15.3 The Dying Person

How do people react when they are diagnosed with a fatal illness? What are their emotions as they struggle with this devastating news? The first person to scientifically study these topics was a young psychiatrist named Elisabeth Kübler-

Kübler-

While working as a consultant at a Chicago hospital during the 1960s, Kübler-

Kübler-

When a person first gets some terrible diagnosis, such as “You have advanced lung cancer,” her immediate reaction is denial. She thinks, “There must be a mistake,” and takes trips to doctor after doctor, searching for a new, more favorable set of tests. When these efforts fail, denial gives way to anger.

In the anger stage, the person lashes out, bemoaning her fate, railing at other people. One patient may get enraged at a physician: “He should have picked up my illness earlier on!” Others direct their fury at a friend or family member: “Why did I get lung cancer at 55, while my brother, who has smoked a pack of cigarettes a day since he was 20, remains in perfect health?”

Eventually, this emotion yields to a more calculating one: bargaining. Now, the person pleads for more time, promising to be good if she can put off death a bit. Kübler-

The day preceding the wedding she left the hospital as an elegant lady. Nobody would have believed her real condition. She . . . looked radiant. I wondered what her reaction would be when the time was up for which she had bargained. . . . I will never forget the moment she returned to the hospital. She looked tired and somewhat exhausted and before I could say hello, said, “Now don’t forget I have another son.”

(1969, p. 83)

453

Then, once reality sinks in, the person gets depressed and, ultimately, reaches acceptance. By this time, the individual is quite weak and no longer feels upset, angry, or depressed. She may even look forward to the end.

Kübler-

TERMINALLY ILL PEOPLE DO NOT ALWAYS WANT TO DISCUSS THEIR SITUATION. Although she never intended this message, many people read into Kübler-

The bottom line is that people who are dying behave just as when they are living (which they are!). They are leery about bringing up painful subjects. People don’t shed their sensitivity to others and feelings about what topics are appropriate to discuss when they have a terminal disease. Actually, as life is drawing to a close, preserving the quality of our attachment relationships is a paramount agenda—

NOT EVERY PERSON OR FAMILY FEELS IT’S BEST TO SPELL OUT “THE FULL TRUTH.” As you saw earlier with the Hmong, the idea that we must inform terminally ill patients about their condition is also not universally accepted. Yes, in our individualistic society, people say they are interested in knowing the facts: “Information is important,” said one Swedish woman with cancer. “Even if you have a short time left, you have to plan this time” (quoted in Saeteren, Lindström, & Nåden, 2010, p. 814). But they may not want doctors to get specific when the prognosis is dire (Baile, Aaron, & Parker, 2009; Innes & Payne, 2009). Families go further: “Don’t tell my loved one anything at all!” Here is how one social worker described how she reacted when she received this plea from loving sons:

Hurting and sad (after learning their mom’s diagnosis of inoperable cancer), . . . The older sons rushed to the clinic to make me privy to the decision. . . . “Our mother doesn’t know anything and that’s how we want to keep it.” I could see their behavior as denial and discuss the western ethic of patient responsibility. But . . . I knew their children were protecting their mother from what they saw as worse than death: The expectation of nearing death.

(quoted in Kannai, 2008, pp. 146–

454

As this sensitive woman realized, the approach that Kübler-

PEOPLE DO NOT PASS THROUGH DISTINCTIVE STAGES IN ADJUSTING TO DEATH. Most important, Kübler-

Therefore, experts view Kübler-

The More Realistic View: Many Different Emotions; Wanting Life to Go On

People who are dying do get angry, bargain, deny their illness, and become depressed. However, as one psychiatrist argues, it’s more appropriate to view these feelings as “a complicated clustering of intellectual and affective states, some fleeting, lasting for a moment, or a day” (Schneidman, 1976, p. 6). Even when people “know” their illness is terminal, the awareness of “I am dying” may not penetrate in a definitive way (Groopman, 2004; Saeteren, Lindström, & Nåden, 2010). This emotional state, called middle knowledge, is highlighted in this description of Rachel, a 17-

Rachel said . . . that when she is to die, she wanted to be here in Canuck Place (the hospice), surrounded by friends and family . . . and the nurses and doctors that can help her feel not scared. And then she said “but I have another way that I’d like to die . . . sitting on my front porch wrapped in an afghan in a rocking chair and my husband holding my hand.”

(Liben, Papadatou, & Wolfe, 2008, p. 858)

Moreover, as Rachel’s final heart-

Hope, as you can see in the Experiencing the Lifespan box, doesn’t mean hoping for a cure. It may mean wishing you survive through the summer, or live to see your wife’s book published, and not be bedridden before you die. It can mean hoping that your love lives on in your family, or that your life work will make a difference in the world. (Remember, that’s what being generative is all about.) Contrary to what Kübler-

455

Experiencing the Lifespan: Hospice Hopes

It started on a trip to Washington—

During the next few years when my husband’s body became badly bloated, we periodically entered the hospital, to drain off the fluid and accumulate another cocktail of pills. Then, in May 2012, due to a side effect of the medicine, my husband went into kidney failure, and we rushed to the hospital again. Just as the frantic staff was poised to transfer David to endure another heroic intervention, our cardiologist entered the room: “I’m referring your husband to hospice,” he tersely stated. “There is nothing more we can do.” We left the hospital that beautiful late spring afternoon to await death.

Those last few days turned into more than 9 months. With the help of just one pill to control his symptoms, David got much better. He was able to spend that summer and most of the fall walking around on his own. On the December day we finally needed to order a hospital bed, I served chili and chocolate chip cookies for dinner. Then, David just closed his eyes and died.

My husband’s hope in hospice had been to live through the summer, enjoying nature and spending time sitting with me by the pool. He wanted to be alive to hold the third edition of this book, due in November, in his hands. He hated the idea of being bedridden during his final days. Hospice granted David all three of his final wishes.

Heart failure epitomizes that common twenty-

Drawing on Erik Erikson’s theory, we might predict that facing death in our teens or early adult life is uniquely difficult. How can you reach integrity, or the sense you have fulfilled your life goals if you have not found your identity, mastered intimacy, or discovered your generative path? Because death is so appropriate at their life stage, older people don’t show the classic avoidance to death-

In Search of a Good Death

Insights come from turning to religious sources. From the Old Testament (Spronk, 2004) to Hindu traditions (Gupta, 2011), religions agree that death should be celebrated after a long life. Death should be peaceful and sudden, explaining why violent deaths, like suicides or murders, are especially repellent, and why people universally reject the idea of being “tortured” by medical technology at the end of life (Enguidanos, Yonashiro-

456

A good death came to my grandmother, one beautiful summer day. Grandma, at age 98, was just beginning to get slightly frail. One afternoon, before preparing dinner for her visiting grandchildren and great-

Given that our chances of being killed instantly at our doorstep, without frailties at the limit of human life, are almost nil, how can we expand on the above criteria to spell out specific dimensions of a good death? One psychologist offers the following guidelines (Corr, 1991–

We want to minimize our physical distress, to be as free as possible from debilitating pain.

We want to maximize our psychological security, reduce fear and anxiety, and feel in control of how we die.

We want to enhance our relationships and be close emotionally to the people we care about.

We want to foster our spirituality and have the sense that there was integrity and purpose to our lives.

Minimize pain and fear; be close to loved ones; enhance spirituality; feel that life has meaning—

So again, Erikson seems right in saying that the key to accepting death is fulfilling our life tasks and, especially, our generative missions. And in Erikson’s (1963) poetic words, appreciating that one’s “individual life is the accidental coincidence of . . . one lifecycle within . . . history” (p. 268) can be important in embracing death, too:

Barbara turned on the lamp. . . . Her eyes were sunken and her skin was pale. It would not be long, I thought. . . . “Are you afraid?” I asked. “You know, not really,. . . . I have strange comforting thoughts. . . . When fear starts to creep up on me, I conjure up the idea that millions and millions of people have passed away before me, and millions more will pass away after I do . . . I guess if they all did it, so can I.”

(Groopman, 2004, pp. 137–

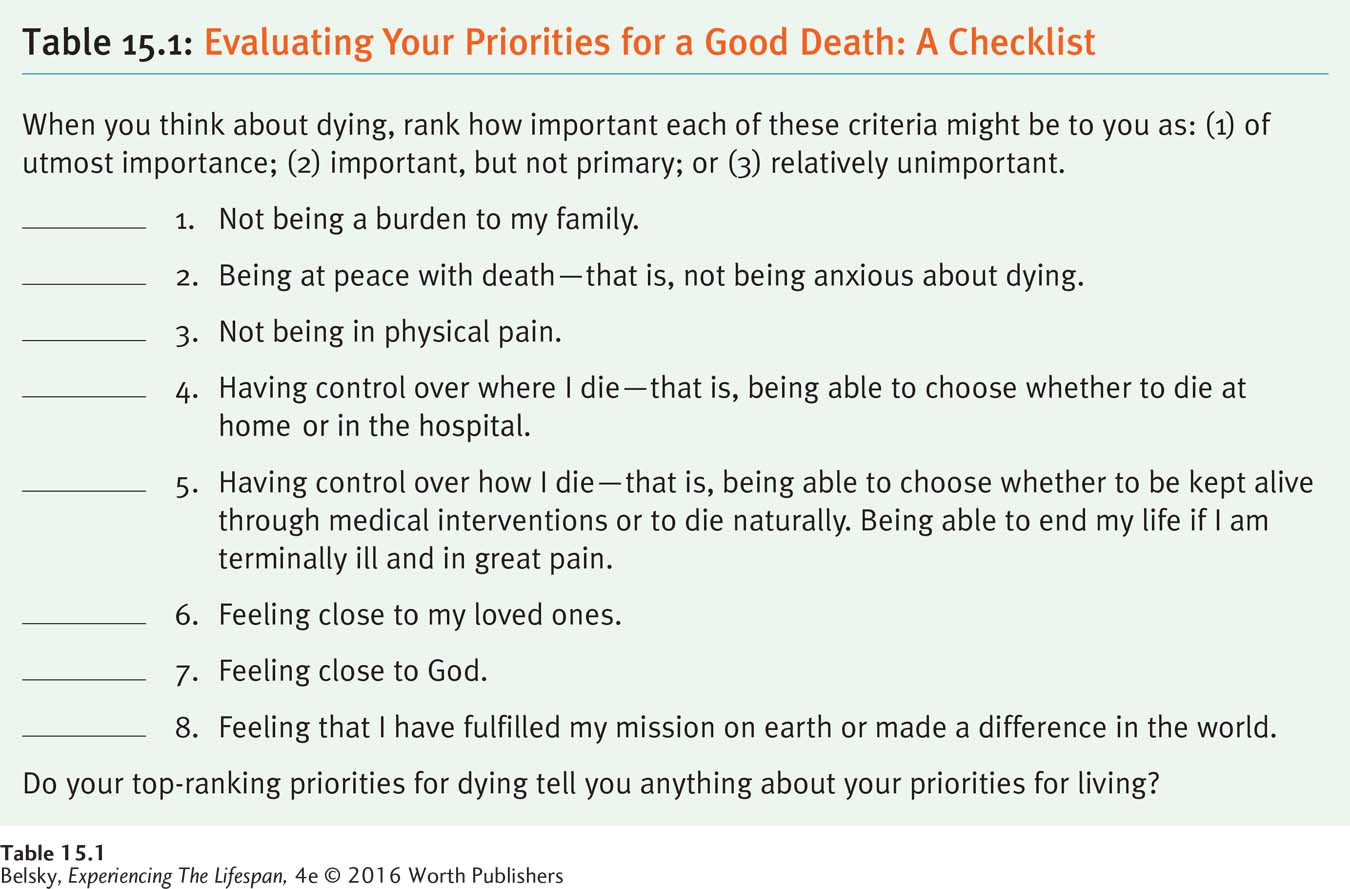

What are your priorities for a good death? Table 15.1 offers an expanded checklist based on the principles in this section, to help you evaluate your top-

457

Hot in Developmental Science: Evolving Ideas About Grieving

Death is just the first chapter in the survivor’s ongoing life story. Although I discussed bereavement in the widowhood section in Chapter 13, let’s now focus on how both psychologists and the public expect that universal experience to proceed (see Jordan & Litz, 2014; Penman and others, 2014).

In the first months after a loved one dies, people are absorbed in mourning, crying; perhaps having trouble eating and sleeping. They might be ruminating about their loved one, carrying around reminders, sharing stories, looking through photos, focusing on the person’s last days. Some people literally sense their loved one’s physical presence in the room (Keen, Murray, & Payne, 2013). Then, after about six months, we expect mourners to recover in the sense of reconnecting to the world (Jordan & Litz, 2014). People still care deeply about their loved one. The person’s memory can be evoked on special times such as anniversaries. But this mental image becomes incorporated into the mourner’s identity as that person travels through life.

Grief patterns, however, are shaped by each society’s unique norms (Neimeyer, Klass, & Dennis, 2014). Some cultures expect people to pine for decades. In others, mourners are supposed to adopt a stoic stiff upper lip. There are variations in grieving in our society, too. Sometimes, people do their mourning before a person’s death, such as when the doctor refers a loved one to hospice or after a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. While we are tempted to accuse these people of being callous (“She went to that party right after her mother died! She hasn’t even been crying much!”), you might be surprised to know it’s “normal” to not have intense symptoms even during the first few months after a significant other dies (Boerner, Mancini, and Bonanno, 2013).

But suppose it’s been more than a year and your bereaved relative still cries continually, feels life is meaningless, and seems incapable of constructing a new life. Can grieving last overly long?

Very cautiously, the framers of our Western psychiatric diagnostic manuals answer yes. When the person’s symptoms continue unabated or become more intense after 6 months to a year, and that individual shows no signs of reconnecting with the world, mental health workers can diagnose a condition labeled persistent complex bereavement-

458

This new diagnosis is controversial, in part because it risks reclassifying that normal life event called mourning as a pathological state. Furthermore, aren’t some deaths so “bad” that prolonged grief is normal—

A Small, Final Note on Mourning a Child

When I worked in a nursing home, I realized that a child’s death can be more upsetting than any other loss. It doesn’t matter whether their “baby” dies at age 6 or in his sixties, people have special trouble coping with that unnatural event (Hayslip & Hansson, 2003). While people do eventually construct a fulfilling life, in one study, even after 4 years, many bereaved parents still showed symptoms of prolonged grief, continually yearning for their child (McCarthy and others, 2010).

A child’s death may evoke powerful feelings of survivor guilt: “Why am I still alive?” If the death occurred suddenly due to an accident, there is disbelief and possibly guilt at having failed in one’s mission as a parent: “I couldn’t protect my baby!” (See Cole & Singg, 1998.) If the death was expected—

When a child has inoperable cancer and seems to understand that he is dying, does it help for parents to discuss death with this daughter or son? To explore this question, Swedish researchers interviewed every family who had lost a child to cancer in that country over several years (Kreicbergs and others, 2004). No parent who reported having a conversation about death with an ill daughter or son had any regrets. In contrast, more than half of the mothers and fathers who believed that their child understood what was happening but never discussed this topic felt guilty later on.

Other research has a similar message: If parents feel satisfied that they said goodbye to their child, this helps lessen the pain. Moreover, not discussing what is happening can produce enduring regrets:

“I wish I had him back so that we could hug and kiss and say goodby” (said one anguished mother). “We never said good-

(quoted in Wells-

What else helps grieving parents cope? In this situation, it helps not to sever the attachment bond to your child.

I talk to her . . . every night. . . . I just say . . . I’m so sorry for what you had to go through, but mommy is so proud of you.

I’d . . . get his ashes and sit . . . and rock. I’ll . . . kiss his little container thing and try to say good night to him every night when I go to bed.

(quoted in Foster and others, 2011, pp. 427, 428, 429, 432)

Another bereaved parent in a South American study went further:

A month had gone by since Matais’s death and I went to the hospital to give encouragement to a mother whose son was dying. . . . This is the way I honor Matais. There I meet him; there I feel him present. I immortalized him by working as a volunteer. Matais is immortalized in the things I do, in the good, in the beautiful things.

(Adapted from Vega, Rivera, & González, 2014, p. 171)

Actually, experts believe the key to recovering from terribly unfair deaths depends on finding new meaning in one’s disrupted life story, and so restoring the idea that the universe is predictable and fair (Neimeyer, Klass, & Dennis, 2014). Grieving parents report they turned the corner when they used their tragedy as a redemption sequence to help keep their child’s memory alive. Some families find solace in donating their sons’ or daughters’ organs to help others survive, or they may adopt a child’s life passions, for instance by deciding to agitate for environmental change. As in the example above, parents may devote their lives to counseling families with an ill child (Vega, Rivera, & González, 2014). People transform bad deaths into love by working at suicide hotlines, or establishing websites to crusade against drunk driving, agitating for better fire safety laws, creating beautiful art-

459

These examples have lessons for all of us in surviving bereavement. Give your loved one a good life. Provide the best possible death. Draw on your loss to grow as a person and enrich other people’s lives.

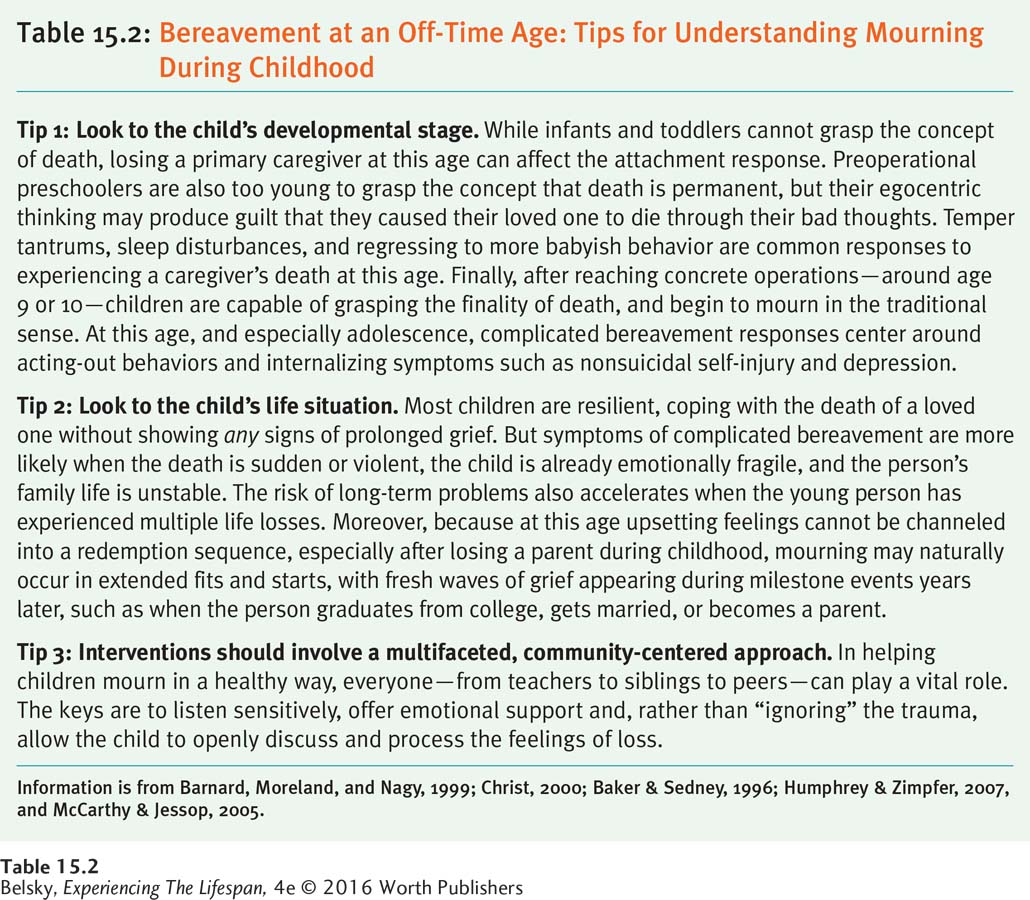

Table 15.2 expands on the topic of bad death by exploring another off-

460

This next section explores how the health-

Tying It All Together

Question 15.4

Sara is arguing that Kübler-

People who are dying do not necessarily want to talk about that fact.

People do not go through “stages” in adjusting to impending death.

People who are dying simply accept that fact.

c

Question 15.5

If your uncle has recently been diagnosed with advanced lung cancer, he should feel (many different emotions/only depressed/only angry), but in general, he should have (hope/a lot of anger).

many different emotions; hope

Question 15.6

Jose says he feels comforted that his beloved uncle had a good death. Which statement is least likely to apply to this man:

Jose’s uncle died peacefully after a long life.

Jose’s uncle was religious.

Jose’s uncle died surrounded by loving attachment figures.

Jose’s uncle felt he had achieved his missions in life.

b

Question 15.7

Imagine you are a psychologist, and a patient comes to your office suffering from prolonged grief. Based on this section, in a sentence, describe your main treatment goal.

Your goal is to restore the person’s sense of meaning in life, ideally by helping that individual transform her loss into a redemption sequence.