2.2 The First Step: Fertilization

Before embarking on this journey let’s focus on the starting point. What structures are involved in reproduction? What physiological process is involved in conceiving a child? What happens at the genetic level when a sperm and an egg unite to form a human being?

The Reproductive Systems

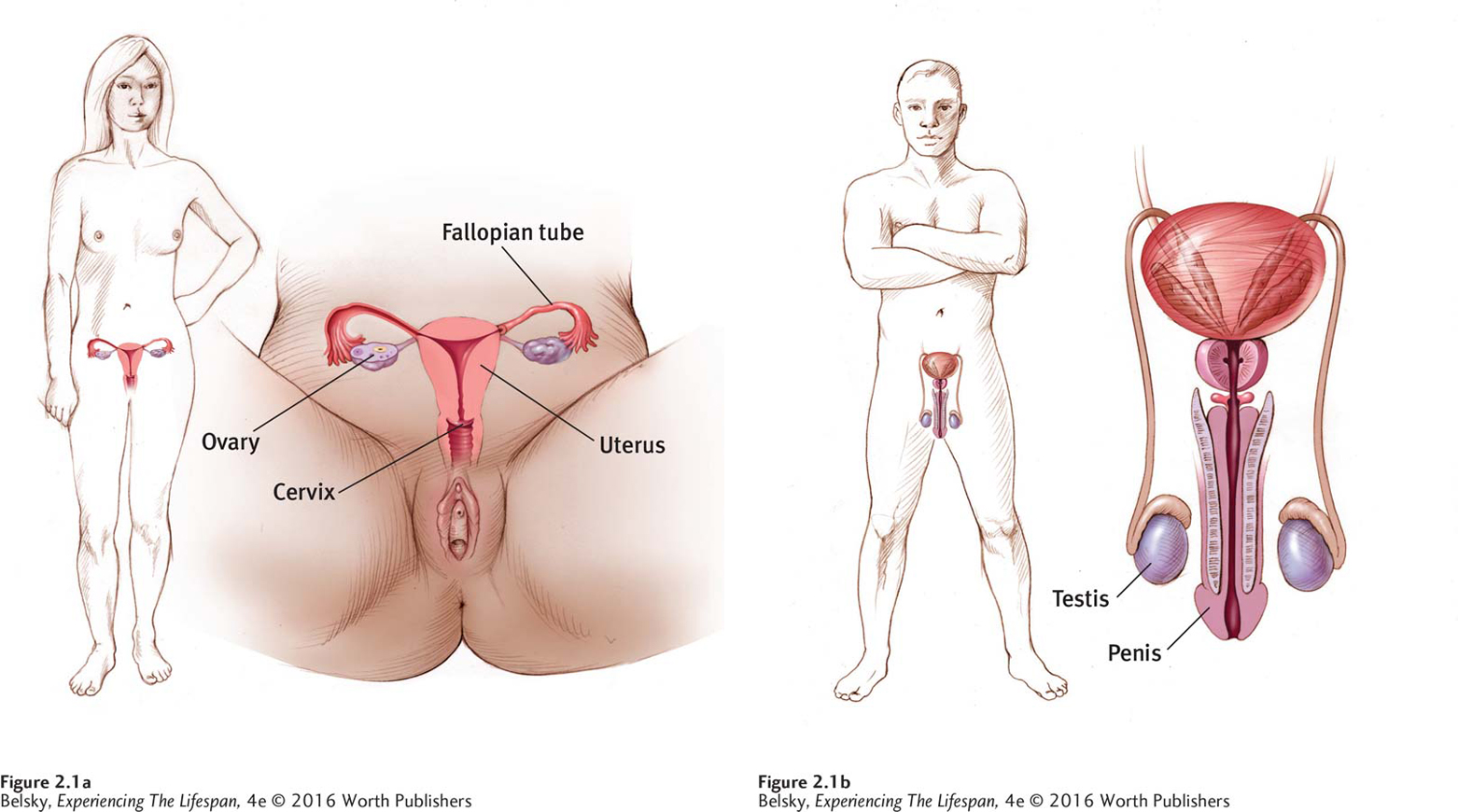

The female and male reproductive systems are shown in Figure 2.1a and Figure 2.1b. Notice that the female system has several basic parts:

Center stage is the uterus, the pear-

shaped muscular organ that carries the baby to term. The uterus is lined with a velvety tissue, the endometrium, which thickens in preparation for pregnancy and, if that event does not occur, sheds during menstruation. The lower section of the uterus is the cervix. During pregnancy, this thick uterine neck must perform an amazing feat: Be strong enough to resist the pressure of the expanding uterus; be flexible enough to open fully at birth.

Branching from the upper ends of the uterus are the fallopian tubes. These slim, pipelike structures serve as conduits to the uterus.

The feathery ends of the fallopian tubes surround the ovaries, the almond-

shaped organs where the ova, the mother’s egg cells, reside.

The Process of Fertilization

The pathway that results in fertilization—the union of sperm and egg—

At ovulation, a fallopian tube suctions the ovum in, and the tube begins vigorous contractions that propel the ovum on its three-

37

Now the male’s contribution to forming a new life arrives. In contrast to females, whose ova are all mainly formed at birth, the testes—male structures comparable to the ovaries—

To promote pregnancy, it’s best to have intercourse around ovulation. The ovum is receptive for about 24 hours while in the tube’s outer part. Sperm take a few hours to journey from the cervix to the tube. However, sperm can live almost a week in the uterus, which means that intercourse several days prior to ovulation may also result in fertilization (Marieb, 2004).

Although the ovum emits chemical signals as to its location, the tiny tadpole-

What happens now is a team assault. The sperm drill into the ovum, penetrating toward the center. Suddenly, one reaches the innermost part. Then the chemical composition of the ovum wall changes, shutting out the other sperm. The nuclei of the male and female cells move slowly together. When they meld into one cell, the landmark event called fertilization has occurred. What is happening genetically when the sperm and egg combine?

The Genetics of Fertilization

38

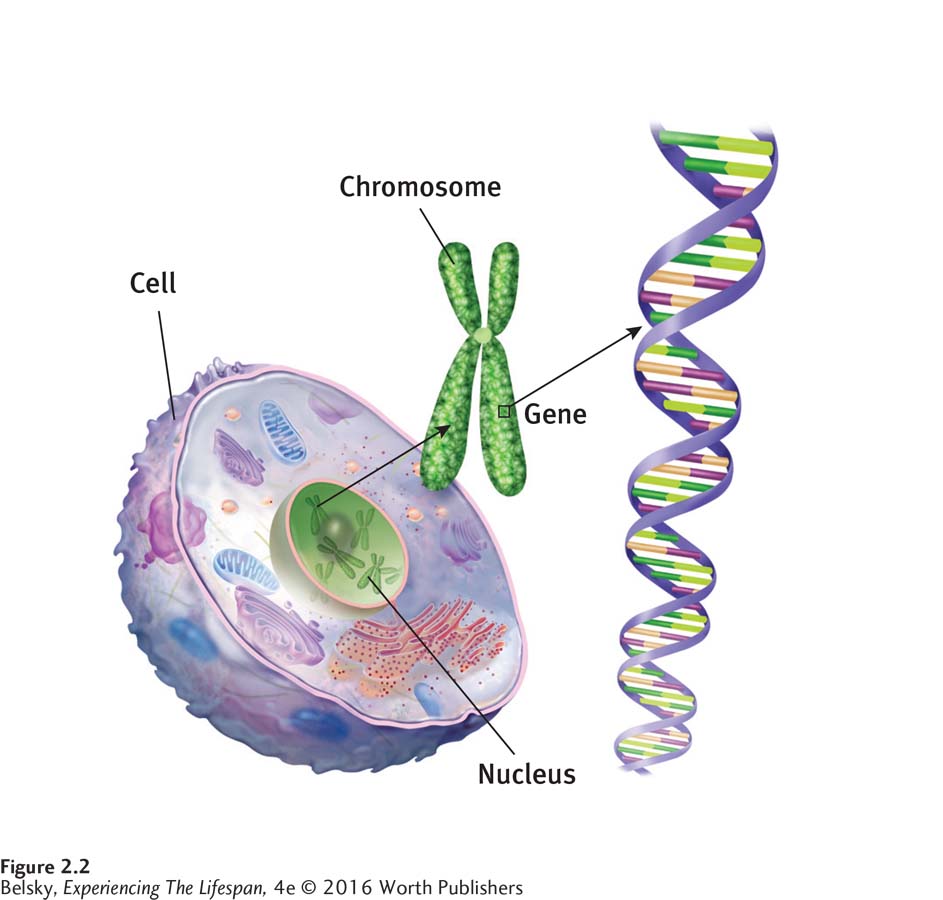

The answer lies in looking at chromosomes, ropy structures composed of ladder-

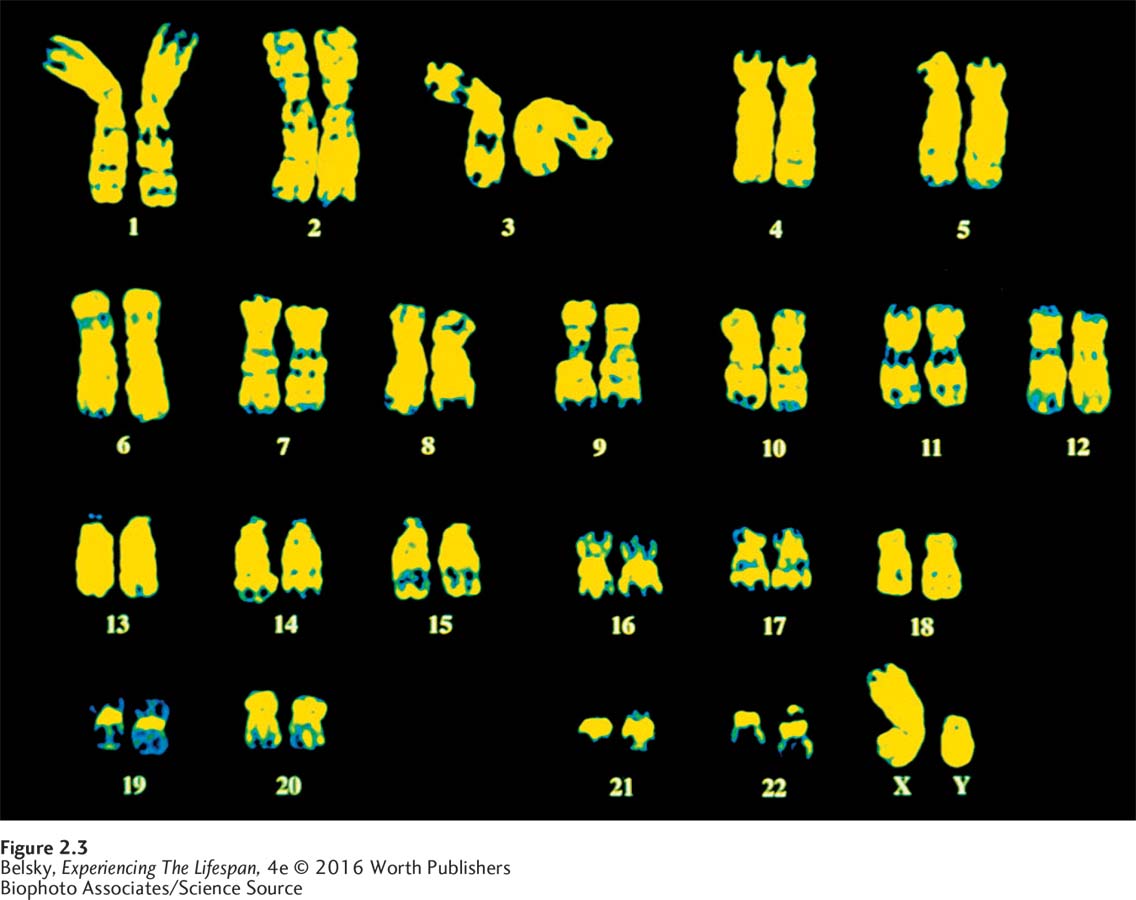

You can see the 46 paired male chromosomes in Figure 2.3. Notice that each chromosome pair (one from our mother and one from our father) is a match, except for the sex chromosomes. The X is longer and heavier than the Y. Because each ovum carries an X chromosome, our father’s contribution determines our sex. If a lighter, faster-

In the race to fertilization, the Y’s are statistically more successful; scientists estimate that 20 percent more male than female babies are conceived. But the prenatal period is particularly hard on males. If a family member learns that she is pregnant, the odds still favor her having a boy; but because more males die in the uterus, only 5 percent more boys than girls make it to birth (Werth & Tsiaras, 2002). And throughout life, males continue to be the less hardy sex, dying off at higher rates at every age. Recall from Chapter 1 that, throughout the developed world, women outlive men by at least two years.

Tying It All Together

39

Question 2.1

In order, list the structures involved in “getting pregnant.” Choose from the following: uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries. Then, name the structure in which fertilization occurs.

ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus; fertilization occurs in the fallopian tubes

Question 2.2

The __________ house the female’s genetic material, while the _________ contain the sperm. (Identify the correct names)

ovaries for female; testes for male

Question 2.3

Tiffany feels certain that if she has intercourse at the right time, she will get pregnant—

Tell Tiffany that the best time to have intercourse is around the time of ovulation, as fertilization typically occurs when the ovum is in the upper part of the fallopian tube.

Question 2.4

If a fetus has the XX chromosomal configuration he/she is more/less apt to survive the prenatal journey (and live longer) and is more/less apt to be conceived.

she is more apt to survive and less apt to be conceived.