14.3 Neurocognitive Disorders (NCDs)

Major neurocognitive disorder (commonly known as dementia) is the general label for any illness that produces serious, progressive, and often irreversible cognitive problems that compromise a person’s ability to function. (The framers of the current U.S. diagnostic manual, DSM-

The devastating mental losses produce the total erosion of our personhood, the complete unraveling of the inner self. Younger people can also develop a neurocognitive disorder if they have a brain injury or an illness such as AIDS. However—

433

What is the cognitive decline really like? As you can poignantly see in the Experiencing the Lifespan box, in the earlier stages, people forget basic semantic information. They cannot recall core facts about their lives, such as the name of their town or how to get home. Impairments in executive functions are prominent. A conscientious person behaves erratically. An extrovert withdraws from the world.

Experiencing the Lifespan: An Insider Describes His Unraveling Mind

Hal is handsome and elegant, a young-

I first noticed that I had a problem giving short speeches. You have a blank and like . . . what do I put in there. . . . I can speak. You are listening to me and you don’t hear any pauses, but if you get me into something. . . . I just had one of these little pauses. I knew what I wanted to say and I couldn’t get into it, so I think a little bit and wait and try to get around to it. I know it’s there . . . but where do I use it? . . . It’s ups and downs; and then one day you are in a deep valley. You can’t get tied up in the hills and valleys because they just lead you around and it makes you more frustrated than ever. . . . If I can’t get things, I just give up and then try to calm down and come back to it. Like, when I read, I get confused; but then I just stop and try again a month later. Or the people here: I know them by face, by sight, but I cannot get that focus down to memorize any names. I remember things from when I was five. It’s what’s happening now that doesn’t make a lot of sense.

As we walk to my car after this interview, Hal’s daughter fills me in:

My father seems a lot happier now that he is here. The problem is the frustration, when he tries to explain things and I can’t understand and neither of us connects. Then he gets angry, and I get angry. My father has always been a very intellectual person, so feeling out of control is overwhelming for him. . . . He has days where he gets paranoid, decides that there is a conspiracy out for him. It’s tiny things. A letter came to the wrong place and he went down and exploded at the people at the desk. For me the worst thing is remembering how my father was. You expect a certain response from him and you get this strange response. It’s like there’s a different person inside.

As the symptoms progress, every aspect of thinking is affected. Abstract reasoning becomes difficult. People can no longer think through options when making decisions. Their language abilities are compromised. People cannot name common objects, such as a shoe or a bed. Judgment is gone. Older adults may act inappropriately—

When these diseases reach their later stages, people may be unable to speak or move. Ultimately, they are bedridden, unable to remember how to eat or even swallow. At this point, complications such as infections or pneumonia often lead to death.

The Dimensions of These Disorders

How long does this devastating decline path take? As you will see later, there is an in-

434

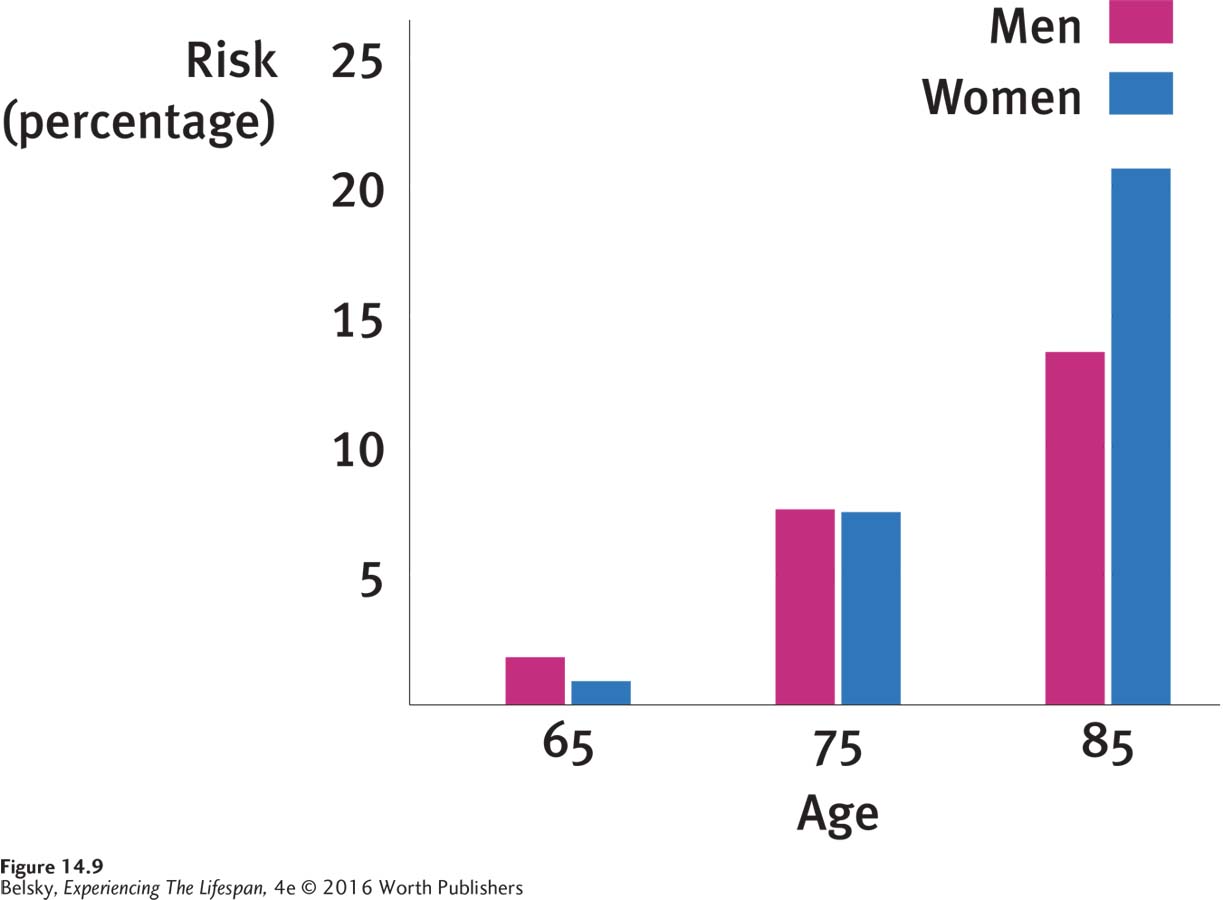

The good news is that these devastating mental impairments are typically illnesses of advanced old age. Among the young-

Neurocognitive Disorders’ Two Main Causes

What conditions produce these terrible symptoms? Although there is a host of rarer late life diseases, typically the older person will be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia or some combination of those two illnesses.

Vascular neurocognitive disorder (also called vascular dementia) involves impairments in the vascular (blood) system, or network of arteries feeding the brain. Here, the person’s cognitive problems are caused by multiple small strokes.

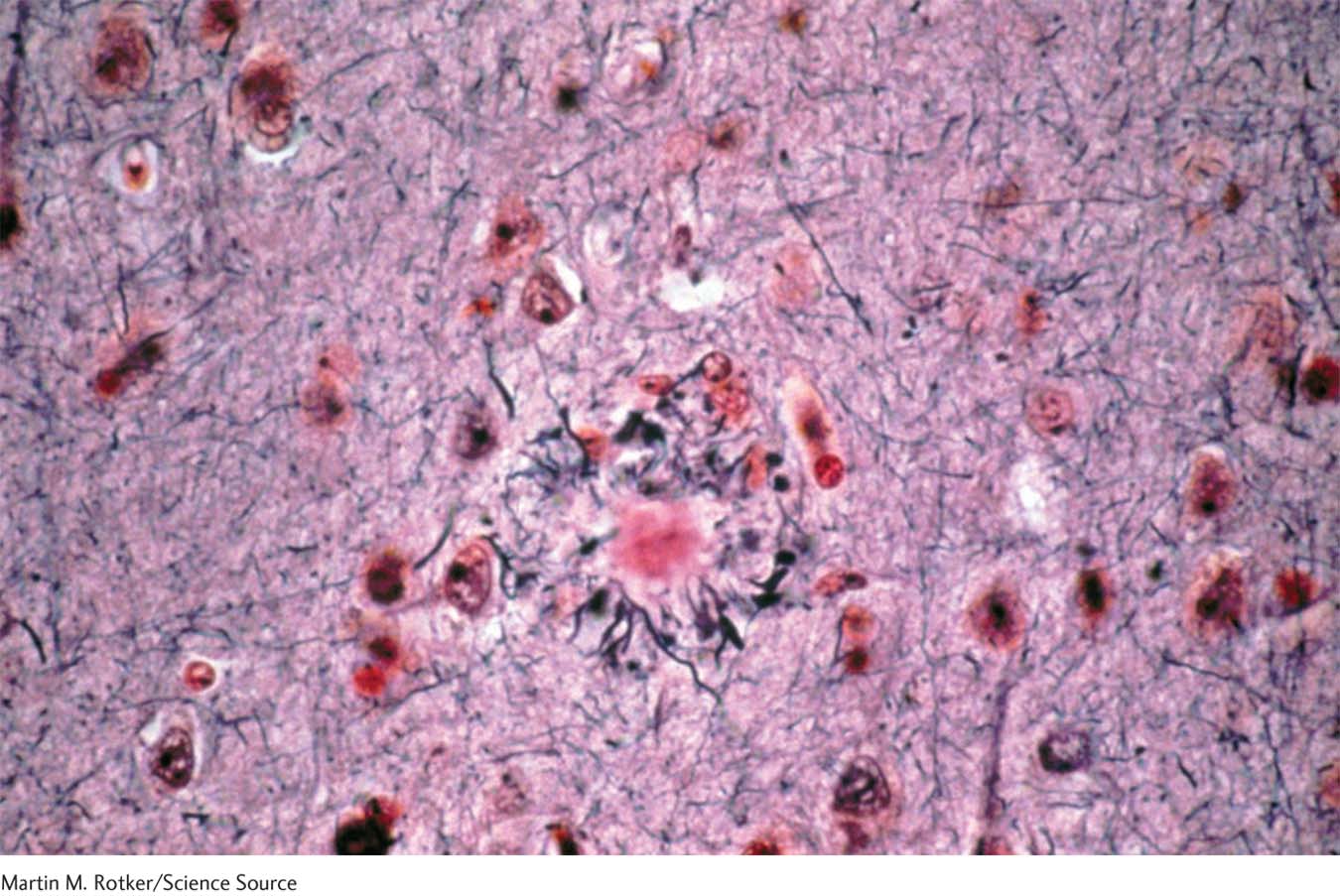

Neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease (typically called Alzheimer’s disease) directly attacks the core structure of human consciousness, our neurons. With this illness, the neurons wither away and are replaced by strange wavy structures, called neurofibrillary tangles, and, as you can see in this photo, thick, bullet-

Vascular problems—

As you just saw, the number-

This breakthrough in the genetics of Alzheimer’s poses a dilemma. Children who have witnessed a parent develop this illness are (no surprise) terrified of the disease. Knowing they don’t have the genetic marker would ease their minds. But having the APOE-

Targeting the Beginnings: The Quest to Nip Alzheimer’s in the Bud

The main front in the war to prevent Alzheimer’s centers on a protein called amyloid, a fatty substance that is the basic constituent of the senile plaques. According to much—

435

This means early diagnosis is crucial. But since scientists cannot look into the brain to see the individual neurons, as of this writing there is no definitive medical test showing the person is getting ill. The current way of diagnosing Alzheimer’s is to: (1) Look for a history of steady mental deterioration (rapid mental confusion signals a state called delirium which, in the elderly, may be due to anything from medication side effects to a heart attack); (2) rule out other physical and psychological causes; and (3) explore the person’s performance on neuropsychological tests.

Older adults diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment are centrally important in this research goal. These people show serious learning impairments but have yet to cross the line to Alzheimer’s disease. Not everyone with mild cognitive impairment makes the transition to Alzheimer’s. In fact some people—

The fact that the APOE-

In the meantime, is there anything you and I can do? Adopting a heart-

What clearly does improve cognitive function in middle-

INTERVENTIONS: Dealing with These Devastating Disorders

What about those Alzheimer’s drugs we see advertised on TV? Unfortunately, their effects, put charitably, are minor at best (Rabins, 2011). With this illness, the main interventions are environmental. They involve providing the best disease–

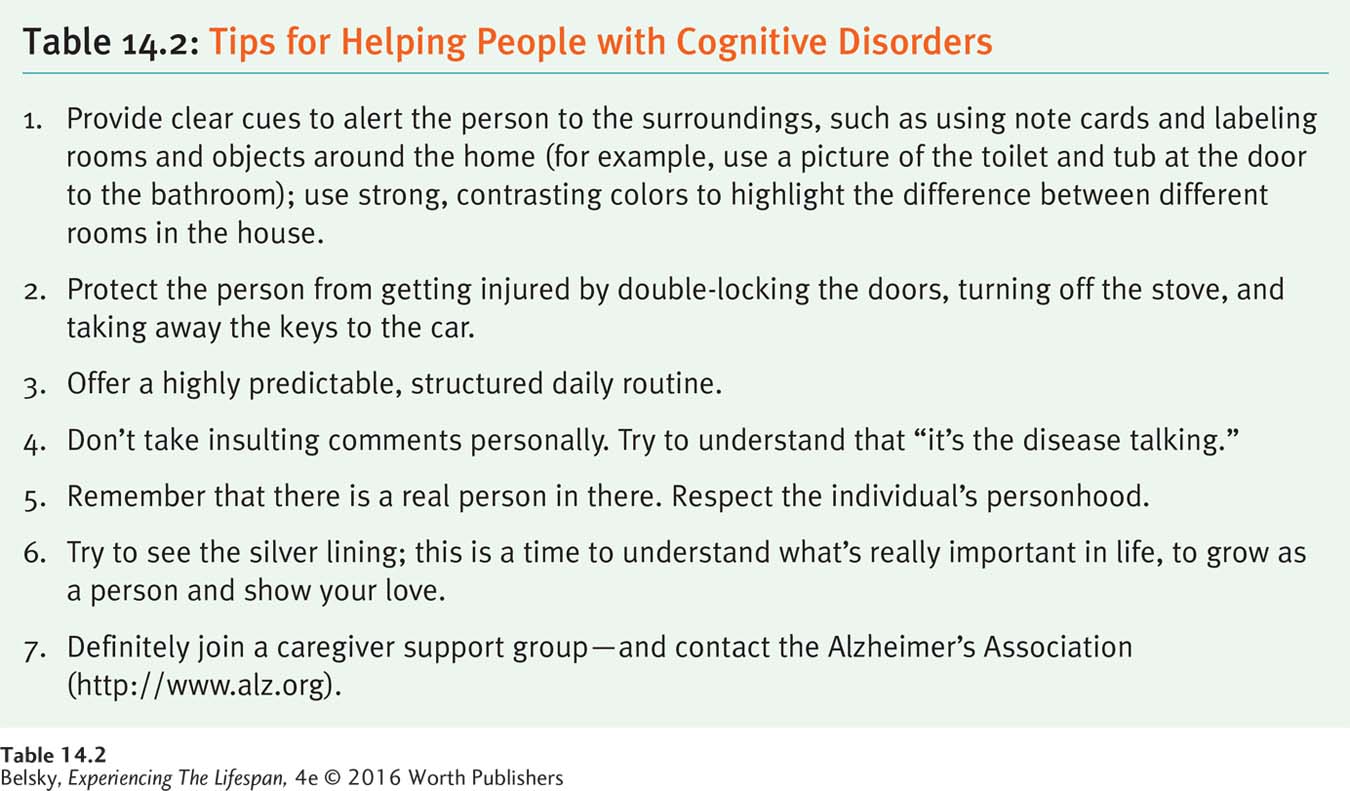

FOR THE PERSON: USING EXTERNAL AIDS AND MAKING LIFE PREDICTABLE AND SAFE. Creative external aids such as using note cards can jog memory when people are in the earlier stages of Alzheimer’s. It helps to put shoes right next to socks or the coffee pot by the cup, and verbally remind the person what to do. A prime concern is safety. To prevent people from wandering off (or driving off!), double-

436

So far, I have mainly discussed what others can do for these devastating impairments—

Well, the first word that comes to my mouth is fear; becoming an infant, incontinence, not knowing who you are . . . I can go on and on, with those kinds of expressions.

(quoted in MacRae, 2008, p. 400)

Outsiders can compound this terror when they develop their own memory problem—

The last person who interviewed me was the neurologist. He was very indifferent and said it was just going to get worse. . . . Health-

(quoted in Snyder, 1999, pp. 17–

Can people use their late-

Life is a challenge . . . I am alive and I’m going to live life to the best I can. (If) people want to (say) oh what’s the point in living? Well, they’ve stopped living. . . . you only get one chance and this is it. Make the most of it.

(quoted in MacRae, 2008, p. 401)

Another man named Gorman went even further:

This early diagnosis has given me time to enjoy the life I have now. . . .: A beautiful sunset, a tree in the spring, the rising sun. Yes, having Alzheimer’s has changed my life; it has made me appreciate life more. I no longer take things for granted.

(quoted in MacRae, 2008, p. 401)

Can older adults with Alzheimer’s give us other insights into what it means to be wise? Judge for yourself, as you read what a loving dad named Booker said about the cycle of life:

I’m blessed to have a wonderful daughter. I sent her to . . . school and college and now she takes care of all of my business. . . . I’m in her hands. I’m in my baby phase now, so to speak. So sometimes I call her “my mumma.” . . . Yes, she’s my mumma now. [Booker smiled appreciatively.] . . . She’s my backbone. She’s such a blessing to me.

(quoted in Snyder, 1999, p. 103)

FOR THE CAREGIVER: COPING WITH LIFE TURNED UPSIDE DOWN. Imagine your beloved father or spouse has Alzheimer’s or another irreversible cognitive disorder. You know that the illness is permanent. You helplessly witness your loved one deteriorate. As the disease progresses to its middle stage, you must deal with a human being who has turned alien, where the tools used in normal encounters no longer apply. The person may be physically and verbally abusive, wake and wander in the night. When the 24/7 symptoms produce total role overload (Infurna, Gerstorf, & Zarit, 2013), you face the guilt of putting your loved one in a nursing home (Graneheim, Johansson, & Lindgren, 2014). Or, you decide to put your own life on hold for years and care for the person every minute of the day.

437

What strategies do people use to cope? One study with African American caregivers revealed that people rely on their faith for solace: “This is my mission from God” (Dilworth-

Another key lies in relishing the precious moments together you have left:

(Tom and Jane, married for 63 years, who were being interviewed about the illness) sat close to one another on the couch . . . and shared a great deal of smiles and giggles … and at times it felt they were the only people in the room . . . Although the stories Jane told did not always make sense, her eyes lit up whenever a question was asked about her marriage to Tom . . . What cannot be easily captured on paper were the warm interactions . . . The investigators felt privileged to be part of such a rich process in which one couple had the opportunity to share the story of their relationship together.

(quoted in Daniels, Lamson, & Hodgson, 2007, p. 167)

Yes, dealing with a loved one with these disorders is embarrassing (Montoro-

Until this point, I’ve been exploring how older people and their loved ones can personally take action to promote the best person–

Tying It All Together

438

Question 14.9

Your grandmother has just been diagnosed with a major neurocognitive disorder. Describe the two disease processes that typically cause this condition.

The illnesses are neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease, involving the deterioration of the neurons and their replacement with senile plaques and tangles, and vascular neurocognitive disorder, which involves small strokes. (Grandma—

Question 14.10

Mary, age 50, is terrified of getting a neurocognitive disorder. Which statement can you make that is both accurate and comforting? (Pick one.) a. Don’t worry. These conditions are typically illnesses of the “old-

a

Question 14.11

You are giving a status report to a Senate Committee on biomedical efforts to prevent Alzheimer’s disease. First, target the main research problem scientists face. Then, offer a tip to the worried elderly senators about a strategy that might help ward off the illness.

The main problem scientists face is diagnosing cognitive problems before they progress to the disease stage—

Question 14.12

Mrs. Jones has just been diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s disease. Her relatives might help by:

taking steps to keep her safe in her home.

encouraging her to attend an Alzheimer’s patient support group.

treating her like a human being.

doing all of the above.

d