13.3 Later-

404

Now, let’s look at how people find meaning as they confront the life transitions of retirement and widowhood.

Retirement

When we imagine the U.S. retirement age, we immediately think of 65. But, you might be surprised to know, the age for collecting full Social Security benefits is now 66 (and for people born after 1970, it will be 67); and for decades the “true” average U.S. retirement age was under 62 (Munnell & Rutledge, 2013). When we think of being retired, we imagine a short life stage before death. But if you leave work in your early sixties—

What caused retirement to take up such a huge chunk of the lifespan, and what is happening to this life stage in the United States today? Stay tuned as I scan the global economic retirement scene, and then offer a synopsis of current U.S. retirement trends.

Setting the Context: Differing Financial Retirement Cushions

If you are like many young people, you probably aren’t sure whether retirement will continue to exist once you reach later life. Actually, there are places where retirement doesn’t exist today. In Bangladesh, Jamaica, and Mexico, where more than half of all people over 65 are in the labor force, the elderly must work till they get seriously ill (Kinsella & Velkoff, 2001). The reason is that these nations lack the government-

By the late twentieth century, government-

What retirement programs can affluent nations provide? For answers, let’s compare Germany and the United States.

GERMANY: MERCEDES MODEL GOVERNMENT SUPPORT. Germans currently do worry more about retirement because they live in a rapidly aging nation where the government may need to cut back on the funds citizens have long enjoyed—

THE UNITED STATES: GOING IT ALONE WITH MODEST GOVERNMENT HELP. If Germany has offered a Mercedes-

Social Security, the landmark government program instituted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935 at the height of the Great Depression, gets its financing from current workers. Employees and employers pay into this program to fund today’s retirees; then, when it is their turn to retire, these adults get a lifelong stipend financed by the current working population. However, with an average monthly check of $1303 in late 2014, Social Security can barely support the basics of life for older adults (Social Security Monthly Statistical Snapshot, 2014).

405

Private pensions (and personal savings) are supposed to take up the slack. Workers put aside a portion of each paycheck, and these funds, often matched by employer contributions, go into a tax-

The central role of private pensions in financing retirement reflects the priority that the United States places on individual initiative. We are leery about the welfare-

Hot in Developmental Science: U.S. Retirement Realities

The problem is that, with an average retirement nest egg of $127,000, most baby boomers haven’t come close to amassing the pension cushion (at least 10 times that amount) to support a decent lifestyle for 15 or so years (Leicht & Fitzgerald, 2014; Collinson, 2014). Moreover, unfortunately, many adults have unrealistic impressions about their retirement futures, expecting help from family members or from pensions that are unlikely to exist (Whitaker & Bokemeier, 2014). What are the real retirement realities in the United States?

EXPECT LONGER WORKING LIVES. Hints come from asking people at the brink of retirement age. Less than one in nine baby boomers feel very confident they can retire with a comfortable lifestyle. Two out of three say they will work after age 65 (Collinson, 2014). In another poll, two in five people said they planned to work “til they drop” (reported in Leicht & Fitzgerald, 2014).

Why do people in the United States approach retirement so financially strapped? No, it’s not conspicuous consumption or an inability for this “entitled cohort” to live within their means. The real problem, social critics argue, lies in rising income inequality and the eroding loss in real wages (Leicht & Fitzgerald, 2014). When your salary has not been keeping pace with the cost of living for years, you simply don’t have the financial resources to save much for retirement. Now, combine this with the fact that, when the Great Recession hit in 2008, one in four people had their wages reduced or were laid off. Many baby boomers helplessly witnessed the value of their largest asset, their homes, erode.

In Chapter 10, I alluded to how the Great Recession has forced young people to postpone important events such as leaving the nest or getting married, in part because of the difficulty of finding decent jobs. But as a laid-

Moreover, even when baby boomers are fortunate to have well-

Where do women fit into this picture? As you might imagine, their less continuous work histories and lower-

406

EXPECT TO CONSIDER WORKING AFTER YOU RETIRE. These economic realities partly explain why two out of three retirees in the United States do return to work (Wang & Shi, 2014). Some people are fortunate to continue working for the same employer at reduced hours. Others search for less-

In Northern Europe, people who take post-

The dismal message is that, yes, U.S. retirement is becoming a shorter, more fragile phase of life. Moreover, the income inequalities highlighted throughout this book persist into the older years. Just as being single and female predicts earlier adult poverty, the same forces spell financial trouble in later life. But even formerly upper-

Now that we understand the U.S. landscape, it’s time to explore other influences that go into the decision to leave work.

Exploring the Complex Push/Pull Retirement Decision

Imagine that you are in your sixties and considering leaving your job. Clearly, your primary consideration is economic: “Do I have enough money?” However, a second force that comes into play in Western nations is health: “Can I physically continue at work?” (De Preter, Van Looy, & Mortelmans, 2013; Wang & Shi, 2014). There may be another, insidious influence prompting your decision: age discrimination.

THE IMPACT OF AGE DISCRIMINATION. Age discrimination in the United States is illegal. People cannot get fired for being “too old.” But because it’s acceptable to get rid of more expensive workers—

Encouraging retirement via a special buyout is the preferred positive route employers use to entice Western workers to “go gently” into their retirement years (Ekerdt, 2010). In fact, in Northern Europe, lavish pension incentives often made retiring at age 60 normal, because it didn’t make financial sense for people to continue to work (De Preter, Van Looy, & Mortelmans, 2013). But workers also disengage from their jobs when they identify with being “ older employees,” agree with the negative stereotypes attached to that category, and feel discriminated against at work (Bayl-

Older workers are supposed to be rigid, make more mental mistakes, be fearful of technology, and be less adaptable at work (McCann & Keaton, 2013). The problem is that these images are false! In one Swedish study, age made people more flexible at work (Kunze, Boehm, & Bruch, 2013). Research in the United States has suggested older workers are more compliant and, amazingly, less likely to take time off for being sick, in addition to generally being more reliable than younger employees (Newman, 2011).

Still, these facts don’t matter much when a laid-

407

THE IMPACT OF WANTING TO WORK LONGER OR RETIRE. So far, I’ve been focusing on the dismal forces that affect retirement: Financial problems keep people in the labor force unwillingly; health issues and age discrimination push people to retire. I’ve been neglecting the fact that the decision to keep working or retire is also a positive choice. Many baby boomers say they want to keep working after age 65 because they love their jobs (Adams & Rau, 2011; Galinsky, 2007). People may retire in order to enter an exciting, new phase of life.

Who is passionate to stay in the labor force until their seventies or up to age 85? As I implied earlier, these older adults are often healthy and highly educated workers, like Jules in the Experiencing the Lifespan box on page 401, who feel tremendous flow in their careers (Adams & Rau, 2011; Wang & Shi, 2014). What about adults who permanently retire? Are they depressed or thrilled after taking this step?

Life as a Retiree

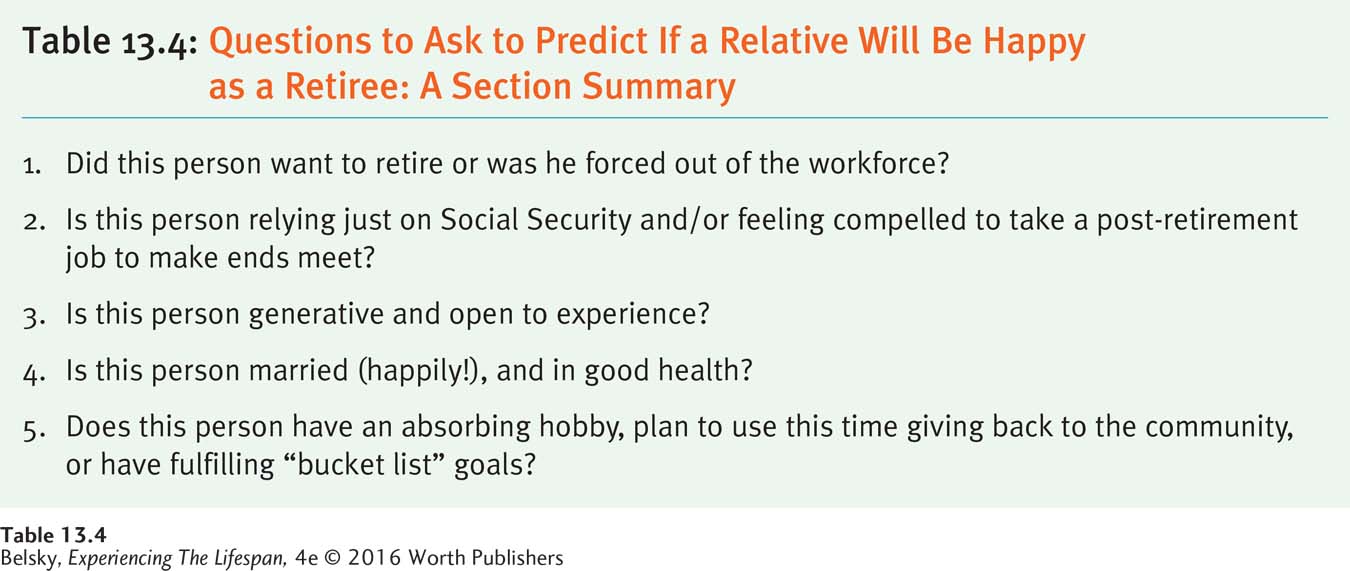

The answer is “it depends.” Retirement at age 65 typically has no effect on well-

Actually, the qualities that make for retirement happiness are identical to the attributes that make for a satisfying life at any age: Be open to experience, generative (Burr, Santo, & Pushkar, 2011), healthy, happily married, and have the economic resources to enjoy life (Pinquart & Schindler, 2007).

Having a serious leisure passion, such as playing the flute or volunteering at church, smooths the way to a satisfying retirement life (Heo and others, 2010). In an uncanny parallel to the research described earlier relating to life purpose, one research summary suggested that volunteering in later life significantly reduced a person’s risk of death (Okun, Yeung, & Brown, 2013). In fact, you can predict whether a just-

How can you expect your relative to spend these years? Because “personality endures,” one key is to look to her passions now (Atchley, 1989; Pushkar and others, 2010). So, a social activist joins the Peace Corps. A business executive volunteers at SCORE (Senior Corps of Retired Executives), advising young people about setting up small businesses. Others decide to take up new “bucket list” goals such as hiking the Himalayas or getting a history Ph.D. Many people open to experience might retire to pack in as much new learning as they possibly can.

408

A dazzling menu of options are available to older adults passionate to expand their minds, from reduced fees at colleges, to older-

As my goal and the life agendas of millions of baby boomers reveal, in the Western world, we see the older years as a time to vigorously connect to the world (Ekerdt, 1986). However, there is a different cultural model of retirement. In the traditional Hindu perspective, later life is a time to disengage from worldly concerns. Ideally, people become wandering ascetics, renouncing their connections to loved ones and earthly pleasures in preparation for death (Savishinsky, 2004). Although this plan is rarely followed in practice (after all, our need to be closely attached is a basic human drive!), let’s not assume that our “do not go gently into the sunset,” keep-

Summing Things Up: Social Policy Retirement Issues

Now, let’s summarize these section messages by focusing on some critical social issues with regard to retirement.

Retirement is an at-

risk life stage. In the United States, the lack of pension income and other assets is the immediate threat to retiring at 65. But the other issue lies in probable future cutbacks in Social Security (perhaps an increase until age 70 for receiving full benefits, or declining support levels). In 1950, there were about 16 workers for every U.S. retiree. Soon, the old- age dependency ratio, or proportion of working adults to retirees, will decline to almost 2 to 1 (Johnson, 2009). Social Security was never intended to finance a stage of life. It was instituted during a time when life expectancy was far shorter, as a stopgap for when health issues made it impossible to work. Now that the age of eligibility for full Social Security benefits is rising to 67, what other changes (retrenchments) will be on the horizon when the baby boomers have all stormed into later life? Older workers are (currently) an at-

risk group. From being offered incentives to retire early, to not hiring older workers— age discrimination at work is alive and well (Ekerdt, 2010; Neumark, 2009). But, the situation is changing. Anxious about their shrinking labor force, European employers are taking steps to reverse their decades- long practice of enticing older people to leave work via pension perks (van Selm & Van der Heijden, 2013). While the United States still has ample young workers to float its economy, this may not be true in another decade when the mammoth baby boom cohort all reaches 65. At that time, will U.S. employers also change their negative attitudes toward hiring older employees? Older people are more at risk of being poor. During the 1960s and 1970s, the United States took the landmark step of dramatically reducing poverty among older adults. Congress extended Social Security benefits. Our nation passed that crucial government-

funded health- care program called Medicare. (You can see the dramatic effects of these programs in cutting elderly poverty- rates by turning back to Figure 4.6, on page 118.) Old- age economic hardship is currently the fate for the roughly 1 in 3 retired Americans who survive on Social Security alone (Binstock, 2010), for the many people who must keep working during their so- called golden years, and for an alarming percentage of women as they reach advanced old age. Will poverty become endemic among the over- 65 population in future years?

Finally, I can’t leave the topic of old-

409

Widowhood

Although we worry about its future, most of us associate retirement with joy. That emotion does not apply to widowhood. In a classic study of life stress, researchers ranked the death of a spouse as life’s most traumatic change (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). What multiplies the pain is that today, widowhood still may strike a pre-

Imagine losing your life partner after 50 or 60 years. You are unmoored and adrift, cut off from your main attachment figure. Tasks that may have been foreign, such as understanding the finances or fixing the food, fall on you alone. You must remake an identity whose central focus has been “married person” for all of your adult life. Decades ago, British psychiatrist Colin Parkes (1987) beautifully described how the world tilts: “Even when words remain the same, their meaning changes. The family is no longer the same as it was. Neither is home or a marriage” (p. 93).

How do people mourn this loss? Who has special trouble with this trauma, and how can we help people cope? Let’s look at these questions one by one.

Exploring Mourning

During the first months after a loved one dies, one classic study showed, people are often obsessed with the events surrounding the final event (Lindemann, 1944; Parkes, 1972). Especially if the death was sudden, husbands and wives report repeatedly going over a spouse’s final days or hours. They may feel the impulse to search for their beloved, even though they know intellectually that they are being irrational. Notice that these responses have similarities to those of a toddler who frantically searches for a caregiver when she leaves the room. With widowhood—

Experiencing the Lifespan: Visiting a Widowed Person’s Support Group

What is it like to lose your mate? What are some of the hardest things to endure in the first year after a spouse dies? Here are the responses I got when I visited a local support group for widowed people and asked the women these kinds of questions:

“I’ve noticed that even when I’m with other people, I feel lonely.”

“I find the weekends and evenings hard, especially now that it gets dark so early.”

“Sundays are my worst. You sit in church by yourself. People avoid you when you are a widow.”

“I think the hardest thing is when you had a handyman and then you lose your handyman. You would be amazed at how much fixing there is that you didn’t know about. My hardest jobs were George’s jobs. For instance, every time I have a car problem I break down and cry.”

“I was married to a handyman and a cook. He spoiled me rotten. You don’t realize it until they are gone.”

“For me, it’s the incessant doctors’ bills. I got one yesterday. It’s that continual painful reminder of the death.”

“And you get all this stuff from Medicare, from Social Security. This year will be the last I file with him.”

“You just don’t know what to do. I didn’t know anything, didn’t know how much money we had . . . didn’t know about the insurance. . . . My family would help me out but, you know, it’s funny—

“You have friends, but you can’t really talk to them. You don’t bring him up, and neither does anyone else.”

“The thing that upsets me is that I’m scared that no one but me will remember that he was alive.”

410

Experts dislike using the word “recovery” to describe bereavement, as it implies that mourning, a normal life process, is a pathological state (Sandler, Wolchik, & Ayers, 2008). Moreover, when people lose a spouse, they do not simply “get better.” They emerge as different, hopefully more resilient human beings (Balk, 2008a, 2008b; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2008). Still, as I will describe in Chapter 15, after about a year, we expect widowed people to “improve” in the sense of remaking a satisfying new life. People still care deeply about their spouses. Their emotional connection remains. However, this mental image is incorporated into the survivor’s evolving identity as the widowed person continues to travel through life.

Now, let’s survey the research messages we get from tracking people’s feelings as they move from early bereavement into what attachment theorists might label the working model—

WIDOWHOOD INVOLVES FLUCTUATING EMOTIONS. Interestingly (and in contrast to the image of unremitting pain), one conclusion of these studies is that widowhood evokes contradictory emotions. In following 59 widows, psychologists charted a regular decline in depressive symptoms over time. However, life satisfaction scores showed a different pattern, dipping to a low at the first year anniversary, and then rising during the second year (Powers, Bisconti, & Bergeman, 2014). Other researchers, following a huge national sample of Australian adults, found that, after widowhood, there was a rise in well-

What could explain this embarrassing finding? One possibility is that, as you saw in the introductory chapter vignette, even people in the happiest long-

This is not to minimize the health consequences of widowhood. Study after study finds that, compared to married adults, the widowed have worse mental health (Choi and Vasunilashorn, 2014; Sasson & Umberson, 2014). In one alarming Canadian finding, 2 in 5 elderly people showed chronic symptoms of depression after losing a husband or wife (Jozwiak, Preville, & Vasiliadis, 2013). The most powerful example comes from the widowhood mortality effect—a markedly higher risk of dying for the surviving spouse after a partner dies (Sullivan & Fenelon, 2014). Who can people most rely on for support during this difficult time?

FRIENDS SEEM MORE IMPORTANT THAN CHILDREN IN DETERMINING HOW PEOPLE ADJUST. Actually the surprising answer is friends. Family members do get people over the initial bereavement hump. But, because they have their own lives, children may need to move on (“Now that it’s been three months, I don’t need to visit Mom every day. I have to take care of my own husband and kids”). Therefore, to cope effectively over the long term, widows need to reach out to friends (Ha & Ingersoll-

The virtue of friends is that, not only are they companions with whom to share activities, they also may allow you to more openly share your distress. For instance, in one study, Chinese widows living in Canada felt it was inappropriate to discuss their grief with family members (Martin-

411

At this point, readers may be tempted to urge everyone who has lost a spouse to join a widowed person’s group. This may be a mistake. An underlying message of my discussion is that most widowed people are resilient. We are doing them a disservice by assuming they are incompetent and totally in need of help. Actually, support groups for widowed people, psychologists find, are useful mainly for people who are having unusual trouble coping with this life event (Bonanno & Lilienfeld, 2008; Onrust and others, 2010). Who has special trouble coping with widowhood?

Predicting Which Widowed Adults Are Most at Risk

Some of you might imagine that men should be most vulnerable to having serious problems after their spouse dies. Women are more emotionally embedded in relationships. They can use their close, enduring connections with friends to construct new lives. Imagine losing your only attachment figure and you will understand why, for elderly widowers living alone, suicide is a major concern (Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007).

Still, men have one great advantage over women in the reattachment odds—

Another general risk factor, we might think, relates to whether the death was predicted or struck out of the blue (Schaan, 2013). Did your husband die unexpectedly on the golf course or pass away after years of worsening health? On-

Perhaps because males might be losing their only attachment figure, one study exploring the widowhood mortality effect showed husbands whose wives died unexpectedly were at much higher risk of dying than other widowed adults (Sullivan & Fenelon, 2014). In contrast, other researchers (Sasson & Umberson, 2014) found losing a spouse hits women harder when that event happens at an off-

However, rather than making generalizations based on gender or age, again, in predicting reactions to widowhood we need to adopt a developmental systems approach—

412

We also can’t neglect the role of the wider environment. Widowhood can be a more devastating blow for working-

Finally, we also need to look to the way a given culture treats widowed people. To take an extreme case, let’s travel to a place where being widowed (for women) can have nightmarish aspects that go well beyond losing a spouse.

Among the Igbo of West Africa, new widows must “prove” that they did not kill their spouse by sleeping with their husband’s corpse. Because property rights revert to the paternal side of the family, after the man’s death, his relatives feel free to take the bereaved woman’s possessions and force her off her land (Cattell, 2003; Sossou, 2002). Given this totally male-

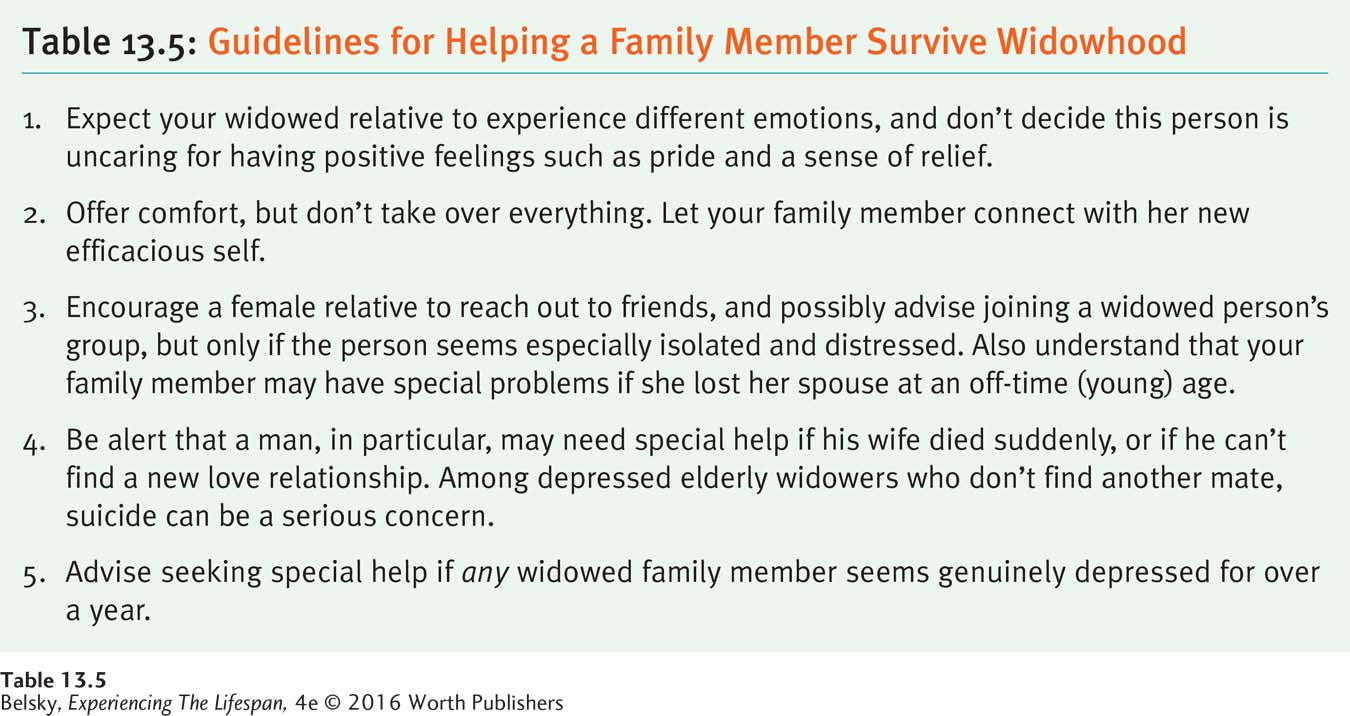

Table 13.5 pulls together the main points of my discussion in guidelines for helping a widowed family member. As a final comment, if you are a child, please allow your widowed parent to develop a new romantic attachment! You might think that new relationships run into headwinds from children mainly after parents’ divorce (see Chapter 11). But, in the dating in late life study I alluded to earlier, when father–

In the next chapter, devoted to the physical challenges of later life, I’ll be continuing this discussion by offering tips about how to sensitively treat loved ones, especially during the old-

Tying It All Together

Question 13.7

413

Joe, a baby boomer, is approaching an age when he might retire from his public school teaching job. Compared to a colleague who retired a decade ago, Joe (pick false statement): (a) is apt to have lower retirement assets (due to the 2008 recession); (b) will probably retire at an older age; (c) may need to work after he does retire; (d) will be unhappy if he devotes retirement to volunteering with at risk kids.

d

Question 13.8

Social Security provides a lavish/meager income that is guaranteed by the government/depends on personal investments.

meager/guaranteed

Question 13.9

As I touched on in the text, to preserve Social Security, U.S. readers are apt to hear discussions about increasing the age of eligibility for getting full benefits to age 70. Discuss the pros and cons of this controversial idea.

Pros: Raising the retirement age to 70 will keep Social Security solvent, encourage older people to be productive for longer, and get society used to the fact that people can function competently well into later life. Cons: Depriving people of this money will add to the pressure forcing older people to unwillingly keep working—

Question 13.10

If your favorite aunt’s husband recently died, you can expect (choose one): mixed feelings of loss and self-

You can expect mixed feelings of intense loss and self-