15.5 The Dying Person: Taking Control of How We Die

In this section, I’ll explore two strategies people can use to control their final passage and so promote a “good death.” The first is an option that our society strongly encourages: People should make their wishes known in writing about their treatment preferences should they become mentally incapacitated. The second approach is controversial: People should be allowed to get help if they want to end their lives.

Giving Instructions: Advance Directives

467

An advance directive, is the name for any written document spelling out instructions with regard to life-

In the living will, mentally competent individuals leave instructions about their treatment wishes for life-

prolonging strategies should they become comatose or permanently incapacitated. Although people typically fill out living wills in order to refuse aggressive medical interventions, it is important to point out that this document can also specify that every heroic measure be carried out. In a durable power of attorney for health care, individuals designate a specific person, such as a spouse or a child, to make end-

of- life decisions “in their spirit” when they are incapable of making those choices known. A Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order, is filled out when the sick person is already mentally impaired, usually by the doctor in consultation with family members. This document, most often placed in a nursing home or hospital chart, stipulates that, if a cardiac arrest takes place, health-

care professionals should not try to revive the patient. A Do Not Hospitalize (DNH) order, is specific to nursing homes. It specifies that, during a medical crisis, a mentally impaired resident should not be transferred to a hospital for emergency care.

Advance directives have an admirable goal. Ideally, they provide a road map so that family members and doctors are not forced to guess what care the permanently incapacitated person might want. However, there are issues with regard to these documents too.

One difficulty is that people are naturally reluctant to think about their death (Ko & Lee, 2014). Do you or your parents have an advance directive? Even in the Netherlands, where people can choose to take their lives, less than 1 in 10 people does (as reported in van Wijmen and others, 2014).

The good news is that most older adults in the United States now have advance directives, a quantum leap from the situation a decade ago (Silveira, Wiitala, & Piette, 2014). But minorities and low-

There are also serious problems with the most well-

While we might think the solution would be to come up with specific checklists (“I don’t want to be on a ventilator, but I do want a feeding tube”), can we expect people to make these detailed decisions? How many of you really know what being on a ventilator or having a feeding tube entails? Moreover, while you might say “no heroic measures” if you are healthy, your decisions are apt to be different when you are battling a fatal disease. Therefore, the best strategy is to have a series of evolving discussions with loved ones, and then choose a designated family member who, in consultation with the physician, makes the final choice (see, McMahan and others, 2013; van Wijmen & others, 2014).

468

This means the best advance directive is a durable power of attorney for health care. Granted, deciding on a single family member to carry out one’s wishes can lead to jealousy. (“Why did Mom choose my brother and not me?”) It doesn’t ensure mistakes won’t occur. Suppose after giving your “so called” reliable daughter power of attorney, that child elopes with a money-

By now, some readers may be getting uneasy, not about keeping people alive too long, but about the opposite problem—

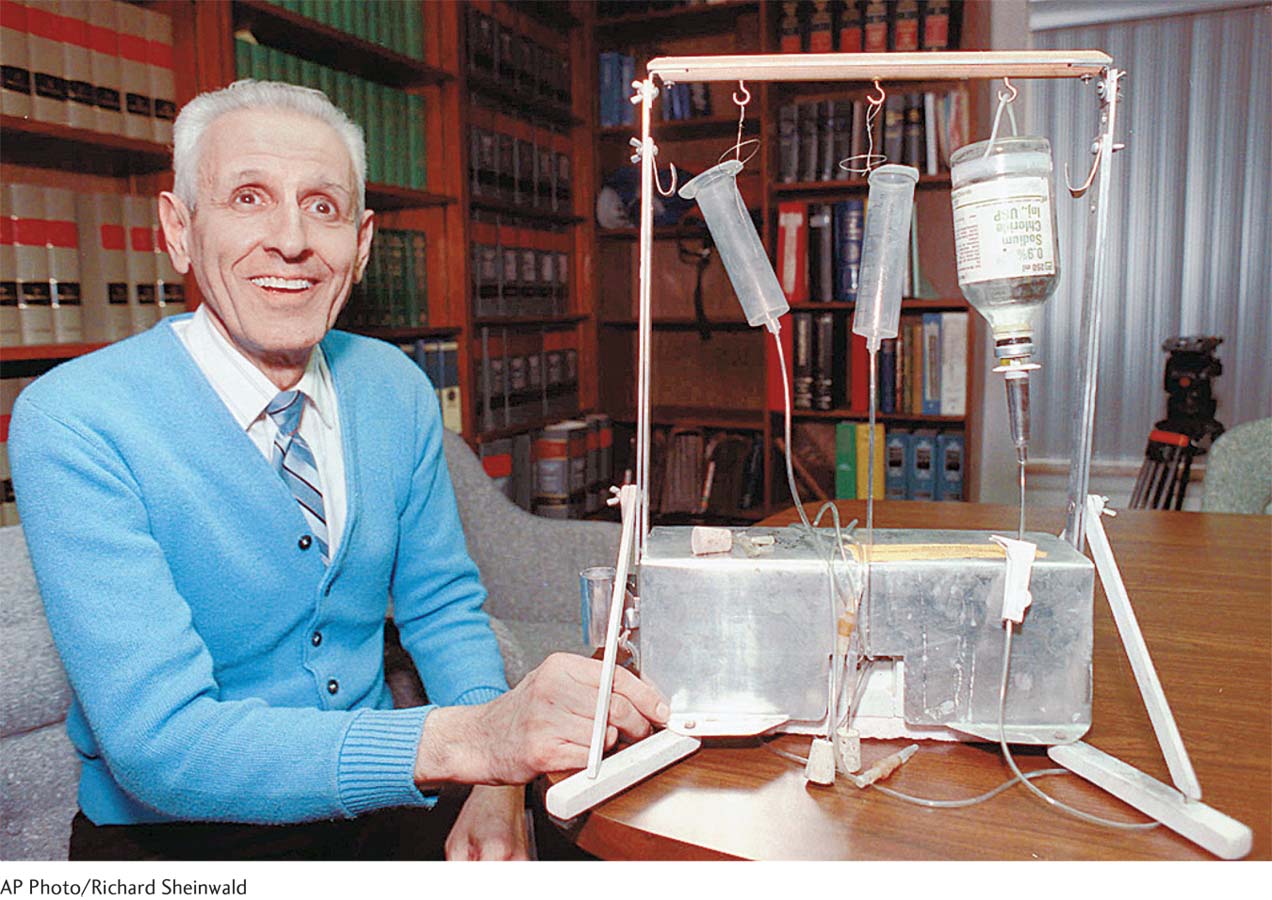

Deciding When to Die: Active Euthanasia and Physician-

Dr. Cox, a British rheumatologist, had a warm relationship with Mrs. Boyles, who had been his patient for 13 years. Mrs. Boyles was terminally ill, in excruciating pain and begged Dr. Cox to end her life: “Her pain was . . . grindingly severe. . . . [It] did not respond to increasingly large doses of opioids. Dr. Cox had reassured her that she would not be allowed to suffer terrible pain during her final days but was unable to honor that pledge. . . . As an act of compassion, he injected two ampoules of potassium chloride (a fatal drug). . . . The patient died a few minutes later peacefully in the presence of her (grateful) sons. . . .” Then the ward sister, out of a sense of duty . . . reported the action to the police. Told to “disregard the doctor’s motives” but only rule on his “intent to kill,” a jury . . . convicted Dr. Cox “amid scenes of great emotional distress in the court.”

(as reported in Begley, 2008; quotes are from pp. 436 and 438)

How do you feel about this doctor’s decision, the reaction of his nurse, and the jury’s judgment? If you were like many people in Great Britain, you would have been outraged, believing that Dr. Cox was a hero because he acted on his mission to relieve human suffering rather than follow an unjust law (recall Kohlberg’s post-

Let’s first make some distinctions. Passive euthanasia, withdrawing potentially life-

As the judge in the above trial spelled out, the distinction between the two types of euthanasia lies in intentions (Dickens, Boyle, & Ganzini, 2008). When we withdraw some heroic measure, we don’t specifically wish for death. When doctors give a patient a lethal dose of a drug or, as in physician-

Although active euthanasia is almost universally against the law, surveys suggest practices that hasten death do routinely occur (Chambaere and others, 2011; Seale, 2009). To take a classic example, doctors may sedate a dying patient beyond the point required for pain control, and so “accelerate” that person’s death (Cellarius, 2011). Polls show increasingly widespread public acceptance of active euthanasia in Western E.U. nations over the past 30 years. But this is not the case in Central and Eastern Europe, where significant fractions of citizens still believe terminating the lives of people is never justified (Cohen and others, 2013). Why?

469

One reason is that killing violates the principle that only God can give or take a life. So the fact that in Central and Eastern Europe people are more apt to be religious partly explains this East–

Critics fear that legalizing euthanasia may open the gates to allowing doctors and families to “pull the plug” on people who are impaired but don’t want to die (Verbakel & Jaspers, 2010). Even when someone requests help to end his life, a patient might sometimes be pressured into making that decision by unscrupulous relatives who are anxious to get an inheritance and don’t want to wait till the person dies. Governments might be tempted to push through euthanasia legislation to spare the expense of treating seriously disabled citizens—

Older people, unfortunately, are apt to be against physician-

Another issue relates to where to draw the line. Should we allow people to kill themselves when they have a painful chronic condition, but may not be fatally ill? Suppose the person is simply chronically depressed. Can permitting suicide ever be an ethically acceptable choice (see Berghmans, Widdershoven, & Widdershoven-

There are excellent arguments on the other side. Should patients be forced to unwillingly endure the pain and humiliation of dying when physicians have the tools to mercifully end life? Knowing the agony that terminal disease can cause, is it humane to stand by and let nature take its course? Do you believe that legalizing active euthanasia or physician-

A Looming Social Issue: Age-

There obviously is an age component to the “slippery slope” of withholding care. As I suggested earlier, people with DNR or DNH orders in their charts are typically elderly, near the end of their natural lives. We already use passive euthanasia at the upper end of the lifespan on a case-

Daniel Callahan (1988), a prominent biomedical ethicist, argues that the answer must be yes. According to Callahan, there is a time when “the never-

After a person has lived out a natural lifespan, medical care should no longer be oriented to resisting death. While stressing that no precise cutoff age can be set, Callahan puts this marker at around the eighties. This does not mean that life at this age has no value, but rather that when people reach their old-

old years, death in the near future is inevitable and this process cannot be vigorously defied. The existence of medical technologies capable of extending the lives of elderly persons who have lived out a natural lifespan creates no presumption that the technologies must be used for that purpose. Callahan believes that the proper goal of medicine is to stave off premature death. We should not become slaves to our death-

defying technology by blindly using each intervention on every person, no matter what that individual’s age.

470

Age-

Do you think Callahan is “telling it like it should be” from a logical, rational point of view, or do his proposals give you chills? Should we rely on markers such as life expectancy or quality of life to allocate who does or doesn’t deserve to get care?

Whatever your answer to these compelling questions, you might notice that this chapter is devoted to one core lifespan concern. As we approach death, our life comes full circle, and we care only about what mattered during our first year of life—

Tying It All Together

Question 15.12

Your mother asks you whether she should fill out an advance directive. Given what you know about these documents, what should your answer be?

Go for it! But fill out a living will.

Go for it! But you need to regularly discuss your preferences with each of us and complete a durable power of attorney.

Avoid advance directives like the plague because your preferences will never be fulfilled.

b

Question 15.13

Latoya and Jamal are arguing about legalizing physician-

Jamal’s case: We are free to make decisions about how to live our lives, so it doesn’t make logical sense that we can’t decide when our lives should end. Plus, it’s cruel to torture fatally ill people, forcing them to suffer fruitless, unwanted pain when we can easily provide a merciful death. Latoya’s argument: I’m worried that greedy relatives might pressure ill people into deciding to die “for the good of the family” (that is, to save the family money). I believe that legalizing physician-

Question 15.14

Poll your class: How would your fellow students vote if they were on the jury deciding Dr. Cox’s case? If you were the ward nurse, would you have reported this doctor’s decision to the police?

Here your answers may vary in interesting ways. Enjoy the discussion!