Our Windows on the World: Vision

One way aging affects our sight becomes evident during midlife. By their late forties and fifties, people have trouble seeing close objects. The year I turned 50, this change struck like clockwork, and I had to buy glasses to read.

Presbyopia, the term for age-related difficulties with seeing close objects, is one of those classic signs, like gray hair, showing that people are no longer young. When I squint to make out sentences, the fact of my age crosses my consciousness. I imagine students have this same thought (“Dr. Belsky is older”) when they see me struggle with this challenge in class.

Other age-related changes in vision progress gradually. Older people have special trouble seeing in dim light. They are more bothered by glare, a direct beam of light hitting the eye. They cannot distinguish certain colors as clearly or see visual stimuli as distinctly as before.

What is it like to be undergoing this progression? It can be annoying to ask the server what the impossibly faint restaurant bill comes to or to fumble your way into a neighbor’s seat at a darkened movie theater. For me, the most hair-raising experiences relate to driving at night. Last week, a curve of the highway exit ramp loomed out of the dark and I was inches from death. But apart from worries about night driving these problems have little effect on my life.

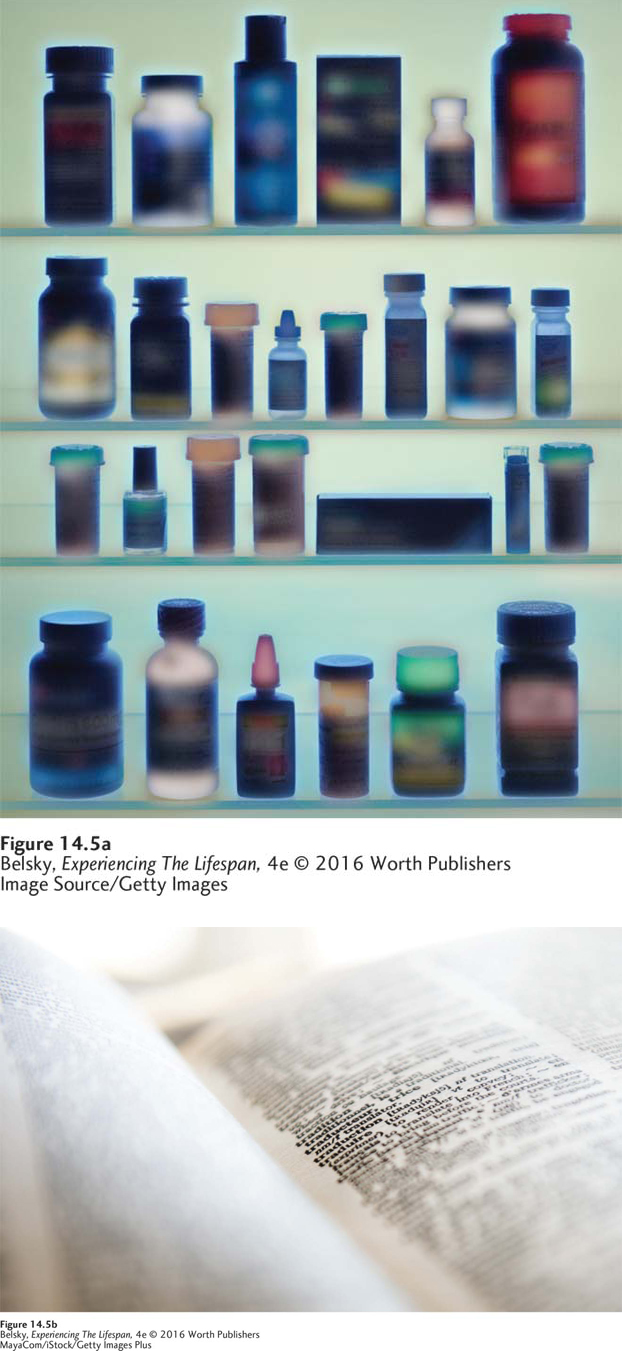

Unfortunately, this may not be true a decade from now. As Figure 14.5 illustrates, seeing in glare-filled environments such as a lighted medicine cabinet, or even making out the print on a white page, can be a real challenge during the old-old years.

Figure 14.5: How an 85-year-old might see the world: Age-related visual losses, such as sensitivity to glare, make the world look fuzzier at age 80 or 85. So, as these images show, everything from finding a bottle of pills in the medicine cabinet to reading the print in books such as this text can be a difficult task.

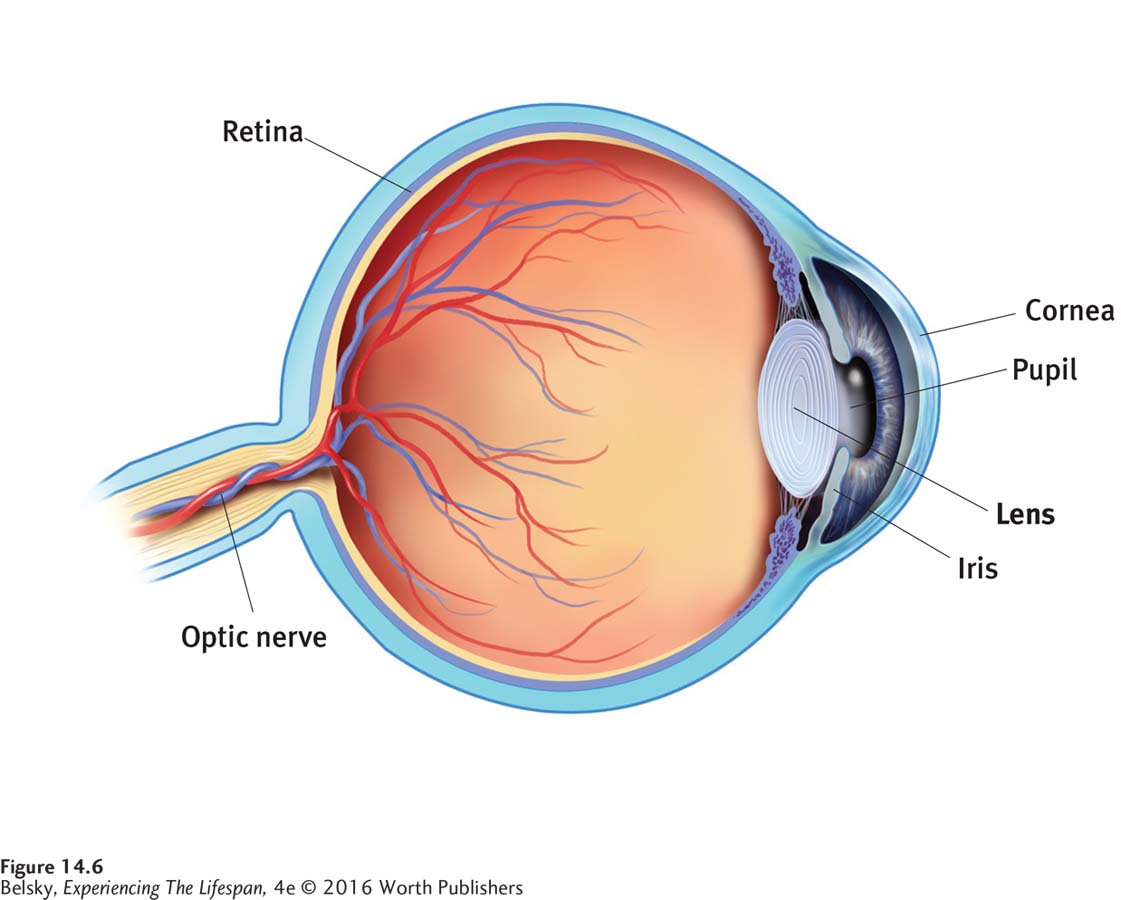

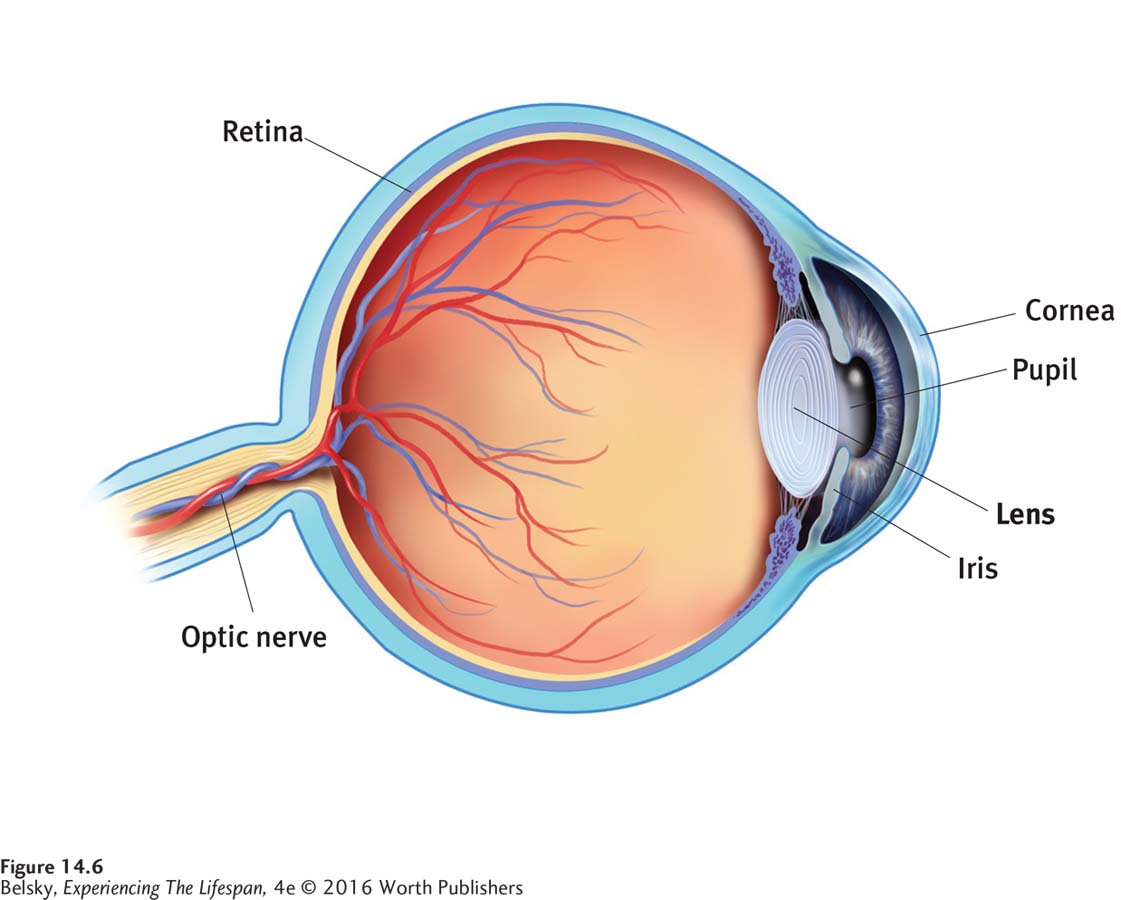

These signs of normal aging—presbyopia, problems seeing in the dark, and increased sensitivity to glare—are mainly caused by changes in a structure toward the front of the eye called the lens (see Figure 14.6). The disk-shaped lens allows us to see close objects by curving outward. As people reach midlife, the transparent lens thickens and develops impurities, and can no longer bend. This clouding and thickening not only produces presbyopia, but also limits vision in dimly lit places where people need as much light as possible to see.

Figure 14.6: The human eye: Deterioration in many structures of the eye contributes to making older adults’ vision poor. However, changes in the lens, shown here, are responsible for presbyopia and also contribute greatly to impaired dark vision and sensitivity to glare—the classic signs of “aging vision.”

These changes also make older adults more sensitive to glare. Notice how, when sunlight hits a dirty window, the rays scatter and it becomes impossible for you to see out. Because they are looking at the world through a cloudier lens, older people see far less well when a beam of light shines in their eye. When this normal, age-related lens clouding becomes so pronounced that the person’s vision is seriously impaired, the outcome is that familiar late-life chronic condition—a cataract.

The good news is that cataracts are curable. The physician simply removes the defective lens and inserts a contact lens. The bad news is that the other three top-ranking old-age vision conditions—macular degeneration (deterioration of the receptors promoting central vision), glaucoma (a buildup of pressure that can damage the visual receptors), and diabetic retinopathy (a leakage from the blood vessels of the retina into the body of the eye)—can sometimes permanently impair sight.

INTERVENTIONS: Clarifying Sight

To lessen the impact of the normal vision losses basic to getting old, again, the key is to modify the wider world. People should make sure their homes are well lit, but avoid overhead light fixtures, especially fluorescent bulbs shining down directly on a bare floor, as these produce glare. They should design appliances with nonreflective materials and adjustable lighting. Putting enlarged letters and numbers on appliances will make the stove and computer keyboard easier to use.

Vision problems are a prime cause of ADL impairments because they make everything from working to walking a challenging task (Wahl and others, 2013). Poor vision is a risk factor for falling which, as you will see later, is a frightening event in later life (Ambrose, Paul, & Hausdorff, 2013; Kallstrand-Erikson and others, 2013).

This brings up the social consequences of seriously limited sight: not leaving the house because you are afraid of falling; suffering the pain of depending on loved ones for jobs you used to do: “I feel so embarrassed . . . ,” said one man; “. . . I can’t even change a fuse, and it’s embarrassing, belittling” (quoted in Girdler, Packer, & Boldy, 2008, p. 113). People might experience the uncomfortable feeling of being “overprotected” (meaning infantilized) by well-meaning friends and family.

These fears are well founded. When researchers polled older adults attending a low-vision clinic, over time, more respondents agreed with comments such as, “People don’t let me do what I could do for myself” (Cimarolli and others, 2013).

Given this danger, how can loved ones help? Encourage the person to visit a low vision center for rehabilitation, because these programs work (Smallfield, Clem, & Myers, 2013). Consider Jim Vlock, a retired executive whose eyes were literally opened when he (reluctantly) visited a center for the visually impaired. After an evaluation, Mr. Vlock emerged laden with devices, from a talking watch, to specialized glasses for different tasks, to a computer with an enlarged screen that can “read for him.” As one center director put it, “Too often we get patients who . . . have lost their jobs, their wives, their home. . . . Our philosophy is to get patients to do things for themselves so they can feel fulfilled.” (See Brody, 2010.)

Actually people with vision impairments adopt different creative coping techniques on their own (Schilling and others, 2013)—from rearranging the wider world (“I make contrasts everywhere”; “I just bought new white mugs so I can see where the coffee is,” said one woman), to drawing on their positivity skills to see life with new eyes (“Let me take pleasure in the many things I still can do”). These encouraging findings explain why even serious vision disorders are not linked to depression in old age (Kiely, Anstey, & Luszcz, 2013). This is not true of that other important sense—hearing.

Our Bridge to Others: Hearing

It’s natural to worry most about losing our sight in old age. But one study showed hearing impairments are more prone to produce depression than almost any other medical problem of later life (Mener and others, 2013). The reason is that hearing loss can provoke loneliness (Kiely, Anstey, & Luszcz, 2013: Pronk, Deeg, & Kramer, 2013) because it robs us from understanding language, our bridge to other minds. Poor hearing isolates us from the human world.

Unfortunately, late-life hearing problems are common. They affect 1 in 3 people in their sixties. By the next decade, the statistics double, to almost 2 out of 3 (Bainbridge & Wallhagen, 2014). The figures are particularly alarming for men. Around the world, males are several times more likely than women to develop hearing losses in midlife (Belsky, 1999).

One reason is that age-related hearing loss has an environmental cause: exposure to noise. Men are more likely to be construction workers, ride motorcycles, and go to NASCAR races. These high-noise environments can provoke hearing handicaps at an unusually young age. Government regulations mandate hearing protection devices for workers in noisy occupations, which may partly explain why in recent decades, U.S. hearing loss rates have stabilized or declined (Bainbridge & Wallhagen, 2014). Still, from exposing ourselves to the roar of rock concerts to embedding an iPod in our ear, these statistics are apt to stay stubbornly high as today’s emerging adults travel into their older years.

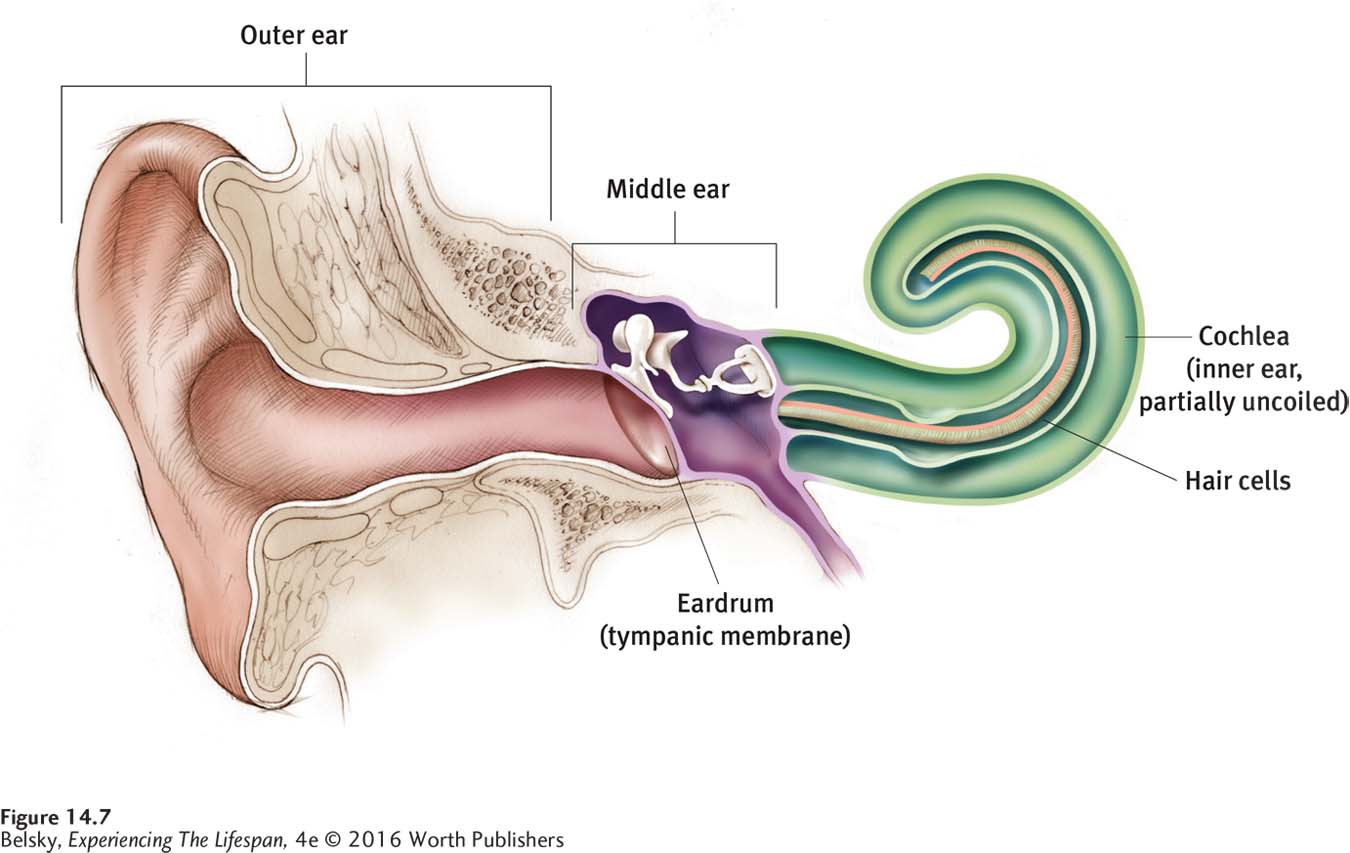

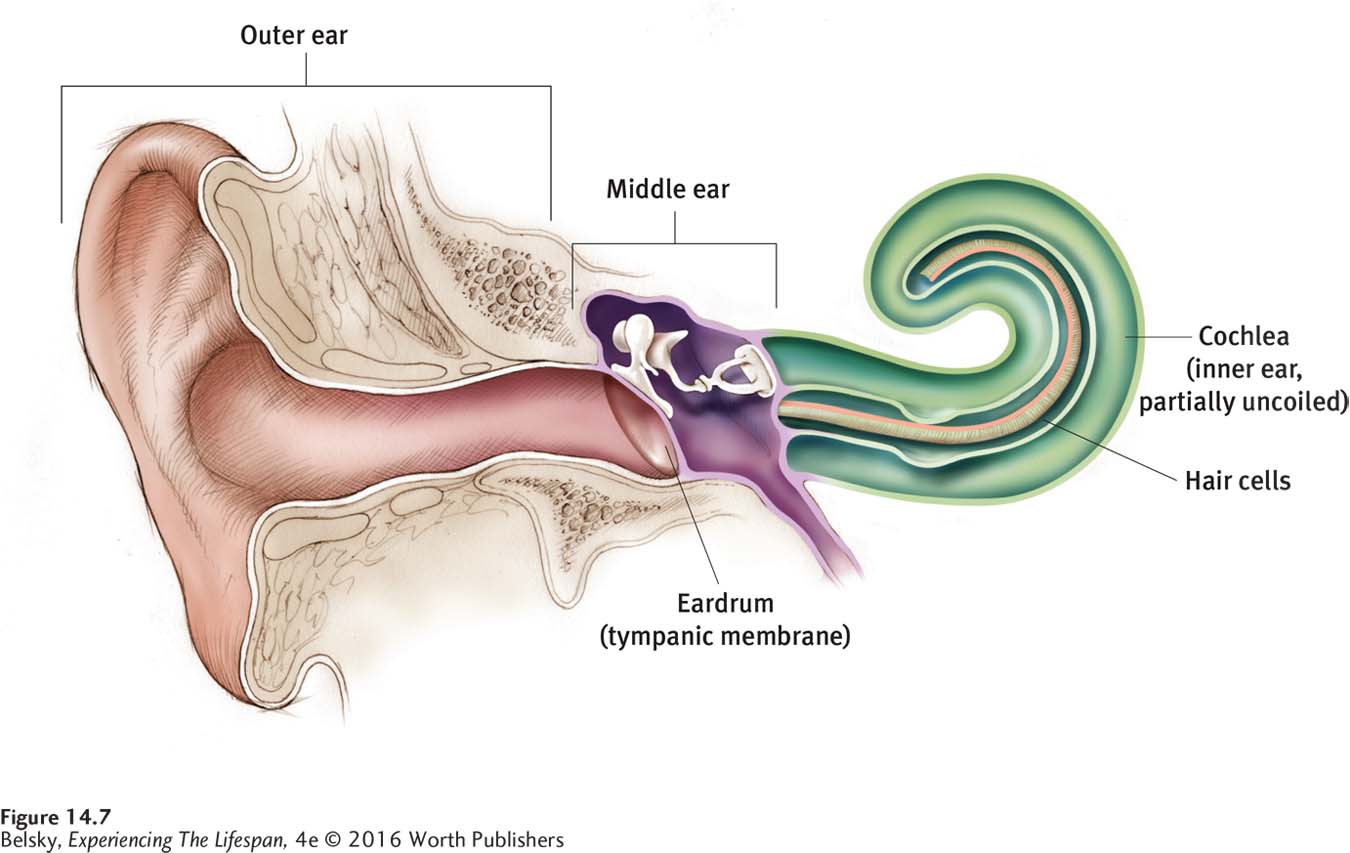

Presbycusis—the characteristic age-related hearing loss—is caused by the atrophy or loss of the hearing receptors, located in the inner ear (Yamasoba and others, 2013; see Figure 14.7). This irreversible change, compounded by the neural declines discussed in the previous chapter, affect people’s ability to quickly process speech as early as midlife (Clinard & Tremblay, 2013). The receptors coding high-pitched tones are most vulnerable. So, older people have special difficulties hearing consonants, for instance mistaking the word time for dime, because these sounds are delivered at a higher pitch (Bainbridge & Wallhagen, 2014).

Figure 14.7: The human ear: Presbycusis is caused by the selective loss of the hearing receptors in the inner ear—called hair cells—that allow us to hear high-pitched tones—so these changes are permanent.

Put yourself in the place of someone with presbycusis. Because of your speech decoding difficulties, listening to conversations feels like hearing a radio filled with static. (That’s why older people complain: “I can hear you, but I can’t understand you.”) Because your impairment has been progressing gradually, you may not be sure you have a problem, thinking, “Other people talk too softly.” If you are like most hearing-impaired people, you won’t get a hearing aid (Laplante-Levesque, Hickson, & Worrall, 2010). Hearing aids are expensive and a hassle to manage, or so you have heard (see McCormack & Fortnum, 2013). After all, you can hear fairly well in quiet situations. It’s only when it gets noisy that you can’t hear at all.

Being in a wheelchair seriously compromises anyone’s quality of life. But this woman’s hearing impairment, which makes having a conversation with her husband practically impossible, may be even more important in cutting her off from the outside world. Moreover, if she is like most of older people, she won’t be using a hearing aid.

Copyright © Lon C. Diehl/PhotoEdit – All rights reserved.

Think of the pitch of the background noises surrounding you now: the hum of a computer, the sound of a car motor starting up. These sounds are lower in pitch than speech. This explains why hearing-impaired people complain about “all that noise.” Background sounds overpower the higher-pitched conversations they need to understand.

Imagine having a conversation with a relative who cannot hear well—having to repeat your sentences, needing to shout to make yourself understood. Although you love your grandpa dearly, you automatically cringe when he enters the room. Now, imagine that you are a hearing-impaired person who must continually say, “Please repeat that,” and you will understand why this ailment can provoke isolation. Hearing losses impair our ability to lovingly connect.

INTERVENTIONS: Amplifying Hearing

Because background noise is important in determining how well older people hear, one solution is to choose your social settings with care. Don’t go to a noisy restaurant. Avoid places with low ceilings or bare floors, as they magnify sound. Install wall-to-wall carpeting in the house to help absorb background noise. Get rid of noisy appliances, such as a rattling air conditioner or fan. If a loved one is receptive, you might mention that assistive devices such as flashing phones might improve his life.

Even though this aged woman may have spent her life as a Shakespeare scholar or a well-known scientist, her emerging-adult granddaughter will be tempted to talk to her frail, tiny grandma in elderspeak. How often have you used this patronizing type of speech with a cognitively sharp person in her eighties or nineties just because she looked as if she might be impaired?

© Ole Graf/Corbis

When talking to a hearing-impaired older adult, speak clearly and slowly. Face the person. Perhaps use gestures so the person can take advantage of multiple sensory cues (Diederich, Colonius, & Schomburg, 2008). But avoid elderspeak, the tendency to talk more in exaggerated tones (“HOW ARE YOU, DARLING? WHAT IS FOR DINNER TODAY?”).

Elderspeak—a mode of communication we tend to naturally fall into when an older person looks physically (and so mentally) impaired—has unfortunate similarities to infant-directed speech. We use simpler phrases and grammar, and employ infantile “loving” words, such as darling, that we would never adopt when formally addressing a “real” adult (Kemper & Mitzner, 2001). I’ll never forget going out to dinner with a friend in his late eighties who needed to use a walker, and cringing at how the 18-year-old server treated this intellectual man like a 2-year-old!

For your own future hearing, the message rings out loud and clear. Avoid high-noise environments and cover your ears when you pass by noisy places. Why do we hear so much about the need to exercise, and yet there is a deafening silence about protecting our hearing? How many of you religiously work out to prevent health problems like heart attacks but attend rock concerts without a thought? Think of the noise level at your fitness center. Could the same place where you are going to improve your health be producing this common age-related disease?

Ironically, the same noisy places that contribute to hearing losses now sometimes offer solutions for the hearing impaired. An assistive device is available in big city public venues—such as train, bus, and subway stations—that “delivers” loudspeaker announcements directly to a user’s hearing aid. This microphone-attached advance, called the hearing loop, makes speech crystal clear by bypassing the cacophony of background noise. (See Hearing Loop, n.d.). The hearing loop has now migrated to some community theaters and concert halls, and speaker-to-listener microphones show promise at amplifying personal conversations, too (see Aberdeen & Fereiro, 2014).

Still no external hookup can supplant that simple device, the hearing aid. So what causes the (beautifully named) “file drawer problem,” the fact that even after being fitted for a hearing aid, older people, not infrequently, give this device up?

Users complain that hearing aids (being so small) are cumbersome to adjust (McCormack & Fortnum, 2013). They are difficult to care for (Kelly and others, 2013). Worse yet, because they don’t completely compensate for the selective losses I’ve described, they don’t make your hearing perfectly normal . . . which bothers me, because I’m developing the hearing troubles discussed in this section as we speak. So if any budding mechanical genius is listening: You’ll benefit humankind, make billions, and most important, help your author, by inventing a perfect hearing aid!

The huge domed ceilings are awe-inspiring, but combined with bare floors and the clatter of commuters, they make New York City’s Grand Central Station an acoustic nightmare. However, thanks to the miracle of the hearing loop, people can now bypass that background noise via loudspeaker train announcements beamed directly to their hearing aids.

© Stuart Monk/Alamy

Motor Performances

Poor hearing causes heartaches when we communicate with older people one-to-one. What bothers us when we imagine the general category “old person” lies in the motor realm. The elderly are so slow!

Slowness puts older people out of sync with the physical world. It can make driving or getting across the street a challenging feat. It causes missteps in relationships, too. If you find yourself behind an elderly person at the supermarket checkout counter or an older driver going 40 in a 65-mile-per-hour zone, notice that your reaction is to get annoyed. So, age-related slowing alone may help explain why our fast-paced, time-oriented society has such negative prejudices against the old.

The slowness that is emblematic of old age is mainly caused by the loss in information-processing speed that starts decades earlier, in young adulthood (again described in Chapters 12 and 13). This slowed reaction time—or decline in the ability to respond quickly to sensory input—affects every action, from accelerating when the traffic light turns green, to hearing fast paced conversations, to performing well on a fluid IQ test.

This British road sign perfectly symbolizes our image of “the old”: ADL-impaired; needing special care; most of all, impossibly slow.

© Ball Miwako/Alamy

Age changes in the skeletal structures propelling action compound the slowness: With osteoarthritis, the joint cartilage wears away, making everything from opening a jar to running for the bus an endurance test. With osteoporosis, the bones become porous, brittle, and fragile, and break easily. Although men can also develop osteoporosis, women, as is well known, are more susceptible to this disease. The main reason is that females—particularly slender women—have frailer, smaller bones. With this illness, the fragile bones break at the slightest pressure and cannot knit themselves back together. Hip fractures are a special danger. They are a primary reason for needing to enter a nursing home (Jette and others, 1998).

Actually, as roughly 1 in every 3 older people falls in any given year, hip fractures are not infrequent in old age. The cost of fall-related injuries in hospitalizations and nursing home placement is enough to knock society off its feet—representing at least 0.1 percent of health-care expenditures in the United States and the European Union (Ambrose, Paul, & Hausdorff, 2013).

INTERVENTIONS: Managing Motor Problems

As the number one risk factor for falling is dizziness (see Olsson Möller and others, 2013), physicians should be careful about over-prescribing medications to older adults. Because gait and balance difficulties make falls more likely, people need to check out exercise programs focused on improving these skills (such as Tai Chi) (Gschwind, Bridenbaugh, & Kressig, 2010). Physical exercise can even somewhat reverse balance, strength, and mobility declines that are moderately severe (Ip and others, 2013).

Older people and their loved ones might also take steps to avoid tripping by using high-quality indirect lighting (as I mentioned earlier) and low-pile, wall-to-wall carpeting in their homes. Put grab bars in places such as in the bathtub, where falls are likely to occur. Install cabinet doors that open to the touch, and place shelves within easy reach. If a relative is worried about living independently, urge her to check out body sensors that signal health care providers if she trips and falls.

Medical scooters provide vital wheels to elderly and disabled adults—keeping this man physically connected to life.

© Peter Hvizdak/The Image Works

Actually, “lower body” impairments—because they limit mobility—are the number-one barrier to living independently in later life (Pressler & Ferraro, 2010). Suppose you needed help standing, and getting to the toilet was a scary balancing act? Still I know a man who cannot walk—and should be in a nursing home—whose life was transformed by that simple assistive device: the medical scooter. The scooter has permitted him to stay in his own home (with a lot of loving family support) and given him wheels to travel. It has also saved our government thousands of dollars in institutional care!

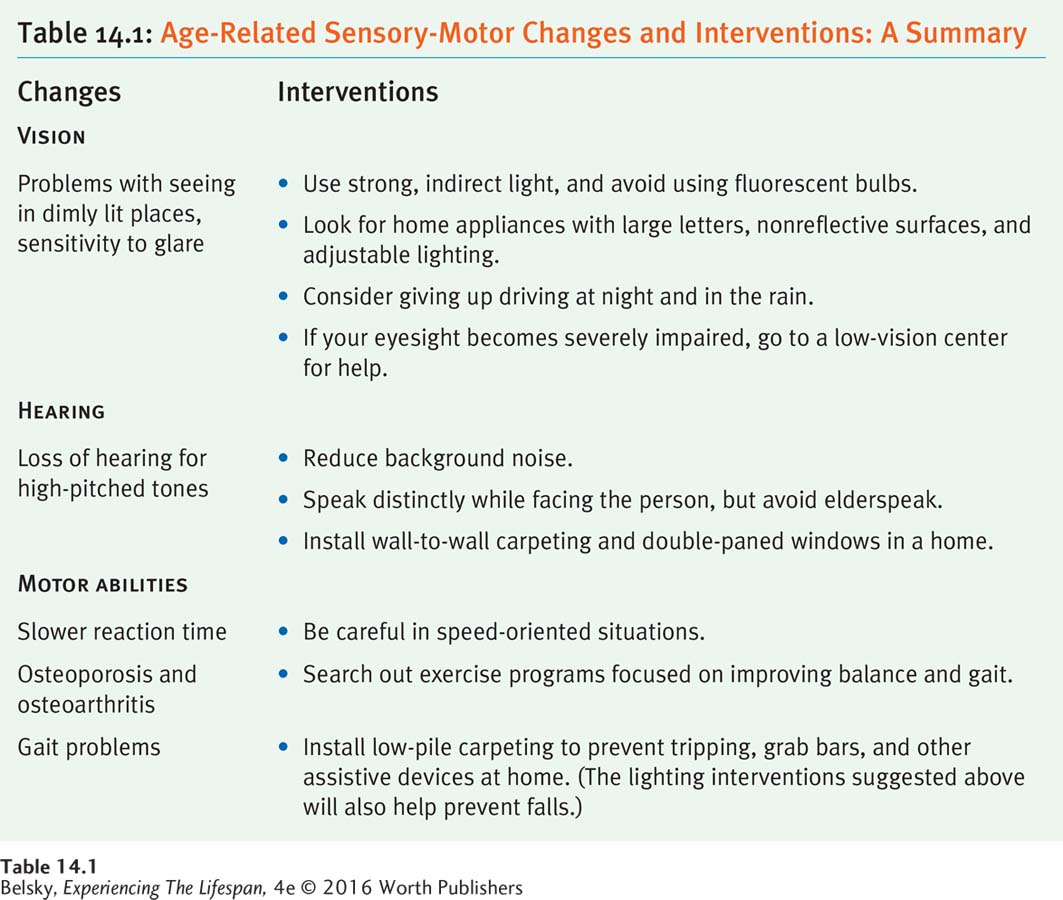

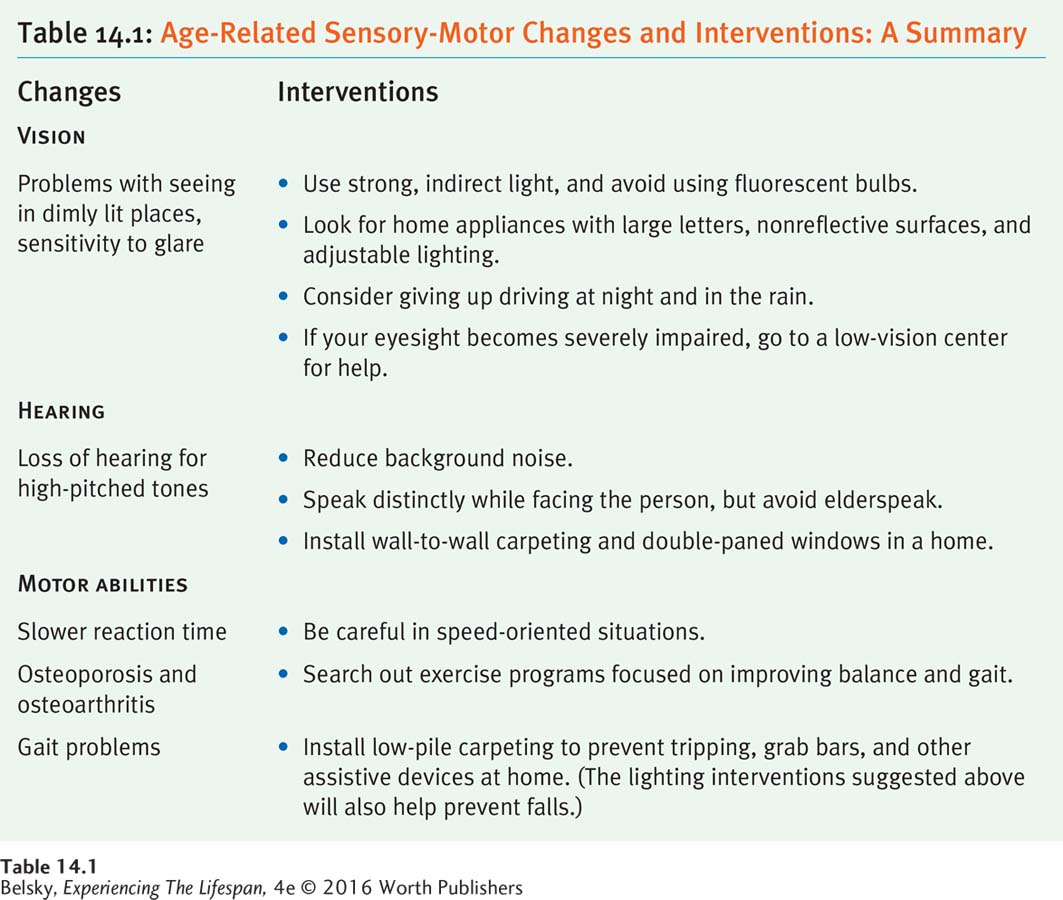

Table 14.1 summarizes the main points of this sensory-motor section, with special emphasis on highlighting what older adults and their loved ones can do to produce the right person–environment fit at home. How do the elderly handle that environmental challenge so important to staying independent: driving?

Hot in Developmental Science: Driving in Old Age

Imagine that you are an elderly person whose vision problems or lower-body impairments are making driving dangerous. You first stop driving during rush hour. For years, you have been uncomfortable driving at night and in the rain. But even though you are aware of having problems, if you are like many older people, you cannot imagine giving up your car (Lindstrom-Forneri, Tuokko, & Rhodes, 2007). Abandoning driving means confronting the loss of independent selfhood that you first gained when you got your license as a teen. Giving up driving might even force you to abandon your home and enter a nursing home.

Actually, driving is a special concern for the elderly because it involves many sensory and motor skills. In addition to demanding adequate vision, driving is affected by hearing losses because we become alert to the location of other cars partly by their sound (see Munro and others, 2010). To drive well demands having the muscle strength to push down the pedals and the joint flexibility to turn the wheel. And, as anyone behind an older driver when the light turns green knows, driving is especially sensitive to slowed reaction time.

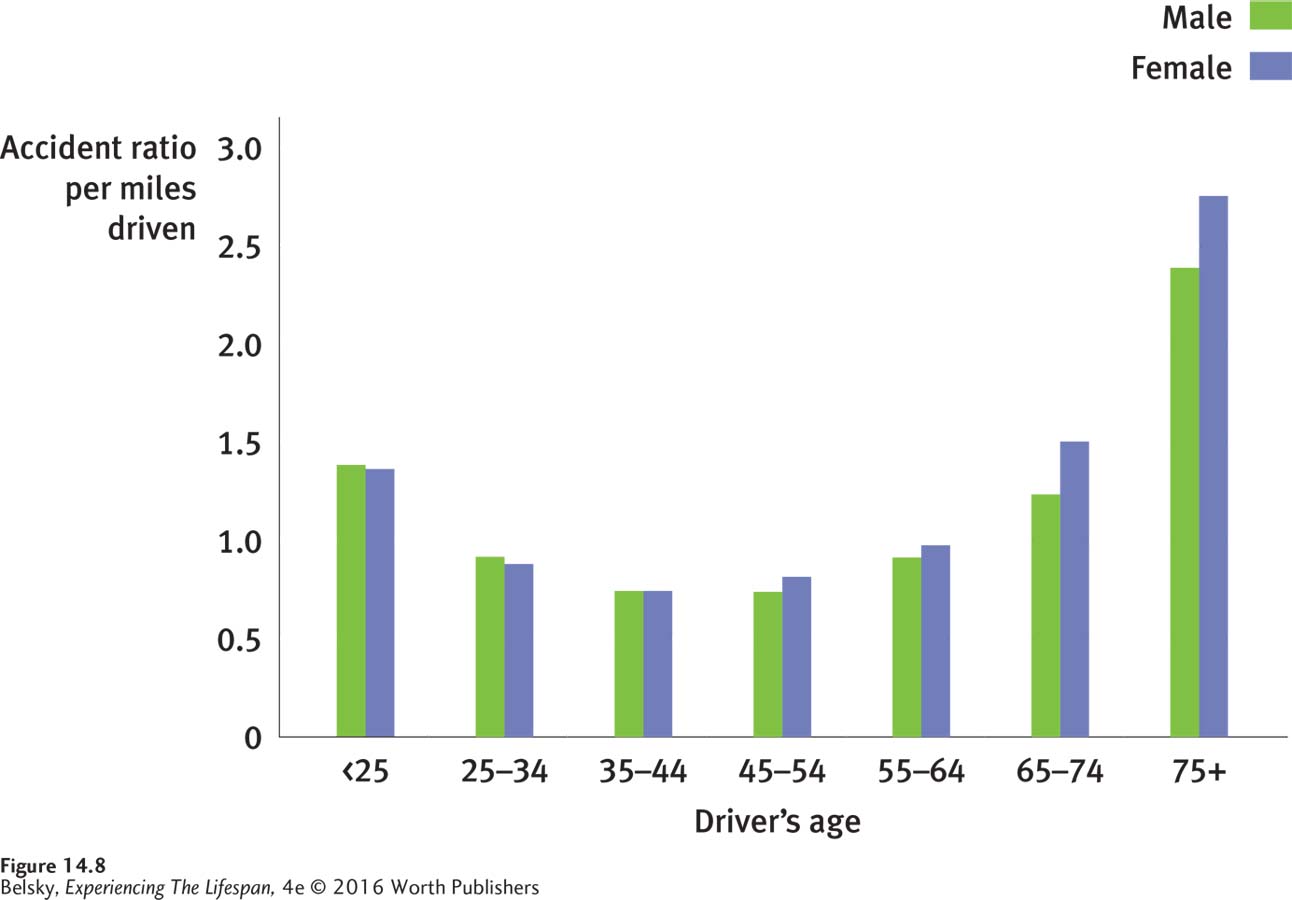

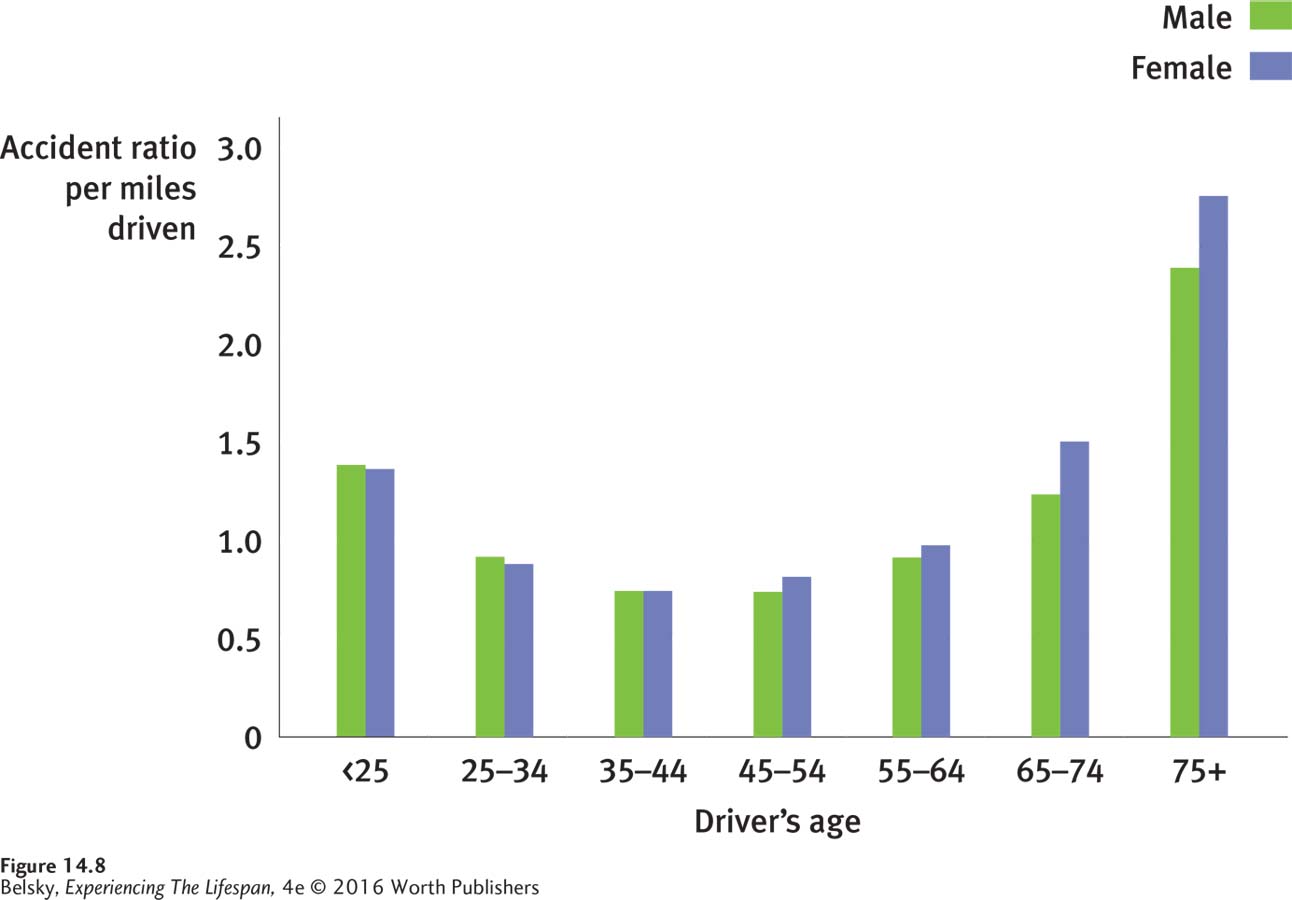

The good news is that older people—more often women than men (Sarkin and others, 2013; Tuokko and others, 2013)—limit their driving, especially when they reach the old-old years (Tuokko and others, 2013). Elderly drivers, one video study showed, pay special attention to the road when they are in heavy traffic and make left or right turns (Charlton and others, 2013). The bad news is that a small percent of drivers (roughly 1 in 10 older people in one study) rank their skills as excellent, even when on-road assessments by examiners show they are unsafe to drive (Wood, Lacherez, & Anstey, 2013). This may explain why accident rates shoot upward during the old-old years (Stamatiadis, 1996; see also Ross and others, 2009; see Figure 14.8).

Figure 14.8: Accident rates in U.S. urban areas, by age and gender: Driving is especially dangerous for drivers age 75 and over. Notice that, if we look at per person miles driven, old-old drivers have accident rates that outpace those in the other highest-risk group—teenagers and emerging adults.

Data from: Stamatiadis, 1996.

Imagine you are a passenger and your 90-year-old uncle is behind the wheel. When should you be most concerned? Expect special trouble at complex intersections—which demand divided attention and complex information processing. For similar reasons, expect making difficult left turns into traffic to be unusually hair-raising (Clarke and others, 2010). Obviously, the danger accelerates in poor visibility with traffic around (Trick, Toxopeus, & Wilson, 2010).

Vision problems, hearing difficulties, and especially slowed reaction time—all combine to make this 80-year-old a more dangerous driver. Moreover, he will have special trouble driving in high risk situations.

Jose Luis Pelaez, Inc./Getty Images/Blend Images

What should society do? Our first thought would be to require yearly license renewals, accompanied by vision tests for people over 75. Still, a simple eye test will not be enough. With late-life driving difficulties, reaction-time issues loom large (Martin and others, 2010). Because the elderly have trouble processing the changing array of stimuli on the road (Roenker and others, 2003), to really weed out dangerous drivers, we might need to give each older driver neuropsychological tests (Dawson and others, 2010). Should we rely on relatives or ask physicians to report impaired older drivers? Would you have the courage to rob your uncle of his adult status by taking away his keys?

None of these interventions speaks to the larger issue: “If I can’t drive, I may have to leave my home.” We need to redesign the driving environment by putting adequate lighting on road signs, streets, highways, and, especially, exit ramps. We need to construct walkable communities, invest in mass transportation, and take other steps to liberate people from cars. This mandate is mandatory to tackle our global energy problems, ballooning obesity, and the looming ADL crisis as the baby boomers move down the highway of later life.

On your way home tonight, think of how to change the driving environment to provide a better person–environment fit for older adults (and yourself!). This environmental engineering is crucial when dealing with the most feared condition of old age: major neurocognitive disorders, or dementia.

Tying It All Together

Question

14.5

Roy, who is 55, is having trouble seeing in the dark and in glare-filled environments. Roy’s problem is caused by the clouding of his cornea/iris/lens. At age 80, when Roy’s condition has progressed to the point where he can’t see much at all, he will have a cataract/diabetic retinopathy/macular degeneration, a condition that can/cannot be cured by surgery.

lens; cataract; can

Question

14.6

Dr. Jones has just given a 45-year-old a diagnosis of presbycusis. All of the following predictions about this patient are accurate except (pick out the false statement):

The patient is likely to be a male.

The patient has probably been exposed to high levels of noise.

The patient is at risk for becoming isolated and depressed.

The patient will hear best in noisy environments.

d

Question

14.7

Your 75-year-old grandmother asks for advice about how to remodel her home to make it safer. Which modifications should you suggest?

Install low-pile carpeting and put grab bars in the bathroom.

Put fluorescent lights in the ceilings.

Buy appliances with larger numerals and nonreflective surfaces.

Put a skylight in the bathroom that allows direct sunlight to shine down on the medicine cabinet.

Get rid of noisy air conditioners and fans.

a, c, and e. (Suggestions b and d will make grandma’s eyesight worse.)

Question

14.8

Your state legislature is considering a law to require annual eye exams for drivers over the age of 75. Explain to the lawmakers why this law may not be effective, and offer some alternate strategies that could minimize the dangers of needing to drive in old age.

Tell the lawmakers that relying just on an eye exam won’t be effective because driving is dependent on many sensory and motor skills. Suggest sponsoring bills to change roads by putting adequate lighting on exit ramps, more traffic signals at intersections (especially left-turn signals), and exploring other ways to make the driving environment more age-friendly. Most important, foster initiatives that don’t depend on driving: Invest in public transportation. Give tax incentives to developers to embed shopping in residential neighborhoods, and encourage creative alternatives to cars.