14.1 Tracing Physical Aging

418

Susan has atherosclerosis, or fatty deposits on her artery walls. Her fragile bones and vision and hearing problems are also classic signs of normal aging—body deterioration that advanced gradually over years. Over time, normal aging shades into disease, then disability, and, finally—

PRINCIPLE #1 CHRONIC DISEASE IS OFTEN NORMAL AGING “AT THE EXTREME.” Many physical losses, when they occur to a moderate degree, are called normal. When these changes become extreme, they have a different label: chronic disease. Susan’s bone loss and atherosclerosis are perfect examples. These changes, as they progress, produce those familiar later-

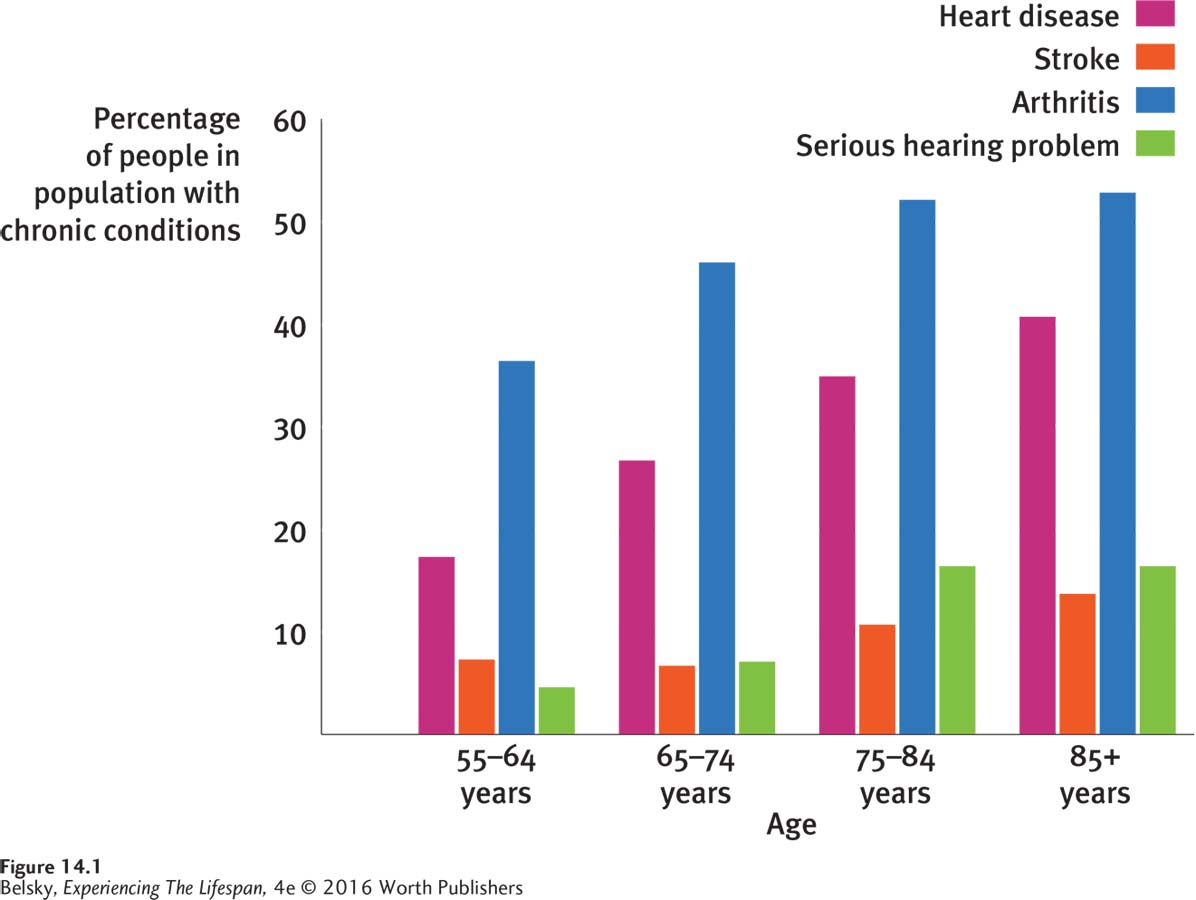

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), an annual government poll of health conditions among the U.S. population, tells us other interesting illness facts. As you can see in Figure 14.1, arthritis is the top-

PRINCIPLE #2 ADL IMPAIRMENTS ARE A SERIOUS RISK DURING THE OLD-

419

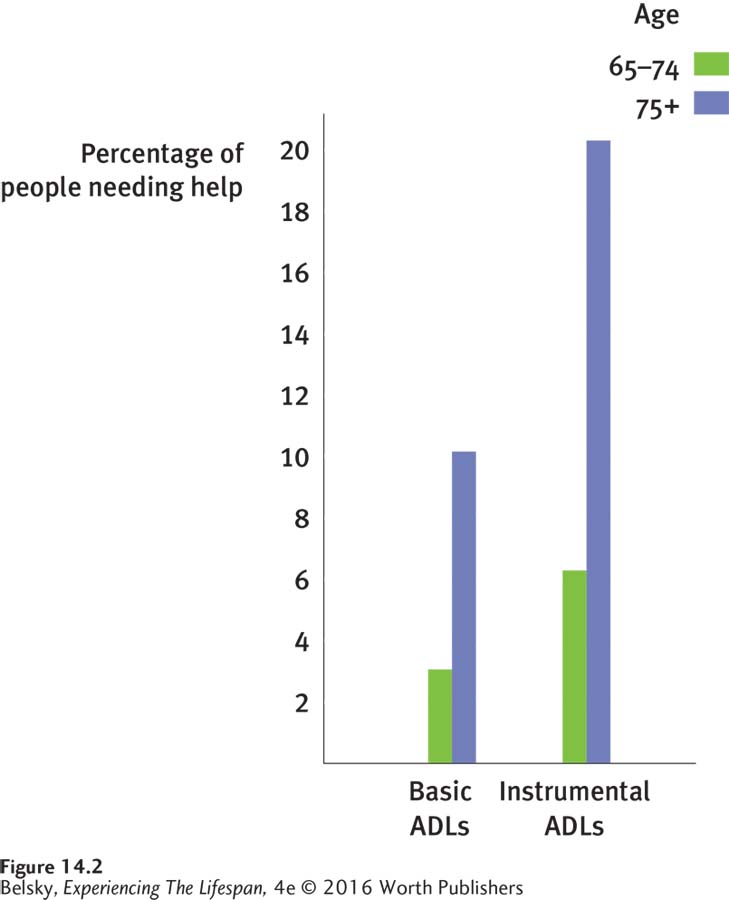

Although ADL problems can happen at any age, notice from Figure 14.2 that the old-

So, yes, people can arrive at age 85 or 90 virtually disability free. But as we travel further into later life, problems physically coping become a serious risk.

PRINCIPLE #3 THE HUMAN LIFESPAN HAS A DEFINED LIMIT. A final fact about aging is that it has a fixed end. More people than ever are surviving past a century. But a miniscule fraction make it beyond that barrier age. In August 2014, worldwide, there were roughly 75 documented “super-

Can We Live to 1,000?

At this point, you might be thinking that many babies will soon make it to be supercentenarians. Due to scientific breakthroughs in extending the lifespan, you may have read the world is poised for the arrival of the first 1,000-

420

These futuristic forecasts fall on fertile ground because one life-

Calorie restriction is actually an all-

Without denying that it’s important to watch your diet, however, restricting your intake just to live to 110 is a mistake. The calorie reduction research has typically been carried out with rats. The scientific literature is littered with miracle disease-

Calorie restriction has confusing effects. Sometimes it postpones deaths in youth or allows just a small number of the most long-

Let’s listen to the foremost experts in the biology of aging explain why extending the maximum lifespan in the near future is an unrealistic dream (Carnes, Olshansky, & Hayflick, 2013):

The body breakdown involved in aging has complex causes, from multiple genetic timers to random insults that happen as cells do their metabolic work. There can’t be a single magic-

bullet intervention that stops aging and extends life. Even if a breakthrough technology such as stem- cell research fulfills its promise to regenerate cells lost to Parkinson’s disease (Kim, Lee, & Kim, 2013), a few years later some other age- related illness, like cancer, is going to crop up. The best analogy to our aging bodies is an old car. Replacing each defective part only puts off the day when so much goes wrong that the whole system reaches its expiration date and everything stops. Our body’s evolutionary expiration date is naturally set well below a century, because the survival of our species promotes, at best, living through the grandparent years (recall Chapter 12). Therefore, even in the most affluent nations, the probability of a twenty-

first- century newborn living to 100 remains low. (It’s about 4.5 percent in Japan.) So, let’s celebrate our remarkable twentieth- century progress at allowing most babies born in the developed world to survive close to our expiration date. But, let’s realize that extending the maximum lifespan is going to be far harder than the breakthroughs that allowed us to make it to later life.

Now let’s turn to two familiar markers that affect our journey toward our expiration date (and every other aspect of our lifespan journey): socioeconomic status and gender.

Socioeconomic Status, Aging, and Disease

The most powerful evidence that poverty affects how long we live comes from scanning a few life-

421

When, during adulthood, is the socioeconomic health gap most pronounced? The answer, according to most (but not all) surveys, is during midlife, as normal age changes are progressing to chronic disease. For instance, in one study in Holland, only 5 percent of people in the top quarter of the income distribution reported being in poor health at age 55. For their bottom quarter counterparts, the odds were 1 in 3 (Kippersluis and others, 2010).

You may see these statistics in operation by just looking around. Notice how, by the late thirties people show clear differences in their aging rates. Although there are many exceptions, notice also that low-

How far back in development can we trace this accelerated aging path? Unfortunately, based on the fetal programming hypothesis, its roots might emerge in the womb. Remember from Chapter 2 that low birth weight—

Now compound this with the poisonous adult lifestyle forces linked to poverty—

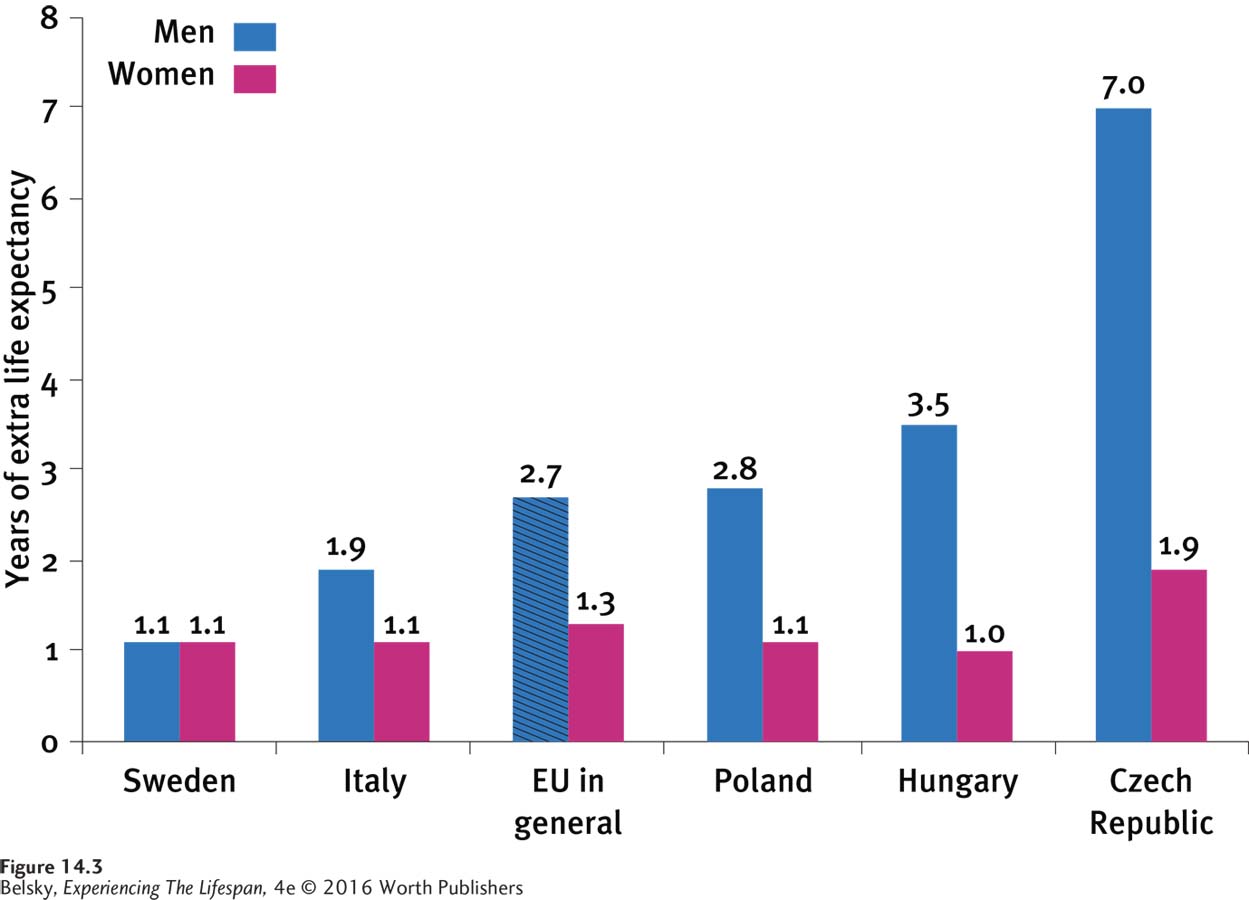

So far, I’ve spelled out a dismal scenario. But, socioeconomic status involves both education and income. And, as you will see in Figure 14.3 below, the educational component of SES looms large in predicting life expectancy, especially for men (OECD, 2014; Mazzonna, 2014).

Fascinating evidence that education directly affects aging involves research on telomeres, DNA sequences at the end of our chromosomes. Telomere shortening is a benchmark of cellular aging, as it shows that a particular cell has reached senescence and can no longer divide. Among a huge group of U.S. older adults, researchers found that high school graduates had shorter telomeres than people who attended college, a difference that was particularly striking among Black men (Adler and others, 2013; Mazzotti, Tufik, & Andersen, 2013). Therefore, in addition to (or due to) its other benefits, college can extend our lives!

422

Another life extender is close relationships. In one landmark study, researchers found that caring social connections were as—

Being embedded in nurturing communities may explain “the Hispanic paradox,” the fact that poverty-

Gender, Aging, and Disease

Their wider web of social connections could be one reason why women outlive men, sometimes by an incredible decade or more (OECD, 2014). Still, the main reason for women’s superior survival is biological. Having an extra X chromosome makes females physically hardier at every stage of life.

During adulthood, the main reason for this gender gap can be summed up in one phrase: fewer early heart attacks. Illnesses of the cardiovascular system (the arteries and their pump, the heart) are the top-

Their biological susceptibility to early heart attacks means that men tend to “die quicker and sooner.” For women, the worldwide pattern is “surviving longer but being more frail” (OECD, 2014; Tareque, Begum, & Saito, 2013; Rohlfsen & Kronenfeld, 2014; Onadja and others, 2013).

423

It makes sense that disability is the price of traveling to the lifespan train’s final stops. However, the phrase “living sicker” applies to women throughout adult life. During their twenties and thirties and forties, only women experience the physical ailments related to pregnancy and menstruation. As they age, females have higher rates of arthritis, vision impairments, and obesity—

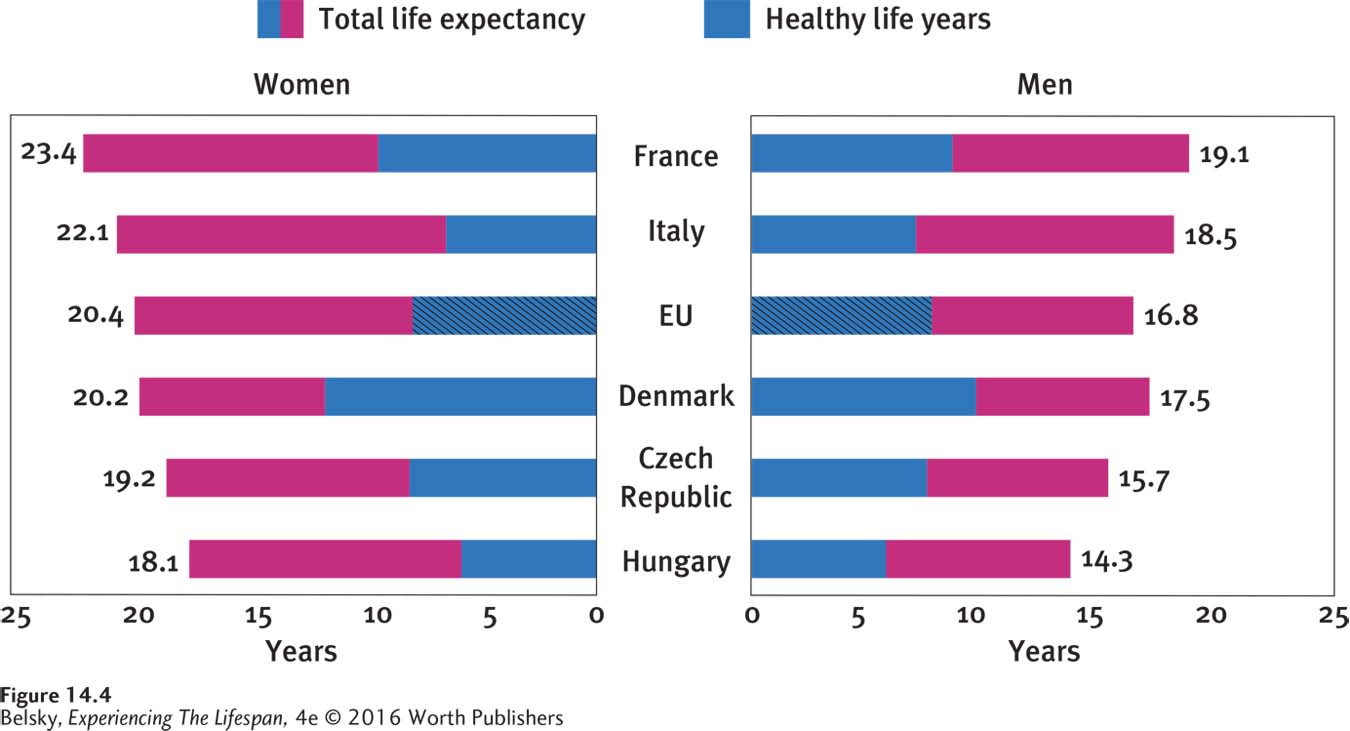

This male/ female disability distinction brings me to a statistic called healthy-

INTERVENTIONS: Taking a Holistic Lifespan Disease-Prevention Approach

How can we increase our healthy-

Focus on childhood. As I’ve been stressing throughout this book, we need to prevent premature births, make inroads in child poverty, and improve early childhood education. Now we understand that encouraging teens to enroll in and finish college can also have health benefits in middle and later life!

Focus on constructing caring communities. Let’s commit to making cities senior-

citizen friendly (Barusch and others, 2013); and construct walkable, planned communities that allow people to exercise without going to gyms. Let’s build in services that reach out to isolated neighbors and provide the nurturing social relationships that extend life.

Finally, let’s appreciate the realities in Figure 14.4. Without minimizing old age’s emotional benefits, even in the most health-

424

Tying It All Together

Question 14.1

When she was in her late fifties, Edna’s doctor found considerable bone erosion and atherosclerosis during a checkup. At 70, Edna’s been diagnosed with osteoporosis and heart disease. Did Edna:

suddenly develop these diseases?

have normal aging changes that slowly progressed into these chronic diseases?

have both above events occur?

b

Question 14.2

Marjorie has problems cooking and cleaning the house. Sara cannot dress herself or get out of bed without someone’s help. Marjorie has_____ problems and Sara has_____ problems.

Marjorie has instrumental ADL problems, and Sara has basic ADL problems.

Question 14.3

Laura brags that her newborn is likely to live to 120. Using the points in this section, convince Laura that she is wrong.

Tell Laura that physical aging has such complex causes that finding any single life-

Question 14.4

Nico and Hiromi are arguing about men’s versus women’s health. Nico says that women are basically “healthier”; Hiromi thinks that it’s men. Explain why both Nico and Hiromi are each partly correct.

Nico and Hiromi are both correct, because although women live longer (meaning that they must be healthier), they also live “sicker” (meaning that they are more apt to be ill) throughout adulthood.