3.5 Language: The Endpoint of Infancy

Piaget believed that language signals the end of the sensorimotor period because this ability requires understanding a symbol stands for something else. True, in order to master language, you must grasp the idea that the abstract word-

Nature, Nurture, and the Passion to Learn Language

The essential property of language is elasticity. How can I come up with this new sentence, and why can you understand its meaning, although you have never seen it before? Why does every language have a grammar, with nouns, verbs, and rules for organizing words into sentences? According to linguist Noam Chomsky, the reason is that humans are biologically programmed to make “language,” via what he labeled the language acquisition device (LAD).

Chomsky developed his nature-

100

Still, Skinner is correct in one respect. I speak English instead of Mandarin Chinese because I grew up in New York City, not Beijing. So the way our genetic program for making language gets expressed depends on our environment. Once again, nature plus nurture work together to explain every activity of life!

Currently, developmentalists adopt a social-

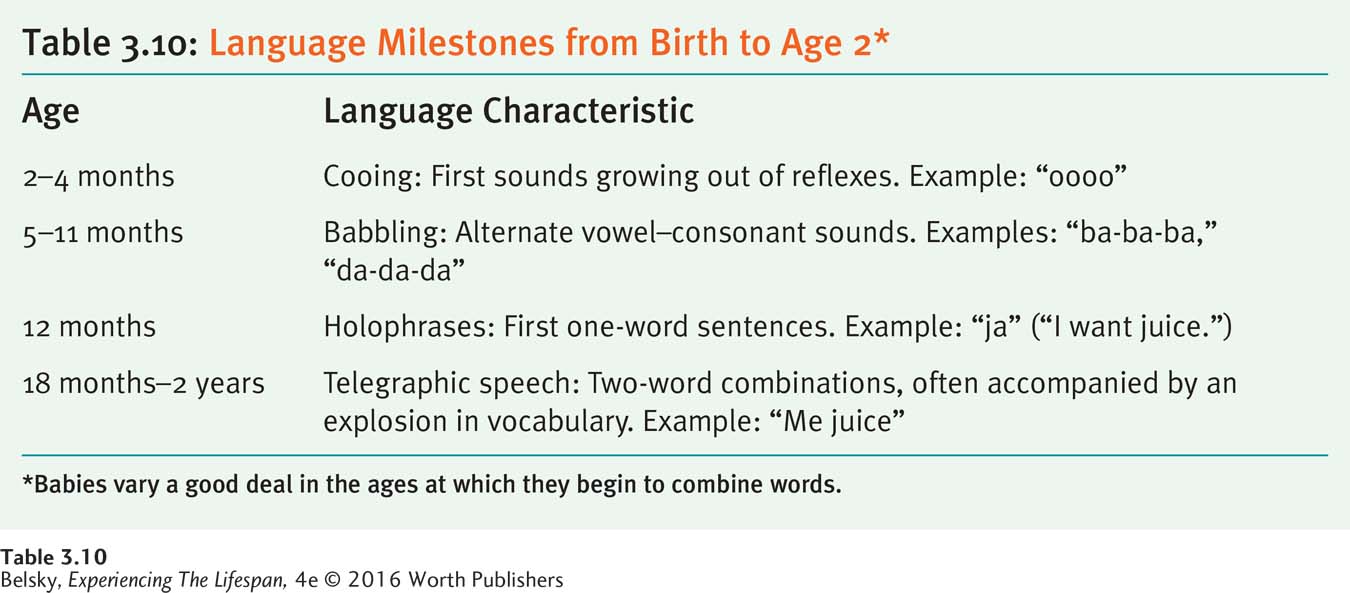

Tracking Emerging Language

The pathway to producing language occurs in stages. Out of the reflexive crying of the newborn period comes cooing (oooh sounds) at about month 4. At around month 6, delightful vocal circular reactions called babbling emerge. Babbles are alternating consonant and vowel sounds, such as “da da da,” that infants playfully repeat with variations of intonation and pitch.

The first word emerges out of the babble at around 11 months, although that exact landmark is difficult to define. There is little more reinforcing to paternal pride than when your 8-

Children accumulate their first 50 or so words, centering on the important items in their world (people, toys, and food), slowly (Nelson, 1974). Then, typically between ages 1 1/2 and 2, there is a vocabulary explosion as the child begins to combine words. Because children pare communication down to its essentials, just like an old-

Just as with the other infant achievements described in this chapter, developmentalists are passionate to trace language to its roots. It turns out, for instance, that newborns are prewired to gravitate to the sounds of living things—

101

Caregivers promote these achievements by continually talking to babies. Around the world, they train infants in language by using infant-

Infant-

Babies identify individual words better when they are uttered in exaggerated IDS tones (Thiessen, Hill, & Saffran, 2005). When adults are learning a new language, they also benefit from the slow, repetitive IDS style. Therefore, rather than being just for babies, IDS is a strategy that teaches language across the board (Ratner, 2013). In fact, notice that when you are teaching a person any new skill (or, as you will see in Chapter 14, when talking to an older person you perceive as impaired,) you, too, are apt to automatically use IDS!

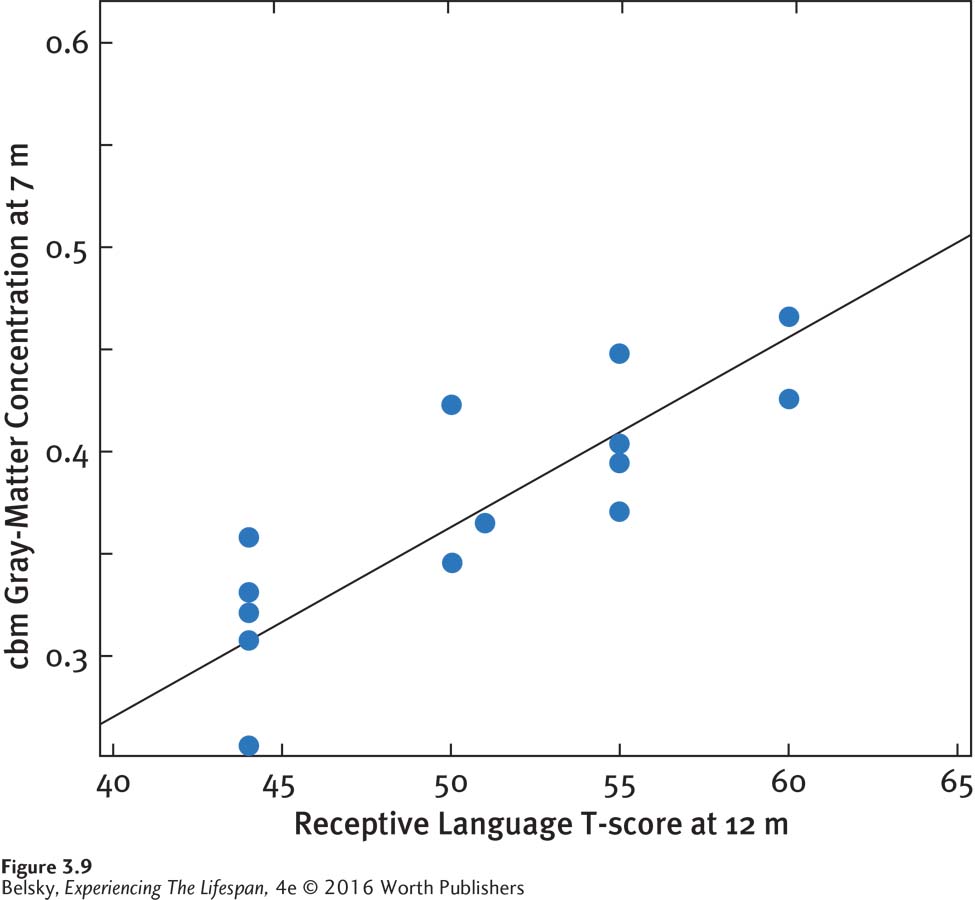

The close link between brain development at 7 months of age and children’s speech understanding at age 1, shown in Figure 3.9, suggests that we can physically “see” the roots of language before that talent appears (Deniz Can, Richards, and Kuhl, 2013; see also Dean and others, 2014). But even if this growth rate is mainly genetically programmed (meaning due to biological differences), parents who use more IDS communications have babies who speak at a younger age (Ratner, 2013).

IDS is different than other talk. You don’t hear this speech style on TV, at the dinner table, or on videos designed to produce Einstein’s at 8 months of age. IDS kicks in only when we communicate with babies one on one. So, if parents are passionate to accelerate language, investing millions in learning tools seems a distant second best to spending time talking to a child (Ratner, 2013)!

102

A basic message of this chapter is that—

Tying It All Together

Question 3.18

“We learn to speak by getting reinforced for saying what we want.” “We are biologically programmed to learn language.” “Babies are passionate to communicate.” Identify the theoretical perspective reflected in each of these statements: Skinner’s operant conditioning perspective; Chomsky’s language acquisition device; a social-

The idea that we learn language by getting reinforced reflects Skinner’s operant conditioning perspective; Chomsky hypothesized that we are biologically programmed to acquire language; the social-

Question 3.19

Baby Ginny is 4 months old; baby Jamal is about 7 months old; baby Sam is 1 year old; baby David is 2 years old. Identify each child’s probable language stage by choosing from the following items: babbling; cooing; telegraphic speech; holophrases.

Baby Ginny is cooing; baby Jamal is babbling; baby Sam is speaking in holophrases (one-

Question 3.20

A friend makes fun of adults who use baby talk. Given the information in this section, is her teasing justified?

No, your friend is wrong!!! Baby talk—