15.1 Setting the Context

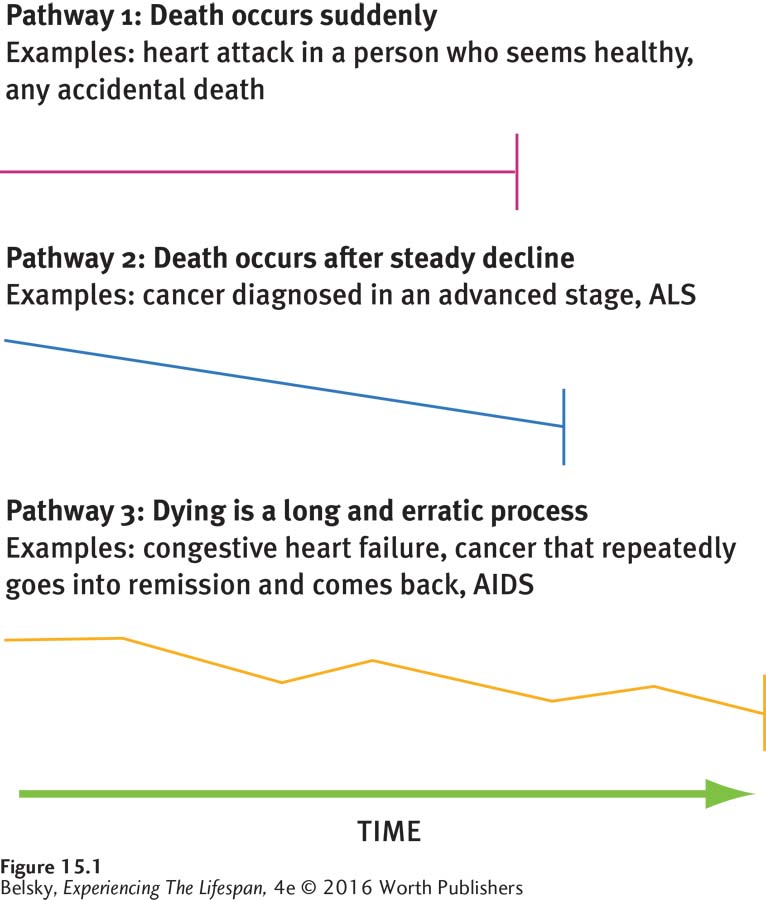

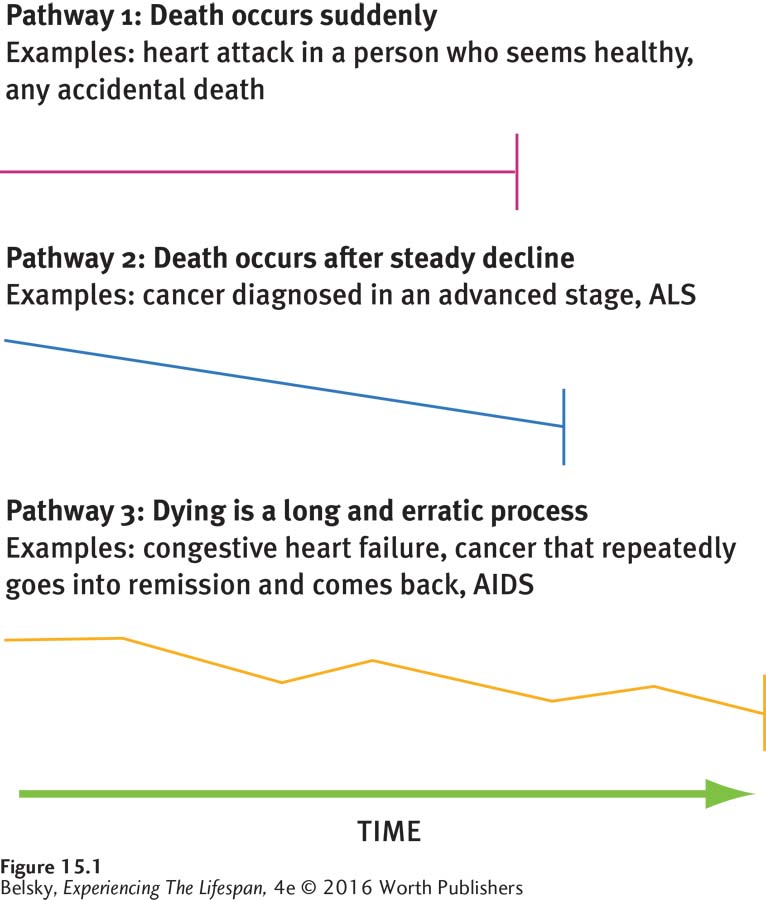

Today, as Figure 15.1 suggests, our pathways to death take different forms (Field, 2009). As happened most dramatically in the World Trade Center tragedy, roughly 1 out of every 6 or 7 people in developed nations dies without warning—as a result of an accident or, more often, of a sudden, fatal, age-related event, such as a heart attack or stroke (Enck, 2003; see the red line in Figure 15.1). My father’s death fit the pattern when illnesses such as cancer are discovered at an advanced stage. Here, as the blue line shows, a person is diagnosed with a fatal disease and steadily declines.

Figure 15.1: Three pathways to death: Although some people die suddenly, the pattern in blue and especially that in yellow are the most common pathways by which people die today.

The prolonged, erratic pattern, shown in yellow, is the most common dying pathway in our age of extended chronic disease. After developing cancer—or, like my husband, congestive heart failure (see the Experiencing the Lifespan Box, on page 455)—people battle that condition for years, helped by medical technology, until death occurs.

So today, deaths in affluent countries typically occur slowly. They are dominated by medical procedures. They have a protracted, uncertain course (Field, 2009; Harris and others, 2013). For most of human history, people died in a different way.