4.3 Toddlerhood: Age of Autonomy and Shame and Doubt

Imagine time-

Autonomy involves everything from the thrill a 2-

125

Erikson used the words shame and doubt to refer to the situation when a toddler’s drive for autonomy is not fulfilled. But feeling shameful and doubtful is also vital to shedding babyhood and entering the human world. During their first year of life, infants show joy, fear, and anger. At age 2, more complicated, uniquely human emotions emerge—

Socialization: The Challenge for 2-

Shame and pride are vital in another respect. They are essential to socialization—being taught to live in the human community.

Parents begin socializing their children by making requests such as “eat that cookie,” as early as 6 months of age. There are cultural differences, with Indian mothers giving their babies more instructions and getting higher rates of compliance than do U.S. moms (Reddy and others, 2013).

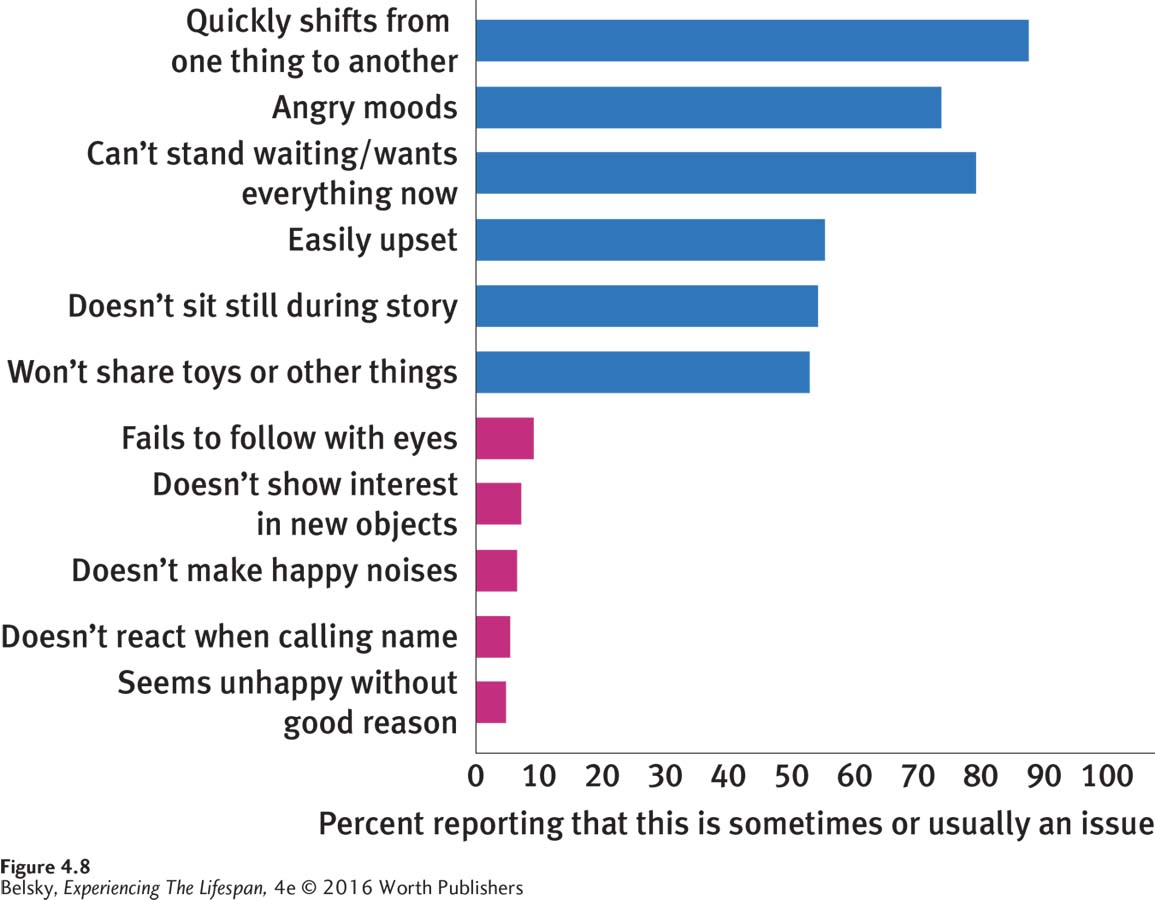

When does the U.S. socialization pressure heat up? For answers, developmentalists surveyed middle-

Figure 4.8 shows just how difficult it is for 1-

Not unexpectedly, children’s ability to “listen to a parent in their head” and stop doing what they want improves dramatically from age 2 to 4 (Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, 2001). Still, the really interesting question is: Who is better or worse at this feat of self-

Again, the marked differences in self-

126

What temperamental traits provoke early compliance? Here the answer comes as no surprise. Fearful toddlers are more obedient (Aksan & Kochanska, 2004; see also the How Do We Know box). Exuberant, joyful, fearless, intrepid toddler-

HOW DO WE KNOW . . .

that shy and exuberant children differ dramatically in self-

How do researchers measure the toddler temperaments discussed below? How do they test later self-

In the fear eliciting “treatment,” a child enters a room filled with frightening toy objects, such as a dinosaur with huge teeth or a black box covered with spider webs. The experimenter asks that boy or girl to perform a mildly risky act, such as putting a hand into the box. To measure anger, the researchers restrain a child in a car seat and then rate how frustrated the toddler gets. To tap into exuberance, the researchers entertain a child with a set of funny puppets. Will the toddler respond with gales of laughter or be more reserved?

Several years later, the researchers set up a situation provoking noncompliance by asking the child, now age 4, to perform an impossible task (throw Velcro balls at a target from a long distance without looking) to get a prize. Then, they leave the room and watch through a one-

Toddlers at the high end of the fearless, joyous, and angry continuum, show less “morality” at age 4. Without the strong inhibition of fear, their exuberant “get closer” impulses are difficult to dampen down. So they succumb to temptation, sneak closer, and look directly at the target as they hurl the balls (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003).

Being Exuberant and Being Shy

Adam [was a vigorous, happy baby who] began walking at 9 months. From then on, it seemed as though he could never stop.

(10 months) Adam . . . refuses to be carried anywhere. . . . He trips over objects, falls down, bumps himself.

(12 months) The word osside appears. . . . Adam stands by the door, banging at it and repeating this magic word again and again.

(19 months) Adam begins attending a toddler group. . . . The first day, Adam climbs to the highest rung of the climbing structure and falls down. . . . The second day, Adam upturns a heavy wooden bench. . . . The fourth day, the teacher [devastates Adam’s mother] when she says, “I think Adam is not ready for this.”

. . .

(13 months) (Erin begins to talk in sentences the same week as she takes her first steps.) . . . Rather suddenly, Erin becomes quite shy. . . . She cries when her mother leaves the room, and insists on following her everywhere.

(15 months) Erin and her parents go to the birthday party of a little friend. . . . For the first half-

127

(18 months) Erin’s mother takes her to a toddlers’ gym. Erin watches the children . . . with a “tight little face.” . . . Her mother berates herself for raising such a timid child.

(Lieberman, 1993, pp. 83–

Observe any group of 1-

The classic longitudinal studies tracing children with shy temperaments have been carried out by Jerome Kagan. Kagan (1994; see also Degnan, Almas, & Fox, 2010) classifies about 1 in 5 middle-

This tendency to be inhibited is also moderately “genetic” (Smith and others, 2012), and we can get clues to its appearance very early in life. At 4 months of age, toddlers destined to be inhibited excessively fret and cry (Moehler and others, 2008; Marysko and others, 2010). At 9 months of age, they are less able to ignore distracting stimuli such as flashing lights or background noise. Their attention wanders to any off-

Inhibited toddlers are more prone to be fearful throughout childhood (Degnan, Almas, & Fox, 2010). They overfocus on threatening stimuli in their teens (Pérez-

Still, if you think you have come a long way in conquering your incredible childhood shyness, you are probably correct. Many anxious toddlers (and exuberant explorers) get less inhibited as they move into elementary school and the teenage years (Degnan, Almas, & Fox, 2010; Pérez-

INTERVENTIONS: Providing the Right Temperament–Socialization Fit

Faced with a temperamentally timid toddler such as Erin or an exuberant explorer like Adam or Thomas, what can parents do?

Socializing a Shy Baby

In dealing with fearful children, parents’ impulse is to back off (“Erin is emotionally fragile, so I won’t pressure her to go to day care or clean up her toys”). This “treat ’em like glass” approach is apt to backfire, provoking more wariness down the road (Natsuaki and others, 2013). With shy children, be caring and responsive (Barnett and others, 2010; Degnan, Almas, & Fox, 2010), but provide a gentle push. Exposing a shy toddler to supportive new social situations—

128

Raising a Rambunctious Toddler

When faced with fearless explorers, like Adam and Thomas, it’s tempting to adopt a discipline style called power assertion—yelling, screaming, and hitting a child who is bouncing off the walls (Verhoeven and others, 2010). Once they have defined their toddler as “impossible to control,” parents are prone to come down more harshly, misreading defiance even into benign acts. Another reaction is to give up—

Both strategies are counterproductive. Power assertion strongly predicts behavior problems down the road (Brotman and others, 2009; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Leve and others, 2010). Disengaging from discipline robs the child of the tools to modify his behavior. Plus, it conveys the message, “You are out of control and there is nothing I can do.”

The key to reducing “noncompliance” in any toddler is to offer positive guidance; meaning to set limits in a calm, clear way (Christopher and others, 2013). With fearless explorers, it’s especially crucial to foster a secure attachment, getting a child to want to be good for mom and dad (Kochanska and Kim, 2013). As my husband insightfully commented, “Punishment doesn’t matter much to Thomas. What he does, he does for your love.”

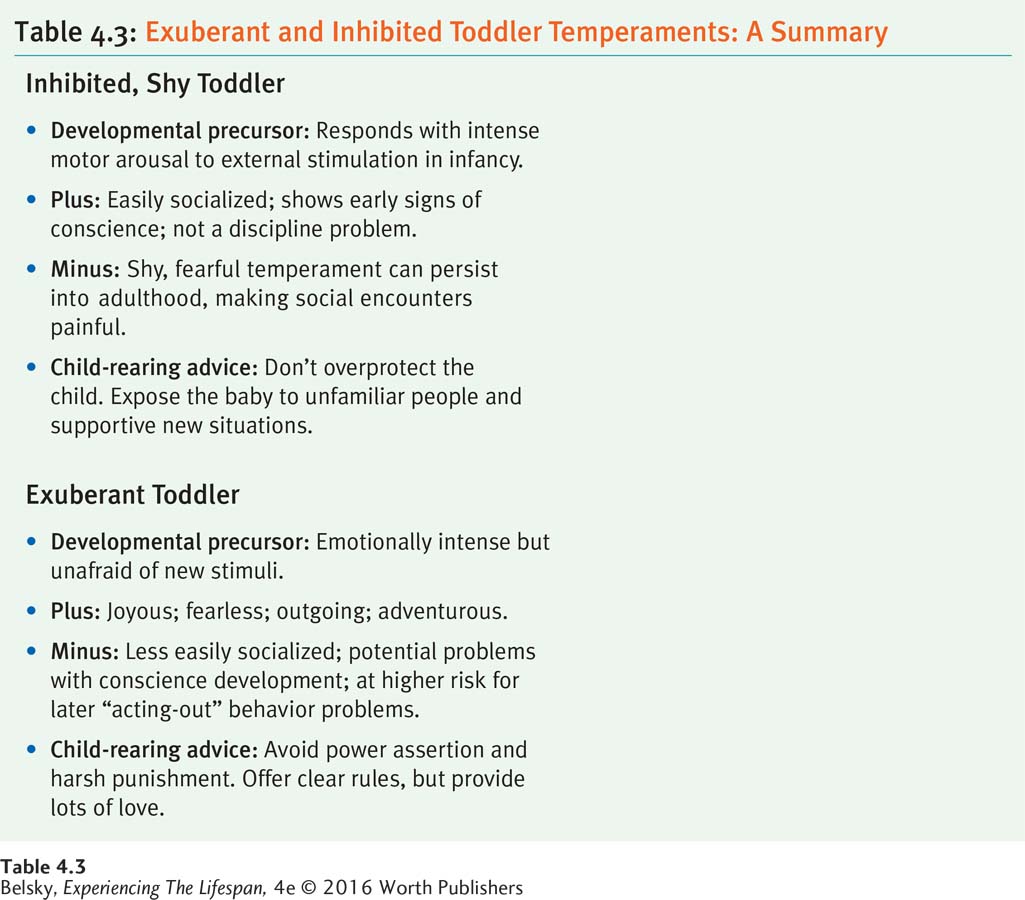

Table 4.3 offers a summary of this discussion, showing these different toddler temperaments, their infant precursors, their pluses and potential later dangers, and lessons for socializing each kind of child. Now let’s look at some general temperament-

An Overall Strategy for Temperamentally Friendly Childrearing

Clearly, one key to socializing children is to provide a secure, loving attachment. However, another is to understand each child’s temperament and work with that unique behavioral style. This principle was demonstrated in the classic study I mentioned earlier, in which developmentalists classified babies as “easy,” “slow-

129

In following the difficult babies into elementary school, the researchers found that intense infants were more likely to have problems with their teachers and peers (Thomas & Chess, 1977; Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968). However, some children learned to compensate for their biology and to shine. The key, the researchers discovered, lay in a parenting strategy labeled goodness of fit. Parents who carefully arranged their children’s lives to minimize their vulnerabilities and accentuate their strengths had infants who later did well.

Understanding that their child was overwhelmed by stimuli, these parents kept the environment calm. They did not get hysterical when faced with their child’s distress. They may have offered a quiet environment for studying and encouraged their child to do activities that took advantage of his or her talents. They went overboard to provide their child with a placid, nurturing, low-

Here, too, emerging genetic studies suggest these parents were right. Again, researchers find that children may be genetically predisposed to be reactive or relatively immune to environmental events (Ellis and others, 2011a). In typical settings, sensitive babies can be labeled “difficult” because they are wired to react negatively to changes. These same infants however, may flourish when the environment is exceptionally calm (for review, see Belsky & Pleuss, 2009). In fact, in one study, when “environment reactive” children were put in a nurturing, placid environment, they performed better than their laid-

I must emphasize that this genetically oriented research is in its infancy. Each study I’ve highlighted in this chapter has targeted a different environment-

How can we promote goodness of fit, or person–

Tying It All Together

Question 4.10

If Amanda has recently turned 2, what predictions are you not justified in making about her?

Amanda wants to be independent, yet closely attached.

Amanda is beginning to show signs of self-

awareness and can possibly feel shame. Amanda’s parents haven’t begun to discipline her yet.

c. Parents typically start serious discipline around age 2.

Question 4.11

To a colleague at work who confides that he’s worried about his timid toddler, what words of comfort can you offer?

You might tell him that most children grow out of their shyness, even if they do not completely shed this temperamental tendency. But be sure to stress the advantages of being shy: His baby will be easier to socialize, not likely to be a behavior problem, and may have a stronger conscience, too.

Question 4.12

Think back to your own childhood: Did you fit into either the shy or exuberant temperament type? How did your parents cope with your personality style?

These answers will be totally your own.