13.2 The Evolving Self

Now, let’s start our research tour, by first exploring how that important component of thinking, memory, changes during our older years, and then turning to the emotional quality of later life.

Memory

When we think of specific cognitive abilities, as we get older, we can look forward to positive changes—

In a classic study, psychologists demonstrated this mindset by filming actors aged 20, 50, and 70 reading an identical speech. During the talk, each person made a few references to memory problems, such as “I forgot my keys.” Volunteers then watched only the young, middle-

393

The reality is that, when a young person forgets something, we pass off the problem as due to external forces: “I was distracted”; “I had too much going on”; “It might be those four glasses of wine I had at dinner last night.” When that person is old, we have a more ominous interpretation: “Perhaps this is the beginning of Alzheimer’s disease” (Erber & Prager, 1999). When you last were with an elderly family member and she forgot a name or appointment, did the idea that “Grandma is declining mentally” cross your mind?

Scanning the Facts

Are older people’s memory abilities really much worse than those of younger adults? Unfortunately, the answer, based on thousands of studies, is yes. In testing everything from the ability to recall unfamiliar faces to the names of new places, from remembering the content of paragraphs to recalling where objects are located in space, the elderly perform more poorly than the young (see Dixon and others, 2007, for a review).

As a memory task gets more difficult, the performance gap between young and old people expands. When psychologists ask old people to recognize an item or word they have previously seen, they do almost as well as 20-

While connecting names to places, or remembering exactly where we heard some bit of information, is difficult in old age, this task is not easy at any life stage. I’ll never forget when a twenty-

The elderly do especially poorly on divided-

More depressing, when researchers pile on the memory demands and add time pressures, deficits show up as early as the late twenties (Borella, Carretti, & De Beni, 2008). Returning to the previous chapter, it makes sense that when people have to remember new, random bits of information very fast, losses take place soon after youth. These requirements are prime examples of fluid intelligence tasks.

What is going wrong with memory as we age? Let’s get insights from examining two different ways of conceptualizing “a memory”: the information-

394

An Information-

Remember from Chapters 3 and 5 that developmentalists who adopt an information-

Working memory, as I mentioned in Chapter 5, contains a limited memory-

What explains this decline? Experts target deficits with the executive processor, that hypothetical structure responsible for manipulating material into the permanent memory store. As people age, they have more problems with focusing this master controller and so can’t attend as well to what they need to learn (Müller-

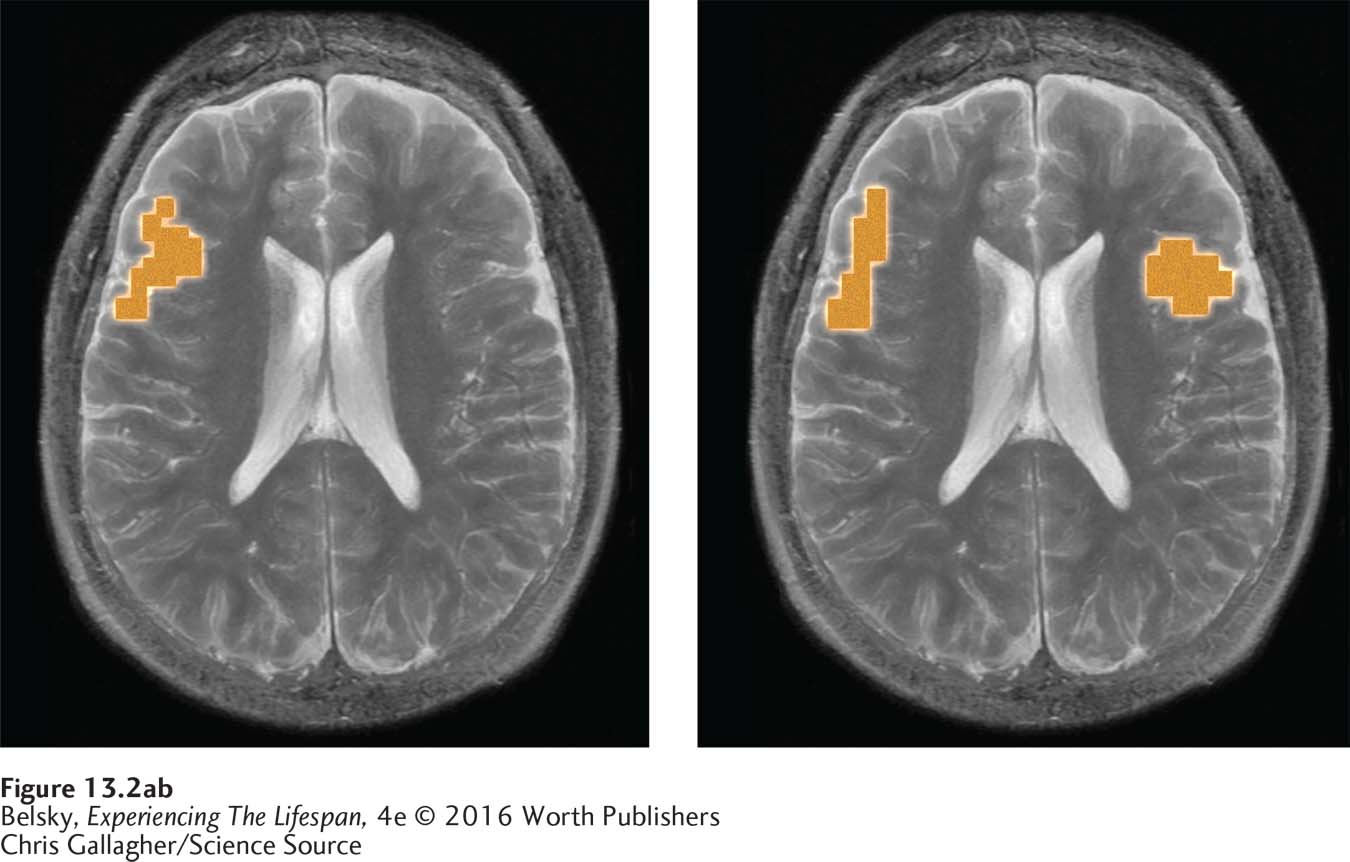

When we think of executive functions such as selective attention, a particular brain structure comes to mind. Later-

How does the older brain adapt? Because brain-

With easy memory challenges, such as remembering a few items, notice from Figure 13.2 that older adults show a broader pattern of frontal-

395

This finding is very depressing. Does the aging brain have to work on overdrive and then ultimately “give up” (neurologically speaking) in remembering everything? Luckily, the answer is no. Some memories are more indelibly carved in our mind.

A Memory-

Think of the amazing resilience of some memories and the incredible vulnerability of others. Why do you automatically remember how to hold a tennis racquet even though you have not been on a court for years? Why is “George Washington,” the name of our first president, locked in your mind while you are incapable of remembering what you had for dinner three days ago? These kinds of memories seem to differ in ways that go beyond how much effort went into embedding them into our minds. They seem qualitatively different in a fundamental way.

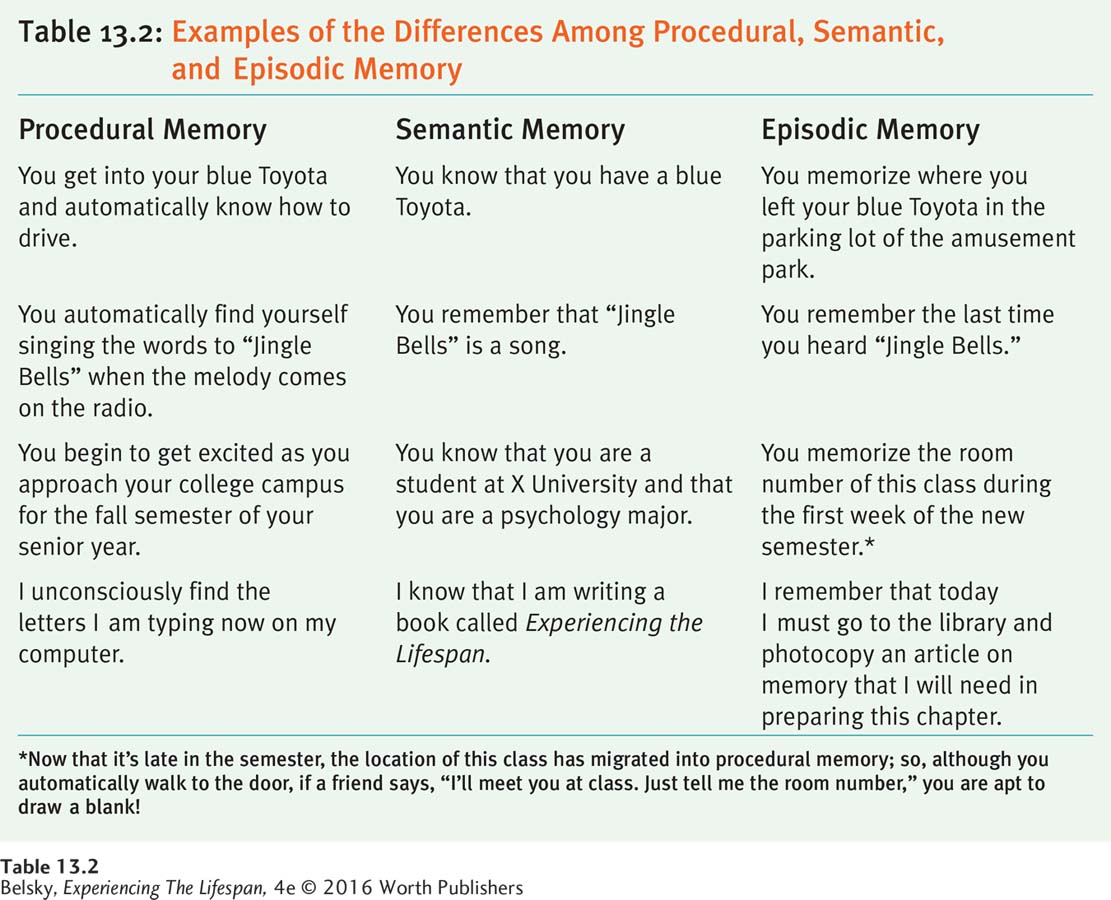

According to the memory-

Procedural memory refers to information that we automatically remember, without conscious reflection or thought. A real-

life example involves physical skills. Once we have learned a complex motor activity, such as how to ride a bike, we automatically remember how to perform that skill once we are in that situation again.

Semantic memory is our fund of basic factual knowledge. Remembering that George Washington was our first president and knowing what a bike is are examples of the kinds of information in this well-

learned, crystallized database.

Episodic memory refers to the ongoing events of daily life. When you remember going bike riding last Thursday or what you had for dinner last night, you are drawing on episodic memory.

As you can see in these examples and those described in Table 13.2, episodic memory is the most fragile system. A year from now you will still remember who George Washington is (semantic memory). You will recall how to get on the bike and use the handlebars to pace your speed (procedural memory). However, even a few days later, you are likely to forget what you had for dinner on a particular night. Remembering isolated events—

396

The good news is that on tests of semantic memory older people may do as well as the young (Dixon and others, 2007). Procedural memory is amazingly long-

This decline in episodic memory is what people notice when they realize they are having more trouble remembering the name of a person at a party or where they parked the car. Our databank of semantic memories stays intact until well into later life (Ofen & Shing, 2013)—explaining why we expect older people to outperform the young at crystallized verbal challenges such as crossword puzzles. People with Alzheimer’s disease can retain procedural memories after the other memory systems are largely gone. They can walk, dress themselves, and even remember (to the horror of caregivers) how to turn on the ignition and drive after losing their ability to recall basic facts, such as where they live.

The incredible resilience of procedural memory explains why your 85-

Actually, this is good. If I had to focus on remembering how to type these words on my computer, would I ever be able to simultaneously do the complicated mental work of figuring out how to describe the concepts I am explaining now?

In sum, the message with regard to age and memory is both worse and also far better than we might have thought: As we get older, we do not have to worry much about remembering basic facts. Our storehouse of crystallized knowledge is “really there.” However, we will have more trouble memorizing bits of new information, and these losses in episodic memory show up at a surprisingly early age.

INTERVENTIONS: Keeping Memory Fine-Tuned

What should people do when they notice that their ability to remember life’s ongoing details is worse? Let’s look at three approaches:

USE SELECTIVE OPTIMIZATION WITH COMPENSATION. The first strategy is to use Baltes’s three-

For example, to remember where you parked at the airport: (1) Focus on where you are parking when you slide your car into the spot. Don’t daydream or get distracted by the need to catch the plane. (2) Work hard to encode that specific location in your brain. (3) Take a photo on your smart phone so you won’t have to remember that place all on your own.

397

At this point, readers might be thinking: Why not just bypass those difficult executive-

USE MNEMONIC TECHNIQUES. Have you ever noticed that some episodic events are locked in memory (such as your wedding day or the time you and your significant other had that terrible fight), while others fade? Emotional events embed themselves solidly into memory because they activate wider regions of the brain (Dolcos & Cabeza, 2002). Therefore, the key to memorizing isolated bits of information is to make material stand out emotionally.

Mnemonic techniques are strategies to make information emotionally vivid. These approaches range from using the acronym OCEAN to help you recall the name of each Big Five trait in studying for the Chapter 12 test to, when introduced to the elderly woman in the photo below, thinking, “I’ll remember her name is Mrs. Silver because of her hair.”

The fact that we learn emotionally salient information without much effort may explain why our memories vary in puzzling ways in real life. A history buff soaks up every detail about the Civil War but remains clueless about where he left his socks. Because your passion is developmental science, you do well with very little studying in this course, but it takes you hours to memorize a single page in your biology text.

Actually, the principle that emotional events are locked more firmly in our brains may partly account for our impression that the elderly remember past experiences best. In fact, when researchers asked adults to remember self-

WORK ON THE PERSON’S MENTAL STATE. This brings up the thought that standard laboratory memory tests are unfair to older adults. These tests require remembering random bits of episodic information. So they showcase the very memory skill that dramatically declines with age. Wouldn’t the elderly do comparatively better when asked to remember emotionally salient information they need in their daily lives?

Now compound this bias with the poisonous impact of self-

Actually, just being told, “I’m giving you a memory test,” makes older people feel years older (Hughes, Geraci, & De Forrest, 2013). Moreover, labeling a test as “measuring memory” impairs an older person’s performance on any cognitive test. In one scary study, after being informed, “This is a memory test,” 70 percent of older adults scored below the clinical cut-

398

Moreover, subjective memory complaints (“I’m having terrible trouble remembering”) have a tenuous relationship to an older person’s actual scores on memory tests (Crumley, Stetler, & Horhota, 2014; Pearman, Hertzog, & Gerstorf, 2014). What does predict subsequent cognitive decline, one longitudinal study suggested, is depression—

So, to take a family example, when my 90-

Actually, in contrast to the image of late-

Personal Priorities (and Well-

Everyone believes that memory declines with age. But as I mentioned earlier, we have more positive ideas about our emotional lives. Does old age really bring serenity and emotional balance? Laura Carstensen believes it does.

Focusing on Time Left to Live: Socioemotional Selectivity Theory

Imagine that you are elderly and aware that you have a limited time left to live. How might your goals and priorities change? The idea that our place on the lifespan changes our life agendas is the premise of Carstensen’s socioemotional selectivity theory.

According to Carstensen (1995), during the first half of adult life, our push is to look to the future. We are eager to make it in the wider world. We want to reach a better place at some later date. As we grow older and realize that our future is limited, we refocus our priorities. We want to make the most of our present life.

Carstensen believes that this focus on making the most of every moment explains why late life is potentially the happiest life stage. When our agenda lies in the future, we often forgo our immediate desires in the service of a later goal. Instead of telling off the boss who insults us, we hold our tongue because this authority figure holds the key to getting ahead. We are nice to that nasty person, or go to that dinner party we would rather pass up in order to advance socially or in our career. We accept the anxiety-

In later life, we are less interested in where we will be going. So we refuse to waste time with unpleasant people or enter anxiety-

Furthermore, when our passion lies in making the most of the present, Carstensen argues, our social priorities shift. During childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood our mission is to leave our attachment figures. We want to expand our social horizons, form new close relationships, and connect with exciting new people who can teach us new things. Once we have achieved our life goals, we are less interested in developing new attachments. We already have our family and network of caring friends. So we center our lives on our spouse, our best friends, and our children—

399

Actually, as we travel throughout adulthood our social networks do shrink, and we center our lives more on family than friends (Wrzus and others, 2013). Moreover, perhaps partly due to years of experience managing complex social situations (see the previous chapter), the elderly report more positive interpersonal encounters than the young (English & Carstensen, 2014).

Older people, Carstensen finds, carefully limit their social encounters, too. When her research team asked elderly and young people, “Who would you rather spend time with—

When Do We Prioritize the Present Regardless of Our Life Stage?

But is this change in priorities simply a function of being old? The answer is no. Adults with fatal illnesses also voted to spend an evening with a familiar close person. So did people who were asked to imagine that they were about to move across the country alone. According to Carstensen, whenever we see our future as limited, we pare down our social contacts, maximize our positive experiences, and spend time with the people we care about the most.

Socioemotional selectivity theory explains why—

The theory accounts for the choices my cousin Clinton made when he was diagnosed with lymphoma in his early twenties. An exceptionally gifted architect, Clinton gave up his promising career and retired to rural New Hampshire to build houses, hike, and ski for what turned out to be another quarter-

Making the Case for Old Age as the Best Time of Life

This passion to make the most of every moment may partly explain the paradox of well-

OLDER PEOPLE PRIORITIZE POSITIVE EMOTIONAL STATES. This bias to focus on positive experiences, alluded to earlier, has been so well documented by now that it has its own label: the positivity effect. To take one example, imagine being at a casino and sitting next to an elderly adult. Carstensen’s research suggests the older person will be just as happy as you when she expects to win. But she probably won’t be upset (or will get far less disturbed) when she loses (Nielsen, Knutson, & Carstensen, 2008).

People of every age, as I described in the previous section, remember emotional stimuli best. However, the elderly perform better when asked to recall happy versus sad images and faces (Simon and others, 2013).

400

Older people also view their distressing life experiences in a less gloomy way. When asked to describe an upsetting event in their past, older adults used fewer negative emotions and described far less anxiety than did younger adults (Robertson & Hopko, 2013). When Carstensen’s research team had different age groups listen to stories about a 25-

If you need more evidence that age offers this serene bird’s-

OLDER PEOPLE LIVE LESS-

So knowing your life will end, and many years spent living, provide surprising emotional bonuses. Moreover, in old age, people have more luxury to do just what they want, and the outside world hassles them less!

What Can Make Old Age the Unhappiest Time of Life?

But at this point, many of you may be thinking, “Something is wrong with this picture.” What about the miserable elderly people who the world doesn’t treat so kindly, older adults left to languish, lonely and impoverished, in their so-

The erosion of U.S. retirement as a life stage (to be described in the next section) is destined to impair the emotional quality of old age. As “social connectedness” is critical to human happiness, widowhood and outliving friends must take a psychological toll. Now, combine this with the physical losses of advanced old age, and it should come as no surprise that some studies show happiness takes a nosedive as people approach the old-

So, the paradox of well-

401

Still, let’s not stereotype all ninety-

Experiencing the Lifespan: Jules: Fully Functioning at Age 94

It was a hot August morning at Vanderbilt University as friends, colleagues, and students gathered to celebrate the publication of his book. Their voices often cracked with emotion as they rose to testify: “You changed my life. You are an inspiration—

My parents left Europe right before the First World War. So in 1915, I was lucky enough to arrive in this world (or be born). Growing up in Baltimore, my brothers and I were incredibly close because, as the only Jewish family in our Christian immigrant neighborhood, we were living in an alien world. I vividly remember the neighborhood kids regularly taunting us as Jesus killers as we walked to school. So we learned from an early age that the world can be a dangerous place. What this experience did was to take us in the opposite direction . . . to see every person as precious, to develop attitudes that were worldwide.

When I was a teenager, and asked myself, “What is important in life?” the answer was “relationships,” . . . to have a fundamental faith in people. It was clear that human beings had a long way to go to reach maturity, but you need to act ethically and lovingly. I also looked to the Bible for guidance, asking myself, “What do the ancient prophets tell us about living an ethical life?” During the Second World War my brothers and I decided we could never participate in violence, and so we were conscientious objectors. I knew I could never kill another human being.

I started out my work life as a public school teacher in Baltimore. I had no desire to get a Ph.D., but when I read a paper by Carl Rogers* in 1948, who was developing his client-

I’m still the same person as always, the same adolescent hiding in the body of a 94-

It’s important never to put life in the past tense. There is no such thing as “aging” or “retirement.” You are always learning and developing. When I was younger and looked to the Bible for guidance, I gravitated to the prophet Micah. Micah sums up my philosophy for living in this one sentence: “What doeth the lord require of me but to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy god.”

*Rogers was one of the premier twentieth-

Decoding Some Keys to Happiness in Old Age

Do you have an old-

402

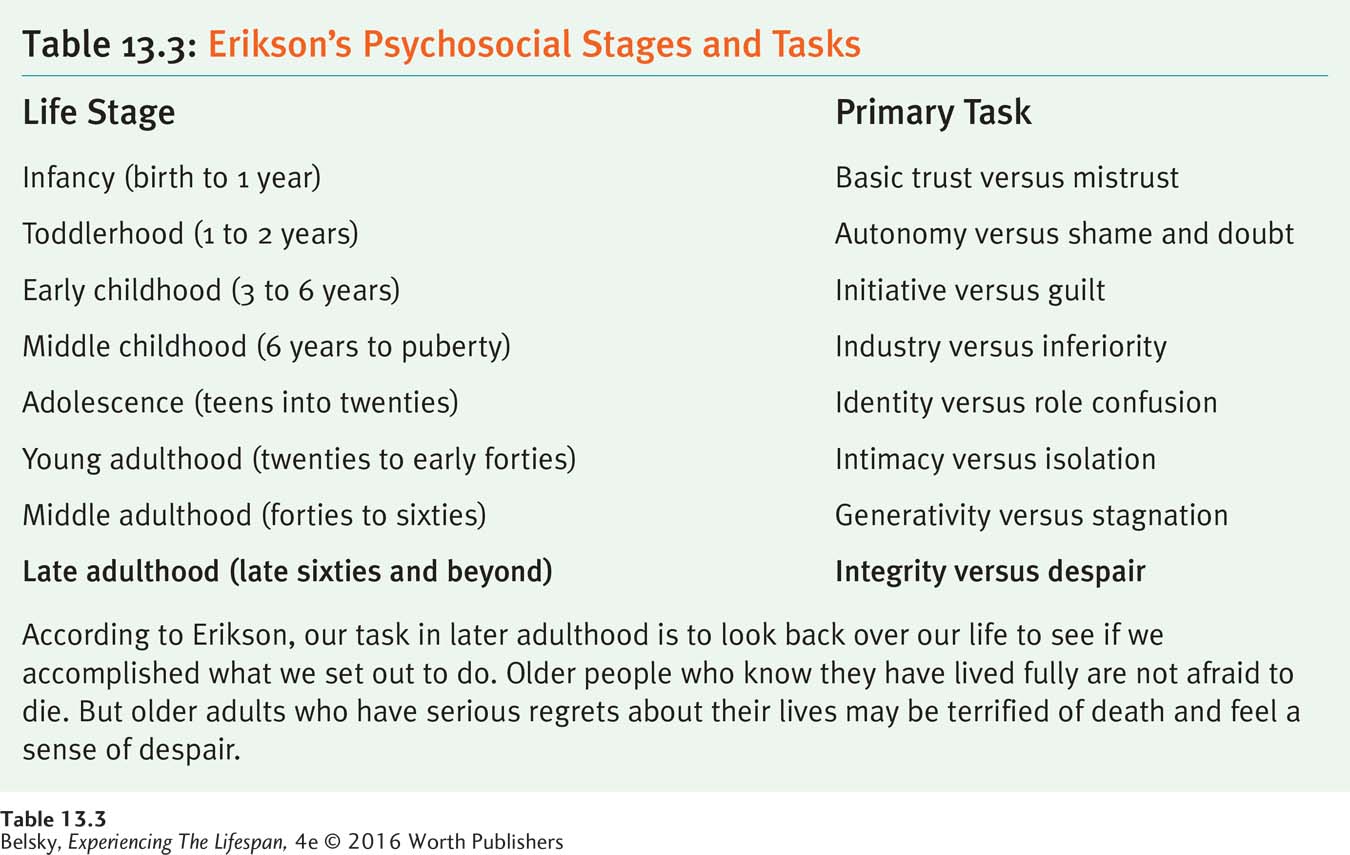

Erikson believed that, to reach integrity, older people must review their lives and make peace with what they have previously done. But, happiness in old age does not involve dwelling on the past. As with Jules, it involves finding purpose and meaning in your present life (Burr, Santo, & Pushkar, 2011).

Moreover, younger readers might be interested to know that, apart from everything else, having a sense of life purpose also predicts living longer. In one mammoth longitudinal study, adults of every age who agreed with questionnaire items such as, “I wander aimlessly through life,” died at earlier ages than their peers (Hill & Turiano, 2014).

By now you might be thinking that I am being far, far too positive. Clearly, people who remain upbeat emotionally and connected socially in advanced old age are rare. Not so fast! In four studies tracking Swedish people as they moved through their eighties, researchers did find specific groups declined dramatically cognitively or were isolated and depressed. But, the largest fraction of this oldest-

Live purposefully, be open to experience, remain lovingly attached, be generative—

INTERVENTIONS: Using the Research to Help Older Adults

Now, let’s summarize all of these messages. How can we help older people improve their memory skills? How should you think about the relationship priorities of older loved ones, and when should you worry about their emotional states? Here are some suggestions:

As late-

life memory difficulties are most likely to show up in situations where there is “a lot going on,” give older people ample time to learn material and provide them with a nondistracting environment (more about this environmental engineering in Chapter 14). 403

Don’t stereotype older adults as having a “bad” memory. Remember that semantic memory stays stable with age, and that teaching mnemonic strategies can work. Help older people develop their memory skills by suggesting this chapter’s tips. Also, however, be realistic. Tell the older person, “If you notice a decline in your ability to attend to life’s details (episodic memory), that’s normal. It does NOT mean you have Alzheimer’s disease” (Dixon and others, 2007).

Encourage older loved ones—

even those with disabilities— to maintain a personal passion. Being “efficaciously” engaged not only helps slide information through our memory bins, but makes for a happy life. Using the insights that socioemotional selectivity theory offers, don’t expect older people to automatically want to socialize or make new friends. When an elderly person says, “I don’t want to go to the senior citizen center. All I care about is my family,” she may be making an age-

appropriate response. Don’t imagine that older people are unhappy. Actually, assume the reverse is true. However, be alert to depression in someone who is physically frail and socially isolated. Again, the key to warding off depression in old age is the same as at any age: being generative, feeling closely attached, having a sense of meaning in life.

Tying It All Together

Question 13.1

Dwayne is planning on teaching lifespan development at the senior center. He’s excited; but since, until now, he’s taught only younger people, he’s worried about how memory changes in his older students might affect their enjoyment of his class. Based on your understanding of which memory situations give older people the most trouble, suggest some changes Dwayne might make in his teaching.

Dwayne should present concepts more slowly (but not talk down to his audience) and refrain from presenting a good deal of information in a single session. He should tie the course content into older adults’ knowledge base or crystallized skills and strive to make the material relevant personally. He might offer tips on using mnemonic techniques. He should continually work on reducing memory fears: “With your life experience, learning this stuff should be a piece of cake!”

Question 13.2

Classify each of the following memory challenges as involving episodic memory, semantic memory, or procedural memory:

Someone asks you for your street address.

Someone asks you what you just read in this chapter.

You go bike riding.

a. semantic memory b. episodic memory c. procedural memory

Question 13.3

Which of the abilities in the previous question (1) will an older loved one retain the longest if she gets Alzheimer’s disease, and (2) will start to decline relatively early in life?

1) Bike riding, that automatic skill, is “in” procedural memory, so it can be maintained even into Alzheimer’s disease. 2) Remembering the material in this chapter, since it is in the most fragile system (episodic memory), is apt to decline at a relatively young age.

Question 13.4

As you study this section, come up with a vivid image to embed the major terms in your mind. (For instance, to remember working memory, think of a brain on a treadmill; to recall episodic memory, think of an episode of your favorite TV show.) Do you agree that this optimization technique, while helpful, demands mental effort?

The answers here are up to you

Question 13.5

You are eavesdropping on three elderly friends as they discuss their feelings about life. According to socioemotional selectivity theory, which two comments might you hear?

Frances says, “Now that I’m older, I want to meet as many new people as possible.”

Allen reports, “I’m enjoying life more than ever today. I’m savoring every moment—

and what a pleasure it is to do just what I want!” Milly mentions, “I’ve been spending as much time as possible with my family, the people who matter to me the most.”

b and c

Question 13.6

Based on this chapter, give three reasons why happiness should peak in later life.

Older people (1) focus on enjoying the present, (2) selectively screen out negativity, and (3) live less-