13.1 Setting the Context

Long life expectancies, declining fertility, the baby boomers reaching old age—all of these forces explain why the median age of the population is increasing and why, in the decades to come, more people will look closer in age to this elderly woman than her 22-year-old granddaughter.

Jens Lucking/MECKY/Getty Images

The well-known reason for this invasion is the baby boomers marching into their young-old years. Moreover, due to our twentieth-century advances in life expectancy, when people reach that magical sixty-fifth birthday, they can now expect, on average, to live for 18 more years (Adams & Rau, 2011).

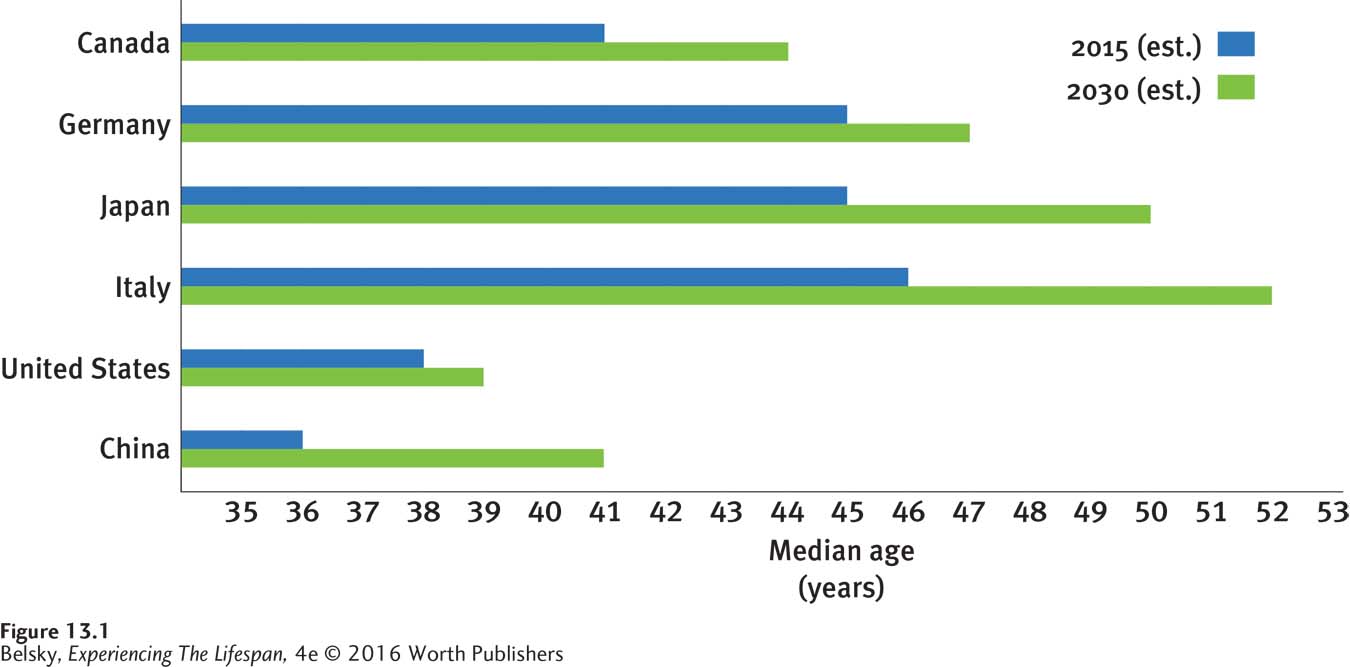

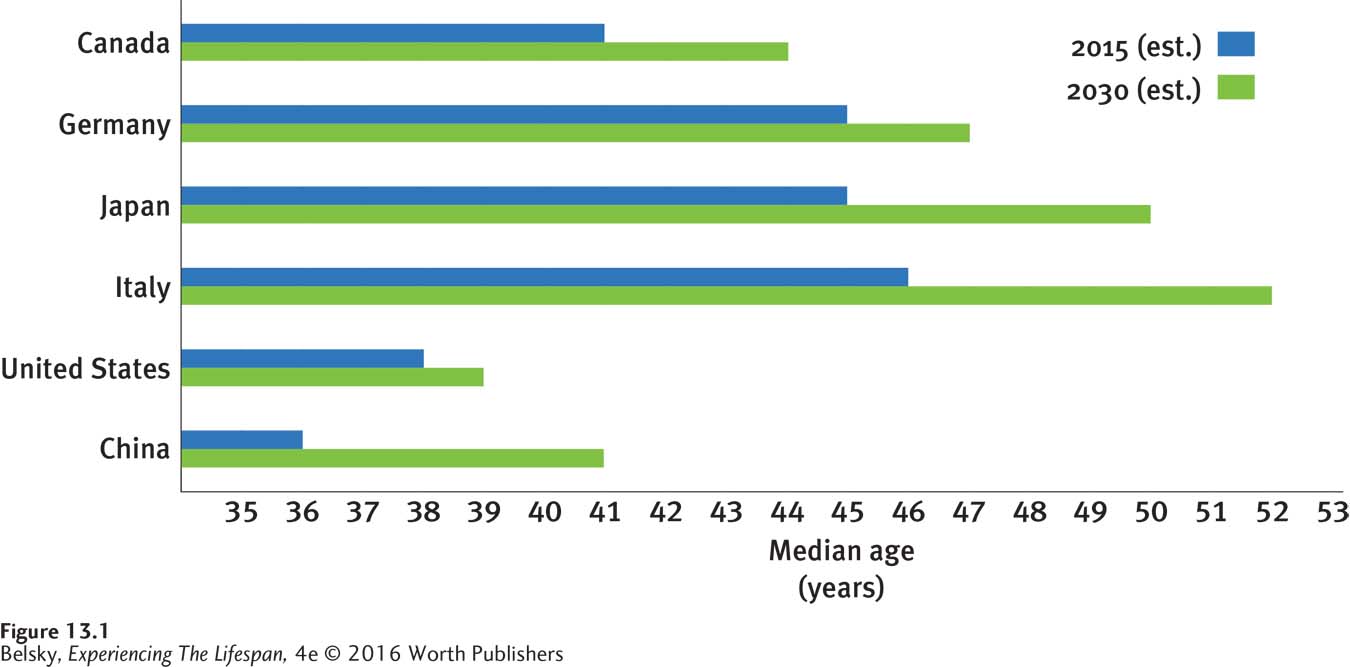

Falling fertility is also producing this unique historic demographic change (Cherlin, 2010; recall Chapter 11). When birth rates decline, the median age of a nation—the cutoff age at which half of the population is older and half is younger—tends to rise. With childbearing rates dipping sharply in Europe and Asia in recent decades, the median age of the population in most developed countries is now well into middle age.

The baby boomers, longevity, and low fertility are converging to produce our new, old world. You can track this demographic storm as it peaks in specific nations in Figure 13.1. In 2030 in Japan, where average life expectancy now tops age 81 and fertility rates are low, the median age of the population will be roughly age 50. In Italy, 1 out of every 2 people will be at least 52. And in that same year, roughly 1 in every 5 Americans and 1 in 4 Europeans will be over age 65 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2008).

Figure 13.1: Predicted median age of the population, selected countries, in 2015 and 2030: Now, the median age of the population—the point at which half the people are younger and half are older—is 45-plus in Italy, Germany, and Japan. Also, notice how high the median ages in these nations will be in 2030. How do you think living in these “most-aged nations” will affect residents’ daily lives?

Data from: Kinsella & Velkoff, 2001.

How will you feel about living in a nation where the people with walkers may be about to outnumber the babies in strollers on your streets? For hints, you might take a trip to a U.S. city where the age storm has struck. In Sarasota, Florida, where the 65-plus population tops 30 percent, residents view age 70 as “young.” You aren’t defined as elderly until you make it to age 80 and above (Fishman, 2010). In Sarasota, people understand: Statistically speaking, there is a world of difference between being healthy and young-old and having physical frailties (or depending on those walkers) during the old-old years.

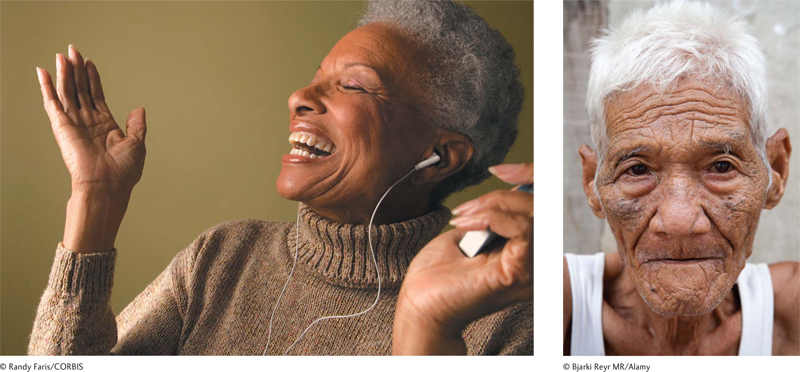

The health (and wealth) differences between the young-old and old-old may explain our contradictory stereotypes about later life. We have the image of the vital, energetic widow dating on-line, and the vision of the lonely, aged person languishing in a nursing home; the portrait of an affluent, retired married couple traveling the world, and picture of the depressed institutionalized elder with a dementing disease.

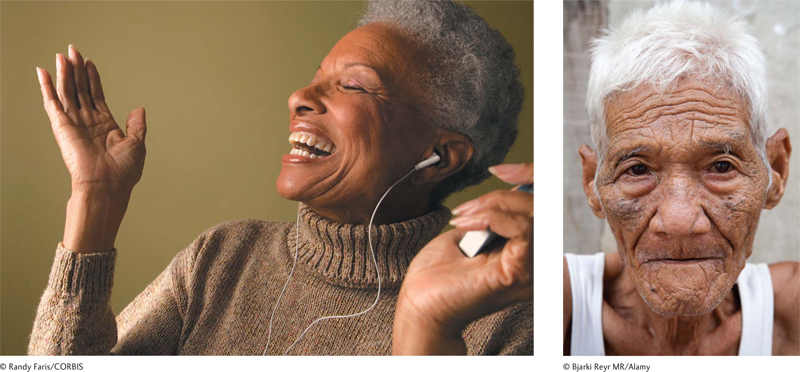

The expressions on the faces of this joyous 65-year-old and dour 90-year-old say it all. In terms of lifestyle, personality, memory, health, and everything else, there can be a world of difference between being young-old and old-old.

© Bjarki Reyr MR/Alamy

But amid this diversity lies consensus about the negative qualities related to being old. Worldwide, people link old age with physical and mental decline. While people in places like Sardinia, Italy, where the elderly have reputations for living healthy to the end of life, have more upbeat attitudes (Bottiroli and others, 2013), if you ask most older adults to forecast their futures, you are apt to hear gloomy comments such as, “I won’t be as happy in five years as I am today” (Lang and others, 2013).

The bottom line is that everyone—young and old—is guilty of ageism, intensely negative attitudes about old age, although among emerging adults this aversion varies depending on personality traits such as openness to experience or whether a young person is phobic about physical decline (Allan, Johnson, & Emerson, 2014). Moreover, as the Experiencing the Lifespan box shows, in contrast to our stereotypes, throughout history, old age has also been feared as a time of unremitting loss. Luckily, we also gravitate to the elderly for classic positive traits.

Experiencing the Lifespan: Ageism Through the Ages

The hair is gray. . . . The brows are gone, the eyes are blear . . . The nose is hooked and far from fair. . . . The ears are rough and pendulous. . . . The face is sallow, dead and drear. . . . The chin is purs’d . . . the lips hang loose. . . . Aye such is human beauty’s lot! . . . Thus we mourn for the good old days . . . , wretched crones, huddled together by the blaze. . . .

(excerpted from an Old English poem called“Lament of the Fair Heaulmiere” [or Helmet-maker’sgirl], quoted in Minois, 1989, p. 230)

Many of us assume that people had better values and attitudes toward old age in “the good old days.” Poems such as the one above show that we need to give that stereotype a closer look.

In ancient times, old age was seen as a miracle because it was so rare. Where there was no written language, older people were valued for their knowledge. However, this elevated status applied only to a few people—typically men—who were upper class. For slaves, servants, and women, old age was often a cruel time.

Moreover, just as today, cultures made a distinction between active, healthy older people and those who were disabled and ill. In many societies, for instance, the same person who had been revered was subjected to barbaric treatment once he outlived his usefulness—that is, became decrepit or senile. Samoans killed their elderly in elaborate ceremonies in which the victim was required to participate. Other cultures left their older people to die of neglect. Michelangelo and Sophocles, revered as old men, stand as symbols of the age-friendly attitudes of the nations in which they lived. However, the images portrayed in their creative works celebrated youth and beauty. Even in Classical Greece and Renaissance Italy—societies known for being enlightened—people believed old age was the worst time of life.

As historian Georges Minois (1989) concluded in a survey of how Western cultures treated their elders, “It is the tendency of every society to live and go on living: it extols the strength and fecundity that are so closely linked to youth and it dreads the . . . decrepitude of old age. Since the dawn of history . . . young people have regretted the onset of old age. The fountain of youth has always constituted Western man’s most irrational hope” (p. 303).

(The information in this box is taken from Minois, 1989, and Fischer, 1977.)

In one U.S. poll, adults agreed that a 75-year-old would be superior to a 20- something in calmly handling conflicts (Swift, Abrams, & Marques, 2013). When undergraduates were asked to discuss the personalities of audio recordings of speakers with “elderly” and “young” voices,” students did judge the old voices being less powerful. But they said they would gravitate to the elderly speakers for being gifted storytellers and being wise (Montepare, Kempler & McLaughlin-Volpe, 2014).

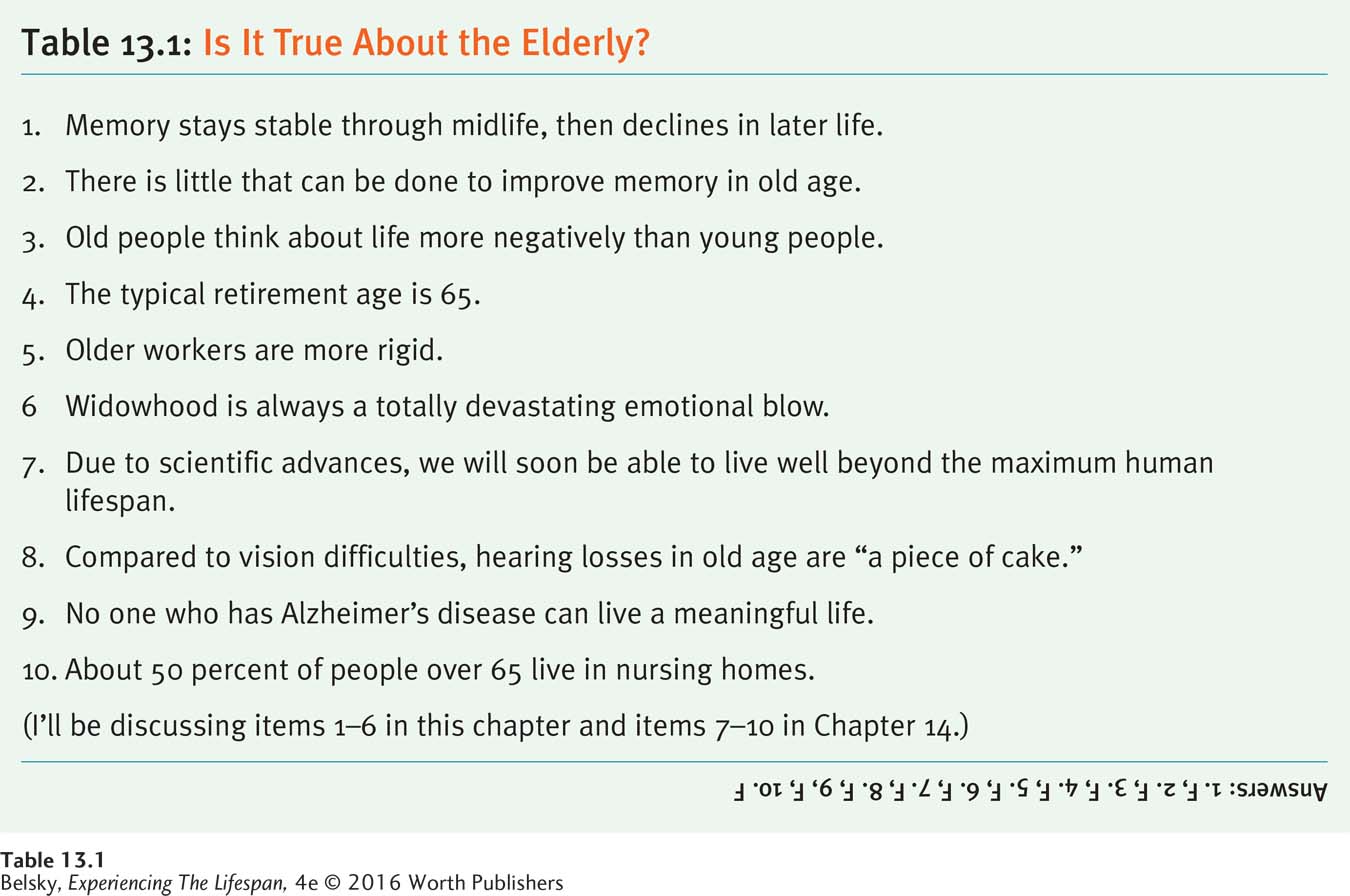

In these next two chapters, I’ll be giving you a wealth of scientific insights into our negative old-age stereotypes—as I chart the ways thinking and physical abilities decline in the older years. But as we enter the emotional lives of the elderly, I hope to give you a more positive image of your late life future, too. Do older people really have a mellower, more balanced, wise perspective on life? Before reading the research facts relating to this topic and others, you might want to explore your personal old-age stereotypes by taking the “Is It True About the Elderly” questionnaire (Table 13.1).