15.4 The Health-

How does the health-

What’s Wrong with Traditional Hospital Care for the Dying?

Most of us will die in a hospital (Prevost & Wallace, 2009). But social scientists have known for a half-

The researchers found that, when a person was admitted to the hospital, nurses and doctors set up predictions about what pattern that individual’s dying was likely to follow. This implicit dying trajectory, then governed how the staff acted.

The problem was that dying trajectories could not be completely predicted. When someone mistakenly categorized as “having months to live” was moved to a unit in the hospital where she was not monitored, this mislabeling tended, not infrequently, to hasten death. An interesting situation happened when someone was expected to die soon and then lived on. Doctors might call loved ones to the bedside to say goodbye, only to find that the person began to improve. This “final goodbye” scenario could play out time and time again. The paradox was that if dying was “off schedule,” living might be transformed into a negative event!

One patient who was expected to die (quickly) had no money, but started to linger indefinitely (being paid for as a charity patient in the hospital). The money problem, however, created much concern among both family members and the hospital administrators. . . . The doctor continually had to reassure both parties that the patient (who lived for six weeks more) would soon die; that is, to try to change their expectations back to “certain to die on time.”

(Glaser & Straus, 1968, pp. 11–

461

The bottom line is that deaths don’t occur according to a programmed timetable. Hospitals are structured according to the assumption that they do. This incompatibility makes for a messy dance of terminal care.

Unfortunately, since this research was conducted, the situation has not changed. According to one review of hospital records spanning 1996 to 2010, the odds of health-

One reason is that, today, patients do not spend weeks or months in a hospital. They often enter this setting when they are within days of death. Therefore, the health-

Disagreements between members of the health-

What underlies these conflicts is our quantum leap death-

We were realizing that we were going to hurt him [a 40-

(quoted in Good and others, 2004, p. 945)

Today, medical workers are faced with agonizing ethical choices: How long do you vigorously wage war against death, and when should you say, “enough is enough”? Shifting from the cure-

462

INTERVENTIONS: Providing Superior Palliative Care

Palliative care, refers to any strategy designed to promote dignified dying. Palliative care includes educating health-

Educating Health-

In recent decades, end-

We need to do more (Smith & Hough, 2011). In one hospital survey, although nurses reported dealing with death on a daily basis, fewer than half said they had formal training in end-

The result of this anxiety is that we sometimes get physicians who (perhaps out of their own fear) decide to take Kübler-

Changing Hospitals: Palliative-

A palliative-

Families give palliative care high marks, compared to traditional end-

The global view, however, is bleak. Even in affluent nations—

463

State-

Unhooking Death from Doctors and Hospitals: Hospice Care

This is the philosophy underlying the hospice movement, which gained momentum in the 1970s, along with the natural childbirth movement. Like birth, hospice activists argued, death is a natural process. We need to let this process occur in the most pain-

Hospice workers are skilled in techniques to minimize patients’ physical discomfort. They are trained in providing a humanistic, supportive psychological environment, one that assures patients and family members that they will not be abandoned in the face of approaching death (Monroe and others, 2008).

In many developed nations, hospice care is mainly delivered in a freestanding facility called a hospice. The main focus of the United States hospice movement is on providing backup care that allows people to die with dignity at home. As occurred with my husband, and as you can read in the Experiencing the Lifespan box below, multidisciplinary hospice teams go into the person’s home, offering care on a part-

Experiencing the Lifespan: Hospice Team

What is hospice care really like? For answers, here are some excerpts from an interview I conducted with the team (nurse, social worker, and volunteer coordinator) who manages our local hospice.

Usually, we get referrals from physicians. People may have a wide community support system or be new to the area. Even when there are many people involved, there is almost always one primary caregiver, typically a spouse or adult child.

We see our role as empowering families, giving them the support to care for their loved ones at home. We go into the home as a team to make our initial assessment: What services does the family need? We provide families training in pain control, in making beds, in bathing. A critical component of our program is respite services. Volunteers come in for part of each day. They may take the children out for pizza, or give the primary caregiver time off, or just stay there to listen.

Families will say initially, “I don’t think I can stand to do this.” They are anxious because it’s a new experience they have never been through. At the beginning, they call a lot. Then, you watch them gain confidence in themselves. We see them at the funeral and they thank us for helping them give their loved one this experience. Sometimes, the primary caregiver can’t bear to keep the person at home to the end. We respect that, too.

The whole thing about hospice is choice. Some people want to talk about dying. Others just want you to visit, ask about their garden, talk about current affairs. We take people to see the autumn leaves, to see Santa Claus. Our main focus is: What are your priorities? We try to pick up on that. We had a farmer whose goal was to go to his farm one last time and say goodbye to his tractor. We got together a big tank of oxygen, and carried him down to his farm. We have one volunteer who takes a client to the mall.

We keep in close touch with the families for a year after, providing them counseling or referring them to bereavement groups in the community. Some families keep in contact with notes for years. We run a camp each summer for children who have lost a parent.

We have an unusually good support system among the staff. In addition to being with the families at 3 a.m., we call one another at all times of the night. Most of us have been working here for years. We feel we have the most meaningful job in the world.

464

Entering a U.S. hospice program is simple. It requires a physician to certify that the person is within six months of death. Home hospice care is less expensive than traditional end-

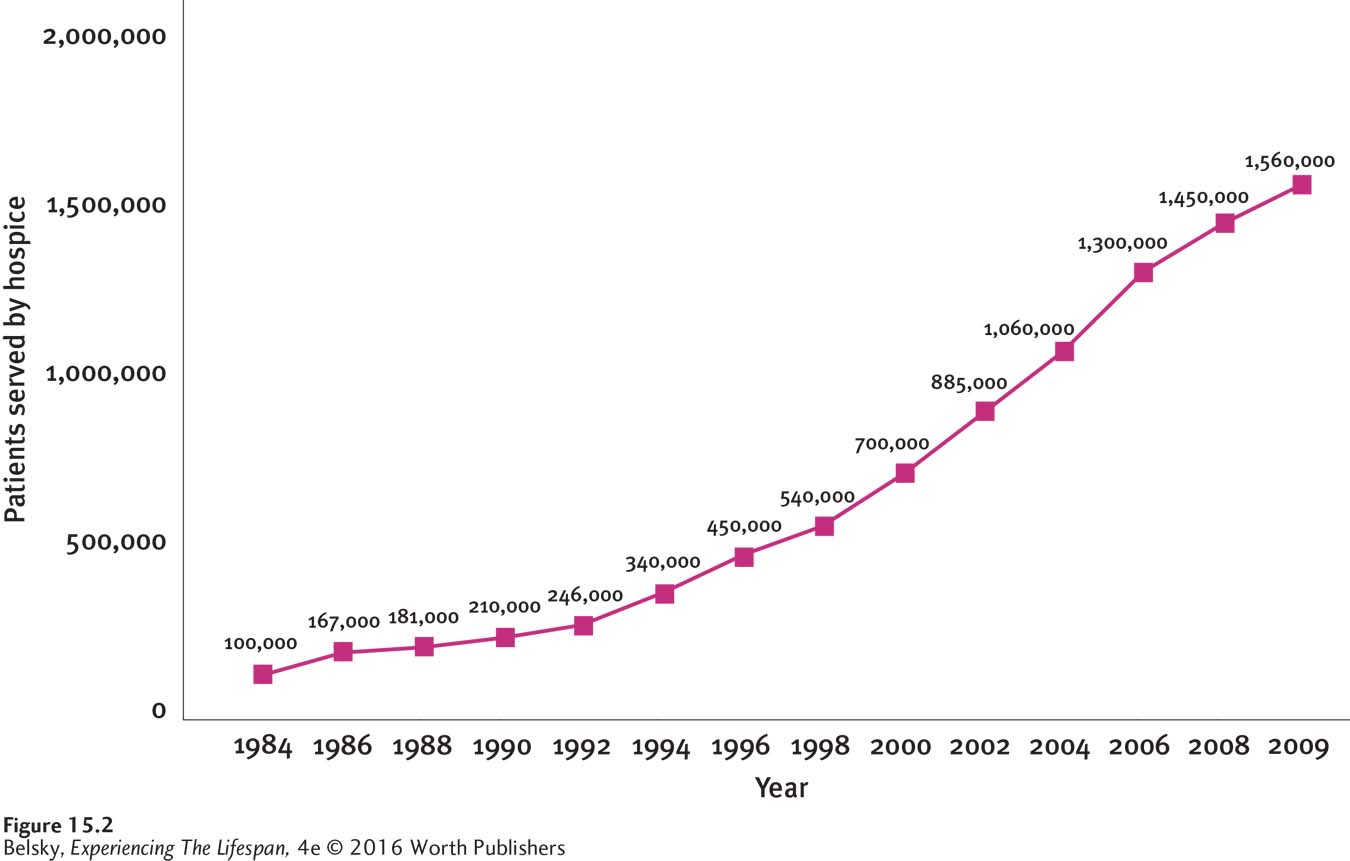

As you can see in Figure 15.2, in recent decades, the U.S. hospice movement has mushroomed. By 2009, roughly 2 in 5 U.S. deaths occurred in hospice care. What is the hospice experience really like?

Charting the U.S. Hospice Experience

Imagine that your doctor has just made the pronouncement: “I’m referring your spouse or parent to hospice. There is nothing more we can do.” You must simultaneously deal with the shock of grieving and embark on a difficult, uncharted path. Passionate to offer your loved one this final demonstration of love, you are incredibly anxious about what lies ahead. What can you expect about the person’s pathway to death?

The answer partly depends on the illness. If the disease is cancer, expect a more precipitous decline. With congestive heart failure or pulmonary disease, the transition to serious ADL problems is apt to be slower during the next days and weeks. Some people enter hospice bedridden and spend their final days comatose. Others, like my husband, are fully alert and able to perform basic ADL activities until their last moments of life (Harris and others, 2013). This variation partly explains why, although the average hospice stay is roughly two weeks, 1 in 10 U.S. patients spends close to a year in hospice care (Sengupta and others, 2014).

This uncertainty is scary, but your main fear is seeing your loved one suffer. The box full of medications you just got from the hospice team is frightening. Without any nursing training, will you be able to control your family member’s pain?

Actually, issues relating to pain control rank among hospice caregivers primary concerns: People worry about leaving the person in agony, or they may fear that that final dose of morphine hastened death (Oliver and others, 2013; Kelley and others, 2013). As one person reported: “She (dying loved one) has chronic pain. The morphine was in an unusual bottle and I was afraid to give her too much or too little and the dropper wasn’t working. It was very scary” (quoted in Kelley and others, 2013, p. 679).

465

These worries are not unrealistic. In one survey, 2 out of 3 U.S. hospice providers cited medication management as their most problematic issue. One in three reported frequently encountering problems in this area as they struggled to help families provide care (Joyce & Lau, 2013).

Charting the Barriers to Hospice

This discussion brings up the hurdles to hospice. As I mentioned earlier, hope is the main emotion people feel when facing a terminal disease. Entering hospice means confronting the reality, “I am going to die.” Family members are naturally reluctant to bring up hospice, because they, too, may want to urge undergoing that one last curative intervention that allows a loved one to survive.

The same reluctance applies to the hospice gatekeeper—

Another impediment relates to everyone’s misconceptions about hospice care. People are not aware that patients can still receive curative interventions after entering hospice, or that it’s possible to survive for months in hospice with a fairly good quality of life (see the Experiencing the Lifespan box on page 455). Particularly, minority groups may not understand that in the United States, Medicare pays for hospice (Frey and others, 2013) or realize that hospice care occurs at home (Enguidanos, Yonashiro-

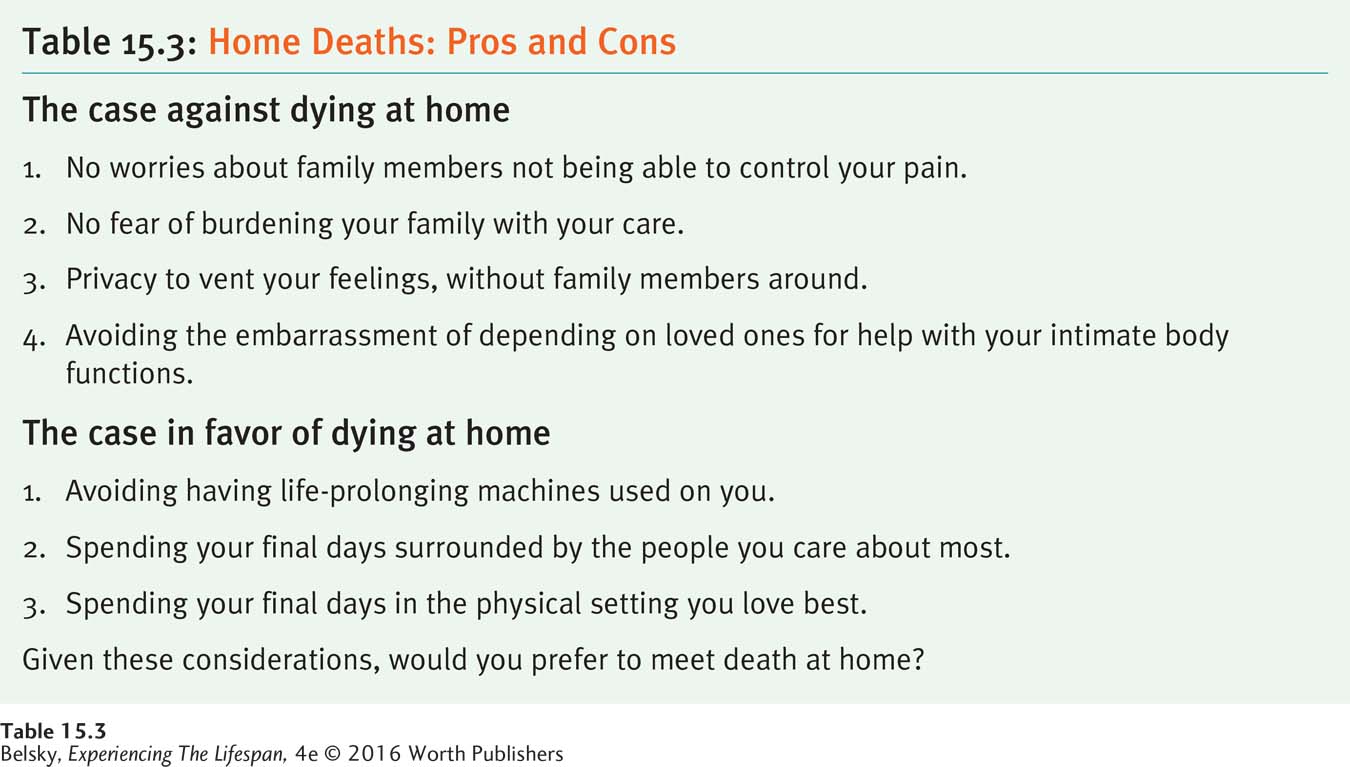

Even when patients are aware that their illness is fatal, they may be less than thrilled to have loved ones care for them during their final weeks of life. Imagine being totally taken care of by your family when you have a terminal disease. You don’t have any privacy. Loved ones must bathe you and dress you; they must care for your every need. You may be embarrassed about being seen naked and incontinent; you may want time alone to vent your anguish and pain. In a hospital (or inpatient hospice), care is impersonal. At home, there is the humiliation of having to depend on the people you love most for each intimate bodily act.

Most importantly, care by strangers equals care that is free from guilt. As I described earlier in this chapter, when people are approaching death, they often want to emotionally protect their loved ones—

This explains, why, in a rare interview study conducted with people receiving inpatient hospice care in Australia, patients’ main worries centered around loved ones. Yes, people said, moving to hospice signaled a depressing step closer to death. But they were relieved to no longer be burdening their families: “My husband is very quiet. . . . If he feels he cannot cope, I would rather be in here if that gives him a chance to come here, spend some time and then go home and get his head together,” reported one woman. A man appreciated the privacy involved in getting care from strangers. “It’s going with a little bit of dignity . . . and not in a mess, . . . and not being a frightening sight to those who are sitting there” (quoted in Broom & Kirby, 2013, p. 504).

This need to preserve dignity (or face) with one’s family, may explain why U.S. hospice programs are rejected among the very cultural group historically most committed to family care. When researchers polled Chinese heritage elderly living in San Francisco, people reacted with horror when they learned hospice involves care at home. One woman summed up the general feelings when she said, “If I am dying I become very grumpy; it’s a good idea to send me to a nursing home” (quoted in Enguidanos, Yonashiro-

466

Table 15.3 summarizes these section points in “a pros and cons of home care” chart. Now that I have surveyed the health-

Tying It All Together

Question 15.8

In a sentence, describe to a friend the basic message of the classic research describing the various dying trajectories discussed on pages 480–

Although medical personnel set up predictions about how patients are likely to die, death doesn’t always go according to schedule—

Question 15.9

Based on this section, which statement most accurately reflects doctors’ reactions to the terminally ill? (Pick one.) (a) Doctors are insensitive to dying patients’ needs, or (b) Doctors feel terribly upset when a patient is dying, but may feel forced to use modern technologies to “prolong” death.

b

Question 15.10

Carol’s husband has just been referred to hospice. If this couple lives in the United States, you can predict (pick FALSE statement):

Carol will be caring for her spouse at home.

If Carol’s spouse has heart disease, he may decline more slowly than if he has cancer.

Carol may be terribly worried about her ability to control her husband’s pain.

Carol will spend a good deal of money on hospice care.

d

Question 15.11

Melanie is arguing that there’s no way she will die in a hospital. She wants to end her life at home, surrounded by her husband and children. Using the information in this section, convince Melanie of the down side to spending her final days at home.

Here’s what you might say to Melanie: Would you feel comfortable about burdening your family 24/7 with the job of nursing you for months or having them manage the health crises that would occur? How would you feel having loved ones see you naked and incontinent—