3.4 Cognition

93

Why do infants have an incredible hunger to explore, to reach, to touch, to get into every cleanser-

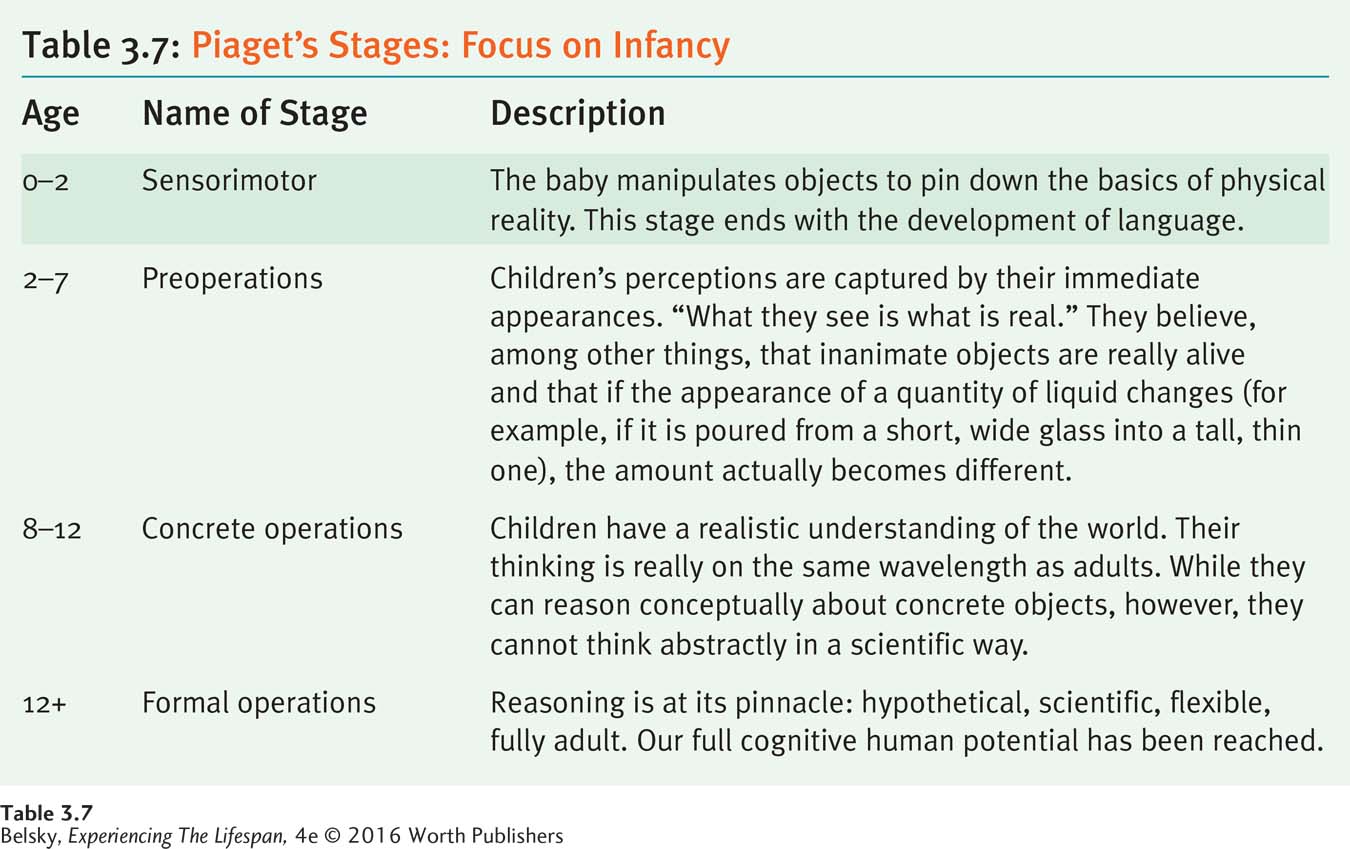

Imagine stepping out onto Mars. You would roam the new environment, exploring the rocks and the sand. While exercising your walking schema, or habitual way of physically navigating, you would need to make drastic changes. On Mars, with its minimal gravity, when you took your normal earthling stride, you would probably bounce up 20 feet. Just like a newly crawling infant, you would have to accommodate, and in the process reach a higher mental equilibrium, or a better understanding of life. Moreover, as a scientist, you would not be satisfied to perform each movement only once. The way to pin down the physics of this planet would be to repeat each action over and over again. Now you have the basic principles of Jean Piaget’s sensorimotor stage (see Table 3.7).

Piaget’s Sensorimotor Stage

Specifically, Piaget believed that during our first two years on this planet, our mission is to make sense of physical reality by exploring the world through our senses. Just as in the above Mars example, as they assimilate, or fit the outer world to what they are capable of doing, infants accommodate and so gradually mentally advance. (Remember my example in Chapter 1 of how, in the process of assimilating this information to your current knowledge schemas or mental slots, you are accommodating and so expanding what you know.)

Let’s take the “everything into the mouth” schema that figures so prominently during the first year of life. As babies mouth each new object—

Circular Reactions: Habits That Pin Down Reality

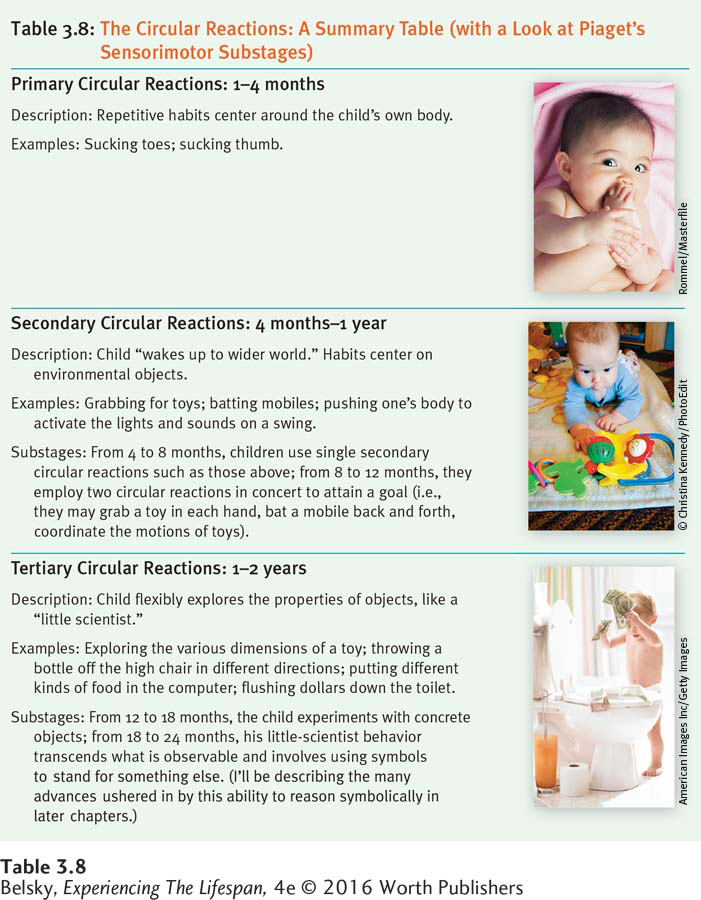

By observing his own three children, Piaget discovered that driving all these advances were what he called circular reactions—habits, or action-

94

From the newborn reflexes, during months 1 to 4, primary circular reactions develop. These are repetitive actions centered on the child’s body. A thumb randomly makes contact with his mouth, and a 2-

At around 4 months of age, secondary circular reactions appear. As the cortex blossoms and the child begins to reach, action-

Lucienne at 0:4 [4 months] is lying in her bassinet. I hang a doll over her feet which . . . sets in motion the schema of shakes. Her feet reach the doll . . . and give it a violent movement which Lucienne surveys with delight . . . . After the first shakes, Lucienne makes slow foot movements as though to grasp and explore . . . . When she tries to kick the doll, and misses . . . she begins again very slowly until she succeeds [without looking at her feet].

(Piaget, 1950, p. 159 [as cited in Flavell, 1963, p. 103])

During the next few months, secondary circular reactions become better coordinated. By about 8 months of age, babies can simultaneously employ two circular reactions, using both grasping and kicking together to explore the world.

Then, around a baby’s first birthday, tertiary circular reactions appear. Now, the child is no longer constrained by stereotyped schemas. He can operate just like a real scientist, flexibly changing his behavior to make sense of the world. A toddler becomes captivated by the toilet, throwing toys and different types of paper into the bowl. At dinner, he gleefully spits his food out at varying velocities and hurls his bottle off the high chair in different directions to see where it lands.

How important are circular reactions in infancy? Spend time with a young baby, as she bats at her mobile or joyously pinwheels her legs. Try to prevent a 1-

Piaget’s concept of circular reactions offers a new perspective on those obsessions that drive adults crazy during what researchers call the little-

Why do specific circular reactions, such as flushing dollar bills down the toilet, become irresistible during the little-

Tracking Early Thinking

How do we know when infants begin to think? According to Piaget, one hallmark of thinking is deferred imitation—

But the most important sign of emerging reasoning is means–

95

If you have access to a 1-

Object Permanence: Believing in a Stable World

Object permanence refers to knowing that objects exist even when we no longer see them—

96

Piaget’s observations suggested that during babies’ first few months, life is a series of disappearing pictures. If an enticing image, such as her mother, passed her line of sight, Lucienne would stare at the place from which the image had vanished as if it would reappear out of thin air. (The relevant phrase here is “out of sight, out of mind.”) Then, around month 5, when the secondary circular reactions are first flowering, there was a milestone. An object dropped out of sight and Lucienne leaned over to look for it, suggesting that she knew it existed independently of her gaze. Still, this sense of a stable object was fragile. The baby quickly abandoned her search after Piaget covered that object with his hand.

Hunting for hidden objects under covers becomes an absorbing game as children approach age one. Still, around 9 or 10 months of age, children make a surprising mistake called the A-

See if you can perform this classic test if you have access to a 10-

After their first birthday, children seem to master the basic principle. Move an object to a new hiding place and they look for it in the correct location. However, as Piaget found when he used this strategy but covered the object with his hand, object permanence does not fully emerge until children are almost 2 years old.

Emerging object permanence explains many puzzles about development. Why does peek-

Emerging object permanence offers a wonderful perspective on why younger babies are so laid back when you remove an interesting object, and then become possessive by their second year of life. Those toddler tantrums do not signal a new, awful personality trait called “the terrible twos.” They simply show that children are smarter. They have the cognitive skills to know that objects still exist when you take them away.

Finally, the concept of object permanence, or fascination with disappearing objects, plus means–

But during the first year of life there is no need to arrive with any toy. Buy a toy for an infant and he will push it aside to play with the box. Your nephew probably prefers fiddling with the TV remote to any object from Toys R Us. Toys only become interesting once we realize that they are different from real life. So, a desire for dolls or action figures—

Critiquing Piaget

97

Piaget’s insights have transformed the way we think about childhood. Research confirms the fact that children are, at heart, little scientists. The passion to decode the world is built into being human from our first months of life (Gopnik, 2010). However, Piaget’s timing was seriously off. Piaget’s trouble was that he had to rely on babies’ actions (for instance, taking covers off hidden objects) to figure out what they knew. He did not have creative strategies, like preferential looking and habituation, to decode what babies’ understand before they can physically respond. Using these techniques, researchers realized that young infants know far more about life than this master theorist ever believed. Specifically, scientists now know that:

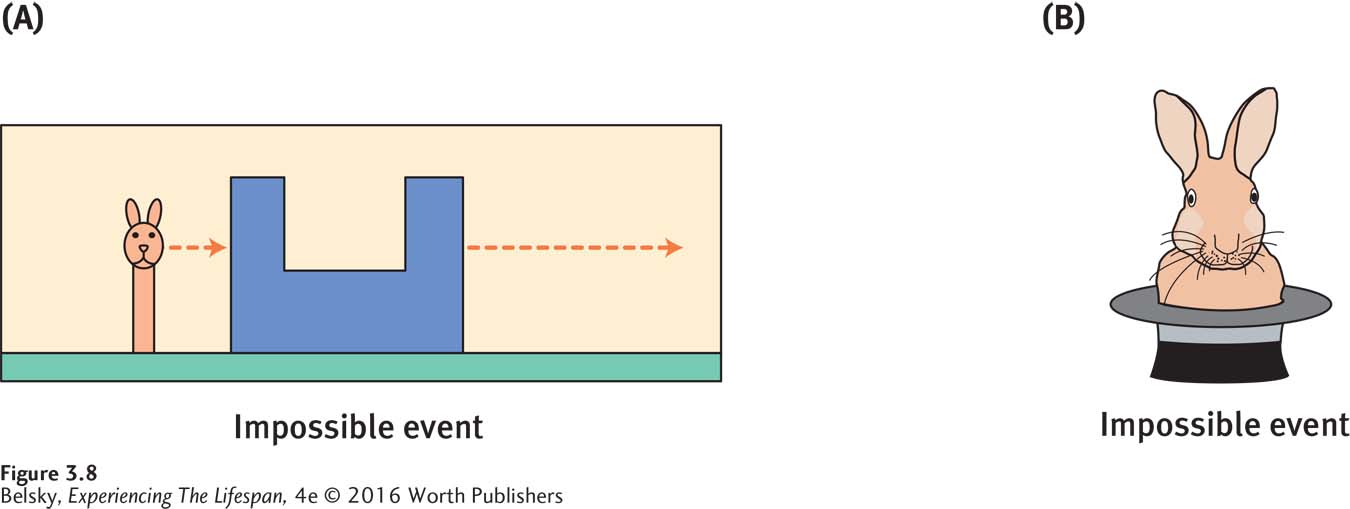

Infants grasp the basics of physical reality well before age 1. To demonstrate this point, developmentalist Renée Baillargeon (1993) presented young babies with physically impossible events such as showing a traveling rabbit that never appeared in a gap it had to pass through to reach its place on the other side (illustrated in Figure 3.8A). Even 5-

month- olds looked astonished when they saw these impossible events. You could almost hear them thinking, “I know that’s not the way objects should behave.” Infants’ understanding of physical reality develops gradually. For instance, while Baillargeon discovered that the impossible event of the traveling rabbit in the figure provoked astonishment around month 5, other research shows it takes until age 1 for babies to master other basics about the world, such as the fact that you cannot take a large rabbit out of a little container (shown in Figure 3.8B). (As an aside, that explains why “magic” suddenly becomes interesting only around age 2 or 3.) Therefore, rather than viewing development in huge qualitative stages, many contemporary researchers adopt a more specific approach: focusing on particular mental processes such as memory; decoding step by step how cognition gradually emerges.

Information-

98

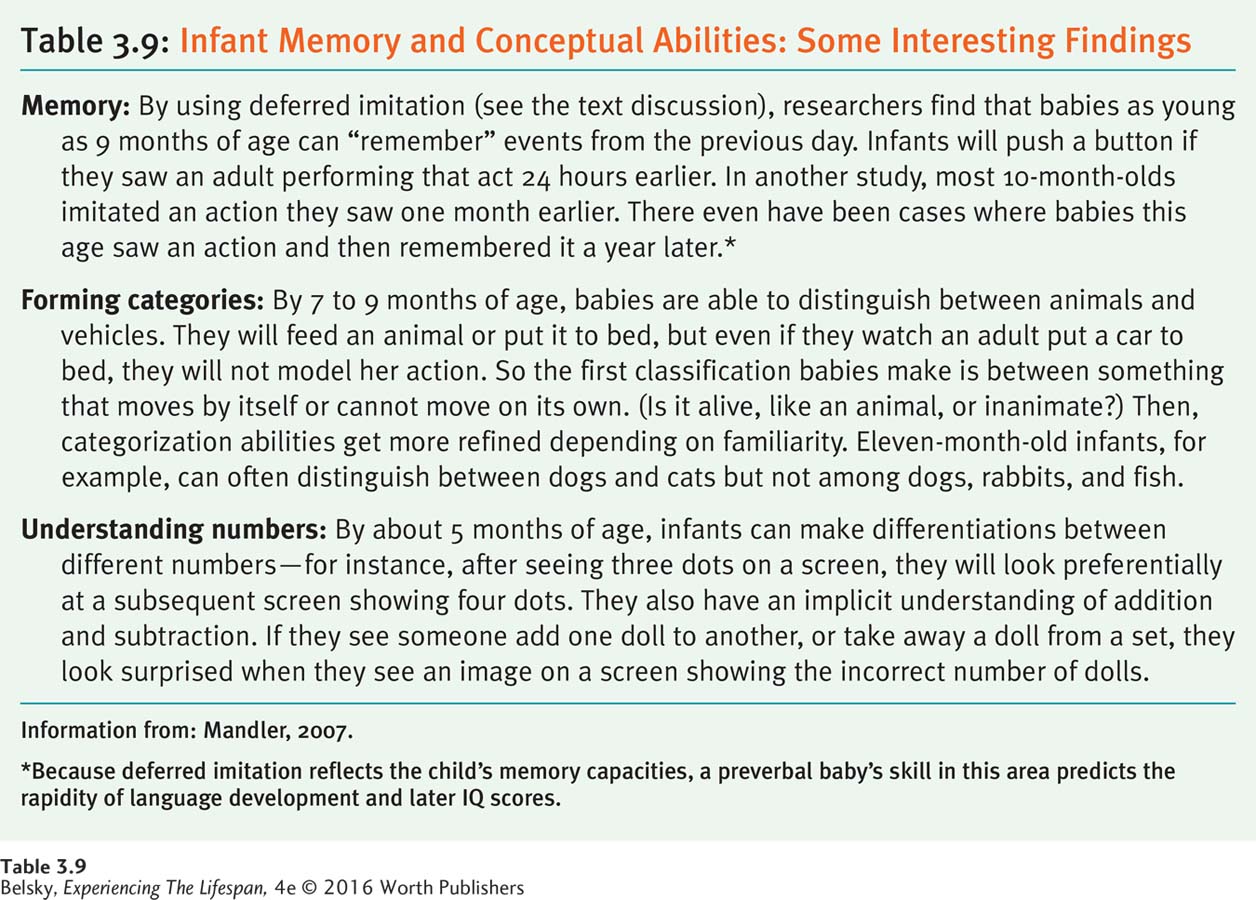

Table 3.9 showcases insights about babies’ memories and mathematical capacities, derived from using this gradual, specific approach. Stay tuned for Chapters 5 and 13, to see how information processing sheds light on memory and thinking during elementary school and old age. Now, it’s time to tackle another question: What do babies understand about human minds?

Tackling the Core of What Makes Us Human: Infant Social Cognition

Social cognition refers to any skill related to managing and decoding people’s emotions, and getting along with other human beings. One hallmark of being human is that we are always making inferences about people’s feelings and goals, based on their actions. (“He’s running, so he must be late.” “She slammed the door in my face, so she must be angry.”) When do these judgments first occur? Piaget would say not before age 2 (or much later) because infants in the sensorimotor period can’t think conceptually. Here, too, Piaget was incorrect. Babies make sophisticated judgments about intentions at an incredibly young age!

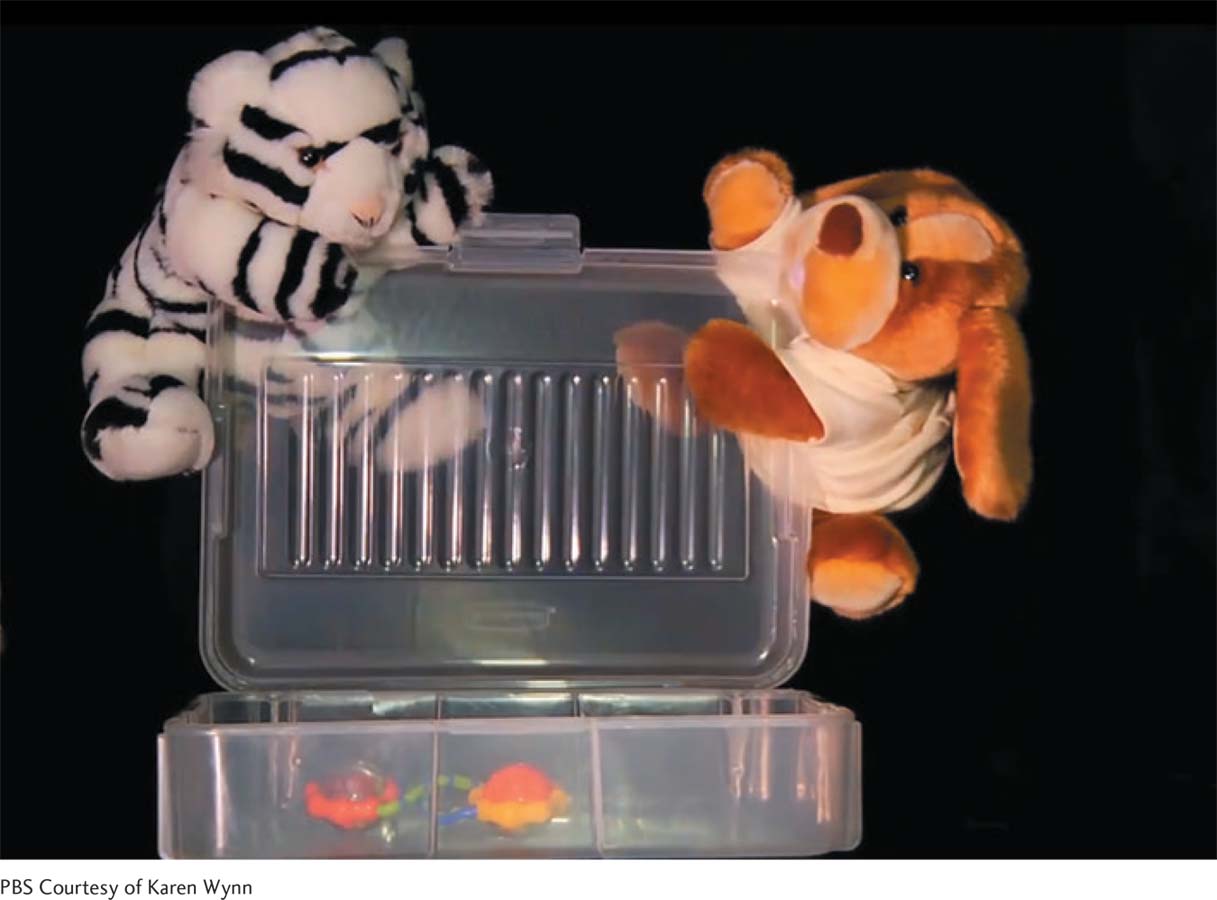

The strategy here is to first show infants a video of a puppet or stuffed animal helping another puppet complete a challenging task (the nice puppet). In the next scene, another puppet hinders the stuffed animal from reaching his goal (the mean puppet). (See the photos at right.) Then, the experimenter offers the baby both puppets and sees if she preferentially grabs for either one. And guess what? By the time they can reach (at about month 5), most infants grasp the nice puppet rather than the puppet that acted “mean” (Hamlin & Wynn, 2011; Hamlin, 2013).

This remarkable finding suggests we clue into motivations such as “She’s not nice!” months before we begin to speak (Hamlin, 2013). More astonishing, 8-

99

But I cannot leave you with the sense that our species is primed to be mini-

Using a similar procedure, the same research group found that 8-

In sum, during our second six months on this planet, we can decode intentions—

Tying It All Together

Question 3.15

You are working at a child-

Circular reaction = Darien; means–end behavior = Jai; object permanence = Sam.

Question 3.16

Jose, while an avid Piaget fan, has to admit that in important ways, this master theorist was wrong. Jose can legitimately make which two criticisms? (1) Cognition develops gradually, not in stages; (2) Infants understand human motivations; (3) Babies understand the basic properties of objects at birth.

Cognition develops gradually rather than in distinct stages; infants understand human motivations.

Question 3.17

Baby Sara watches her big brother hit the dog. Based on the research in this section, Sara might first understand her brother is being “mean” (choose one) months before/at/months after age 1.

Baby Sara should pick up this idea months before age 1.