12.4 Midlife Roles and Issues

As I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, classic midlife events can be sources of joy and issues for concern. On the uplifting side, there is that terrific life experience called grandparenthood. The downside may be the need to care for disabled aged parents, and to face sexual decline. Let’s now look at these “aging phase of life” joys and concerns one by one.

377

Grandparenthood

The (Lakota) grandparents always took . . . the first grandchild to raise. They think that . . . they’re more mature . . . and they could teach the children a lot more than the young parents. . . . I’m still trying to carry on that tradition because my grandmother raised me most of the time up until I was nine years old.

(quoted in Weibel-

This comment from Mrs. Big Buffalo, a Native American grandmother, reminds us that every adult role, from spouse, to parent, to worker, to grandparent, is shaped by our society. Native American and Hawaiian grandparents are apt to see raising grandchildren as “our custom” (Yancura, 2013). In Western cultures, where we put a priority on the nuclear family, grandparents are more peripheral to family life. In most societies, maternal grandparents (the daughter’s parents) are more involved with the grandchildren. In China, it’s the moms and dads of sons (Xu, Silverstein, & Chi, 2014).

Still, even in Western nations, where tradition dictates taking a hands-

Exploring the Grandparent Mission to Care

Because human beings are the only species with female bodies programmed to outlast the reproductive years, evolutionary theorists argue, the answer is yes. Menopause, they believe, evolved to offer an extra layer of mothers, without their own childrearing distractions, to care for the young (Coall & Hertwig, 2010). Put bluntly, grandmas function to help our species survive.

This lifesaving function is apparent in subsistence societies. Remember from reading the Experiencing the Lifespan box in Chapter 3 that, in Ghana, a grandma often steps in to take care of the family so her daughter can make the weekly trek to the clinic to stave off death in a young, malnourished child. Therefore, in Africa, the presence of a grandmother reduces mortality rates during the early years of life (Gibson & Mace, 2005).

In our culture, grandparents do their lifesaving selectively. As family watchdogs, they step in during a crisis to help the younger family members cope (Dunifon, 2013). At these times, their true value shines through. Grandparents are the family’s safety net (Troll, 1983).

In more normal times, grandparents function as mediators, helping parents and children resolve their differences (Kulik, 2007). They serve as cheerleaders and reinforcers of prized family norms (Dunifon, 2013) (“Wow you got on the honor role. Nana is SO proud!”). Grandparents can be the family cement, keeping cousins close. From Christmas get-

Grandparents serve as symbols of connectedness within and between lives; as people who can listen and have the time to do so; as reserves of time, help, and attention; as links to the unknown past; as people who are sufficiently varied, flexible, and complex to defy easy categories and clear-

(Hagestad, 1985, p. 48)

You may notice this complexity and flexibility in your own family. One grandparent might be a shadowy figure; another may qualify as a second mother or best friend. Some grandparents love to jump on trampolines; others show their love in “baking cookies” ways. An intellectual grandpa may take you to lectures; a fishing grandpa may take you on the lake.

378

Which Grandparents Are More or Less Involved?

What forces determine how involved a particular grandparent is likely to be? Gender matters. Study after study agrees that grandparenthood is a more joyous, emotionally central role for women than men (Findler and others, 2013). Perhaps because they have spent so many decades as “old style” distant dads, grandfathers more frequently report having trouble connecting emotionally with their grandchildren than do their wives (Ben Shlomo, 2014).

Physical proximity makes a huge difference—

Age matters—

These quotations—

And a side benefit of friending your grandchild on Facebook is that you can feel closely connected without having any conversation at all: “I keep my mouth shut” said another grandma. “They know I’m there (on Facebook) and they are comfortable with it . . . if I got on the phone with them and tried to have them tell me . . . the things they do, it wouldn’t happen” (2014, p. 93).

Grandparent Problems

Grandparents take pride in the fact that they are free to “be there” to lovingly listen, and to leave the disciplining to mom and dad. But my discussion implies grandparents are really not free. For one thing, it’s important to hold your tongue and not criticize your child’s parenting, because your access to the grandchildren depends on having a good relationship with the generation in between (Sims & Rofail, 2013; Lou and others, 2013).

Now imagine your built-

Being in this situation created heartache for a friend of mine, when this preference for maternal moms cost her physical proximity. Her daughter-

379

The allegiance to one’s family of origin can have devastating effects after a divorce. When the wife gets custody, and especially if she remarries and has other children, she can lock her ex-

When people get locked out of seeing their grandchildren—

Then there is the opposite situation—

Caregiving grandparents take full responsibility for raising their grandchildren. In recent decades, the ranks of these grandparents have swelled. In the 2010 census, 7.5 million U.S. children lived with a grandparent. The number of grandparents having primary care for that grandchild doubled over the past 40 years (Rubin, 2013). Although they span the socioeconomic spectrum, caregiving grandparents tend to be poor. In extreme cases, these front-

How does it feel to take this step? As you might expect, custodial grandparents are typically deeply distressed, mourning the fact that their own son or daughter—

[The police in a different state] said to me, “Ma’am, if you don’t get here in 72 hours, then your grandson will be put in the [state protective services system] and you will have to fight to get him.” I said, “I will fight from the moment I get there if my grandson is not there for me.”

(quoted in Climo, Terry, & Lay, 2002, p. 25)

And another woman summed up the general feeling of the custodial grandmothers in this study when she blurted out: “Nobody is going to take [my grandson] away from me. I have done everything except give birth to him” (quoted in Climo, Terry, & Lay, 2002, p. 25).

These women, mainly in their late fifties, complained about feeling physically drained: “Some days I feel really old, like I just can’t keep up with him” (quoted in Climo, Terry, & Lay, 2002, p. 23). They had mixed emotions about their situation: “Some days I feel real blessed by it, other days I want to sit and cry” (p. 25). They sometimes described redemption sequences, too: “God has given me this wonderful little boy to raise and I’m thinking, ‘How many people get the opportunity to do it a second time?’” (p. 26).

Parent Care

Ask friends and family members and they will tell you that becoming a grandparent is one of the joys of being middle-

380

Caring for parents violates the basic principle in Western cultures that parents give to their children, not the reverse (Belsky, 1999). So, it makes sense that while older people may welcome help from siblings or a spouse, they prefer being the “givers” (or help providers) with an adult child. Moreover, as you might expect from the vow “in sickness and in health,” elderly spouses find caregiving far less burdensome than daughters or sons do (Perrig-

Actually, let me get personal and relate all of this to Chapter 11. When older people are happily married, sacrificing for a chronically ill spouse is not a burden, but a source of fulfillment. It’s definitely a “labor of love.”

Unfortunately, this is often not true with parent care. Because caring for an ill parent is typically a woman’s job, it can produce role conflict, when a daughter or daughter-

At this point, I need to set the record straight: The phenomenon called the “sandwich generation”—women pulled between caring for their young children and disabled elderly parents—

Finally, the belief that in Asian cultures or in U.S. groups with more collectivist values, children are “happy” to care for aging parents is also untrue (Freeman and others, 2010; Hashizume, 2010). In Japan, for instance, with polls showing one in two middle-

The answer—

The older person’s personality looms large. Parent care, as you will see in Chapter 14, poses particular challenges with Alzheimer’s disease. According to one alarming study, if a caregiver perceived a parent as difficult and manipulative and became resentful, the situation could escalate to screaming, yelling, or threatening that person with a nursing home (Smith and others, 2011).

381

Still, caring for a disabled parent can have the opposite effect. It may offer its own redemption sequence, giving children the chance to repay a beloved mother or father for years of care (Kramer & Thompson, 2002). Moreover, as with other life stresses, productively confronting this challenge can help midlife children grow emotionally and become “wiser,” especially about planning for their lives when they become old (Pope, 2013).

Balancing the need to respect a frail older parent’s autonomy and knowing when to intervene (Funk, 2010); being generative with the grandchildren, but not intrusive, while balancing your own and your family’s needs: These are the kinds of complex relationship challenges that explain why, in Jung’s evocative words, the long “afternoon of life” may teach us to be wise.

Body Image, Sex, and Menopause

Jung famously believed, “We cannot live life’s afternoon by the program of life’s morning”—meaning that the key to growing mature with age lies in giving up the quest for physical beauty in favor of more spiritual concerns. But judged by our contemporary passion for cosmetic surgery, how many twenty-

The (somewhat) good news is that while fifty-

Exploring the Facts Relating to Physical Sexual Decline

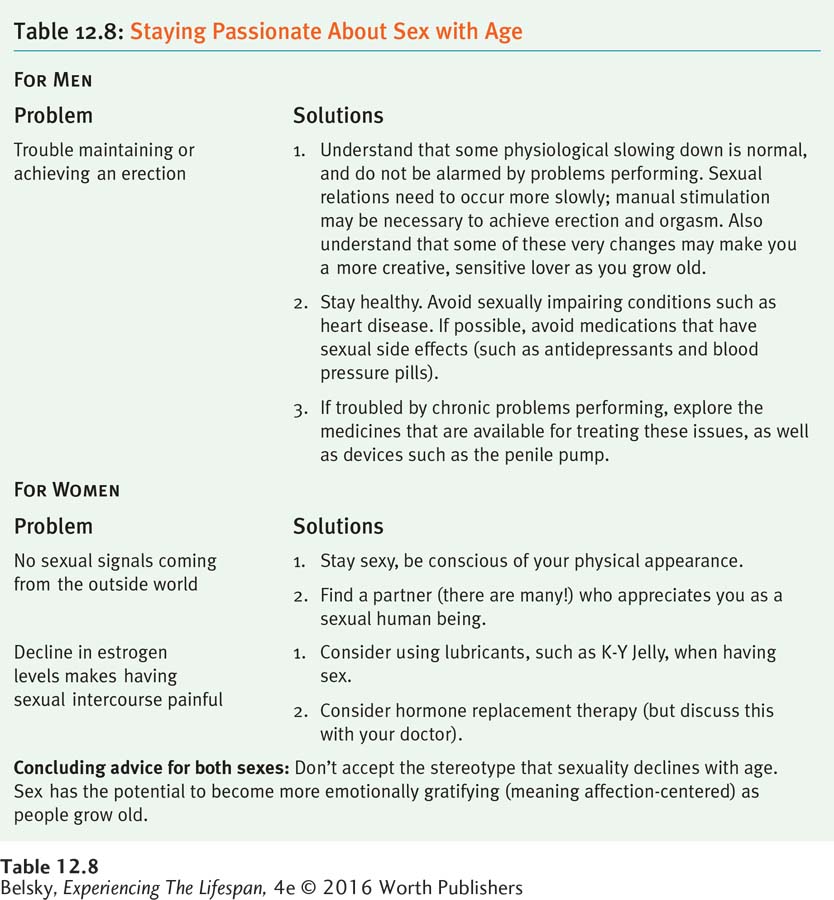

The findings for middle-

Because their sexual apparatus does not critically depend on blood flow, older women can be just as orgasmic at 80 as at age 20. Unfortunately, however, in middle age, women are more apt to turn off to sex than men. The reason is environmental: being without a partner (due to widowhood or divorce); having an older spouse with a chronic disease; not having anyone respond to you as a sexual human being. Menopause can indirectly affect sexuality, too.

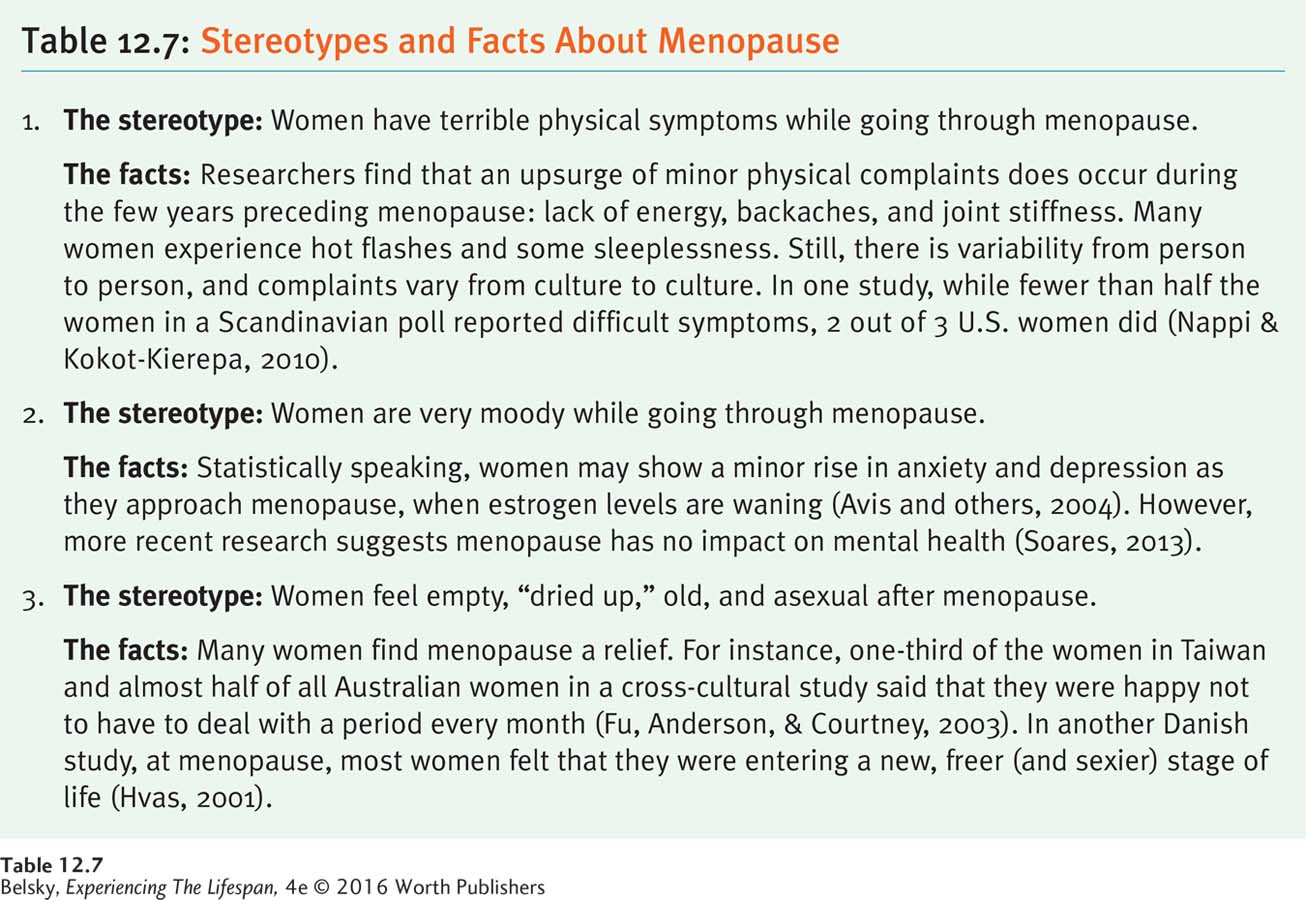

Menopause typically occurs at about age 50, when estrogen production falls off dramatically and women stop ovulating. Specifically, the defining marker of menopause is not having menstruated for a year. As estrogen production declines and a woman approaches this milestone, her menstrual cycle becomes more irregular. During this sexual winding-

382

This estrogen loss produces changes in the reproductive tract. After menopause, the vaginal walls thin out and become more fragile. The vagina shortens, and its opening narrows. The size of the clitoris and labia shrinks and blood flow tends to decrease. It takes longer after arousal for lubrication to begin (Masters & Johnson, 1966; Saxon, Etten, & Perkins, 2010). Women don’t produce as much fluid as before. These changes can make having intercourse so painful that some women stop having sex.

Baring the Real Sexual Truth

By now readers might be sadly thinking, “I’d better enjoy my current sex life, because my sexual self will probably evaporate when I get old.” Not so fast!

Yes, being partnerless, or having a husband who is ill, can stop sexuality in the older years (Syme and others, 2013). However, well into later life, many couples still enjoy sex (Trudel and others, 2014). In one national Swedish study, 2 in 3 men in that nation over age 70 reported still having intercourse. The odds for 70-

And if you assume male performance problems signal the death of decent sex, think again. In one survey, while admitting their erectile problems were troubling, middle-

383

Another 84-

This lovely description makes sense of why, in one survey, during their older years, men and women, lesbian, gay, and bisexual couples, described great sex in similar ways: It’s all about intimacy, communication, and authenticity. Moreover, many respondents reported that their current lovemaking was better than the sex they had when young! (See Kleinplatz and others, 2013.) The only group who disagreed were sex therapists—

Table 12.8 summarizes the male and female changes described in this section, and offers advice for staying passionate about sex as you age.

How do we change physically, cognitively, and personality-

Tying It All Together

384

Question 12.8

Juanita, aged 4, has two grandmothers, Karen and Louisa. Grandma Karen is much more involved with Juanita than is Grandma Louisa. List two possible reasons why this might be. As Juanita gets older you might expect her to get more/less involved with Grandma Karen.

Karen may live closer to Emma. Most likely she is a maternal grandma. As Juanita gets older you would expect her to be less involved with her grandma.

Question 12.9

Poll your class. Do most people report being closest to their maternal grandmother (or grandfather)? Does your class feel that technology is increasing their sense of connection to grandparents (and, if so, perhaps they could give specific examples).

Answers here will vary.

Question 12.10

Kim is caring for her elderly mother, who just had a stroke. Each of the following should make Kim’s job feel easier except:

Kim views caregiving as an opportunity to repay her mom for years of love.

Kim’s mom has a mellow personality.

Kim has several siblings.

c

Question 12.11

For the following “age and sexuality” statements, select the right gender: Males/Females decline the most physiologically Male/female sexuality is most affected by social issues (such as not having a partner).

Males decline the most physiologically; female sexuality is most affected by social issues (such as the lack of a partner).

Question 12.12

Summarize, to a friend, how sexuality changes in middle and later life.

Although the “physical sexual facts” show declining performance is universal, especially for men, many people remain sexually active into later life. Because sex is more centered on affection, many older adults say lovemaking is actually better at their age.