wants to stay mentally sharp as the years pass.

Develop a hobby that involves physical exercise of some kind—

from dancing to Taekwondo. Stay (or become) passionate to learn new things, and search out careers that expand your mind.

As challenging, interpersonal activities matter most, search for careers that involve complex, people-

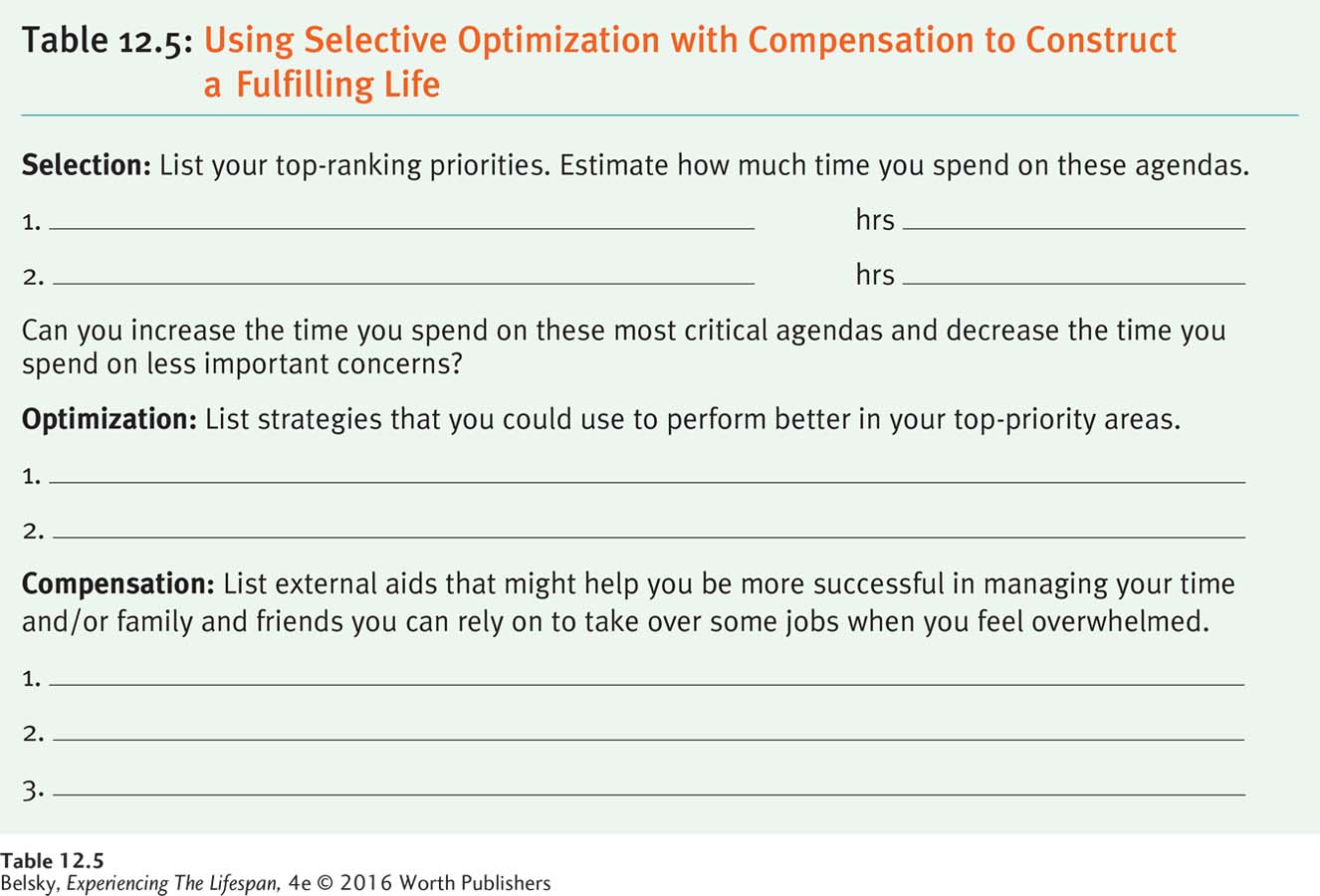

oriented work, or try volunteer activities, like tutoring or serving on a community board. Understand that as you get older, new tasks involving complicated information processing will be difficult. To cope with these losses, you might adopt the following three-

part strategy advocated by Paul Baltes called selective optimization with compensation.

As we move into the older years and notice we cannot function as well as we used to, Baltes believes that we need to (1) selectively focus on our most important activities, shedding less important priorities; (2) optimize, or work harder, to perform at our best in these most important areas of life; and (3) compensate, or rely on external aids, when we cannot cope on our own (Baltes, 2003; Baltes & Carstensen, 2003; Krampe & Baltes, 2003).

Let’s take Mrs. Fernandez, whose passion is gourmet cooking. In her fifties, she might decide to give up some less important interest such as gardening, conserving her strength for the hours she spends at the stove (selection). She would need to work harder to prepare difficult dishes demanding split-

374

Although Baltes originally spelled out these guidelines to apply to successful aging, they are relevant to anyone coping with the demands of daily life—

Taking a Nontraditional Approach: Examining Postformal Thought

So far, I have been mainly discussing the insights related to intelligence derived from traditional IQ tests. But look back at the quotations from the older poet Anthony Hecht and the historian C. Vann Woodward, on page 371. The qualities these creative people were describing have nothing to do with putting together puzzles or blocks. What stands out about these men is their openness to experience and sensitivity to their inner lives. Given that standard IQ tests were devised to predict performance in school, perhaps it would make sense to come up with a test to capture the qualities that define thinking intelligently during adult life.

Jean Piaget described qualitative changes in cognition that occur in children as they age. So developmentalists drew inspiration from this landmark theory to construct an adult-

Recall Piaget believed that we develop cognitively through hands-

POSTFORMAL THOUGHT IS RELATIVISTIC. As you saw in Chapter 9, adolescents in formal operations can argue rationally about rights and wrongs. With age and life experience, we realize that most real-

375

POSTFORMAL THOUGHT IS FEELING-

POSTFORMAL THOUGHT IS QUESTION-

Clearly, we cannot measure this kind of intelligence by giving tests in which questions have a single correct answer. We need to adopt the strategy that Lawrence Kohlberg used with his moral dilemmas (recall Chapter 9): Present people with real-

John is known to be a heavy drinker, especially when he goes to parties. Mary, John’s wife, warns him that if he gets drunk one more time, she will leave him and take the children. John goes to an office party and comes home drunk. Does Mary leave him? How sure are you of your answer?

If you answered this question rigidly (“Mary said she would leave, so she should; yes, I am sure I am right”), you are not thinking postformally. You must explore the consequences of leaving for Mary, for John, and for the children. You must understand that any answer you gave would be a judgment call.

Actually, astute readers may be thinking that the qualities involved in postformal thinking have uncanny parallels to the same personality attributes involved in growing emotionally with age: Be open to experience; confront and process negative life events in a thoughtful way.

Since post-

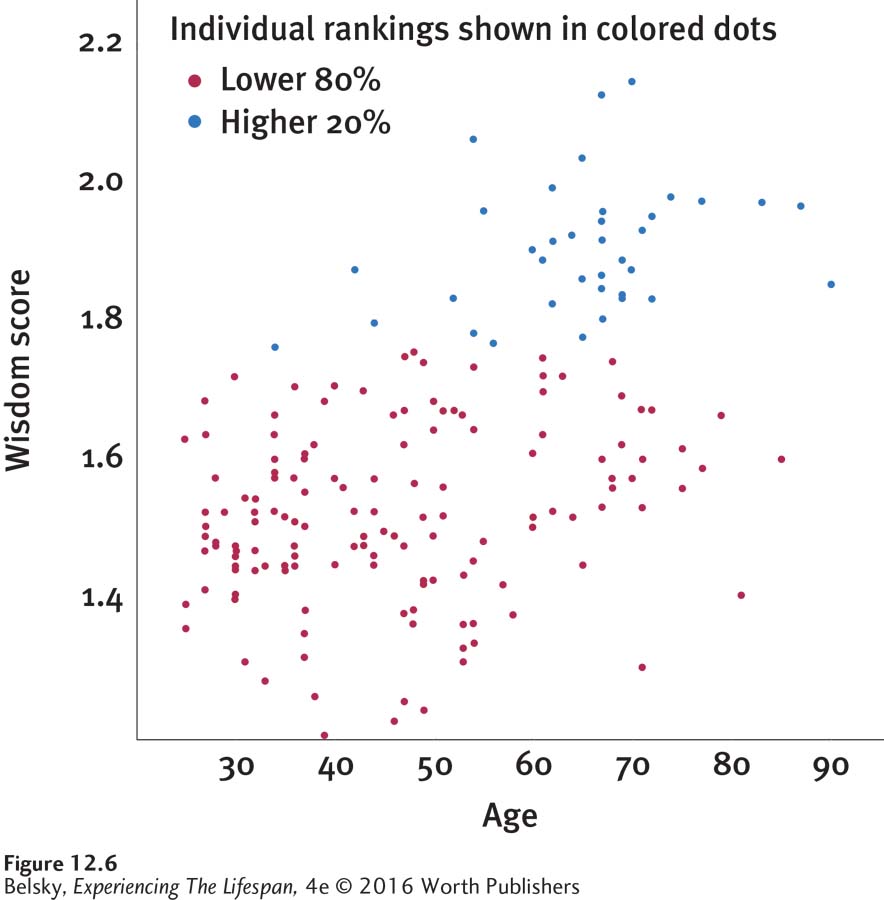

Psychologists (Grossmann and others, 2010) asked adults to talk about social/ethnic conflicts: “The Issi want to preserve that nation’s traditions, and the Assari want social change. What will happen? What would you advise?” They wondered: Would older people discuss the problem from each group’s vantage point and realize that the outcome was uncertain? Would they understand change comes gradually and stress the need for compromise?

As you can see by the blue dots in Figure 12.6, the answer was yes. Notice that a few middle-

376

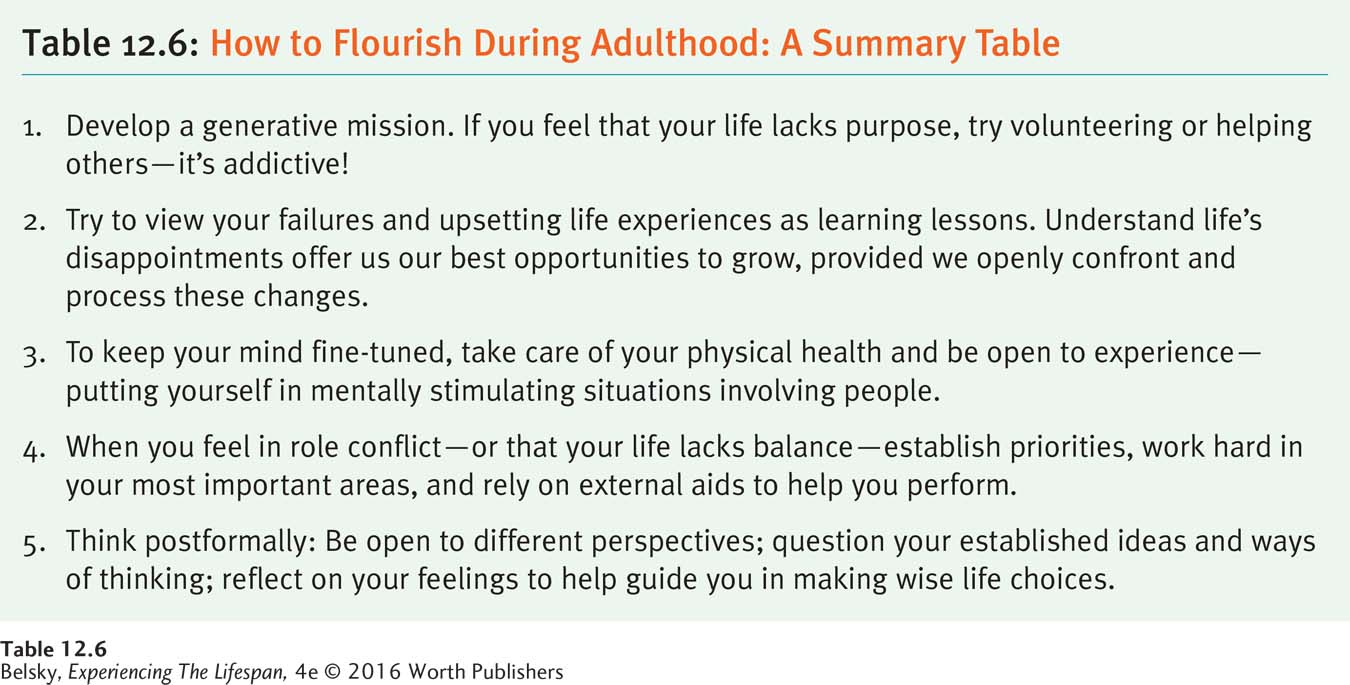

Now, returning to what we have learned so far, what lessons does this whole chapter have for constructing a fulfilling life? Table 12.6 summarizes all of these insights in a chart that offers tips for flourishing during adult life.

Until this point, I have been discussing issues that are relevant to people in their twenties, their forties and fifties, and even adults aged 95. In the next section, I’ll explore transitions unique to the middle years.

Tying It All Together

Question 12.4

Andres is an air traffic controller and Mick is a historian. Pick which man is likely to reach his career peak earlier, and explain the reasons why.

Andres will reach his career peak far earlier than Mick because his job is heavily dependent on fluid skills. A historian’s job depends almost exclusively on crystallized skills.

Question 12.5

Your author (me) is writing another textbook on lifespan development. I am also learning a new video game. Identify each type of intellectual skill involved and describe how my abilities in each of these areas are likely to change now that I am in my sixties.

Textbook writing is a crystallized skill, so I should be just as good at my life passion during my sixties—

Question 12.6

Rick says, “I’ve got too much on my plate. I can’t do anything well.” Identify the theory discussed in this chapter that would be most helpful in addressing this problem, and explain what this theory would advise.

The theory that applies to Rick’s problem—

Question 12.7

Kayla is contemplating breaking up with her boyfriend, Mark, because, she says, “He doesn’t give me the attention I need.” Name the advice a postformal thinker would not give to Kayla.

“Leave the bum!”

“Think of what is going on from Mark’s perspective—

for instance, is he overworked?” “Whatever choice you make, look at all the angles.”

“There may be no ‘right decision.’ Go with your gut.”

a