5.2 Physical Development

Look at children of different ages and you will immediately see the cephalocaudal principle of physical growth discussed in Chapters 2 and 3. Three-

138

Now visit a playground or take out your childhood artwork to see the mass-

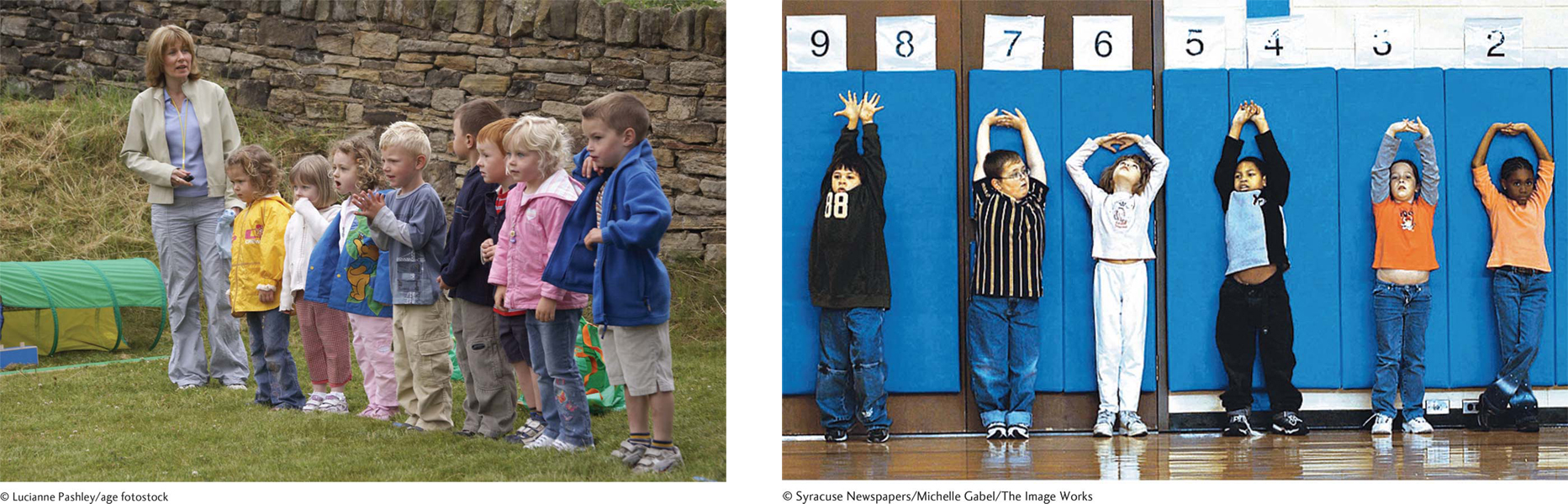

Two Types of Motor Talents

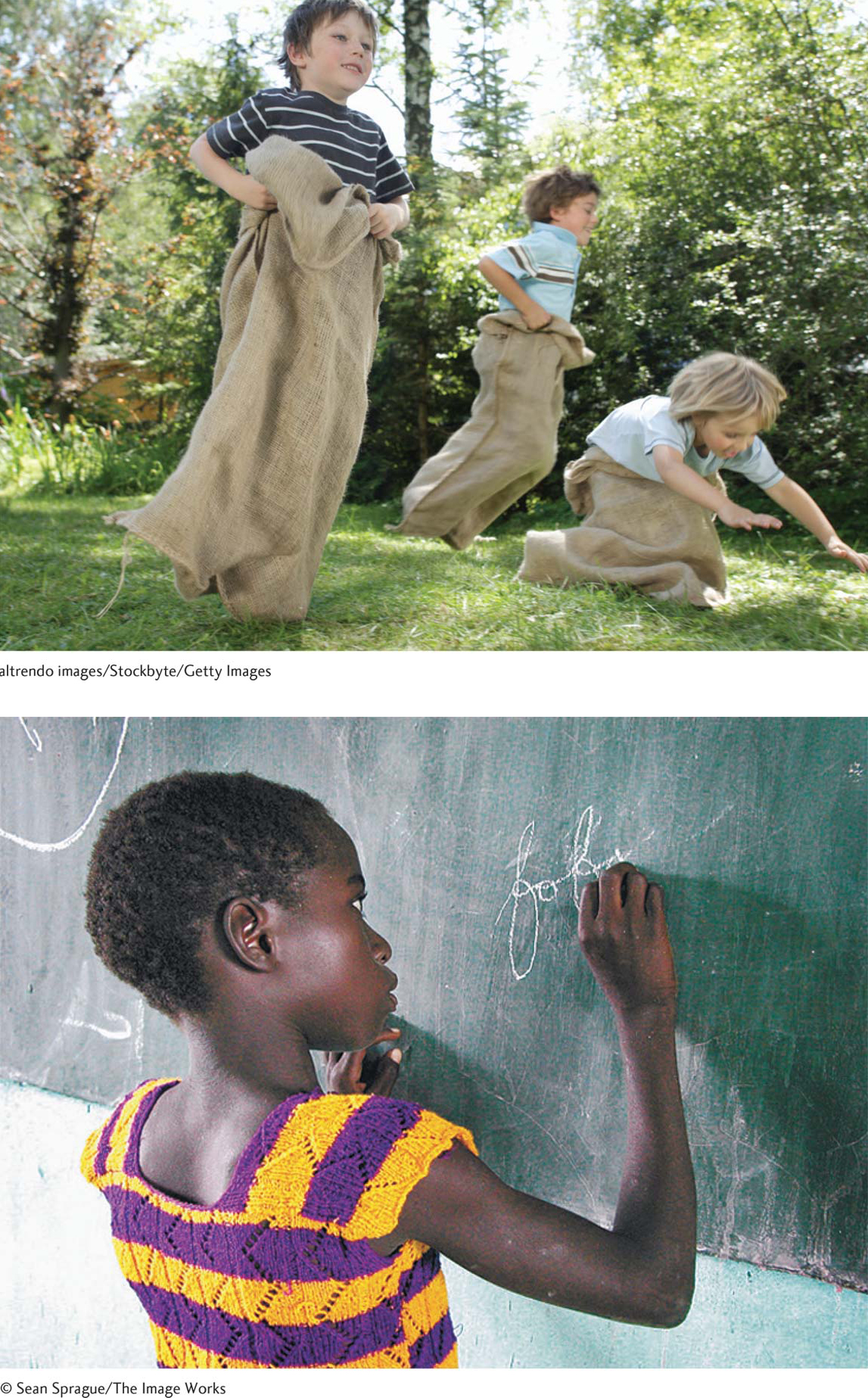

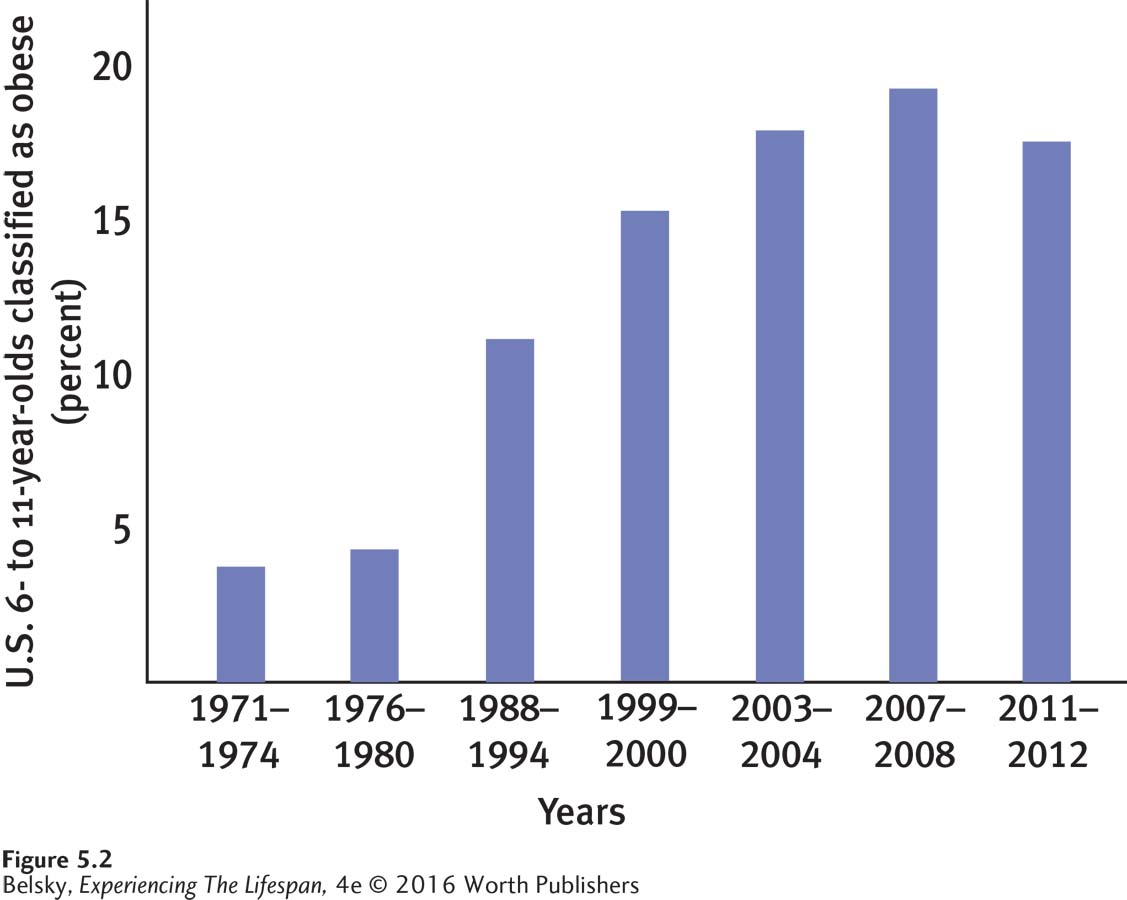

Developmentalists divide physical skills into two categories. Gross motor skills refer to large muscle movements, such as running, climbing, and hopping. Fine motor skills involve small, coordinated movements, such as drawing faces and writing one’s name.

The stereotype that boys are better at gross motor abilities and girls at fine motor tasks is true—

If a preschooler has precocious physical abilities, will that child be advanced at school? The answer is yes, if we look at complex fine motor skills. Researchers asked 5-

This study suggests that to improve academic abilities we might train young children to reproduce images, in addition to teaching them numbers or how to sound out words. The problem is that pressuring (forcing) preschoolers to unwillingly perform physical tasks can be counterproductive. During early childhood, we should provide activities—

Now that we’ve scanned what normally happens physically, let’s look at what can go wrong.

Threats to Growth and Motor Skills

139

I discussed the main threat to growth and motor skills in Chapter 3: lack of food. In addition to causing stunting, undernutrition impairs gross and fine motor skills because it compromises the development of the bones, muscles, and brain. Most important, when children are hungry, they are too tired to move and so don’t get the experience crucial to developing their physical skills.

During the 1980s, researchers observed how undernourished children in rural Nepal maximized their growth by cutting down on play (Anderson & Mitchell, 1984). Play does more than exercise our bodies. It can help prime neural development and is crucial in promoting social cognition, helping children learn how to get along with their peers. So, the lethargy that malnutrition produces is as detrimental to children’s relationships as it is to their bodies and brains. Notice how, after skipping just one meal, you become listless, unwilling to talk, less interested in reaching out to people in a loving way.

Keeping in mind that undernutrition remains the top-

Childhood Obesity

Have you ever wondered about the source of the numbers in the charts showing the ideal weights for people of different heights? These statistics come from a regular U.S. national poll called the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES). Since the 1960s, the federal government has literally been measuring the size of Americans by charting caloric intakes, heights, and weights. The familiar statistic researchers use to monitor overweight is body mass index (BMI)—the ratio of a person’s weight to height. If the BMI is at or over the 85 percentile for the norms in the first poll, a child is defined as “overweight.” At the 95th percentile or above, the label is “obese.”

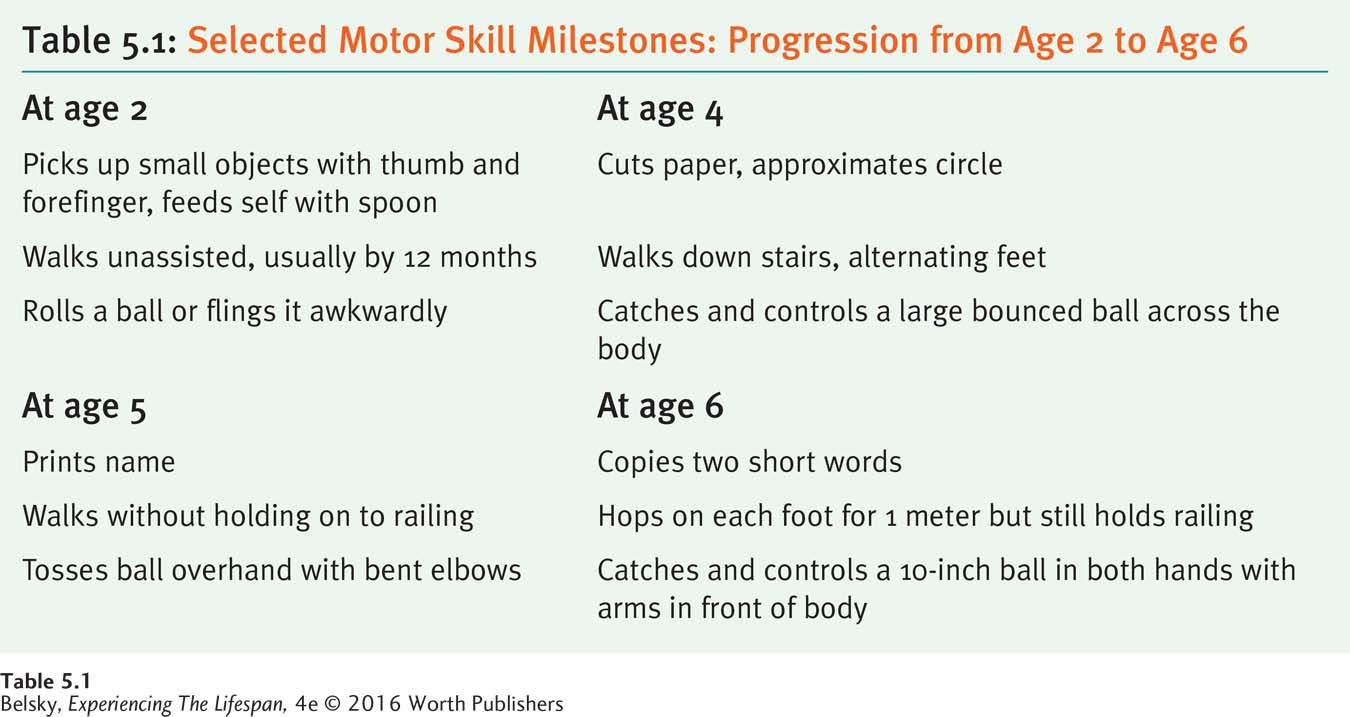

Exploring the Epidemic’s Size

Childhood obesity ballooned about 35 years ago. During the late 1980s, the NHANES researchers were astonished to find that the fraction of obese elementary school children had doubled over a decade (see Figure 5.2). By 2012, roughly 1 out of every 6 North American children and teens was obese—

This late twentieth-

The shape of the threat, however, differs by nation. Obesity rates are lower in Scandinavia than in Mediterranean countries and the United States (Faeh & Bopp, 2010). In the developing world, childhood obesity is most common in cities and among affluent boys and girls (Berkowitz & Stunkard, 2002). In the United States, obesity rates are higher in rural areas (Davis and others, 2011), and far more common among the poor. There is also an ethnic dimension to the epidemic. Obesity is most prevalent among Latino and African American boys and girls (Boonpleng and others, 2013).

140

The great news is that in recent years, the prevalence of preschool obesity declined significantly, from roughly 14 percent in 2003–

Exploring the Epidemic’s Wider-

The reason lies in a perfect storm of societal “obesogenic” forces (Finegood, Merth, & Rutter, 2010; Swinburn & deSilva-

Lack of exercise plays an important role. With the Internet and TV, playing outside—

To tackle the weight of obesity-

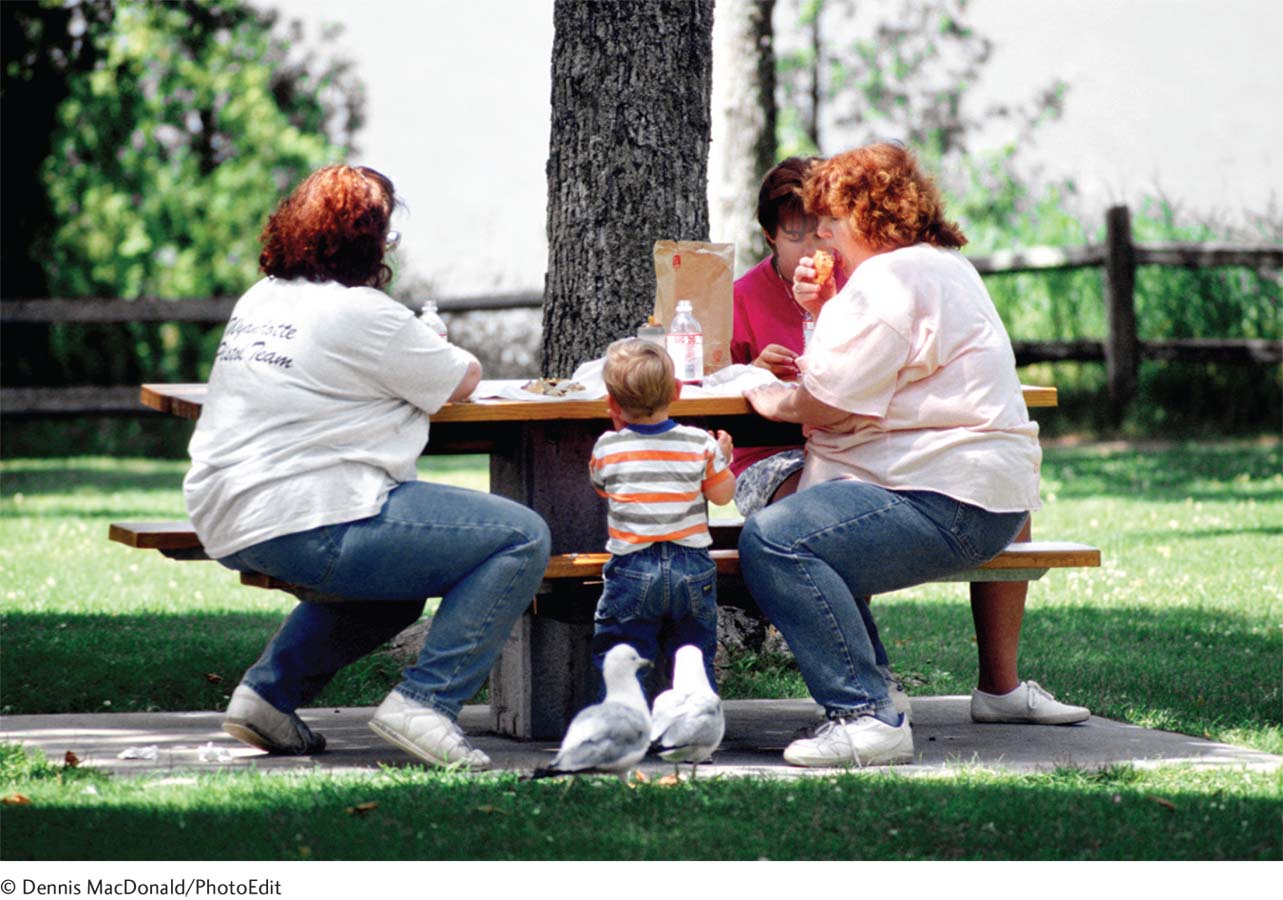

It’s tempting to see this striking correlation (overweight parents have overweight children) and conclude that obesity is genetic, so there is nothing we can do. Or perhaps you (like many of us) have mentally accused overweight parents for loading themselves and their kids up with fattening foods.

Exploring the Epidemic’s Epigenetics

Tantalizing research suggests obesity has a partly epigenetic, pre-

Interestingly, scientists can predict this predisposition soon after we emerge from the womb. Rapid weight gain during infancy and early childhood is a strong predictor of later obesity—

Exploring the Epidemic’s Consequences

This lifelong battle takes a social toll. From being less likely to get hired (Puhl & Heuer, 2010) or finish college (Fowler-

141

These barriers begin soon after babyhood (Puhl & Latner, 2007). In a classic study, elementary schoolers were shown pictures of an overweight child, a child in a wheelchair, another with facial disfigurements, and several others with disabilities. When asked, “Whom would you choose as a friend?” the children ranked the obese boy or girl last. By age 3, children describe chubby boys and girls as “mean” and “sloppy.” So it’s no wonder that, in the West, overweight children are at risk of suffering from depression in their teens (Pitrou and others, 2010; Sánchez-

Attitudes are less harsh in other cultures. In Bangladesh, obesity actually promotes high self-

This pressure can backfire (no surprise), producing binge eating (Matton and others, 2013), compounding an elementary schooler’s already fragile self-

Let’s understand where these adults are coming from. Faced with the prejudices their children are already enduring, parents want to protect their sons and daughters from further pain. As one woman reported, “He’s a highly sensitive child, and he’s got very low self-

Moreover—

INTERVENTIONS: Limiting Overweight

My discussion shows that the best strategy to control overweight is to start early on. Rather than intervening during preschool or elementary school, when self-

Never put a pregnant woman on a diet. Instead, point out that excessive weight gain during pregnancy may have obesity-

promoting effects— not just for the mom, but also for her child. (Taking steps to reduce prematurity rates would also help.) Limit excessive feeding during the first year of life. Overweight women are more apt to soothe their infants by immediately offering the bottle or breast (Anzman-

Frasca and others, 2013). Depressed women also may promote infant weight gain, by overlabeling their babies as fussy and prematurely providing solid food (Gaffney and others, 2013). Mothers, one study showed, can be taught to minimize nursing for non- hunger related distress (Paul and others, 2011). Encourage every new parent to feed until her baby is satisfied, and not beyond. Understand that limiting intake is especially difficult for overweight children (Skoranski and others, 2013) and that obesity control programs are apt to be rejected if they seem insulting to parents or attack children’s self-

esteem. Make interventions palatable by having families serve as the experts in what they should do (Jurkowski and others, 2013).

142

Without denying that we are making strides in combatting preschool obesity, I think you might agree that self-

Tying It All Together

Question 5.4

Jessica has terrific gross motor skills but trouble with fine motor skills. Select the two sports from this list that Jessica would be most likely to excel at: long-

Long-

Question 5.5

The prevalence of obesity is _____ during preschool. (rising/leveling off/declining)

The prevalence of obesity is declining during preschool.

Question 5.6

Melanie is a toddler. In predicting her chance of later weight struggles, you might look to (pick right alternative): Melanie’s mom’s weight; whether Melanie was born premature; Melanie’s weight again during the past year; all of these forces.

All of these forces predict later overweight.

Question 5.7

The best age to intervene to prevent obesity is: (a) birth–

The best age to intervene to prevent obesity is birth age 1.

Question 5.8

Your friend wants to develop a child obesity intervention at your local church. Explain in a sentence why some people might be unwilling to participate, and what your friend might do to ensure more families enroll.

Because parents—