2.4 Pregnancy

The 266-

Pregnancy differs, however, from the universally patterned process of prenatal development. Despite having classic symptoms, here individual differences are the norm.

Scanning the Trimesters

With the strong caution that the following symptoms vary—

First Trimester: Often Feeling Tired and Ill

43

After the blastocyst implants in the uterus—

Hormones trigger these symptoms. After implantation, the production of progesterone (literally pro, or “for,” gestation)—the hormone responsible for maintaining the pregnancy—

Given this hormonal onslaught, the body changes, and the fact that the blood supply is being diverted to the uterus, the tiredness, dizziness, and headaches make sense. What about that other early pregnancy sign—

Morning sickness—

But morning sickness seems senseless: Doesn’t the embryo need all the nourishment it can get? Why, during the first months of pregnancy, might it be “good” to stop eating particular foods?

Consider these clues: The queasiness is at its height when the organs are forming, and, like magic, toward the end of the first trimester, usually (but not always) disappears. Munching on bread products helps. Strong odors make many women gag. Evolutionary psychologists theorize that, before refrigeration, morning sickness prevented the mother from eating spoiled meat or toxic plants, which could be especially dangerous during the embryo phase (Bjorklund & Pellegrini, 2002). If you have a friend struggling with morning sickness, you can give her this heartening information: Some research suggests that women with morning sickness are more likely to carry their babies to term.

This brings up that upsetting event: miscarriage. Roughly 1 in 10 pregnancies end in a first trimester fetal loss. For women in their late thirties, the chance of miscarrying during these weeks escalates to 1 in 5. Many miscarriages are inevitable—

Second Trimester: Feeling Much Better and Connecting Emotionally

Morning sickness, the other unpleasant symptoms, and the relatively high chance of miscarrying make the first trimester less than an unmitigated joy. During the second trimester, the magic kicks in.

By week 14, the uterus dramatically grows, often creating a need to shop for maternity clothes. The wider world may notice the woman’s expanding body: “Are you pregnant?” “How wonderful!” “Take my seat.” Around week 18, an event called quickening—a sensation like bubbles that signals the baby kicking in the womb—

Another landmark event that alters the emotional experience of pregnancy occurs at the beginning of the third trimester, when the woman can give birth to a living child. This important late-

Third Trimester: Getting Very Large and Waiting for Birth

44

Look at a pregnant woman struggling up the stairs and you’ll get a sense of her feelings during this final trimester: backaches (think of carrying a bowling ball); leg cramps; numbness and tingling as the uterus presses against the nerves of the lower limbs; heartburn, insomnia, and anxious anticipation as focus shifts to the birth (“When will this baby arrive?!”); uterine contractions occurring irregularly as the baby sinks into the birth canal and delivery draws very near.

Although women often do work up to the day of delivery, health-

Pregnancy Is Not a Solo Act

I don’t know what it’s like for you and your partner to hear the baby’s heartbeat, or see the ultrasound together, or feel the first kick. I lived through nine months of pregnancy alone. I thought this was supposed to be the happiest time of your life. I found myself losing weight instead of gaining and being depressed most of the time.

When I told my husband I was pregnant, he got furious, said he couldn’t afford the baby and moved out. So now what do I do—

As these quotations reveal, pregnancy has a different emotional flavor depending on the wider world. What forces turn this joyous time of life into nine months of distress?

One influence, as suggested above, lies in economic concerns. Studies routinely show that low socioeconomic status puts pregnant women at risk of feeling demoralized and depressed (see, for instance, Guardino & Schetter, 2014). Imagine coping with the stresses associated with being poor—

The main force, however, that predicts having a joyous pregnancy applies to both affluent and economically deprived women alike—

Does this mean going through pregnancy without a mate is a terrible thing? The answer is no. What matters is whether a woman feels generally cared about and loved (Abdou and others, 2010). Listen to this comment of an impoverished single woman whom researchers ranked as “thriving” during this time of life: “We’ve always been a close-

Suppose, like the woman quoted at beginning of this section, you were married, but your spouse was hostile to your pregnancy. Wouldn’t you rather be going through this journey with a loving family or good friends?

What About Dads?

45

This brings up the emotions of the standard pregnancy partner: dads. Given the attention we lavish on pregnant women, it should come as no surprise that fathers have been relatively ignored in the research exploring this transition of life. But fathers are also bonded to their babies-

Richard anguished,

I keep thinking that my wife is still pregnant. Where is my little girl? I was so ready to spoil her and treat her like a princess . . . but now she is gone. I don’t think I’ll ever be the same again.

(quoted in Jaffe & Diamond, 2011, p. 218)

And another grieving dad reported,

I had to be strong for Kate. I had to let her cry on me and then I would . . . drive up into the hills and cry to myself. I was trying to support her even though I felt my whole life had just caved in. . . .

(quoted in McCreight, 2004, p. 337)

As you saw in the quotation above, in coping with this trauma, men have a double burden. They may feel compelled to put aside their feelings to focus on their wives (Jaffe & Diamond, 2011; Rinehart & Kiselica, 2010). Plus, because the loss of a baby is typically seen as a “woman’s issue,” the wider world tends to marginalize their pain. These examples remind us that husbands are “pregnant” in spirit along with their wives. We should never thrust their feelings aside.

So, by returning to the beginning of the chapter, we now know that the cultural practice of pampering pregnant women makes excellent psychological sense—

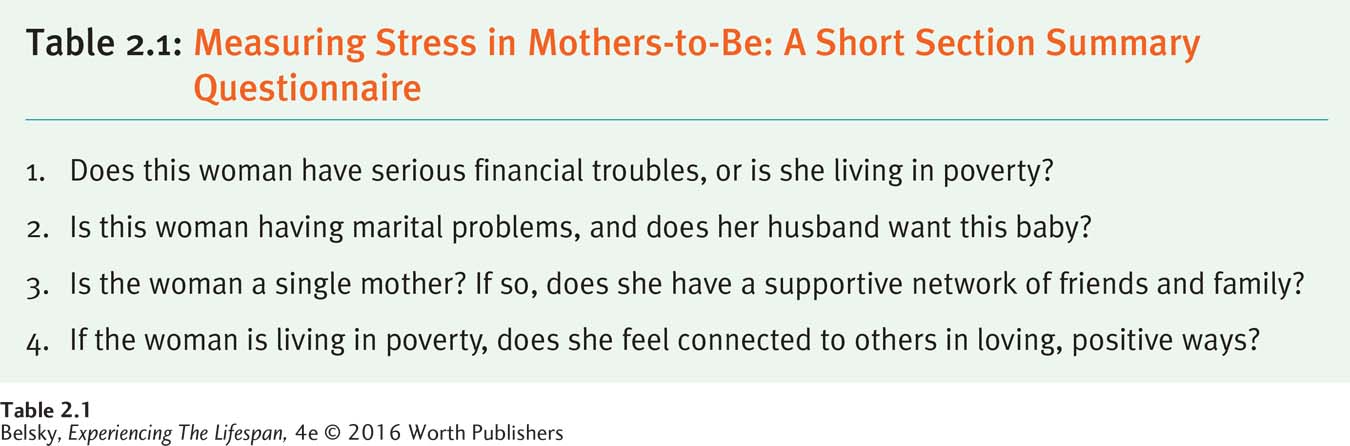

Table 2.1 summarizes these points in a brief “stress during pregnancy” questionnaire. Now, let’s return to the baby and tackle that common fear: “Will my child be healthy?”

Tying It All Together

Question 2.9

Samantha just entered her second trimester. Explain how she is likely to feel for the next few months. What symptoms was Samantha apt to describe during the first trimester, after learning she was pregnant?

In this second trimester, she will feel better physically and perhaps experience an intense sense of emotional connectedness when she feels the baby move. During the first trimester she may have been very tired, perhaps felt faint, and had morning sickness.

Question 2.10

You just learned your cousin is pregnant. What two forces might best predict her emotional state?

Does she feel as though she is supported and loved? Does she have economic problems?

Question 2.11

As a clinic director, you are concerned that men are often left out of the pregnancy experience. Design a few innovative interventions to make your clinic responsive to the needs of fathers-

You may come up with a host of interesting possibilities. Here are a few of mine: Include fathers in all pregnancy and birth educational materials the clinic provides; strongly encourage men to be present during prenatal exams; alert female patients about the need to be sensitive to their partners; set up a clinic-