1.2 Setting the Context

How does being born in a particular historical time affect our lifespan journey? What about our social class, cultural background, or that basic biological difference, being female or male?

The Impact of Cohort

Cohort refers to our birth group, the age group with whom we travel through life. In the vignette, you can immediately see the heavy role our cohort plays in influencing adult life. Susan reached adult life in 1960, when women married in their early twenties and typically stayed married for life. Jamila came of age during the final decade of the twentieth century, when women began to feel they needed to get their careers together before finding a mate. As an interracial couple, Matt and Jamila are taking a life path unusual even for today! Because they are in their late forties, this couple is at an interesting cutting point. They are traveling through life after that huge bulge in the population called the baby boom.

The baby boom cohort, defined as people born from 1946 to 1964, has made a huge impact on the Western world as it moves through society. The reason lies in size. When soldiers returned from World War II and got married, the average family size ballooned to almost four children. When this huge group was growing up during the 1950s, families were traditional, with the two-

The cohorts living in the early twenty-

Changing Conceptions of Childhood

At age ten he began his work life helping … manufacture candles and soap. He … wanted to go to sea, but his father refused and apprenticed him to a master printer. At age 17 he ran away from Boston to Philadelphia to search for work.

His father died when he was 11, and he left school. At 17 he was appointed official surveyor for Culpepper County in Virginia. By age 20 he was in charge of managing his family’s plantation.

(Mintz, 2004)

Who were these boys? Their names were Benjamin Franklin and George Washington.

Imagine being born in Colonial times. In addition to reaching adulthood at a much younger age, your chance of having any lifespan would have been far from secure. In seventeenth-

6

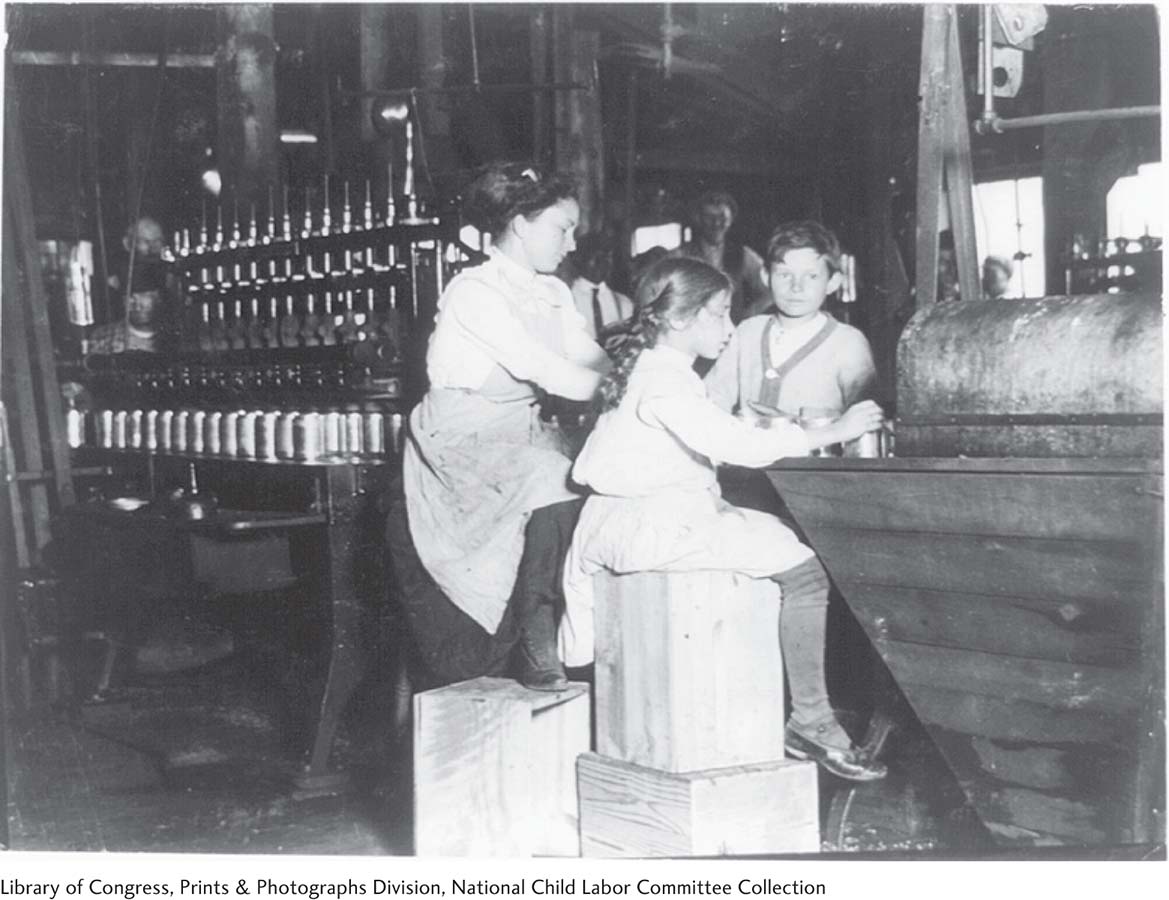

The incredible childhood mortality rates, plus poverty, may have partly explained why child-

In addition, for most of history, people did not have our feeling that childhood is a special life stage (Ariès, 1962; Mintz, 2004). Children, as you saw above, began to work at a young age. During the early industrial revolution, poor boys and girls made up more than a third of the labor force in British mills (Mintz, 2004).

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau spelled out a strikingly different vision of childhood and human life (Pinker, 2011). Locke believed that human beings are born a tabula rasa, a blank slate on which anything could be written, and that the way we treat children shapes their adult lives. Rousseau argued that babies enter life totally innocent; he felt we should shower these dependent creatures with love. However, this message could fully penetrate society only when the advances of the early twentieth century dramatically improved living standards, and we entered our modern age.

One force producing this kinder, gentler view of childhood was universal education. During the late nineteenth century in Western Europe and much of the United States, attendance at primary school became mandatory (Ariès, 1962). School kept children from working and insulated these years as a protected, dependent life phase. Still, as late as 1915, only 1 in 10 U.S. children attended high school; most people entered their work lives after seventh or eighth grade (Mintz, 2004).

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the developmentalist G. Stanley Hall (1904/1969) identified a stage of “storm and stress,” located between childhood and adulthood, which he named adolescence. However, it was during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when President Franklin Roosevelt signed a bill making high school attendance mandatory, that adolescence became a standard U.S. life stage (Mintz, 2004). Our famous teenage culture has existed for only 70 or 80 years!

In recent decades, with many of us going to college and graduate school, we have delayed the beginning of adulthood to an older age. Developmentalists (see Tanner & Arnett, 2010) have identified a new in-

Changing Conceptions of Later Life

In every culture, a few people always lived to “old age.” However, for most of history, largely due to the high rates of infant and childhood mortality, average life expectancy, our fifty-

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, life expectancy in the United States rapidly improved. By 1900, it was 46. Then, in the next century, it shot up to 76.7. During the twentieth century, life expectancy in North America and Western Europe increased by almost 30 years! (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Health United States, 2007.)

7

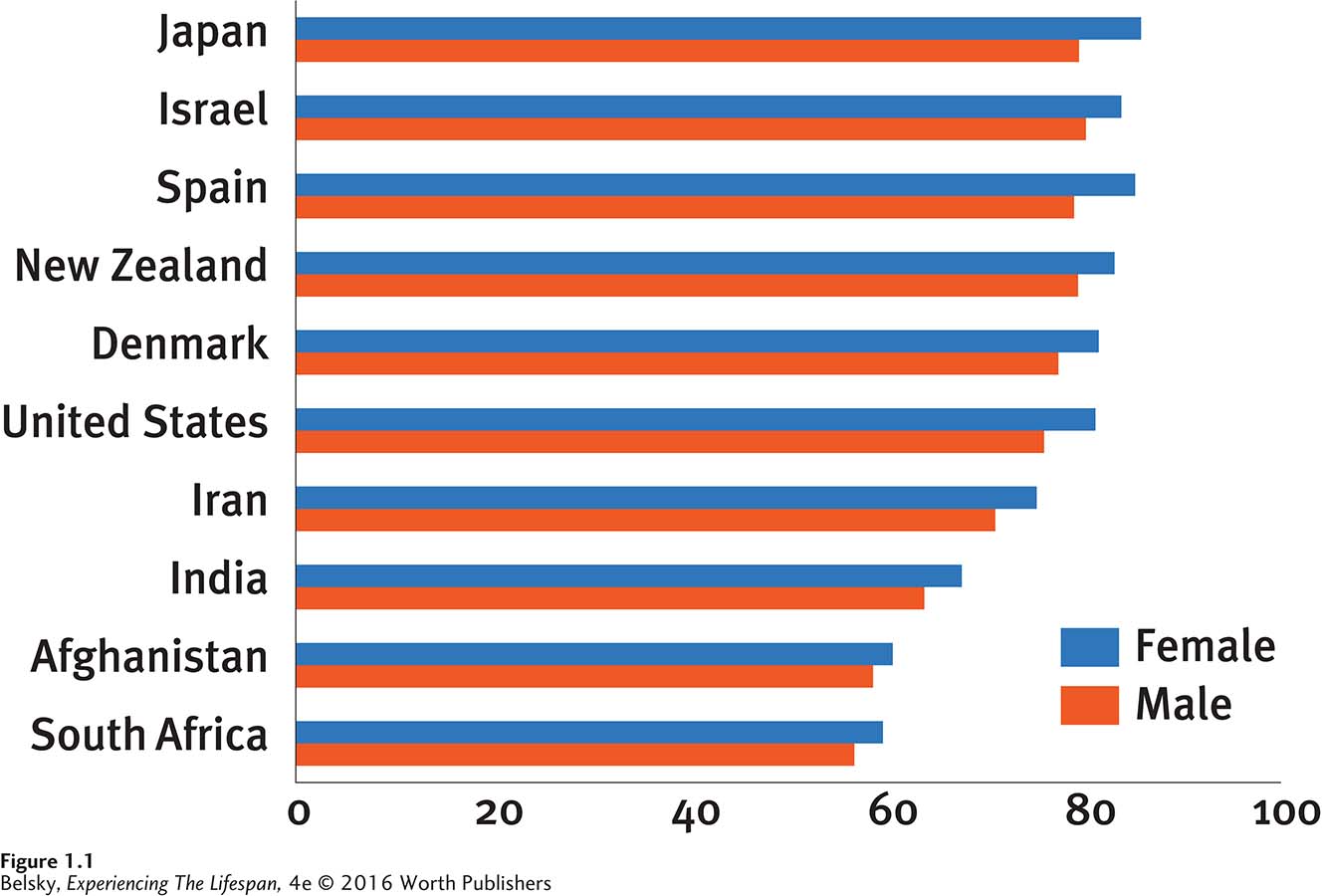

The twentieth-

As you can see in Figure 1.1, the outcome is that today, life expectancies have zoomed into the upper seventies in North America, Western Europe, New Zealand, Israel, and Japan. A baby born in affluent parts of the world, especially if that child is female, now has a good chance of making it close to our maximum lifespan, the biological limit of human life (about age 105).

This extension of the lifespan has changed how we think about every life stage. It has moved grandparenthood, once a sign of being “old,” down into middle age. If you become a grandparent in your forties, expect to be called grandma or grandpa for half of your life! Women can start new careers in their early fifties, given that U.S. females at that age can expect to live on average for roughly 32 more years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Most important, we have moved the beginning of old age beyond age 65.

Today, people in their sixties and even early seventies are often active and relatively healthy. But in our eighties, our chance of being disabled by disease increases dramatically. Because of this, developmentalists make a distinction between two groups of older adults. The young-

Changing Conceptions of Adult Life

If health-

The 1960s “Decade of Protest” included the civil rights and women’s movements, the sexual revolution, and the “counterculture” movement that emphasized liberation in every area of life (Bengtson, 1989). People could have sex without being married. Women could fulfill themselves in a career. We encouraged husbands to share the housework and child care equally with their wives. Divorce became an acceptable alternative to living in an unfulfilling marriage. To have a baby, women no longer needed to be married at all.

Today, with women making up more than half the U.S. labor force, only a minority of couples fit the traditional 1950s roles of breadwinner husband and homemaker wife (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). With roughly one out of two U.S. marriages ending in divorce, we can no longer be confident of staying together for life. While divorce rates are now declining, the Western trend toward having children without being married continues to rise. As of 2013, almost 48 percent of U.S. babies were born to single moms (Hymowitz and others, 2013).

8

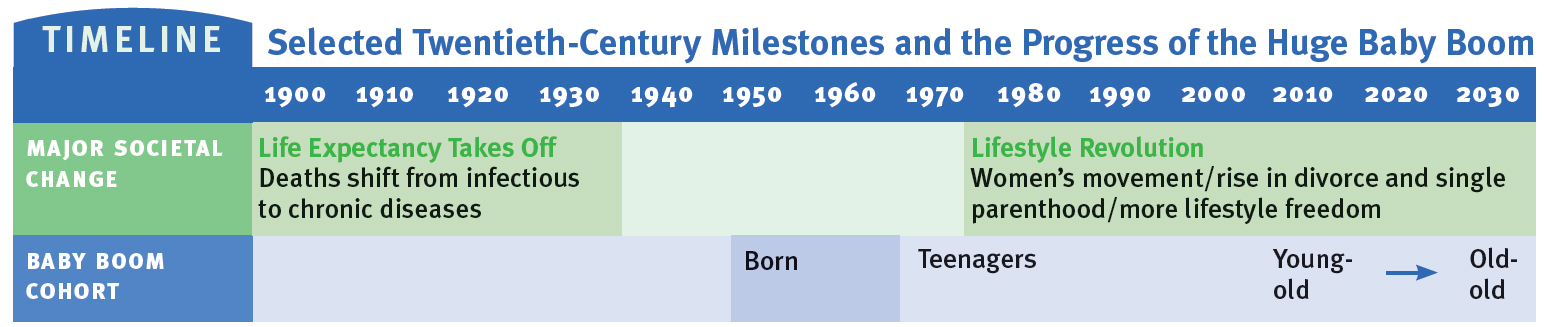

The timeline at the bottom of this page illustrates the twentieth-

But, as history is always advancing, let’s end this section by touching on two twenty-

From Relating in the Real World to Residing in Cyberspace: On-

Meet the Alvin family…. Sandra, a former journalist … has over 800 followers on twitter and keeps an elaborate … blog; their 16-

(quoted in Van Dijck, 2013, p 3)

Julia, … a Sophomore at a … public high school turns texting into a kind of polling. After Julia sends out a text, she is uncomfortable until she gets one back: “I’m always looking for a text that says, “Oh I’m sorry” or “Oh that’s great.” Without this feedback, she says, “It’s hard to calm down.” Julia describes how painful it is to text about her feelings and get no response: “If … they don’t answer me … I’ll text them again “are you mad? … Is everything Ok?”

(adapted from Turkle, 2011, p. 175)

How many of you feel the urge to check Facebook or your cell phone as you are reading these lines? Perhaps, like Sandra, you have followers on Twitter or keep a personal blog, or can relate to Julia’s anxiety when you text and don’t get an immediate response.

9

Cell phones and texting instituted what one expert (Van Dijck, 2013) has labeled our twenty-

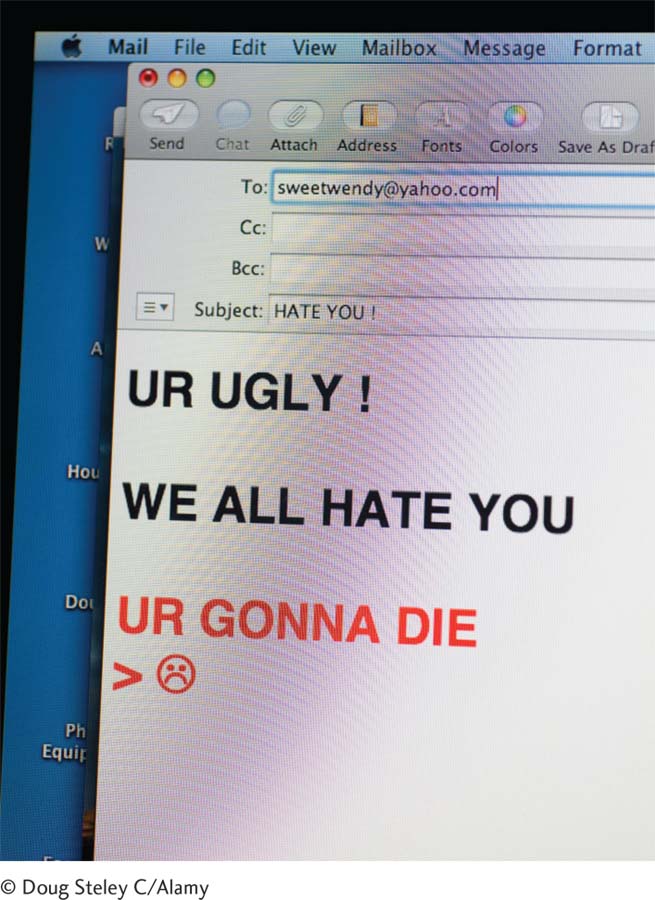

How has Facebook transformed romantic relationships? Does bullying on-

From Living in an Expanding Economy, to Facing Financial Hardship: The Great Recession

I was laid off from my job on April 1st. I’ve used up all my retirement funds and savings. I have never seen anything this bad in this country.

(Sandra K, Cleveland Heights, Ohio)

Welcome to the Great Recession of 2008, which began with the bursting of an 8-

As I’m writing this chapter (in early 2015), the economy has improved in the United States and many European nations. Will the economic landscape turn truly sunny as you are reading these pages? Whatever the answer, our economic situation has an important impact on our journey through life. How exactly does being affluent or poor affect how we develop and behave?

The Impact of Socioeconomic Status

This question brings up the role of socioeconomic status (SES)—a term referring to our education and income—

Developed-

Developing-

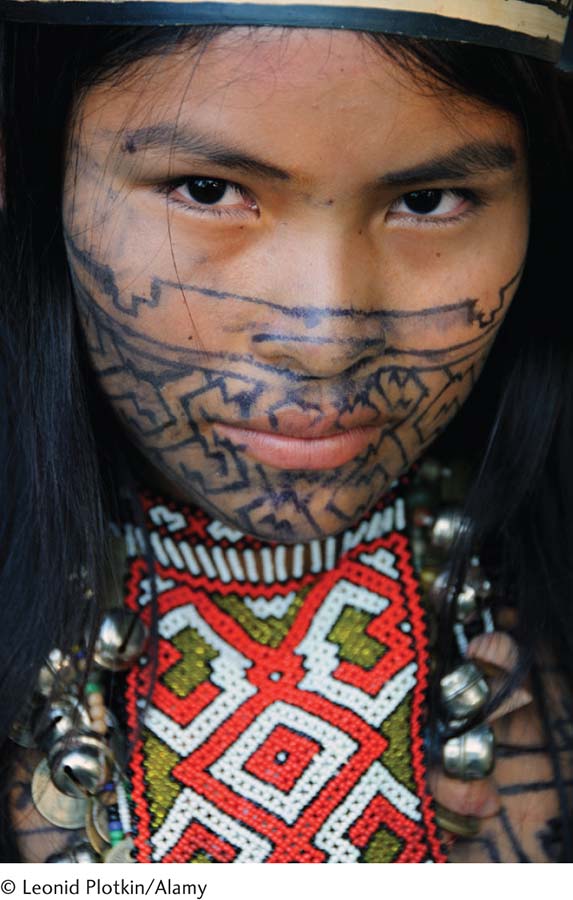

The Impact of Culture and Ethnicity

10

Residents of developing nations often have shorter, more difficult lives. Still, if you visited these places, you might be struck by a sense of community you might not find in the West. Can we categorize societies according to their basic values, apart from their wealth? Developmentalists who study culture answer yes.

Collectivist cultures place a premium on social harmony. The family generations expect to live together, even as adults. Children are taught to obey their elders, to suppress their feelings, to value being respectful, and to subordinate their needs to the good of the wider group.

Individualistic cultures emphasize independence, competition, and personal success. Children are encouraged to openly express their emotions, to believe in their own personal power, to leave their parents, to stand on their own as self-

Imagine how your perspective on life might differ if becoming independent from your parents or honestly sharing your feelings was viewed as an inappropriate way to behave. How would you treat your children, choose a career, or select a spouse? What concerns would you have as you were facing death?

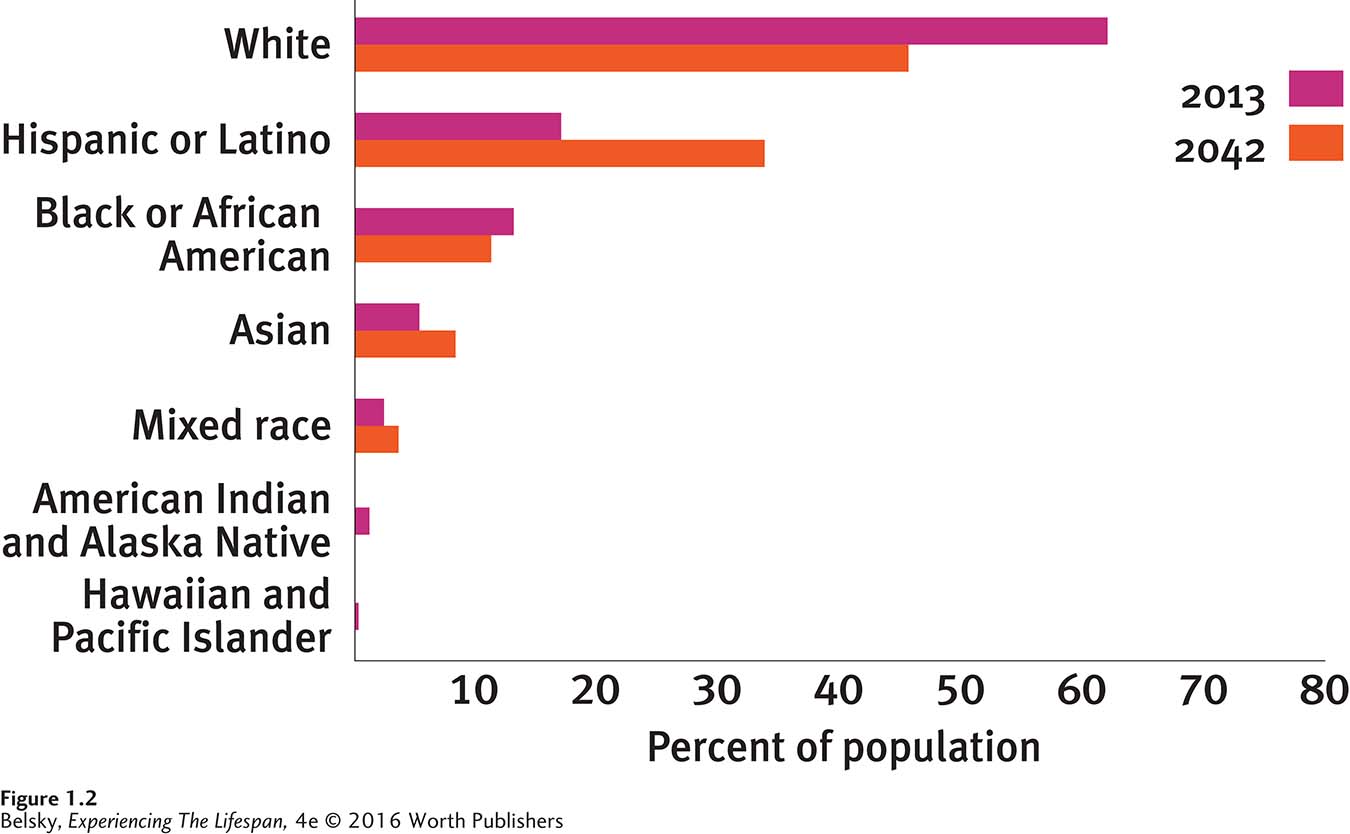

As we scan development around the world, I will regularly distinguish between collectivist and more individualistic societies. I’ll highlight the issues families face when they move from these traditional cultures to the West, and explore research relating to the major U.S. ethnic groups listed in Figure 1.2.

As you read this information, keep in mind that what unites us as people outweighs any distinctions based on culture, ethnicity, or race. Moreover, making diversity generalizations is hazardous because of the diversity that exists within each nation and ethnic group. In the most individualistic country (no surprise, that’s the United States), people have a mix of collectivist and individualistic worldviews. Due to globalization, traditionally collectivistic cultures, such as China and Japan, now have developed more individualistic, Western worldviews.

If the census labels you as “Hispanic American,” you also are probably aware that this label masks more than it reveals. As a third-

The Impact of Gender

Obviously, our culture’s values shape our development as males and females. Are you living in a society or at a time in history when men are encouraged to be househusbands and women to be corporate CEOs? The transgender liberation movement offers a compelling 21st century lesson that the “old model” that chromosomes are destiny doesn't fit the facts about human life. Still, throughout the world, females outlive males by at least two years (World Life Expectancy, 2011). And, as you will see throughout this book, our gender pathways are a bit different from birth through old age.

11

Are boys more aggressive than girls? When we see male/female differences in caregiving, career interests, and childhood play styles, are these differences mainly due to the environment (societal pressures or the way we are brought up) or to inborn, biological forces? Throughout this book, I’ll examine these questions as we explore the scientific truth of our gender stereotypes and spell out other fascinating facts about sex differences. To introduce this conversation, you might want to take the “Is It Males or Females?” quiz in Table 1.1. Keep a copy. As we travel through the lifespan, you can check the accuracy of your ideas.

|

|

|

Table 1.1 Belsky, Experiencing The Lifespan, 4e © 2016 Worth Publishers |

|

Now that you understand that our lifespan is a continuing work in progress that varies across cultures and historical times, let’s get to the science. After you complete this section’s Tying It All Together review quiz below, I will introduce the main theories, research methods, concepts, and scientific terms in this book.

Tying It All Together

Question 1.1

Imagine you were born in the eighteenth century. Which statement would be least true of your life?

You would have a good chance of dying during childhood.

You might be severely beaten by your parents.

You would start working right after high school.

You would not have an adolescence.

C. There was no real high school in the eighteenth century.

Question 1.2

Rosa is 80. Ramona is 65. In a sentence, describe the major statistical difference between these two women, and then label each person’s life stage.

Rosa is more likely to be physically disabled than Ramona. Rosa is old-

Question 1.3

Carlos was in his twenties during the 1980s; his grandfather reached adulthood in 1945. In comparing their lives, plug in the statistically correct items: Carlos was more/less likely to have divorced; Carlos entered the workforce at an older/younger age and got married later/earlier than his grandfather. Carlos had more/fewer years of education than his grandfather.

Carlos was more likely to have divorced, probably entered the workforce at an older age, and got married later than his grandfather. Carlos probably had more years of education than his grandpa.

Question 1.4

Pablo says, “I would never think of leaving my parents or living far from my brothers and sisters. A person must take care of his extended family before satisfying his own needs.” Peter says, “My primary commitment is to my wife and children. A person needs, above all, to make an independent life.” Pablo has a(n) ________ worldview, while Peter’s worldview is more ________.

collectivist; individualistic

Question 1.5

List and (possibly discuss with the class) the merits and downsides of Facebook.

Your answers here will all vary.