Eating: The Basis of Living

Eating undergoes amazing changes during infancy. Let’s scan these transformations and then discuss nutritional topics that loom large in the first years of life.

Developmental Changes: From Newborn Reflexes to Two-Year-Olds’ Food Cautions

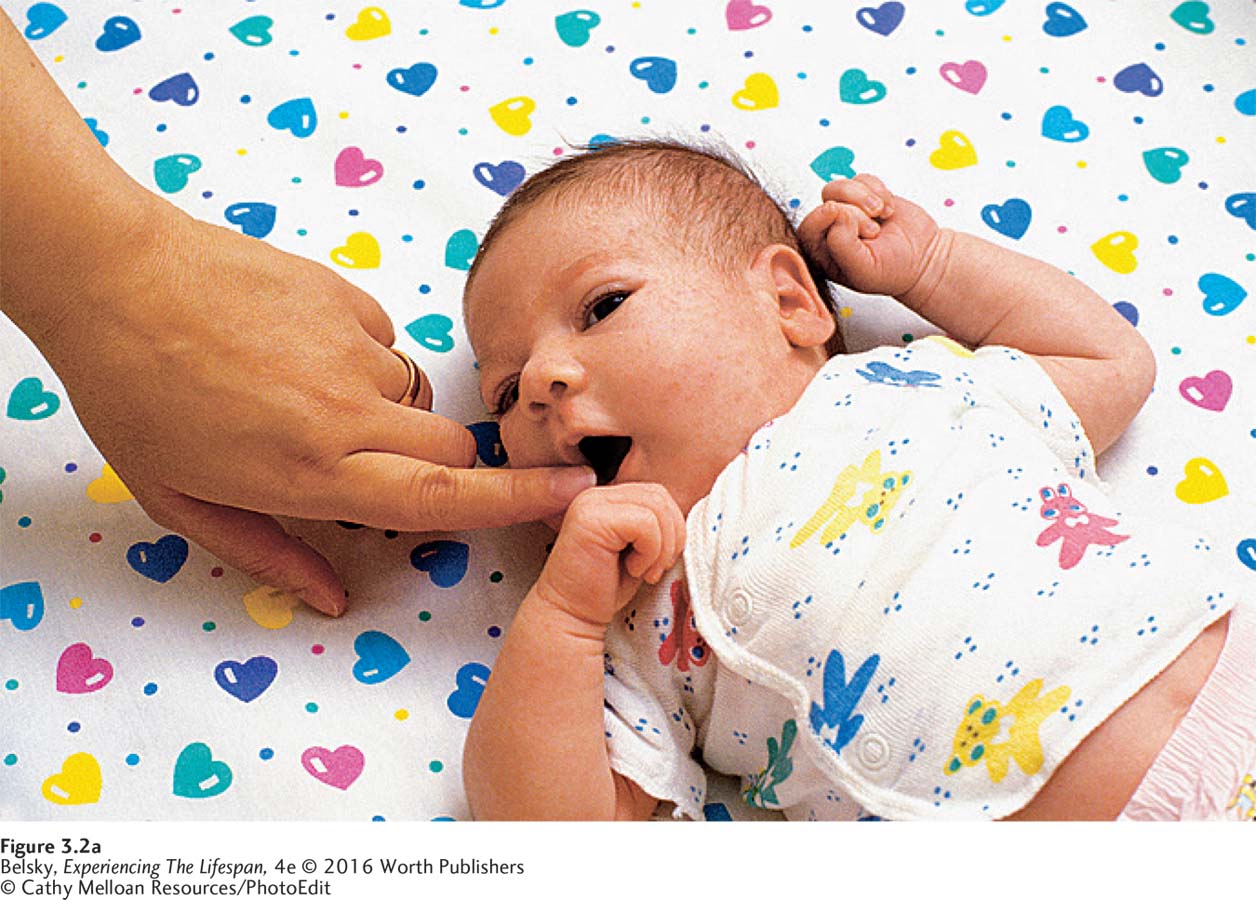

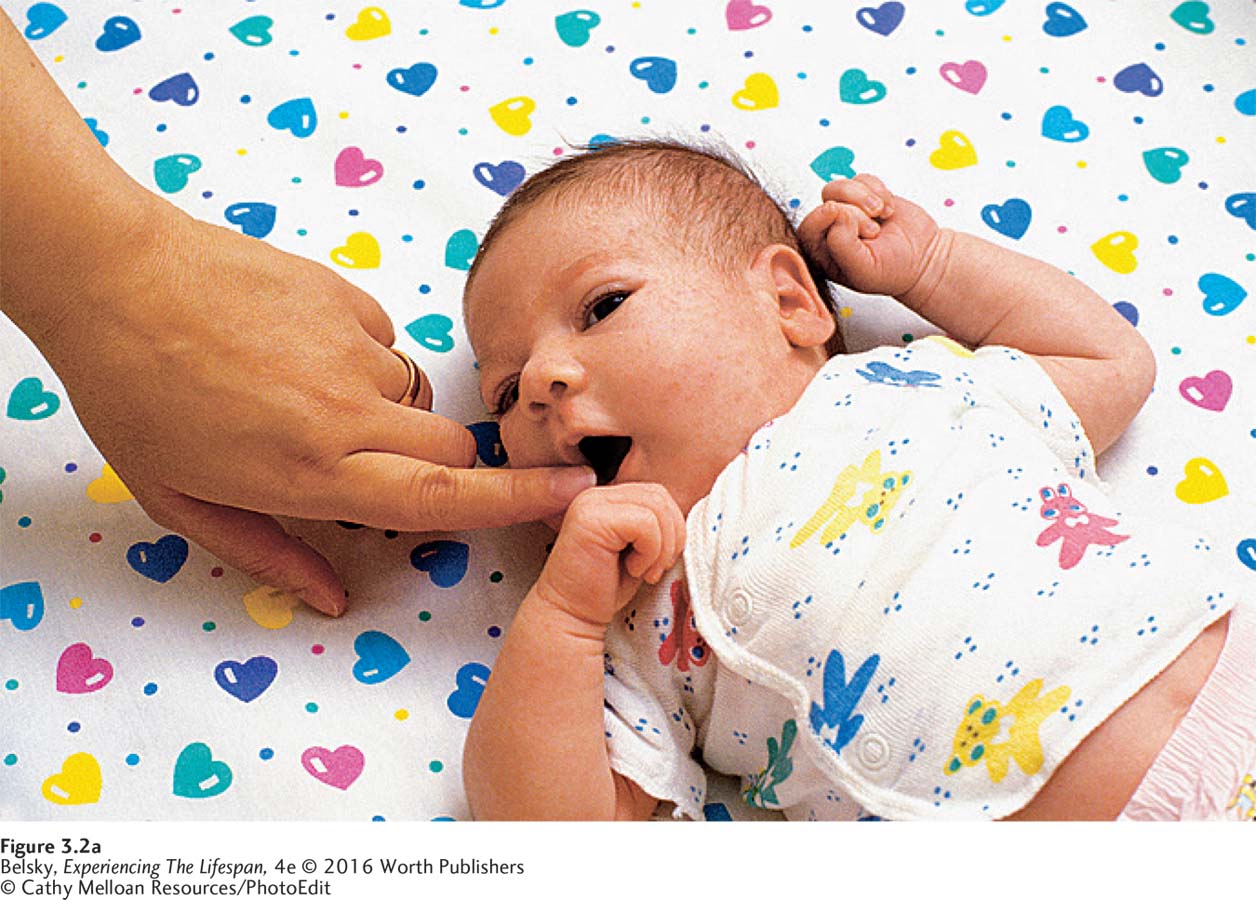

Newborns seem to be eating even when they are sleeping—a fact vividly brought home to me by the loud smacking that rhythmically erupted from my son’s bassinet. The reason is that babies are born with a powerful sucking reflex—they suck virtually all the time. Newborns also are born with a rooting reflex. If anything touches their cheek, they turn their head in that direction and suck.

Reflexes are automatic activities. Because they do not depend on the cortex, they are not under conscious control. It is easy to see why the sucking and rooting reflexes are vital to surviving after we exit the womb. If newborns had to learn to suck, they might starve before mastering that skill. Without the rooting reflex, babies would have trouble finding the breast.

Sucking and rooting have clear functions. What about the other infant reflexes shown in Figure 3.2c? Do you think the grasping reflex may have helped newborns survive during hunter-gatherer times? Can you think of why newborns, when stood on a table, take little steps (the stepping reflex)? Whatever their value, these reflexes, and a few others, must be present at birth. They must disappear as the cortex grows.

FIGURE 3.2a: Rooting: Whenever something touches their cheek, newborns turn their head in that direction and make sucking movements.

© Cathy Melloan Resources/PhotoEdit

FIGURE 3.2b: Sucking: Newborns are programmed to suck, especially when something enters their mouth.

Simon Fraser/Science Source

Figure 3.2: Grasping: Newborns automatically vigorously grasp anything that touches the palm of their hand.FIGURE 3.2a-c: Some newborn reflexes: If the baby’s brain is developing normally, each of these reflexes is present at birth and gradually disappears after the first few months of life. In addition to the reflexes illustrated here, other newborn reflexes include the Babinski reflex (stroke a baby’s foot and her toes turn outward), the stepping reflex (place a baby’s feet on a hard surface and she takes small steps), and the swimming reflex (if placed under water, newborns can hold their breath and make swimming motions).

As the cortex matures, voluntary processes replace these special newborn reflexes. By month four or five, babies no longer suck continually. Their sucking is governed by operant conditioning. When the breast draws near, they suck in anticipation of that delicious reinforcer: “Mealtime has arrived!” Still, Sigmund Freud named infancy the oral stage for good reason: During the first years of life, the theme is “Everything in the mouth.”

This impulse to taste everything leads to scary moments as children crawl and walk. There is nothing like the sickening sensation of seeing a baby put a forgotten pin in his mouth or taste your possibly poisonous plant. My personal heart-stopping experience occurred when my son was almost 2. I’ll never forget the frantic race to the emergency room after Thomas toddled in to joyously share a treasure, an open vial of pills!

Luckily, a mechanism may protect toddlers from sampling every potentially lethal substance during their first travels into the world. Between ages 1 1/2 and 2, children can revert to eating a few familiar foods, such as peanut butter sandwiches and apple juice. Evolutionary psychologists believe that, like morning sickness, this behavior is adaptive. Sticking to foods they know reduces the risk of children poisoning themselves when they begin to walk (Bjorklund & Pellegrini, 2002). Because this 2-year-old food caution gives caregivers headaches, we need to reassure frantic parents: Picky eating can be normal during the second year of life (as long as your child eats a reasonable amount of food).

What is the best diet during a baby’s first months? When is not having enough food a widespread problem? These questions bring up breast-feeding and global malnutrition.

Breast Milk: Nature’s First Food

During the late nineteenth century, U.S. babies faced perils after birth. A major threat was diarrhea, which caused a spike in infant mortality in the teeming city tenements. The newborns of immigrant Eastern European Jews, however, were less likely to develop diarrhea and other infectious diseases, because Jewish tradition dictated that mothers breast-feed their daughters and sons (Preston, 1991).

In the past, because it protected babies against impure milk, breast-feeding was a life-saving act. That choice has an impact today. Breast milk provides immunities to middle ear infections and gastrointestinal problems. It makes toddlers more resistant to colds and the flu (McNiel, Labbok, & Abrahams, 2010). Breast-fed babies show accelerated myelin formation (Deoni and others, 2013). They get higher scores on intelligence tests (Karns, 2001; Mortensen and others, 2002; Bernard, 2013). At age 1, they seem less physiologically reactive to stress (Beijers, Riksen-Walraven, & De Weerth, 2013).

Still, these findings involve correlations. And, as we know, just because there is a relationship between two variables does not mean one causes the other. The research exploring breast milk’s benefits rarely controls for that important “third variable”—social class. Caucasian women, who breast-feed for months, tend to be older, well educated, and affluent (Dennis and others, 2013). They spend more time in hands-on infant care (Smith & Ellwood, 2011). Women who nurse for months, one study showed, are less prone to becoming depressed as their baby travels into the stressful toddler years (Hahn-Holbrook and others, 2013). Is it really breast milk that promotes health, or the extra nurturing that goes along with providing this natural food?

As with pregnancy advice (recall Chapter 2), breast-feeding pronouncements have undergone fascinating historical shifts. During the l950s, doctors pushed formula as the “scientific” best food. Since research revealed nursing’s benefits, health care organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (2005) and UNICEF (2009) campaigned for exclusive breast-feeding during the first six months of life.

Contemporary women listened. Today, three out of four new U.S. mothers start out determined to breast-feed. But only a small percentage persists to the five- or six-month mark (Foss, 2010). Why?

Breast-feeding challenges

This breast-feeding mom is probably thrilled to provide her baby with the best first start; but, unfortunately, her choice might be more difficult than experts have led her to believe.

© Christina Kennedy/Alamy

One cause has to do with the need to work (Flower and others, 2008; Vaughn, 2010). Although U.S. employers must permit new mothers to pump their milk, imagine your problems following the six-month recommendation as a server or supermarket clerk who had to return to work soon after delivery (Guendelman and others, 2009). Women complain that breast-feeding is not practical. They are embarrassed to nurse their babies in public, especially if men are around (Vaaler and others, 2010; Vaughn, 2010).

Interesting nation-to-nation nursing-rate differences in the West reveal the impact that “other people” (in this case, society) make on breast-feeding. In Ireland, where people view formula as fine, most women bottle-feed soon after birth (Tarrant and others, 2013). In Canada and especially Norway, where breast-feeding is the only socially acceptable option, mothers try valiantly to nurse for the full six months (Andrews and Knaak, 2013).

This pressure to live up to the image of the ideal breast-feeding mom presents problems. Not only can nursing be inconvenient, but it can also be physically hard. As one U.S. mother reported: “I never realized . . . that I would be reduced to tears every time I fed” (Sheehan Schmied, & Barclay, 2013, p. 23). A Canadian woman, forced to abandon the breast, reported: “I felt so horrible . . . that I couldn’t do this for my child . . . You feel like less of a mother, less of a person (quoted in Andrews and Knaak, 2013, p. 95).

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that some Western moms are rebelling against breast-feeding “police” (Williams and others, 2013; Leeming and others, 2013; Regan and Ball, 2013). As Chloe, a U.S mother forced to give up the breast, rationalized: “I remember reading that . . . even just getting the first two weeks . . . is apparently really worthwhile . . . .” (quoted in Williams, Donaghue, & Kurz, 2013, p. 37). One British woman even took the step of viewing breast-feeding as narcissistic, when she argued, “I like . . . bottles because it gives her a chance to bond with my partner . . . and her grandma . . . .” (Leeming and others, 2013).

These quotes suggest we need to rethink the health-care message that automatically equates nursing with ideal motherhood. Many women (such as your author) cannot breast-feed. Millions of children (including your author) born during the mid-twentieth century, when bottle-feeding was standard, grew up to live successful lives. Rather than your milk delivery method, what’s really important is the way you love and bond with your child!

Malnutrition: A Serious Developing-World Concern

Breast-feeding allows every newborn a chance to thrive. However, there comes a time—at around 6 months of age—when babies need solid food. Then, the horrifying inequalities in global nutrition hit (Caulfield and others, 2006).

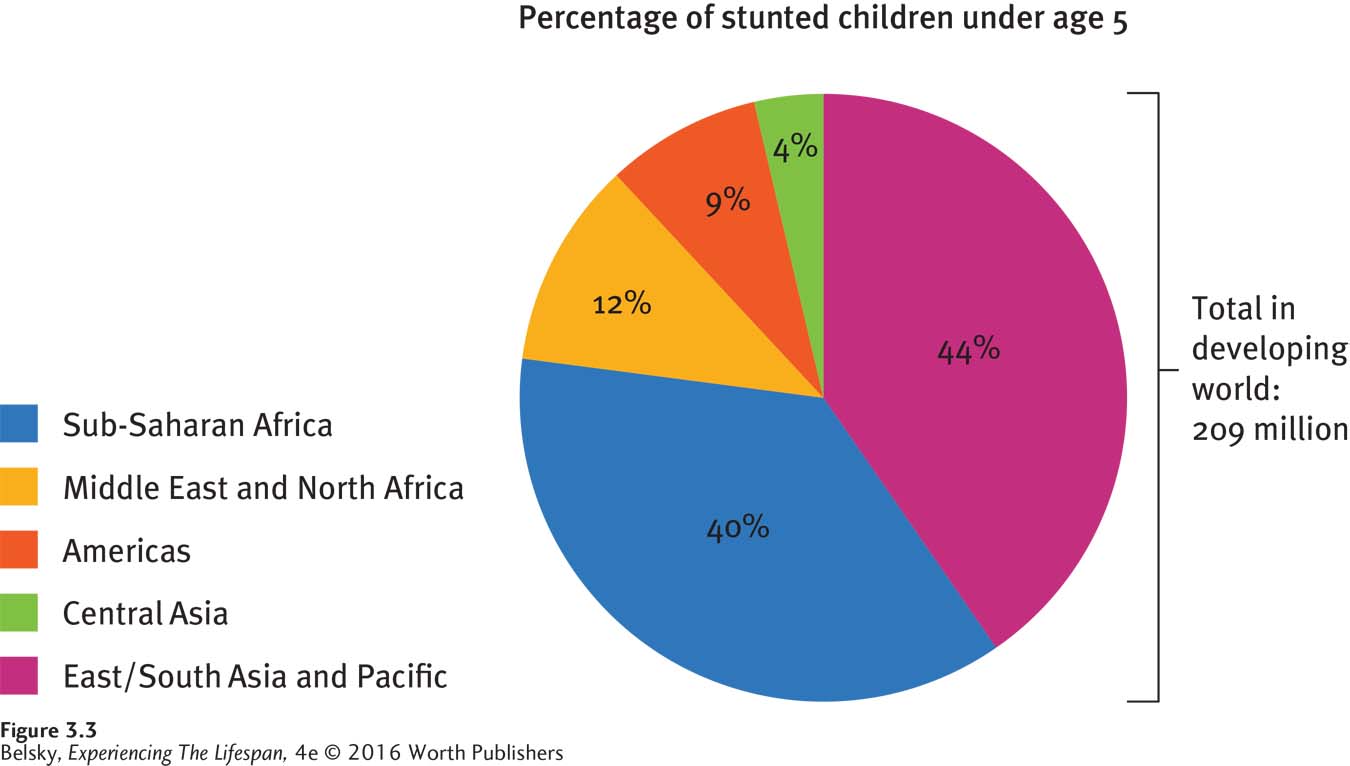

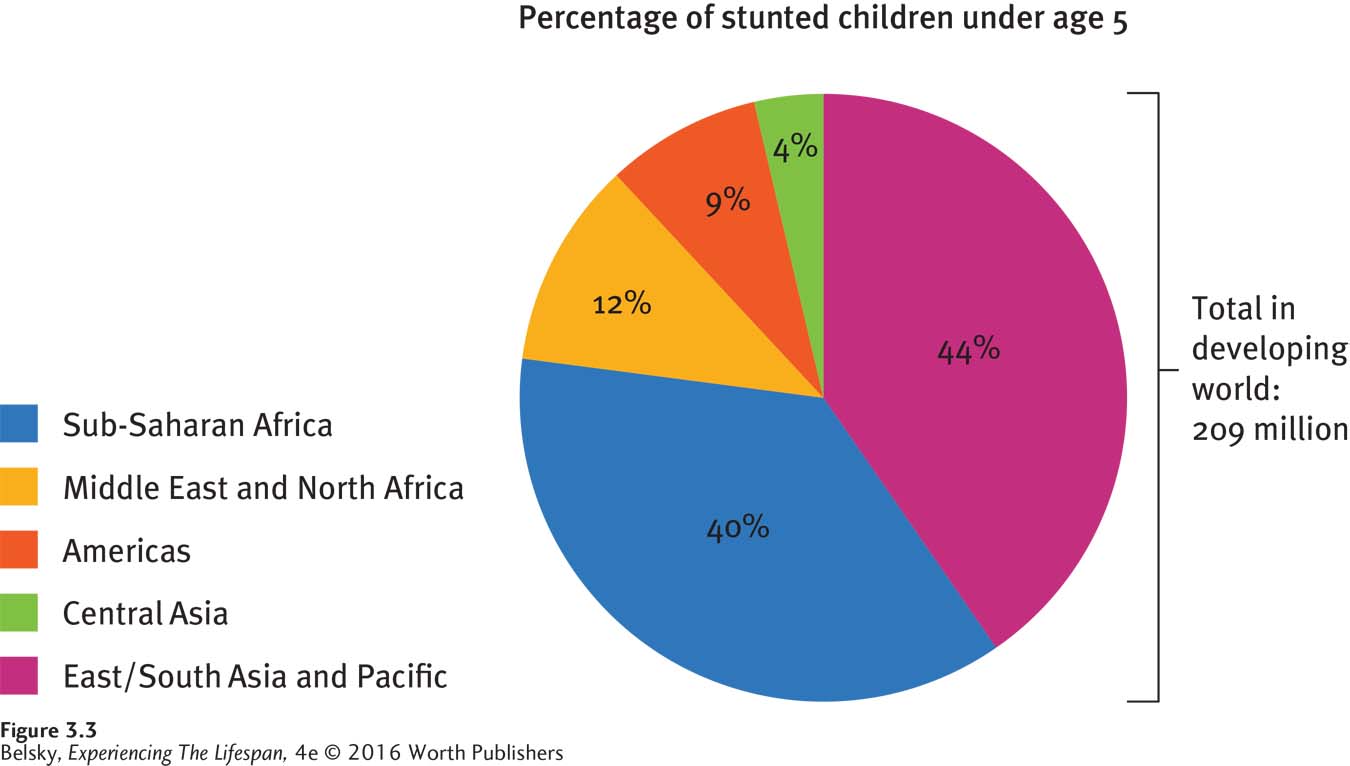

How many young children suffer from undernutrition, having a serious lack of adequate food? For answers, epidemiologists measure stunting, the percentage of children under age 5 who in a given region rank below the fifth percentile in height, according to the norms for their age. This very short stature is a symptom of chronic inadequate nutrition, which compromises every aspect of development and activity of life (Abubakar and others, 2010; UNICEF, 2009).

The good news is that in recent decades, stunting rates declined in poor regions of the world (UNICEF, 2002a). The tragedy, as Figure 3.3 shows, is that this sign of serious malnutrition still affects an alarming 209 million children, roughly two in five developing-world girls and boys (UNICEF, 2000). In Africa and South Asia, micronutrient deficiencies—inadequate levels of nutrients such as iron or zinc or Vitamin A—are rampant. Disorders, such as Kwashiorkor (described in the Experiencing the Lifespan box on page 80), can even strike when there is ample food.

Figure 3.3: Percentage of stunted children under age 5 in the developing world: This upsetting chart shows that stunting is common in much of the developed world—affecting many millions of young children, especially in East and South Asia and the Pacific regions and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Adapted from: UNICEF, 2000.

Experiencing the Lifespan: A Passion to Eradicate Malnutrition: A Career in Public Health

What is it like to battle malnutrition in the developing world? Listen to Richard Douglass describe his career:

I grew up on the South Side of Chicago—my radius was maybe 4 or 5 blocks in either direction. Then, I spent my junior year in college in Ethiopia, and it changed my life. I lived across the street from the hospital, and every morning I saw a flood of people standing in line. They would wait all day . . . , and eventually a cart would come and take away the dead. When I saw the lack of doctors, I realized I needed to get my Master’s and Ph.D. in public health.

In public health we focus on primary prevention, how to prevent diseases and save thousands of people from getting ill. My interest was in helping to eradicate Kwashiorkor in Ghana. What the name literally means is “the disease that happens when the second child is born.” The first child is taken off the breast too soon and given a porridge that doesn’t have amino acids, and so the musculature and the diaphragm break down. You get a bloated look (swollen stomach), and then you die. If a child does survive, he ends up stunted, and so looks maybe 5 years younger.

Once someone gets the disease, you can save their life. But it’s a 36-month rehabilitation that requires taking that child to the clinic for treatment every week. In Ghana it can mean traveling a dozen miles by foot. So a single mom with two or three kids is going to drop out of the program as soon as the child starts to look healthy. Because of male urban migration, the African family is in peril. If a family has a grandmother or great-auntie, the child can make it because this woman can take care of the children. So the presence of a grandma saves kids’ lives.

Most malnutrition shows up after wars. In Ghana there is tons of food. So it’s a problem of ignorance, not poverty. The issue is partly cultural. First, among some groups, the men eat, then women, then older children, then the babies get what is left. So the meat is gone, the fish is gone, and then you just have that porridge. We have been trying to impose a cultural norm that everyone sits around the dining table for meals, thereby ensuring that all the children get to eat. The other issue is just pure public health education—teaching families “just because your child looks fat doesn’t mean that he is healthy.”

I feel better on African soil than anywhere else. With poor people in the developing world who are used to being exploited, they are willing to write you off in a heartbeat if you give them a reason; but if you make a promise and follow through, then you are part of their lives. I keep going back to my college experience in Ethiopia . . . watching those people standing at the hospital, waiting to die. Making a difference for them is the reason why I was born.

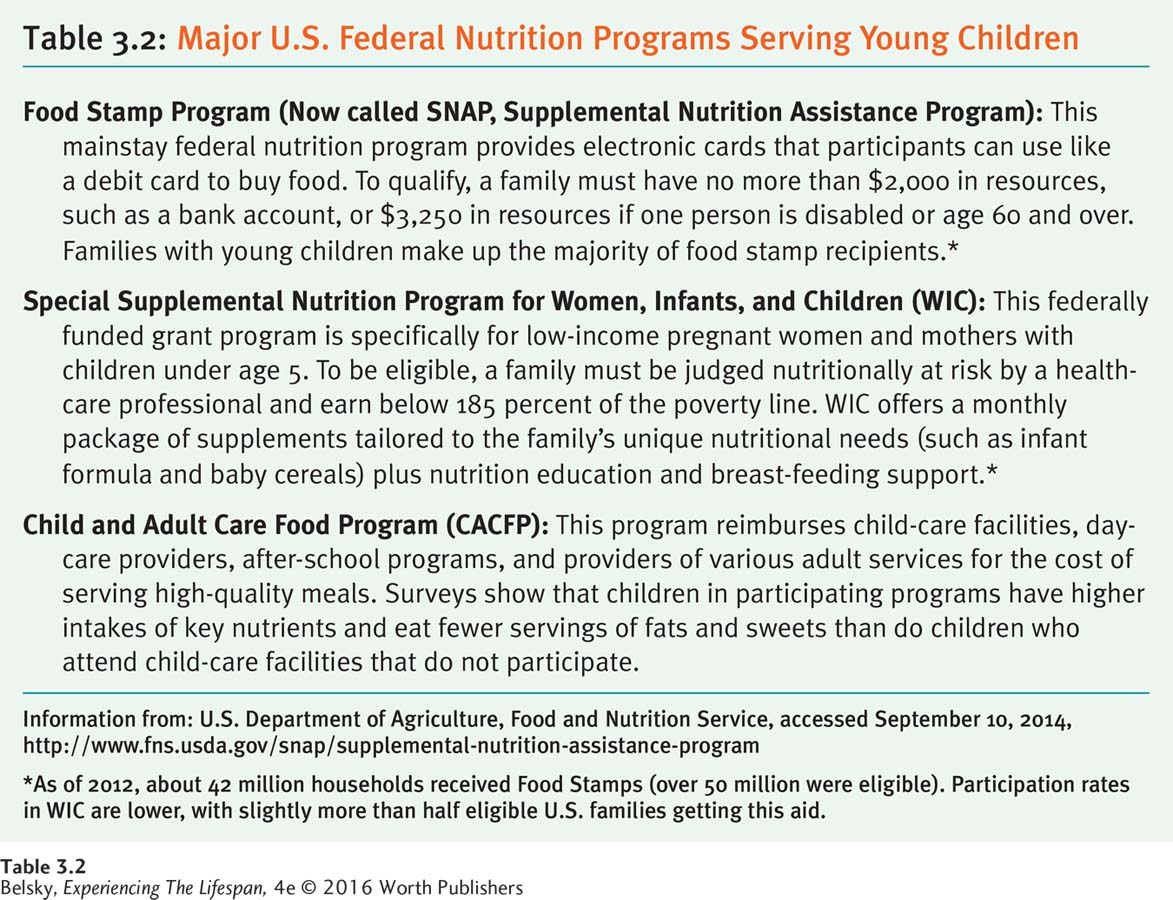

How many young children are stunted or chronically hungry in the United States? According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in 2012 roughly one in six U.S. households with children was designated as food insecure. This means that people reported sometimes not affording to provide a balanced diet, or being worried that their money for food might run out. About one in 20 families reported severe food insecurity. They sometimes went hungry due to lack of funds (Coleman-Jensen and others, 2013). However, because the United States provides nutrition-related entitlement programs described in Table 3.2, in our nation and other developed countries, poor children are spared the ongoing hunger that limits the life chances of so many boys and girls around the globe.

Crying: The First Communication Signal

At 2 months, when Jason cried, I was clueless. I picked him up, rocked him, and kept a pacifier glued to his mouth; I called my mother, the doctor, even my local pharmacist, for advice. Since it put Jason to sleep, my husband and I took car rides at three in the morning—the only people on the road were teenagers and other new parents like us. Now that my little love is 10 months old, I know why he is crying, and those lonely countryside tours are long gone.

Crying, that vital way we communicate our feelings, reaches its lifetime peak at around one month after birth (St. James-Roberts, 2007). However, a distinctive change in crying occurs at about month 4. As the cortex blossoms, crying rates decline, and babies use this communication to express their needs.

It’s tempting to think of crying as a negative state. However, because crying is as vital to survival as sucking, when babies cry too little, this can signal a neurological problem (Zeskind & Lester, 2001). When babies cry, we pick them up, rock them, and give them loving care. So, up to a certain point, crying helps cement the infant–parent bond.

Still, there is a limit. When a baby cries continually, she may have that bane of early infancy—colic. Despite what some “friends” (unhelpfully) tell new mothers, it’s a myth that inept parents produce colicky babies. Colic is caused by an immature nervous system. After they exit the cozy womb, some babies get unusually distressed when bombarded by stimuli, such as being handled or fed (St. James-Roberts, 2007). So, we need to back off from blaming stressed-out moms and dads for this biological problem of early infant life.

The good news is that colic is short-lived. Most parents find that around month 4, their baby suddenly becomes a new, pleasant person overnight. For this reason, there is only cause for concern when a baby cries excessively after this age (Schmid and others, 2010).

Imagine having a baby with colic. You feel helpless. You cannot do anything to quiet the baby down. There are few things more damaging to parental self-efficacy than an infant’s out-of-control crying (Keefe and others, 2006).

INTERVENTIONS: What Quiets a Young Baby?

WHAT SOOTHES A CRYING BABY? One strategy is to hold and rock the baby and provide a pacifier, a breast, a bottle, or anything that satisfies the need to suck. Another traditional approach is swaddling (wrapping) a newborn tight.

Interestingly, because it distances the baby from the mom’s body, swaddling has the downside of limiting skin-to-skin contact between caregiver and child (Kelmanson, 2013; Dumas and others, 2013). Continuous human touch is most effective at calming crying during the first days of life (Cecchini and others, 2013). The best example comes from the !Kung San hunter-gatherers of Botswana. In this collectivist culture, where mothers strap infants to their bodies and feed them on demand, the frequency of colic is dramatically reduced.

Kangaroo care, or using a baby sling, can even help premature infants grow (World Health Organization [WHO], 2003b). In one experiment, developmentalists had mothers with babies in an intensive care unit carry their infants in baby slings for one hour each day. Then, they compared these children’s development with that of a comparable group given standard care. At 6 months of age, the kangaroo-care babies scored higher on developmental tests. Their parents were rated as providing a more nurturing home environment, too (Feldman & Eidelman, 2003).

Kangaroo care, because it promotes this intense skin-to-skin bonding, is superior to swaddling—the standard Western baby-calming technique.

Burger/Phanie/Science Source

Imagine having your baby whisked away at birth to spend weeks with strangers. Now, think of being able to caress his tiny body, the sense of self-efficacy that would flow from helping him thrive. So it makes sense that any cuddling intervention can have an impact on the baby and the parent–child bond.

Another baby-calming strategy is infant massage. From helping premature infants gain weight, to treating toddler (and adult) sleep problems, to reducing old-age pain, massage enhances well-being from the beginning to the end of life (Field, Diego, & Hernandez-Reif, 2007, 2011).

We all know the power of a cuddle or a relaxing massage to soothe our troubles. Can holding and stroking in early infancy generally insulate us against stress? Consider this study with rats.

Because rodent mothers (like humans) differ in the “hands-on” contact they give their babies, researchers classified rats who had just given birth into high licking and grooming, average licking and grooming, and low licking and grooming groups. As adults, the lavishly licked and groomed rats reacted in a more placid way when exposed to stress (Menard & Hakvoort, 2007). These compelling studies support attachment parenting, a childcare strategy advocating prolonged breastfeeding; continuous kangaroo care; and cautioning parents against “training” infants to sleep through the night (more about this topic in the next section). The issue is that practicing this 24/7 parenting can sometimes add to the guilt burdening modern moms. Still the implication is clear. During infancy (and for as long as you can), keep touching and loving ’em up!

Cuddles calm us from day 1 to age 101. However, crying also undergoes fascinating developmental changes. The long car ride that magically quieted a 2-month-old evokes agony in a toddler who cannot stand to be confined. First, it’s swaddling, then watching a mobile, then seeing Mom enter the room that has the power to soothe. In preschool, it’s monsters that cause wailing; during elementary school and teenagerhood, it’s failing or being rejected by our social group. As emerging adults, we weep for lost love. Finally, among mature adults and old folks (as we reach Erikson’s stage of generativity), we stop crying for ourselves and cry when our loved ones are in pain. Our crying shows where we are developmentally throughout our lives!

Sleeping: The Main Newborn State

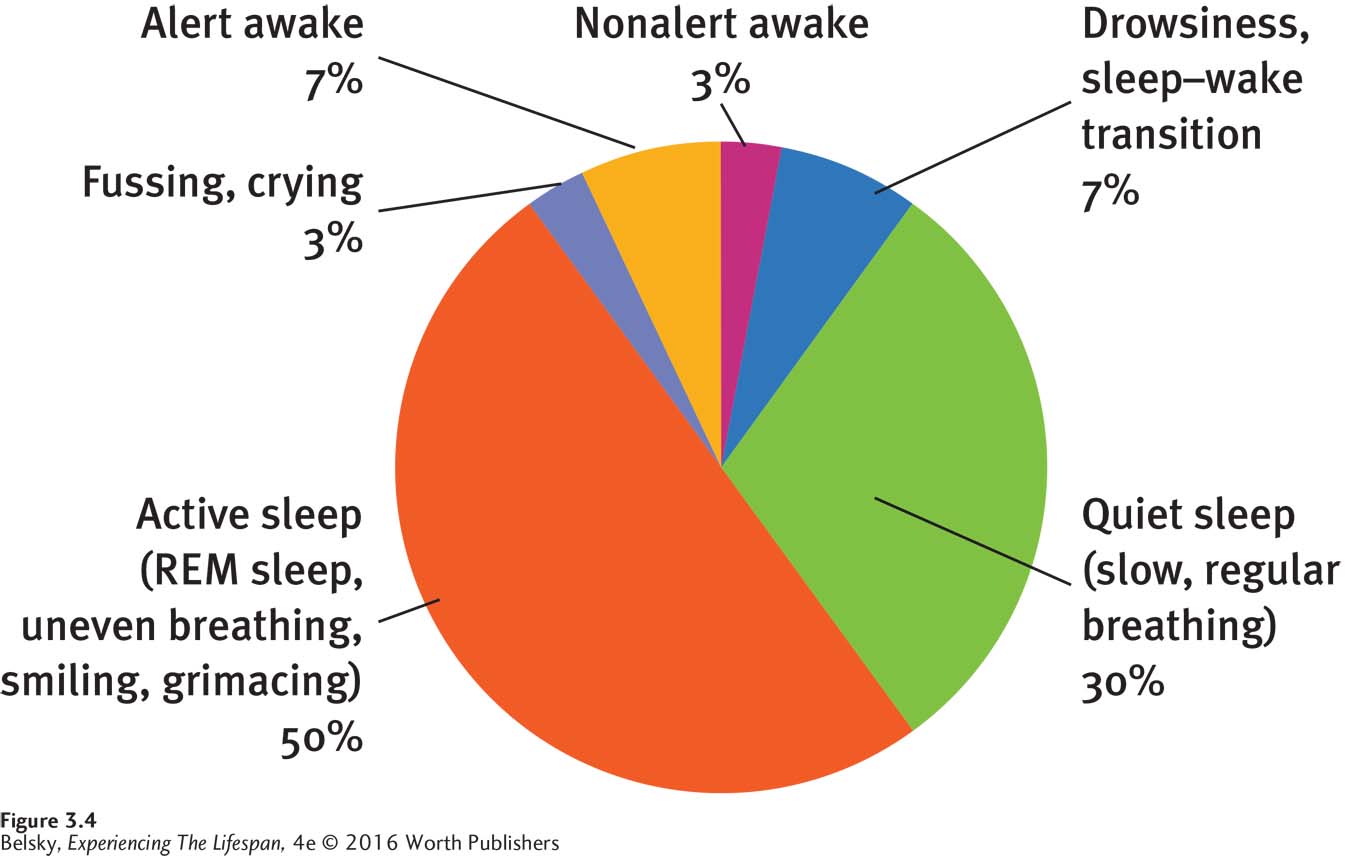

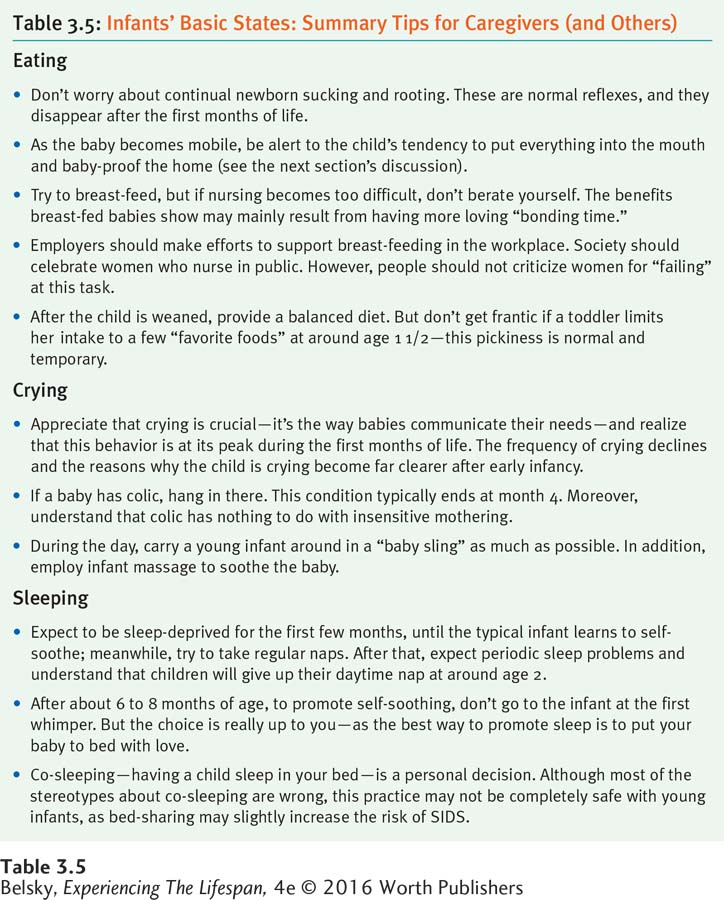

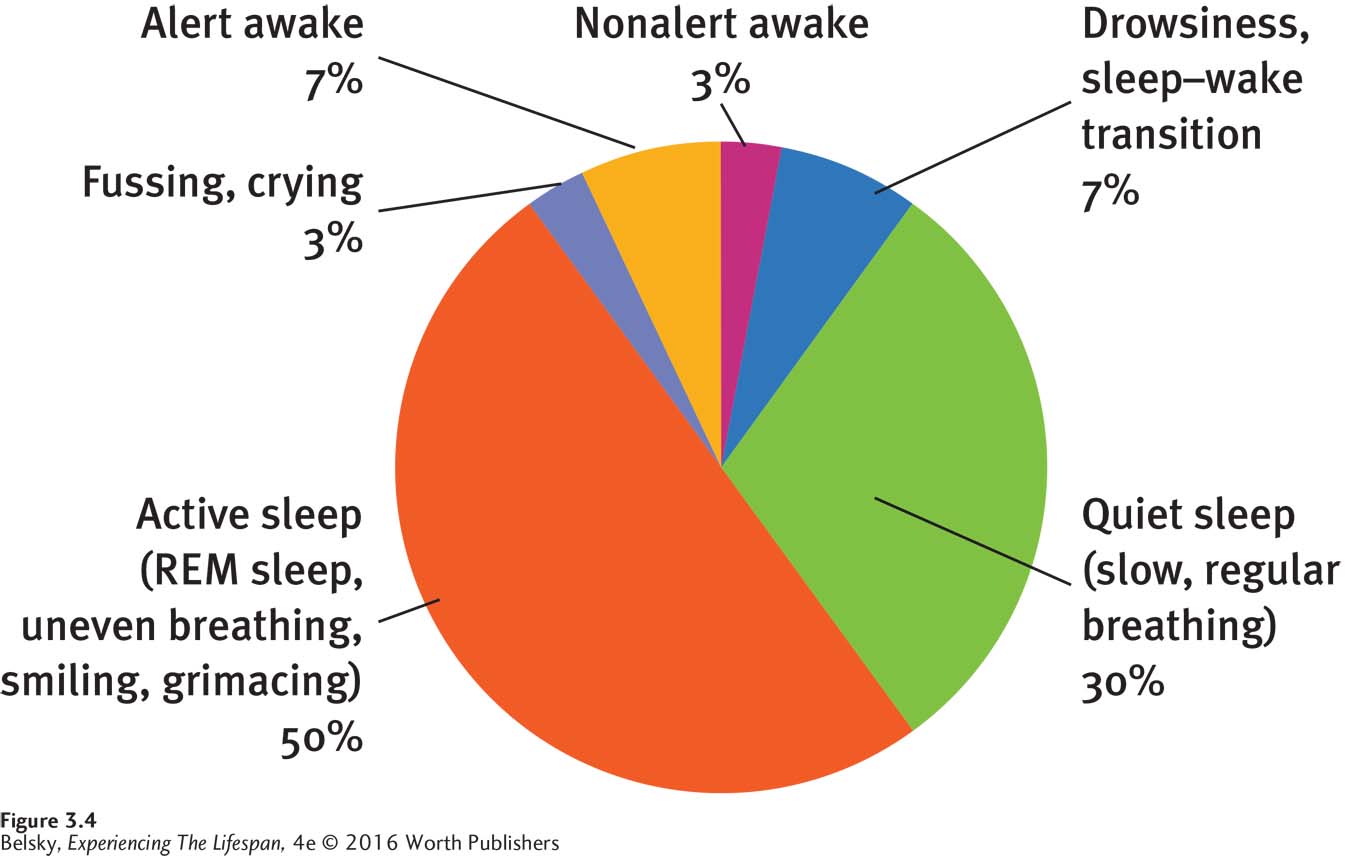

If crying is a crucial baby (and adult) communication signal, sleep is the quintessential newborn state. Visit a relative who has recently given birth. Will her baby be crying or eating? No, she is almost certain to be asleep. Full-term newborns typically sleep for 18 hours out of a 24-hour day. As Figure 3.4 shows, although they cycle through different stages, newborns are in the sleeping/drowsy phase about 90 percent of the time (Thoman & Whitney, 1990). And there is a reason for the saying, “She sleeps like a baby.” Perhaps because it mirrors the whooshing sound in the womb, noise helps newborns zone out. The problem for parents is that babies wake up and start wailing, like clockwork, every 3 to 4 hours.

Figure 3.4: Newborns sleep most of the time: During each 24-hour period, newborns cycle through various states of arousal. Notice, however, that babies spend the vast majority of their time either sleeping or in the getting-to-sleep phase.

Adapted from: Thoman & Whitney, 1990.

Developmental Changes: From Signaling, to Self-Soothing, to Shifts in REM Sleep

During the first year of life, infant sleep patterns adapt to the human world. Nighttime awakenings become less frequent. Then, by about 6 months of age, there is a milestone. The typical baby sleeps for 6 hours a night. At age 1, the typical pattern is roughly 12 hours of sleep a night, with an additional morning and afternoon nap. During year 2, the caretaker’s morning respite to do housework or rest is regretfully lost, as children give up the morning nap. Finally, by late preschool, sleep often (although not always) occurs only at night (Anders, Goodlin-Jones, & Zelenko, 1998).

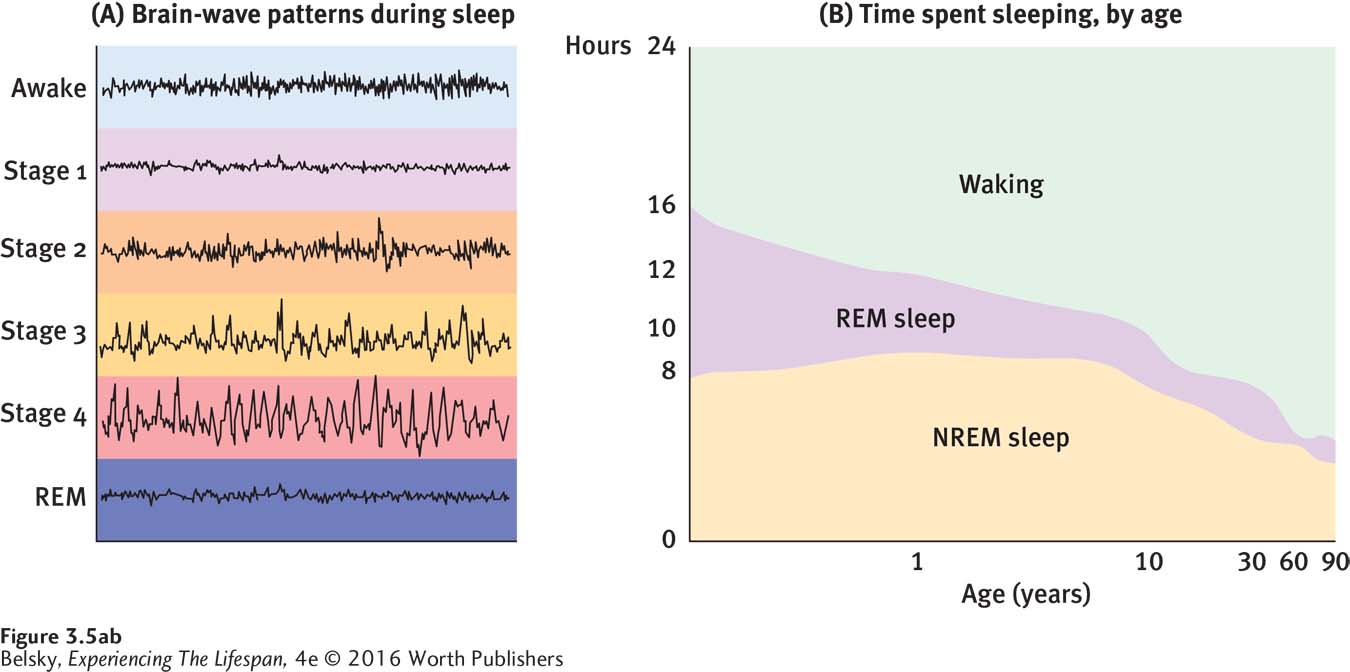

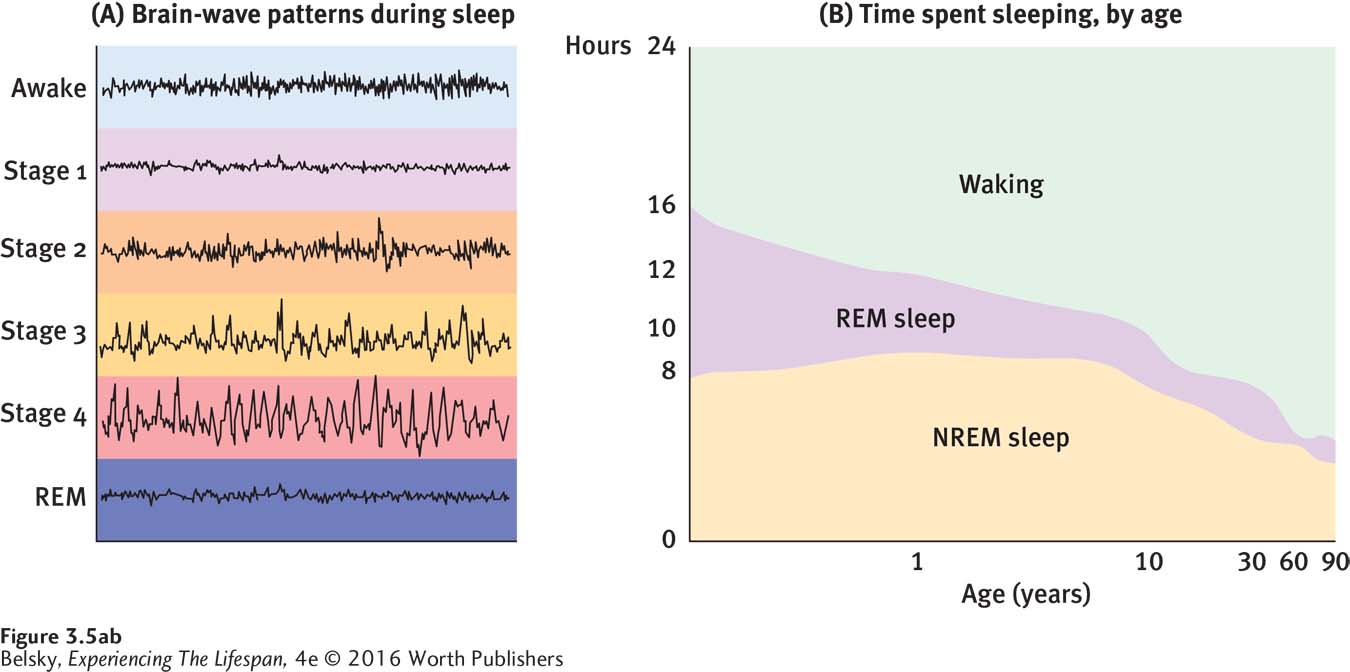

In addition to its length and on-again-off-again pattern, infant sleep differs physiologically from our adult pattern. When we fall asleep, we descend through four stages, involving progressively slower brain-wave frequencies, and then cycle back to REM sleep—a phase of rapid eye movement, when dreaming is intense and our brain-wave frequencies look virtually identical to when we are in the lightest sleep stage (see Figure 3.5). When infants fall asleep, they immediately enter REM and spend most of their time in this state. It is not until adolescence that we have the adult sleep cycle, with four distinct stages (Anders, Goodlin-Jones, & Zelenko, 1998).

Figure 3.5: Sleep brain waves and lifespan changes in sleep and wakefulness: In chart A, you can see the EEG patterns associated with the four stages of sleep that first appear during adolescence. After we fall asleep, our brain waves get progressively slower (these are the four stages of non-REM sleep) and then we enter the REM phase during which dreaming is intense. Now, notice in chart B the time young babies spend in REM. As REM sleep helps consolidate memory, is the incredible time babies spend in this phase crucial to absorbing the overwhelming amount of information that must be mastered during the first years of life?

Adapted from: Roffwarg, Muzio, & Dement, 1966.

Although parents are thrilled to say, “My child is sleeping though the night,” this statement is false. Babies never sleep continuously through the night. However, by about 6 months of age, many have the skill to become self-soothing. They put themselves back to sleep when they wake up (Goodlin-Jones and others, 2001).

Imagine being a new parent. Your first challenge is to get your baby to develop the skill of nighttime self-soothing. Around age 1, because your child is now put into the crib while still awake, there may be issues getting your baby to go to sleep. During preschool and elementary school, the sleep problem shifts again. Now, it’s concerns about getting the child into bed: “Mommy, can’t I stay up later? Do I have to turn off the lights?”

Although it may make them cranky, parents expect to be sleep-deprived with a young baby; but once a child has passed the 5- or 6-month milestone, they get agitated if the infant has never permitted them a full night’s sleep. Parents expect sleep problems when their child is ill or under stress, but not the zombielike irritability that comes from being chronically sleep-deprived for years. There is a poisonous bidirectional effect here: Children with chronic sleep problems produce irritable, stressed-out parents. Irritable, stressed-out parents produce childhood problems with sleep (Goldberg and others, 2013).

Infant sleep can be affected by everything from the mother’s mental state, to her relationship with her mate (Kim and Teti, 2014), to the stress of living in poverty (Sheridan and others, 2013). Moreover, a mother’s mental state may skew her perceptions about her infant’s sleep. In one survey, depressed moms were apt to label their babies as having serious sleep problems even when they did not (Goldberg and others, 2013).

So again, in understanding sleep during infancy, we need to look at the wider context—adopting the developmental systems approach. Moreover, we sometimes might take complaints about “a baby’s serious sleep issues” with a grain of salt. Child problems can be seen through the eye of the beholder—and that’s another theme I’ll be returning to in later chapters.

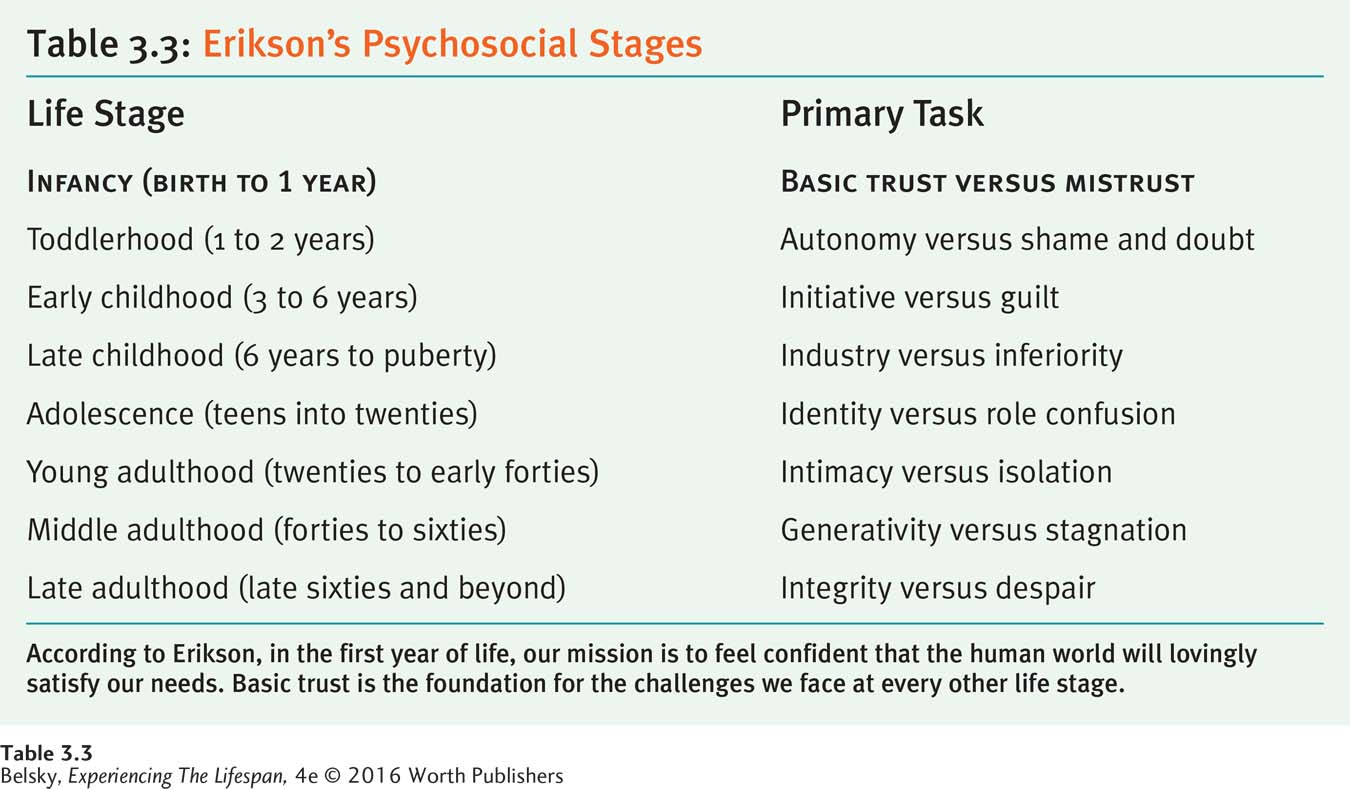

INTERVENTIONS: What Helps a Baby Self-Soothe?

What should parents do when their baby signals (cries out) from the crib? At one end of the continuum stand the behaviorists: “Don’t reinforce crying by responding—and be consistent. Never go in and comfort the baby lest you let a variable reinforcement schedule unfold, and the child will cry longer.” At the other, we have John Bowlby with his emphasis on the attachment bond, or Erik Erikson with his concept of basic trust (see Table 3.3). During the first year of life, both Bowlby and Erikson imply that caregivers should sensitively respond when an infant cries. These contrasting points of view evoke passions among parents, too:

I feel the basic lesson parents need to teach children is how to be independent, not to let your child rule your life, give him time to figure things out on his own, and not be attended to with every whimper.

I am going with my instincts and trying to be a good, caring mommy. Putting a baby in his crib to “cry it out” seems cruel. There is no such thing as spoiling an infant!

Where do you stand on this “Teach ’em” versus “Give unconditional love” controversy? Given that in a young baby the cortex has not fully come on-line, the behavioral “teach ‘em not to cry” doesn’t work during early infancy (Douglas and Hill, 2013; Stremler and others, 2013). But, by about month 7 or 8, it may be better to hang back, as babies who are quickly picked up may have more trouble learning to self-soothe (St. James-Roberts, 2007). So, if parents care vitally about getting a good night’s sleep, it’s best not to react to every nighttime whimper—but only when an infant approaches age 1 and can “learn” to get to sleep on her own.

By lovingly preparing his baby for bed, this man is helping ensure a better night’s sleep for both father and child. He also may be fostering basic trust—according to Erikson, the core foundation for having a good life.

Rolf Bruderer/Getty Images

Vigorous “settling activities”—carrying a child around at bedtime, making a big deal of an infant’s getting to sleep—are correlated with sleep difficulties at age 5 (Sheridan and others, 2013). Therefore, new parents might metaphorically err on the side of letting sleeping dogs lie, meaning not make excessive efforts to quiet the child. Still, this doesn’t mean don’t get involved!

When researchers videoed the bedtime behavior of mothers with infants, they found that women who responded sensitively to their babies around bedtime (those who used gentle, loving, pre-bed soothing routines) had children with fewer sleep problems (Teti and others, 2010). So, apart from any specific strategy, the real key to promoting infant sleep is to put a baby to bed with love.

This makes sense. Notice that when you feel disconnected from loved ones and anxious, you have trouble sleeping. To sleep soundly at any age, we need to feel cushioned by love.

The same principles—listen to the research, but act with love—apply to having a baby sleep in your bed.

To Co-sleep or Not to Co-sleep: A Cultural and Personal Choice

It was a standard nighttime routine in our house—one by one we’d wander in and say, “Mommy I’m afraid of witches and ghosts,” and soon all four of us would be happily nestled in our parents’ huge king-sized bed. I never realized that—in the l950s, in our uptight, middle-class New York suburb—this family bed-sharing qualified as a radical act.

How do you feel about co-sleeping or sharing a bed with a child? If you live in the United States and feel queasy about my parents’ decision, you are not alone. Until recently, experts in our individualistic society cautioned parents against co-sleeping (see Ferber, 1985). Behaviorists warned that sharing a bed with a child could produce “excessive dependency.” Freudian theorists implied that bed-sharing might place a child at risk for sexual abuse.

In collectivist cultures, people would laugh at these ideas (Latz, Wolf, & Lozoff, 1999; Yang & Hahn, 2002). Japanese parents, for instance, often separate to give each child a sleeping partner, because they believe co-sleeping is crucial to babies developing into caring, loving adults (Kitahara, 1989).

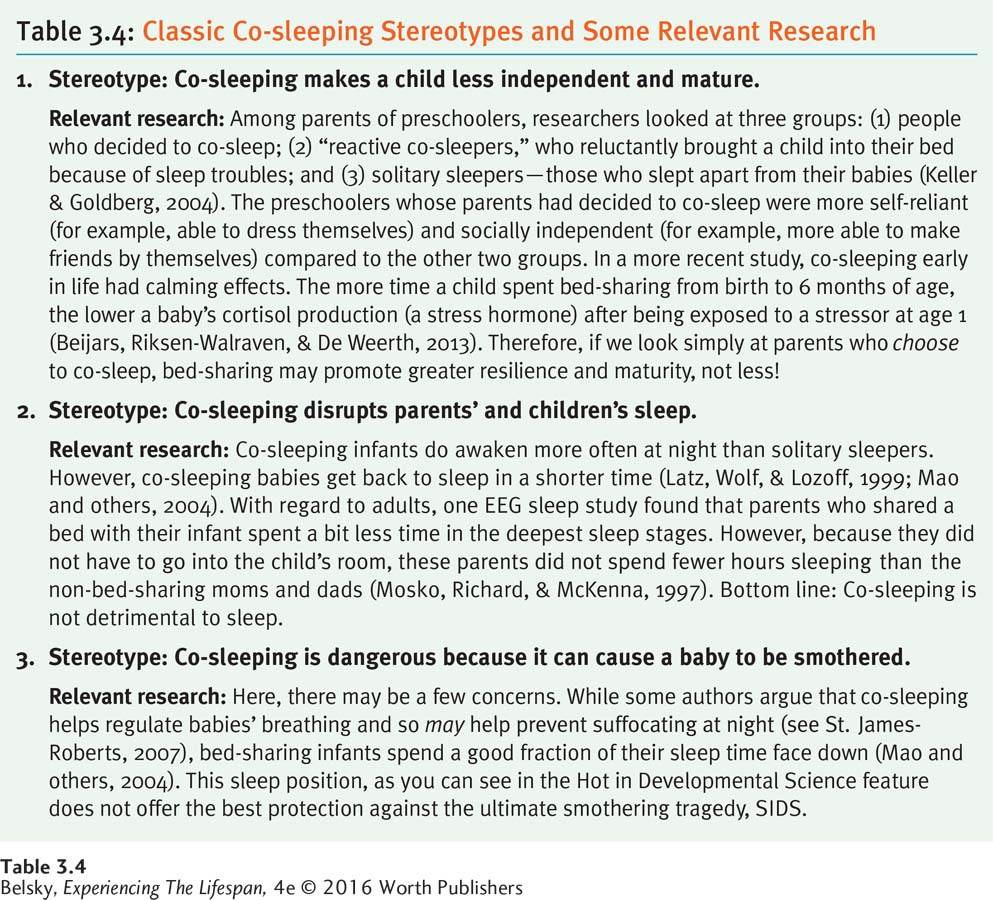

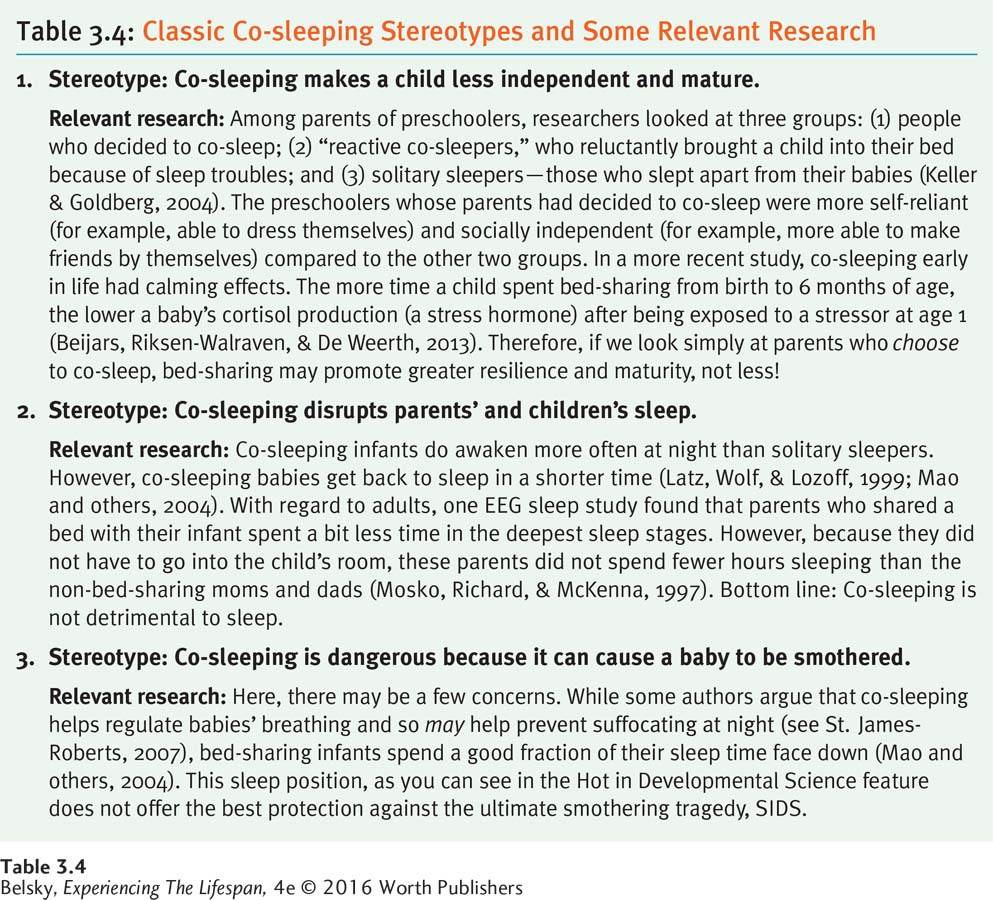

Today, in the West, co-sleeping has come out of the closet. Surveys show that, yes, like my parents, many people do it (Ball, 2007; Germo and others, 2007). But, because some mothers and fathers are still reluctant to admit that fact, Table 3.4 on page 86 provides three typical anti-bed-sharing stereotypes and some relevant research so you can decide which choice works best for you.

In this next section, we’ll explore the topic raised by the third stereotype in the table: What causes a baby to die while sleeping, or succumb to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)?

Hot in Developmental Science: SIDS

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) refers to the unexplained death of an apparently healthy infant, often while sleeping, during the first months of life. Although it strikes only about 1 in 1,000 U.S. babies, SIDS is a top-ranking cause of infant mortality in the developed world (Karns, 2001).

This portable sleeping basket is user friendly around the world, but in the Maori culture, it qualifies as culture friendly, too.

studiomoment/iStock/Getty Images

What causes SIDS? In autopsying infants who died during the peak risk zone for SIDS (about 1 to 10 months), researchers targeted abnormalities in a particular region of the brain. Specifically, SIDS infants had either too many or too few neurons in a section of the brain stem involved in coordinating tongue movements and maintaining the airway when we inhale (Lavezzi and others, 2010). SIDS has been linked to pathologies in the part of the brain stem producing cerebrospinal fluid, too (Lavezzi and others, 2013).

But even if SIDS is caused by biological pre-birth problems, this tragedy can have post-birth environmental causes. In particular, SIDS is linked to infants being inadvertently smothered, by being placed face down in a “fluffy” crib. During the early l990s, this evidence prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to urge parents to put infants to sleep on their backs. The “Back to Sleep” campaign worked, because from 1992 to 1997, there was a 43 percent reduction in SIDS deaths in the United States (Gore & DuBois, 1998).

Still, because placing babies on their backs can demand infants’ sleep separately in a crib, the “Back to Sleep” public health message contradicts the strong pro co-sleeping culture among non-Western groups. To circumvent this barrier, New Zealand scientists devised a strategy to permit Maori mothers to follow their traditional sleeping style and minimize the SIDS risk. They encouraged these women to return to another old-style practice—weaving a baby sleeping-basket. By placing this basket on parents’ beds, co-sleeping has now become scientifically “correct” (Ball & Volpe, 2013)!

Table 3.5 offers a section summary in the form of practical tips for caregivers dealing with infants’ eating, crying, and sleeping. Now it’s time to move on to sensory development and moving into the world.