1.3 Theories: Lenses for Looking at the Lifespan

12

During her twenties, Jamila was probably searching for her identity. Susan’s sunny, people-

Theories attempt to explain what causes us to act as we do. They may allow us to predict the future. Ideally, they give us information about how to improve the quality of life. Theories in developmental science may offer broad explanations of behavior that apply to people at every age, or describe changes that occur at particular ages. This section provides a preview of both kinds of theories.

Let’s begin by outlining some theories (one is actually a research discipline) that offer general explanations of behavior. I’ve organized these theories somewhat chronologically—

Behaviorism: The Original Blockbuster “Nurture” Theory

Give me a dozen healthy infants … and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to be any specialist I might select—

(Watson, 1930, p. 104)

So proclaimed the early-

Exploring Reinforcement

According to Skinner, the general law of learning that causes each voluntary action, from forming our first words to mastering higher math, is operant conditioning. Responses that we reward, or reinforce, are learned. Responses that are not reinforced go away or are extinguished. So what accounts for Watson’s beggar men and thieves, the out-

One excellent place to see Skinner’s point is to take a trip to your local Walmart or restaurant. Notice how when children act up at the store parents often buy them a toy to quiet them down. At dinner, as long as a toddler is playing quietly, adults ignore her. When she starts to hurl objects off the table, they pick her up, kiss her, and take her outside. Then, they complain about their child’s difficult personality, not realizing that their own reinforcements have produced these responses!

13

One of Skinner’s most interesting concepts, derived from his work with pigeons, relates to variable reinforcement schedules. This is the type of reinforcement that typically occurs in daily life: We get reinforced unpredictably, so we keep responding, realizing that if we continue, at some point we will be reinforced. Readers with children will understand how difficult it is to follow the basic behavioral principle to be consistent or not let a negative variable schedule emerge. At Walmart, even though you vow, “I won’t give in to bad behavior!” as your toddler’s tantrums escalate, you cave in, simply to avoid other shoppers’ disapproving stares (“What an out-

Reinforcement (and its opposite process, extinction) is a powerful force for both good and bad. It explains why, if a child starts out succeeding early in elementary school (being reinforced by receiving A’s), he is apt to study more. If a kindergartner begins failing socially (does not get positive reinforcement from her peers), she is at risk for becoming incredibly shy or highly aggressive in third or fourth grade (see Chapter 6). If you were not being reinforced by people, wouldn’t you withdraw or act in socially inappropriate ways?

Behaviorism makes sense of why, after starting out loving, marriages can end in divorce. As newlyweds, couples are continually reinforcing each other with expressions of love. Then, over time, husbands and wives tend to ignore the good parts of their partner and pay attention when there is something wrong.

The theory even offers an optimistic environmental explanation for the physical and mental impairments of old age. If you were in a nursing home and weren’t being reinforced for remembering or walking, wouldn’t your memory or physical abilities decline? The key to producing well-

However, things are not that simple. Human beings do think and reason. People do not need to be personally reinforced to learn.

Taking a Different Perspective: Exploring Cognitions

Enter cognitive behaviorism (social learning theory), launched by Albert Bandura (1977; 1986) and his colleagues in the 1970s, in studies demonstrating the power of modeling, or learning by watching and imitating what other people do.

Because we are a social species, modeling (both imitating other people, and others reciprocally imitating us) is endemic in daily life. Given that we are always modeling everything from the latest hairstyle on, who are we most likely to generally model as children and adults?

Bandura (1986) finds that that we tend to model people who are nurturing, or relate to us in a caring way. (The good news here is that being a loving, hands-

Modeling similar people partly explains why, after children understand their gender label (girl or boy) at about age 2 1/2, they separate into sex-

14

Self-

Let’s imagine that your goal is to be a nurse, but you get an F on your first test in this course. If your academic self-

How do children develop low or high self-

By now, you may be impressed with behaviorism’s simple, action-

Still, many developmentalists, even people who believe that nurture (or the environment) is important, find behaviorism unsatisfying. Aren’t we more than just efficacy feelings or reinforced responses? Isn’t there a basic core to personality, and aren’t the lessons we learn in childhood vital in shaping adult life? Notice that behaviorism doesn’t address that core question: What really motivates us as people? To address these gaps, developmental scientists, particularly in the past, turned to the insights of that world-

Psychoanalytic Theory: Focus on Early Childhood and Unconscious Motivations

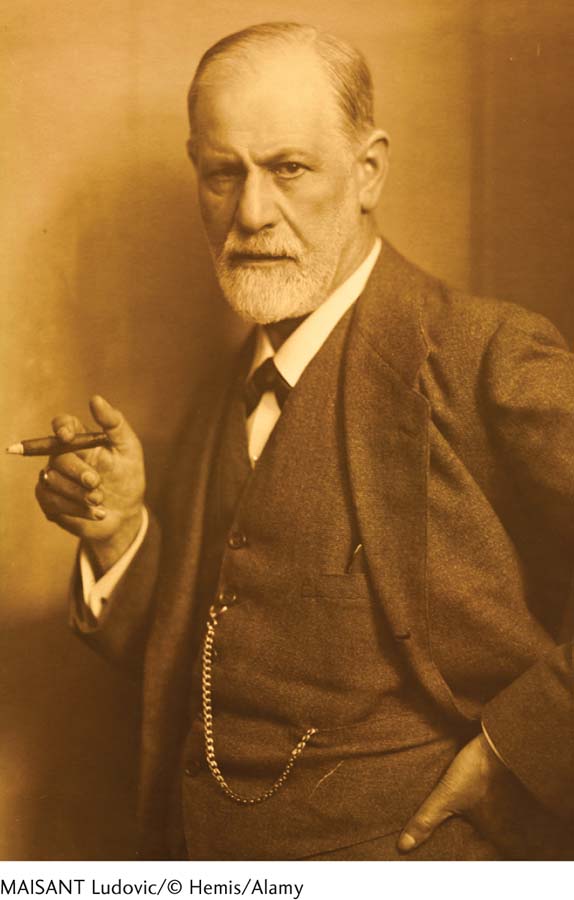

Freud’s ideas are currently not in vogue in developmental science. However, no one can dispute the fact that Sigmund Freud (1856–

Freud, a Viennese Jewish physician, wrote more than 40 books and monographs in a burst of brilliance during the early twentieth century. His ideas revolutionized everything from anthropology to the arts, in addition to jump-

Freud’s theory is called psychoanalytic because it analyzes the psyche or our inner life. By listening to his patients, Freud became convinced that our actions are dominated by feelings of which we are not aware. The roots of emotional problems lay in repressed (made unconscious) feelings from early childhood. Moreover, “mothering,” during the first five years of life, determines adult mental health.

Specifically, Freud posited three hypothetical structures. The id, present at birth, is the mass of instincts, needs, and feelings we have when we arrive in the world. During early childhood, the conscious, rational part of our personality—

15

According to Freud and his followers, if our parents are excellent caregivers, we will develop a strong ego, which sets us up to master the challenges of life. If they are insensitive or their caregiving is impaired, our behavior will be id driven, and our lives will be out of control. The purpose of his therapy, called psychoanalysis, was to enable his patients to become aware of the repressed early childhood experiences causing their symptoms and liberate them from the tyranny of the unconscious to live rational, productive lives. (As Freud famously put it, where id there was, ego there will be.)

In sum, according to Freud: (1) Human beings are basically irrational; (2) lifelong mental health depends on our parents’ caregiving during early life; and (3) self-

By now many of you might be on a similar page as Freud. Where you are apt to part serious company with the theory relates to Freud’s stages of sexuality. Freud argued that sexual feelings (which he called libido) are the motivation driving human life, and he put forth the shocking idea—

Partly because his sexual stages seem so foreign to our thinking, we tend to reject psychoanalytic theory as outdated—

Attachment Theory: Focus on Nurture, Nature, and Love

British psychiatrist John Bowlby formulated attachment theory during the mid-

In observing young children separated from their mothers, Bowlby noticed that babies need to be physically close to a caregiver during the time when they are beginning to walk (Bowlby, 1969, 1973; Karen, 1998). Disruptions in this biologically programmed attachment response, he argued, if prolonged, might cause serious problems later in life. Moreover, our impulse to be close to a “significant other” is a basic human need during every stage of life.

How does the attachment response develop? Are Bowlby and Freud right that our early attachments determine adult mental health? How can we draw on attachment theory to understand everything from adult love relationships to our concerns as we approach death? Stay tuned for answers as we explore this influential theory throughout this book.

16

Why did Bowlby’s ideas eclipse psychoanalytic theory? A main reason was that Bowlby agreed with a late-

Evolutionary Psychology: Theorizing About the “Nature” of Human Similarities

Evolutionary psychologists are the mirror image of behaviorists. They look to nature, or inborn biological forces that have evolved to promote survival, to explain how we behave. Why do pregnant women develop morning sickness just as the fetal organs are being formed, and why do newborns prefer to look at attractive faces rather than ugly ones? (That’s actually true!) According to evolutionary psychologists, these reactions cannot be changed by modifying the reinforcers. They are based in the human genetic code that we all share.

Evolutionary psychology lacks the practical, action-

Behavioral Genetics: Scientifically Exploring the “Nature” of Human Differences

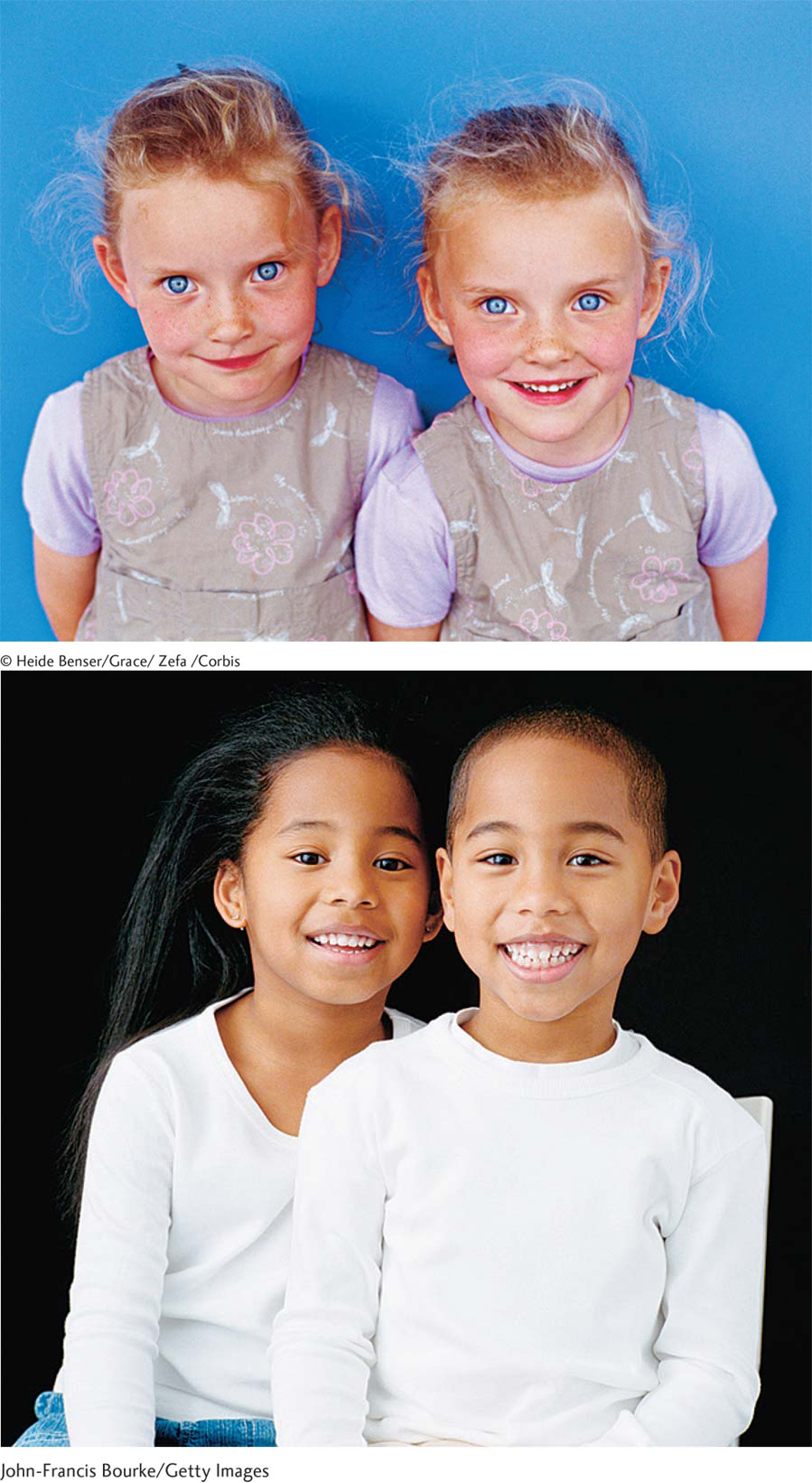

Behavioral genetics is the name for research strategies devoted to examining the genetic contribution to the differences we see between human beings. How genetic is the tendency to bite our nails, develop bipolar disorders, have specific attitudes about life? To answer these kinds of questions, scientists typically use twin and adoption studies.

17

In twin studies, researchers typically compare identical (monozygotic) twins and fraternal (dizygotic) twins on the trait they are interested in (playing the oboe, obesity, and so on). Identical twins develop from the same fertilized egg (it splits soon after the one-

For instance, to conduct a twin study to determine the heritability of friendliness, you would select a large group of identical and fraternal twins. You would give both sets of twins tests measuring outgoing attitudes, and then compare the strength of the relationships you found for each twin group. Let’s say the identical twins’ scores were incredibly similar—

In adoption studies, researchers compare adopted children with their biological and adoptive parents. Here, too, they evaluate the impact of heredity on a trait by looking at how closely these children resemble their birth parents (with whom they share only genes) and their adoptive parents (with whom they share only environments).

Twin studies of children growing up in the same family and adoption studies are fairly easy to carry out. The most powerful evidence for genetics comes from the rare twin/adoption studies, in which identical twins are separated in childhood and reunited in adult life. If Joe and James, who have exactly the same DNA, have similar abilities, traits, and personalities, even though they grow up in different families, this would be strong evidence that genetics plays a crucial role in who we are.

Consider, for instance, the Swedish Twin/Adoption Study of Aging. Researchers combed national registries to find identical and fraternal twins adopted into different families in that country—

While specific qualities varied in their heritabilities, you might be surprised to know that the most genetically determined quality was IQ (Pedersen, 1996). In fact, if one twin took the standard intelligence test, statistically speaking we could predict that the other twin would have an almost identical IQ despite living apart for almost an entire lifetime!

Behavioral genetic studies such as these have opened our eyes to the role of nature in shaping who we are (Turkheimer, 2004). Our tendencies to be religious, vote for conservative Republicans (Bouchard and others, 2004), drink to excess (Agrawal & Lynskey, 2008), or get divorced—

These studies have given us tantalizing insights into nurture too. It’s tempting to assume that children growing up in the same family share the same nurture, or environment. But as you can see in the How Do We Know research box on page 18, that assumption is wrong. We inhabit different life spaces than our brothers and sisters, even when we eat at the same dinner table and share the same room—

18

HOW DO WE KNOW…

that our nature affects our upbringing?

For much of the twentieth century, developmentalists assumed that parents treated all of their children the same way. We could classify mothers as either nurturing or rejecting, caring or cold. The Swedish Twin/Adoption Study turned these basic parenting assumptions upside down (Plomin & Bergeman, 1991).

Researchers asked middle-

What was happening? The answer, the researchers concluded, was that the genetic similarities in the twins’ personalities created similar family environments. If Joe and Jim were both easy, kind, and caring, they evoked more loving parenting. If they were temperamentally difficult, they caused their adoptive parents to react in more rejecting, less nurturant ways.

I vividly saw this evocative, child-

And now, the plot thickens. When I met Thomas’s biological mother, I found out that she also has dyslexia. She’s energetic and peppy. It’s one thing to see the impact of nature in my son, as his mother revealed. But I can’t help wondering…. Maureen is a very different person than I am (although we have a terrific time together—

The bottom line is that there is no such thing as nature or nurture. To understand human development, scientists need to explore how nature and nurture combine.

Nature and Nurture Combine: Where We Are Today

Let’s now lay out two basic nature-

Principle One: Our Nature (Genetic Tendencies) Shapes Our Nurture (Life Experiences)

Developmentalists understand that nature and nurture are not independent entities. Our genetic tendencies shape our wider-

Evocative forces refer to the fact that our inborn talents and temperamental tendencies evoke, or produce, certain responses from the world. A joyous child elicits smiles from everyone. A child who is temperamentally irritable, hard to handle, or has trouble sitting still is unfortunately set up to get the kind of harsh parenting she least needs to succeed. Human relationships are bidirectional. Just as you get grumpy when with a grumpy person, fight with your difficult neighbor, or shy away from your colleague who is paralyzingly shy, who we are as people causes other people to react to us in specific ways, driving our development for the good and the bad.

Active forces refer to the fact that we actively select our environments based on our genetic tendencies. A child who is talented at reading gravitates toward devouring books and so becomes a better reader over time. His brother, who is well coordinated, may play baseball three hours a day and become a star athlete in his teenage years. Because we choose activities to fit our biologically based interests and skills, what start out as minor differences between people in early childhood snowball—

Principle 2: We Need the Right Nurture (Life Experiences) to Fully Express Our Nature (Genetic Talents)

19

Developmentalists understand that even if a quality is mainly genetic, its expression can be 100 percent dependent on the outside world. Let’s illustrate by returning to the high heritabilities for intelligence. If you lived in an impoverished developing country, were malnourished, and worked as a laborer in a field, having a genius-

The most fascinating example that a high-

What is causing this upward shift? Obviously, our “genetic,” intellectual capacities can’t have changed. It’s just that as human beings have become better nourished, more educated, and more technologically adept, they perform better, especially on the kinds of abstract-

My discussion brings home the fact that to promote our human potential, we need to provide the best possible environment. This is why a core goal of developmental science is to foster the correct person–

Hot in Developmental Science: Environment-Sensitive Genes and Epigenetically Programmed Pathways

It’s a no brainer that we need to provide a superior environment for every child (and adult). But why does one child sail through traumas, such as poor parenting, while another breaks down under the smallest stress? What causes that same “genetically fragile” boy or girl to excel in a nurturing setting, such as high-

20

Epigenetics refers to the study of how our environment—

Emphasis on Age-

Now that I’ve highlighted this book’s basic nature combines with nurture message, it’s time to explore the ideas of two psychologists who view human development as occurring in defined stages. Let’s start with Erik Erikson.

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Tasks

Erikson, born in Germany in 1904, was an analyst who, like Bowlby, adhered to most tenets of psychoanalytic theory; but rather than emphasizing sexuality, Erikson (1963) saw becoming an independent self and relating to others as our basic motivations (which explains why Erikson’s theory is called psychosocial to distinguish it from Freud’s psychosexual stages). Erikson, however, is often labeled the father of lifespan development because, unlike Freud, he believed development occurs throughout life. He spelled out unique challenges we face at each life stage.

You can see these psychosocial tasks, or challenges, listed in Table 1.2. Each task, Erikson argued, builds on another because we cannot master the issue of a later stage unless we have accomplished the developmental milestones of the previous ones.

| Life Stage | Primary Task |

|---|---|

| Infancy (birth to 1 year) | Basic trust versus mistrust |

| Toddlerhood (1 to 2 years) | Autonomy versus shame and doubt |

| Early childhood (3 to 6 years) | Initiative versus guilt |

| Middle childhood (6 years to puberty) | Industry versus inferiority |

| Adolescence (teens into twenties) | Identity versus role confusion |

| Young adulthood (twenties to early forties) | Intimacy versus isolation |

| Middle adulthood (forties to sixties) | Generativity versus stagnation |

| Late adulthood (late sixties and beyond) | Integrity versus despair |

|

Table 1.2 Belsky, Experiencing The Lifespan, 4e © 2016 Worth Publishers |

|

Notice how parents take incredible joy in satisfying their baby’s needs and you will understand why Erikson believed that basic trust (the belief that the human world is caring) is our fundamental life task in the first year of life. Erikson’s second psychosocial task, autonomy, makes sense of the infamous “no stage” and “terrible twos.” It tells us that we need to celebrate this not-

How have developmentalists expanded on Erikson’s ideas about identity? Is Erikson right that nurturing the next generation, or generativity, is the key to a fulfilling adult life? These are just two questions I’ll be addressing as we draw on Erikson’s theory to help us think more deeply about the challenges we face at each life stage.

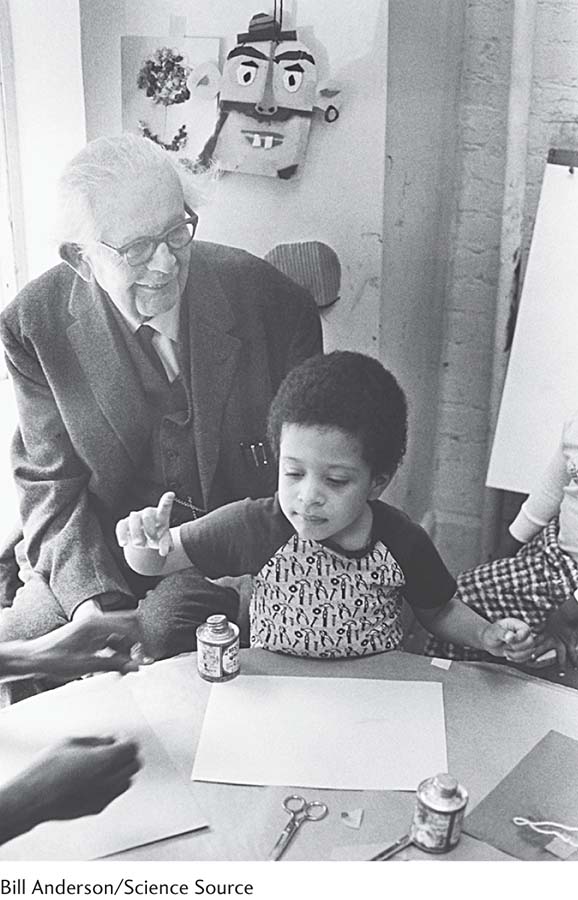

Erikson offered a general emotional roadmap for our developing lives. But—

Piaget’s Cognitive Developmental Theory

21

A 3-

Piaget, born in 1894 in Switzerland, was a child prodigy himself. As the teenaged author of several dozen articles on mollusks, he was already becoming well known in that field (Flavell, 1963; Wadsworth, 1996). Piaget’s interests shifted to studying children when he worked in the laboratory of a psychologist named Binet, who was devising the original intelligence test. Rather than ranking children according to how much they knew, Piaget became fascinated by children’s incorrect responses. He spent the next 60 years meticulously devising tasks to map the minds of these mysterious creatures in our midst.

Piaget believed—

| Age | Name of Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0– |

Sensorimotor | The baby manipulates objects to pin down the basics of physical reality. This stage, ending with the development of language, will be described in Chapter 3. |

| 2– |

Preoperations | Children’s perceptions are captured by their immediate appearances. “What they see is what is real.” They believe, among other things, that inanimate objects are really alive and that if the appearance of a quantity of liquid changes (for instance, if it is poured from a short, wide glass into a tall, thin one), the amount actually becomes different. You will learn about all of these perceptions in Chapter 5. |

| 8– |

Concrete operations | Children have a realistic understanding of the world. Their thinking is really on the same wavelength as adults’. While they can reason conceptually about concrete objects, however, they cannot think abstractly in a scientific way. |

| 12+ | Formal operations | Reasoning is at its pinnacle: hypothetical, scientific, flexible, fully adult. The person’s full cognitive human potential has been reached. We will explore this stage in Chapter 9. |

|

Table 1.3 Belsky, Experiencing The Lifespan, 4e © 2016 Worth Publishers |

||

Let’s illustrate by reflecting on your own thinking while you were reading the previous section. Before reading this chapter, you probably had certain ideas about heredity and environment. In Piaget’s terminology, let’s call them your “heredity/environment schemas.” Perhaps you felt that if a trait is highly genetic, changing the environment doesn’t matter; or you may have believed that genetics and environment were totally separate. While fitting (assimilating) your reading into these existing ideas, you entered a state of disequilibrium—

22

Piaget was a great advocate of hands-

By now, you may be overwhelmed by theories and terms. But take heart. You have the basic concepts you need for understanding this semester well in hand! Now, let’s conclude by exploring a worldview that says, “Let’s embrace all of these influences on development and explore how they interact.” (For a summary of the theories, see Table 1.4.)

| Nature vs. Nurture Emphasis and Ages of Interest | Representative Questions | |

|---|---|---|

| Behaviorism | Nurture (all ages) | What reinforcers are shaping this behavior? Who is this person modeling? How can I stimulate self- |

| Psychoanalytic theory | Nurture | What unconscious motives, stemming from early childhood, are motivating this person? |

| Attachment theory | Nature and nurture (infancy but also all ages) | How does the attachment response unfold in infancy? What conditions evoke this biologically programmed response at every life stage? |

| Evolutionary theory | Nature (all ages) | How might this behavior be built into the human genetic code? |

| Behavioral genetics | Nature (all ages) | To what degree are the differences I see in people due to genetics? |

| Erikson’s theory | (all ages) | Is this baby experiencing basic trust? Where is this teenager in terms of identity? Has this middle- |

| Piaget’s theory | Children | How does this child understand the world? What is his thinking like? |

|

Table 1.4 Belsky, Experiencing The Lifespan, 4e © 2016 Worth Publishers |

||

The Developmental Systems Perspective

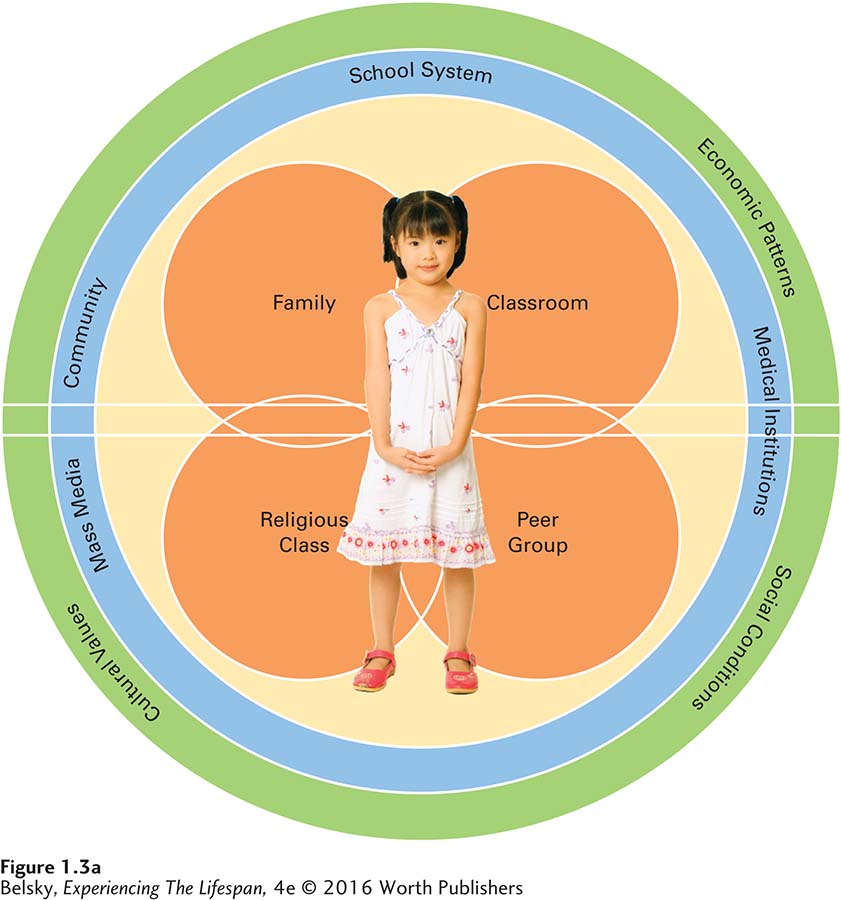

An influential child psychologist named Urie Bronfenbrenner (1977) was among the earliest lifespan theorists to highlight the principle that real-

23

Developmental systems theorists stress the need to use many different approaches. There are many valid ways of looking at behavior. Our actions do have many causes. To fully understand development, we need to draw on the principles of behaviorism, attachment theory, evolutionary psychology, and Piaget. At the widest societal level, to explain our actions, we need to look outward to our culture and cohort. At the molecular level, we need to look inward to our genes. We have to embrace the input of everyone, from nurses to neuroscientists from anthropologists to molecular biologists, to make sense of each individual life.

Developmental systems theorists emphasize the need to look at how processes interact. Bronfenbrenner pointed out that our genetic tendencies influence the cultures we construct; the cultures we live in affect the expression of our genes. In the same way that our body systems and processes are in constant communication, continual back-

and- forth influences are what human development is all about (see Diamond, 2009).

24

For example, let’s consider that basic marker: poverty. Growing up in poverty might affect your attachment relationships. You are less likely to get attention from your parents because they are under stress. You might not get adequate nutrition. Your neighborhood could be a frightening place. Each stress might overload your body, activating negative genetic tendencies and setting you up physiologically for emotional problems down the road.

But some children, because of their genetics, their cultural background, or their cohort, might be insulated from the negative effects of growing up poor. Others might thrive. In a classic study tracing the lives of children growing up during the Great Depression, researchers discovered that if this event occurred at the right time in the life cycle (adolescence, when the young person could take action to help support the family), it produced an enduring sense of self-

Tying It All Together

Question 1.6

Ricardo, a third grader, is having trouble sitting still and paying attention in class, so Ricardo’s parents consult developmentalists about their son’s problem. Pick which comments might be made by: (1) a traditional behaviorist; (2) a cognitive behaviorist; (3) a Freudian theorist; (4) an evolutionary psychologist; (5) a behavioral geneticist; (6) an Eriksonian; (7) an advocate of developmental systems theory.

Ricardo has low academic self-

efficacy. Let’s improve his sense of competence at school. Ricardo, like other boys, is biologically programmed to run around. If the class had regular gym time, Ricardo’s ability to focus in class would improve.

Ricardo is being reinforced for this behavior by getting attention from the teacher and his classmates. Let’s reward appropriate classroom behavior.

Did you or your husband have trouble focusing in school? Perhaps your son’s difficulties are hereditary.

Ricardo’s behavior may have many causes, from genetics, to the reinforcers at school, to growing up in our twenty-

first- century Internet age. Let’s use a variety of different approaches to help him. Ricardo is having trouble mastering the developmental task of industry. How can we promote the ability to work that is so important at this age?

By refusing to pay attention in class, Ricardo may be unconsciously acting out his anger at the birth of his baby sister Heloise.

(1) c; (2) a; (3) g; (4) b; (5) d; (6) f ; (7) e

Question 1.7

In the above question, which suggestion involves providing the right person–

b. As Ricardo and other children need to run around, regular gym time would help to foster the best person–environment fit.

Question 1.8

Dr. Kaplan, a scientist, wants to determine how being born premature might alter our genetic propensity to develop chronic disease. The field Dr. Kaplan is working in is called (pick one): outergenetics/epigenetics.

Dr. Kaplan is working in a field called epigenetics.

Question 1.9

Billy, a 1-

assimilation; accommodation

Question 1.10

Samantha, a behaviorist, is arguing for her worldview, while Sally is pointing up behaviorism’s flaws. First, take Samantha’s position, arguing for the virtues of behaviorism, and then discuss some limitations of the theory.

Samantha might argue that behaviorism is an ideal approach to human development because it is simple, effective, and easy to carry out. Behaviorism’s easily mastered, action-