5.3 Cognitive Development

In this section, we turn to the heart of this chapter: cognition. How do children develop intellectually as they travel from age 3 into elementary school? In our search for answers, we explore three perspectives on mental growth, starting with that master theorist Jean Piaget.

Piaget’s Preoperational and Concrete Operational Stages

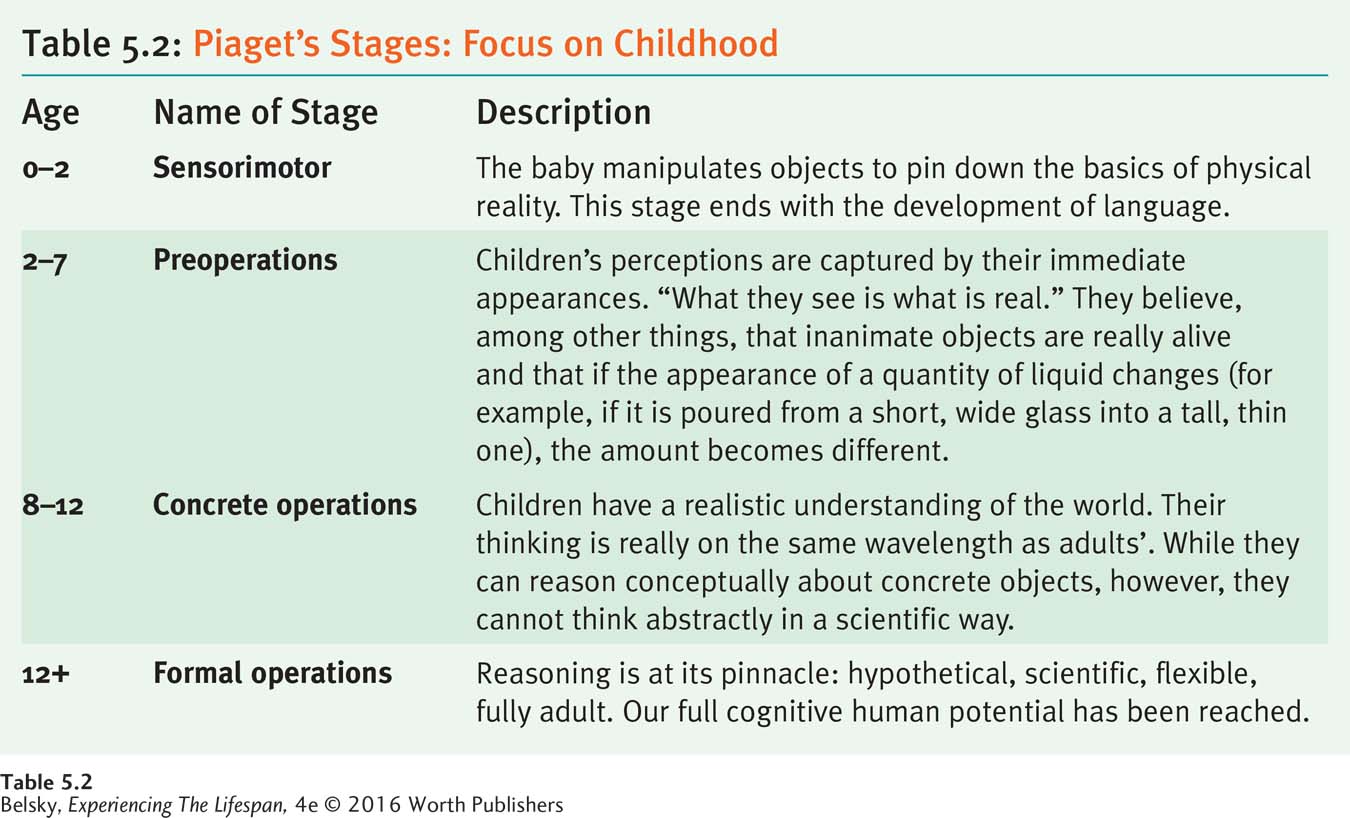

Recall from Chapter 1 that Piaget believed that through assimilation (fitting new information into their existing cognitive structures) and accommodation (changing those cognitive slots to fit input from the world), children undergo qualitatively different stages of cognitive growth. In Chapter 3, I discussed Piaget’s sensorimotor stage. Now, it’s time to tackle the next two stages, in Table 5.2: the preoperational and concrete operational stages.

As their names imply, we need to discuss these two stages together. Preoperational thinking is defined by what children are missing—

When children leave infancy and enter the stage of preoperational thought, they have made tremendous mental strides. Still, their thinking seems on a different planet from that of adults. The problem is that preoperational children are unable to look beyond the way objects immediately appear. By about age 7 or 8, children can mentally transcend what first hits their eye. They have entered the concrete operational stage.

The Preoperational Stage: Taking the World at Face Value

You saw vivid examples of this “from another planet” preschool thinking in my chapter-

143

Strange Ideas About Substances

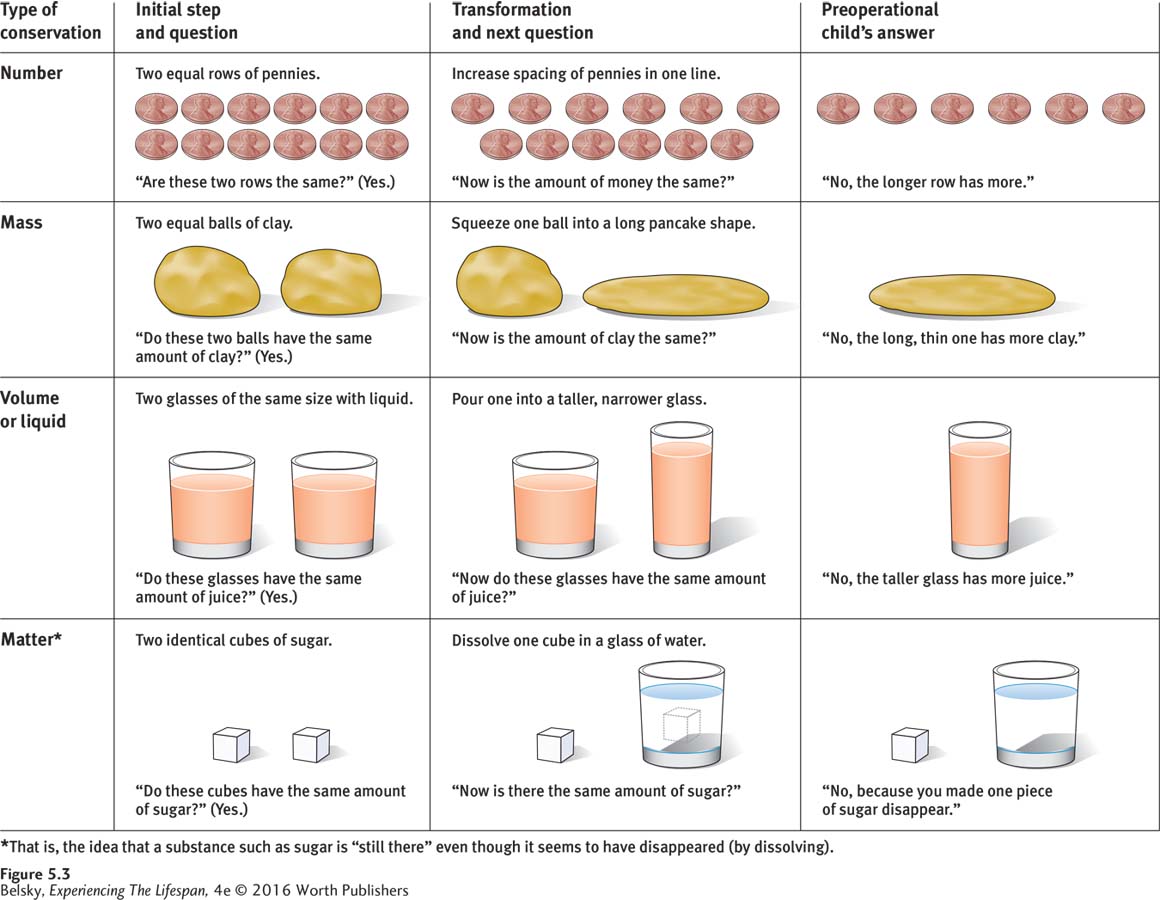

The fact that preoperational children are locked into immediate appearances is illustrated by Piaget’s (1965) famous conservation tasks. In Piaget’s terminology, conservation refers to knowing that the amount of a given substance remains identical despite changes in its shape or form.

In the conservation of mass task, for instance, an adult gives a child a round ball of clay and asks that boy or girl to make another ball “just as big and heavy.” Then she reshapes the ball so it looks like a pancake and asks, “Is there still the same amount now?” In the conservation of liquid task, the procedure is similar: present a child with two identical glasses with equal amounts of liquid. Make sure he tells you, “Yes, they have the same amount of water or juice.” Then, pour the liquid into a tall, thin glass while the child watches and ask, “Is there more or less juice now, or is there the same amount?”

Typically, when children under age 7 are asked this final question, they give a peculiar answer: “Now there is more clay” or “The tall glass has more juice.” “Why?” “Because now the pancake is bigger” or “The juice is taller.” Then, when the clay is remolded into a ball or the liquid poured into the original glass, they report: “Now it’s the same again.” The logical conflict in their statements doesn’t bother them at all. In Figure 5.3, I have illustrated these procedures as well as additional Piagetian conservation tasks to perform with children you know.

Why can’t young children conserve? For two reasons, Piaget believes. First, children don’t grasp a concept called reversibility. This is the idea that an operation (or procedure) can be repeated in the opposite direction. Adults accept the fact that we can change various substances, such as our hairstyle, or the color of our room, and reverse them to their original state. Young children lack this fundamental schema, or cognitive structure, for interpreting the world.

A second issue lies in a perceptual style that Piaget calls centering. Young children interpret things according to what first hits their eye, rather than taking in the entire visual array. In the conservation of liquid task, they become captivated by the height of the liquid. They don’t notice that the width of the original container makes up for the height of the current one. When children reach concrete operations, they decenter. They can step back from a substance’s immediate appearance and understand that an increase in one dimension makes up for a loss in the other one.

Centering—

144

This tendency to focus on immediate appearances explains why, in the opening chapter vignette, Moriah believed that Josiah had more paper when he cut his sheet into sections. Her attention was captured by the spread-

The idea that “bigger” automatically equals “more” extends to every aspect of preoperational thought. Ask a 3-

I was substitute teaching with a group of kindergarten children—

145

Peculiar Perceptions About People

Young children’s tendency to believe that “what hits my eye right now is real” explains why a 3-

I got insights into this identity constancy deficit at my son’s fifth birthday party, when I hired a “gorilla” to entertain the guests (some developmental psychologist!). As the hairy 6-

Animism refers to the difficulty young children have in sorting out what is really alive. Specifically, preschoolers see inanimate objects—

Listen to young children talking about nature, and you will hear delightful examples of animism: “The sun gets sleepy when I sleep.” “The moon likes to follow me in the car.” The practice of assigning human motivations to natural phenomena is not something we grow out of as adults. Think of the Greek thunder god Zeus, or the ancient Druids who worshiped the spirits that lived within trees. Throughout history, humans have regularly used animism to make sense of a frightening world.

A related concept is called artificialism. Young children believe that human beings have made everything in nature. Here is an example of this “daddy power” from Piaget’s 3-

L was in bed in the evening and it was still light: “Put the light out please” . . . (I switched the electric light off.) “It isn’t dark”—”But I can’t put the light out outside” . . . “Yes you can, you can make it dark.” . . . “How?” . . . “You must turn it out very hard. It’ll be dark and there will be little lights everywhere (stars).”

(Piaget, 1951/1962, p. 248)

146

Experiencing the Lifespan: Childhood Fears, Animism, and the Power of Stephen King

There was one shadow that would constantly cast itself on my bedroom wall. It looked just like a giant creeping towards me with a big knife in his hand.

I used to believe that Satan lived in my basement. The light switch was at the bottom of the steps, and whenever I switched off the light it was a mad dash to the top. I was so scared that Satan was going to stab my feet with knives.

Boy, do I remember the doll that sat on the top of my dresser. I called it “Chatty Kathy.” This doll came to life every night. She would stare at me, no matter where I went.

My mother used to take me when she went to clean house for Mrs. Handler, a rich lady. Mrs. Handler had this huge, shiny black grand piano, and I thought it came alive when I was not looking at it. It was so enormous, dark, and quiet. I remember pressing one of the bass keys, which sounded really deep and loud and it terrified me.

I remember being scared that there was something alive under my bed. I must tell you I sometimes still get scared that someone is under my bed and that they are going to grab me by my ankles. I don’t think I will ever grow out of this, as I am 26.

Can you relate to any of these childhood memories collected from my students? Perhaps your enemy was that evil creature lurking in your basement; the frightening stuffed animal on your wall; a huge object (with teeth) such as that piano; or your local garbage truck.

Now you know where that master storyteller Stephen King gets his ideas. King’s genius is that he taps into the preoperational thoughts that we have papered over, though not very well, as adults. When we read King’s story about a toy animal that clapped cymbals to signal someone’s imminent death, or about Christine, the car with a mind of its own, or about the laundry-

Animism and artificialism perfectly illustrate Piaget’s concept of assimilation. The child knows that she is alive and so applies her “alive” schema to every object. Having seen adults perform heroic physical feats, such as turning off lights and building houses, a 3-

The sun and moon examples illustrate another aspect of preoperational thought. According to Piaget, young children believe that they are the literal center of the universe, the pivot around which everything else revolves. Their worldview is characterized by egocentrism—

By egocentrism, Piaget does not mean that young children are vain or uncaring, although they will tell you they are the smartest people on earth and the activities of the heavenly bodies are at their beck and call. Many of their most loving acts show egocentrism. There is nothing more touching than a 3-

You can see delightful examples of egocentrism when having a conversation with a young child. Have you ever had a 3-

Piaget views egocentrism as a perfect example of centering in the human world. Young children are unable to decenter from their own mental processes. They don’t realize that what is in their mind is not in everyone else’s awareness, too.

The Concrete Operational Stage: Getting on the Adult Wavelength

Piaget discovered that the transition from preoperations to concrete operations happens gradually. First, children are preoperational in every area. Then, between ages 5 and 7, their thinking gets less static, or “thaws out” (Flavell, 1963). A 6-

147

By age 8, the child has reached this higher-

Piaget also found that specific conservations come in at different ages. First, children master conservation of number and then mass and liquid. They may not figure out the most difficult conservations until age 11 or 12. Imagine the challenge of understanding the last task in Figure 5.3 (see p. 144)—realizing that when sugar is dissolved in water, it exists, but in a molecular form.

Still, according to Piaget, age 8 is a landmark for looking beyond immediate appearances, for understanding seriation and categories, for decentering in the physical and social worlds, for abandoning the tooth fairy and the idea that our stuffed animals are alive, and for entering the planet of adults.

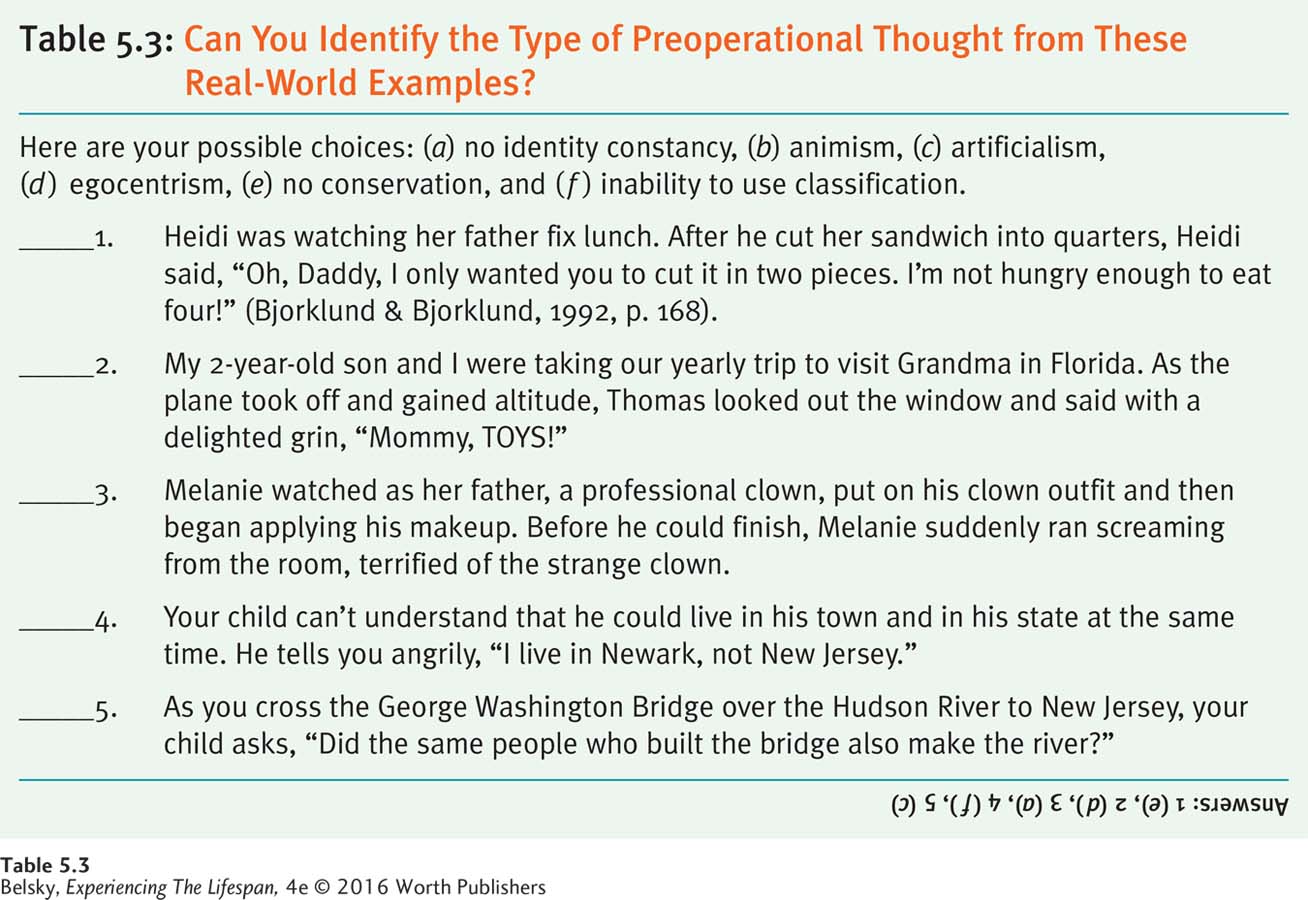

Table 5.3 shows examples of different kinds of preoperational ideas. Now, test yourself by seeing if you can classify each statement in Piagetian terms.

INTERVENTIONS: Using Piaget’s Ideas at Home and at Work

Piaget’s concepts provide marvelous insights into young children’s minds. For teachers, the theory explains why you need the same-

The theory makes sense of why forming a baseball team with a group of 4-

148

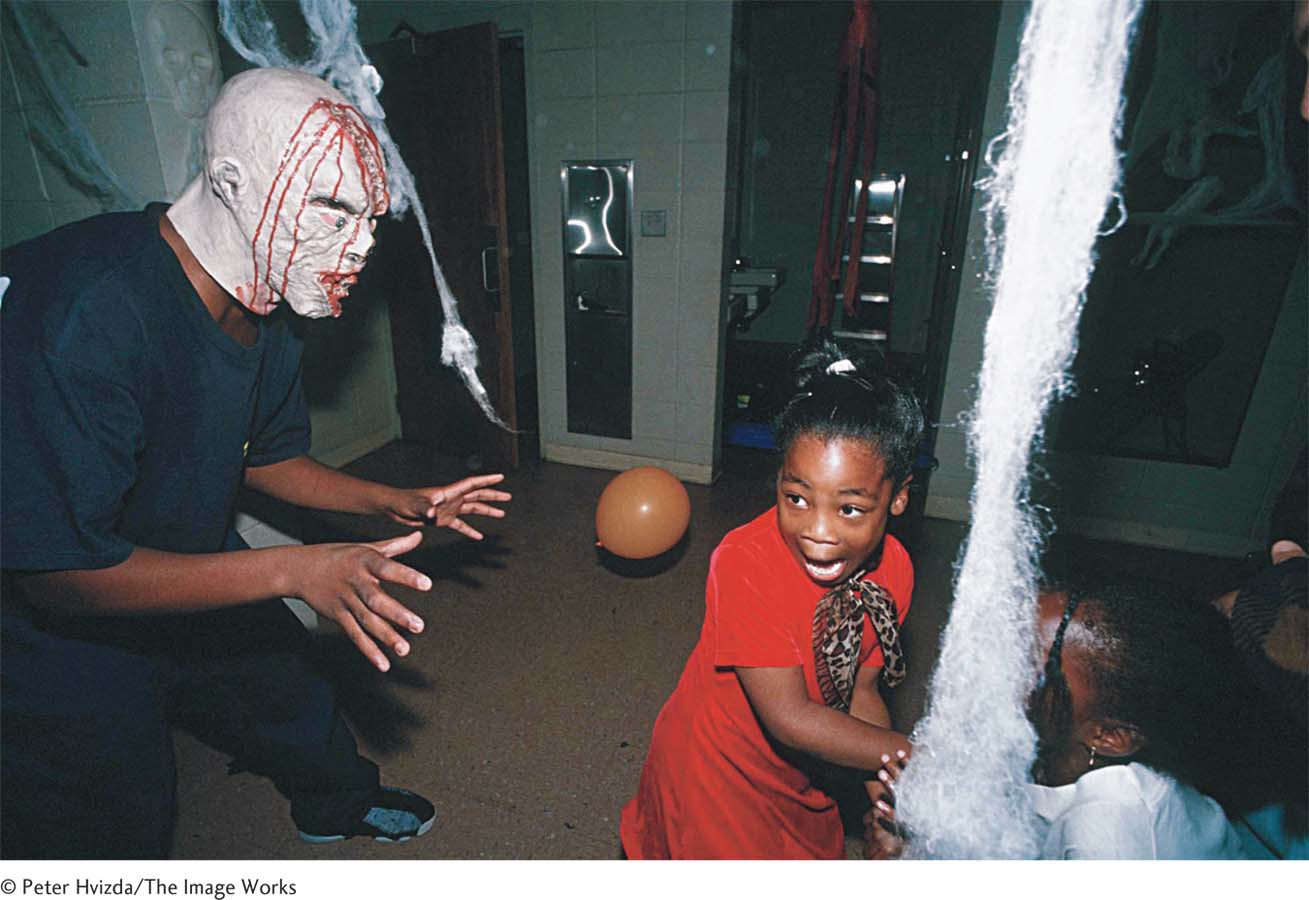

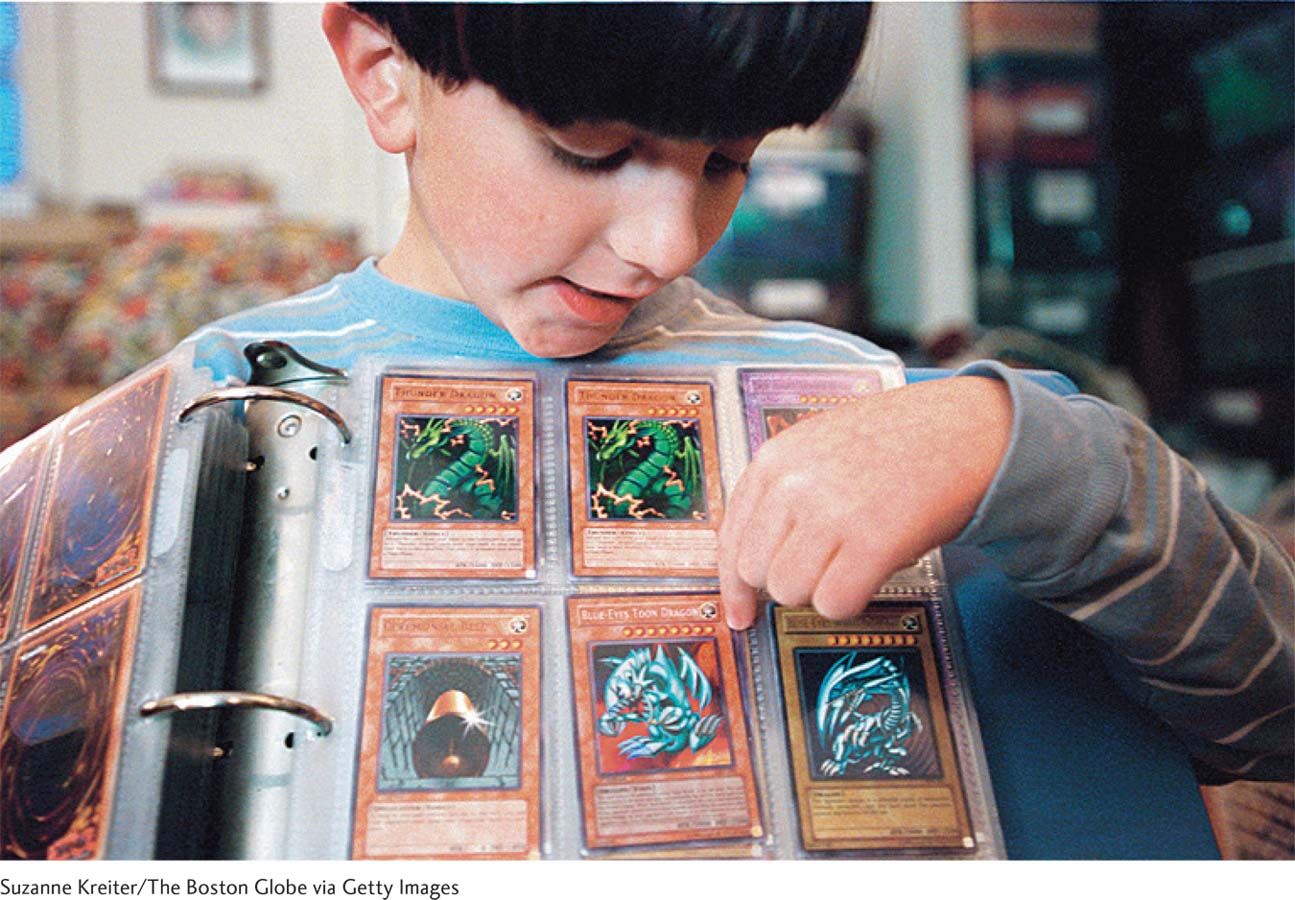

Piaget’s concepts also give us insights into children’s passions at different ages. They explain the power of pretending in early childhood (more about this in Chapter 6) and the lure of that favorite holiday, Halloween. When a 4-

The theory explains why “real school,” the academic part, fully begins at about age 7. Children younger than this age often don’t have the intellectual tools to understand reversibility, a concept critical to understanding mathematics (if 2 plus 4 is 6, then 6 minus 4 must equal 2). Even empathizing with the teacher’s agenda is a concrete operational skill.

The fact that age 8 is a coming-

Evaluating Piaget

Piaget has clearly transformed the way we think about young children. Still, as you saw with infancy, in important areas, Piaget was incorrect.

I described a major problem with Piaget’s ideas in Chapter 3: just as he minimized what babies know, Piaget underestimated preoperational children’s capacities. In particular, Piaget overstated young children’s egocentrism. If babies can decode intentions, the first awareness that we live in “different heads” must dawn on children at a far younger age than 8! (At the end of this chapter, you’ll learn when this mindreading ability fully comes on.)

We might also take issue with Piaget’s idea that we grow out of animism by age 8 or 9. Maybe he was giving us too much credit here. Do you have a good luck charm that keeps the plane from crashing, or a place you go for comfort where you can hear the trees whispering to you?

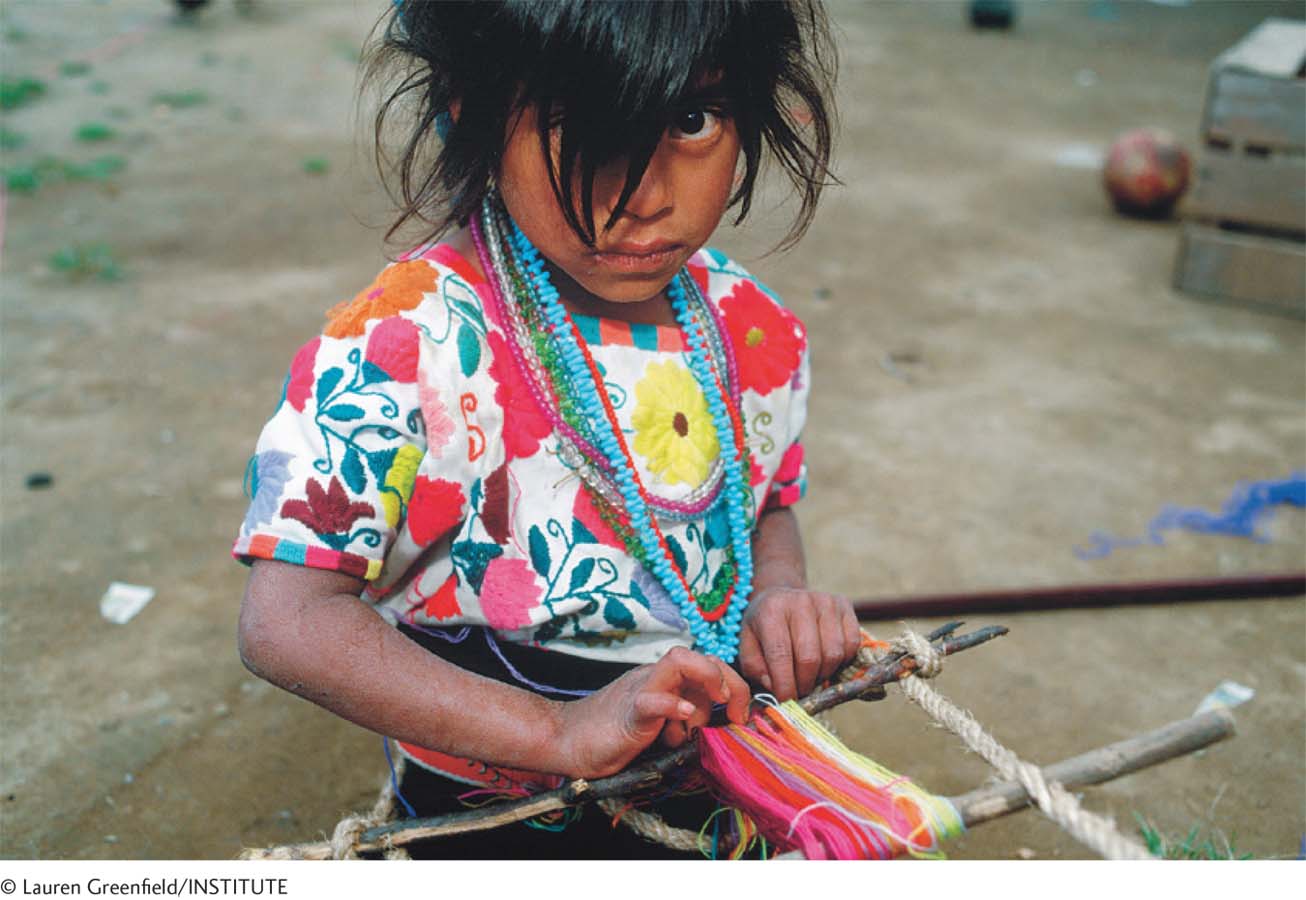

Children around the world do learn to conserve (Dasen, 1977, 1984). But because nature interacts with nurture, the ages at which they master specific conservation tasks vary from place to place. An example comes from a village in Mexico, where weaving is the main occupation. Young children in this collectivist culture grasp conservation tasks involving spatial concepts when they are younger than age 7 or 8 because they have so much hands-

149

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development

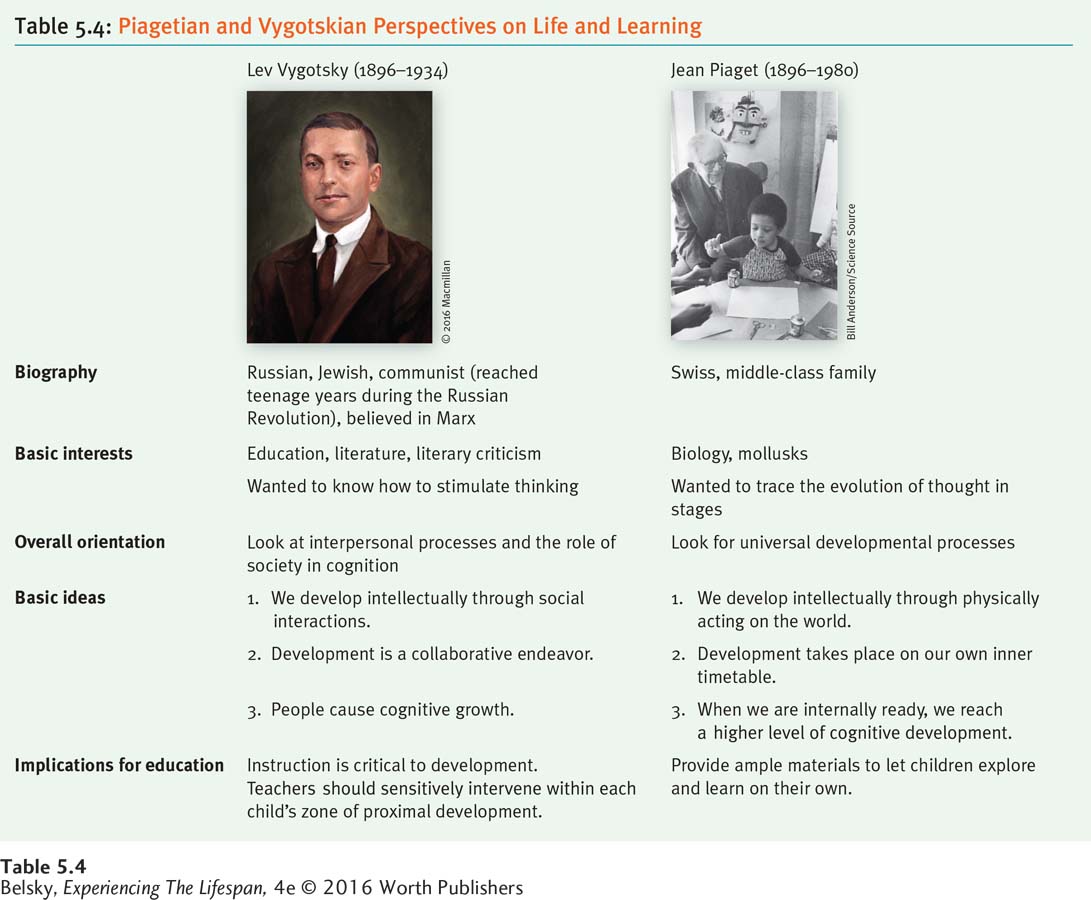

Piaget implies that children naturally construct an adult view of the world. We can’t convince preschoolers that their dolls are not alive or that the width of the glass makes up for the height. They must grow out of those ideas on their own. The Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1962, 1978) had a different perspective: people propel mental growth.

Vygotsky was born in the same year as Piaget. He showed as much brilliance at a young age, but—

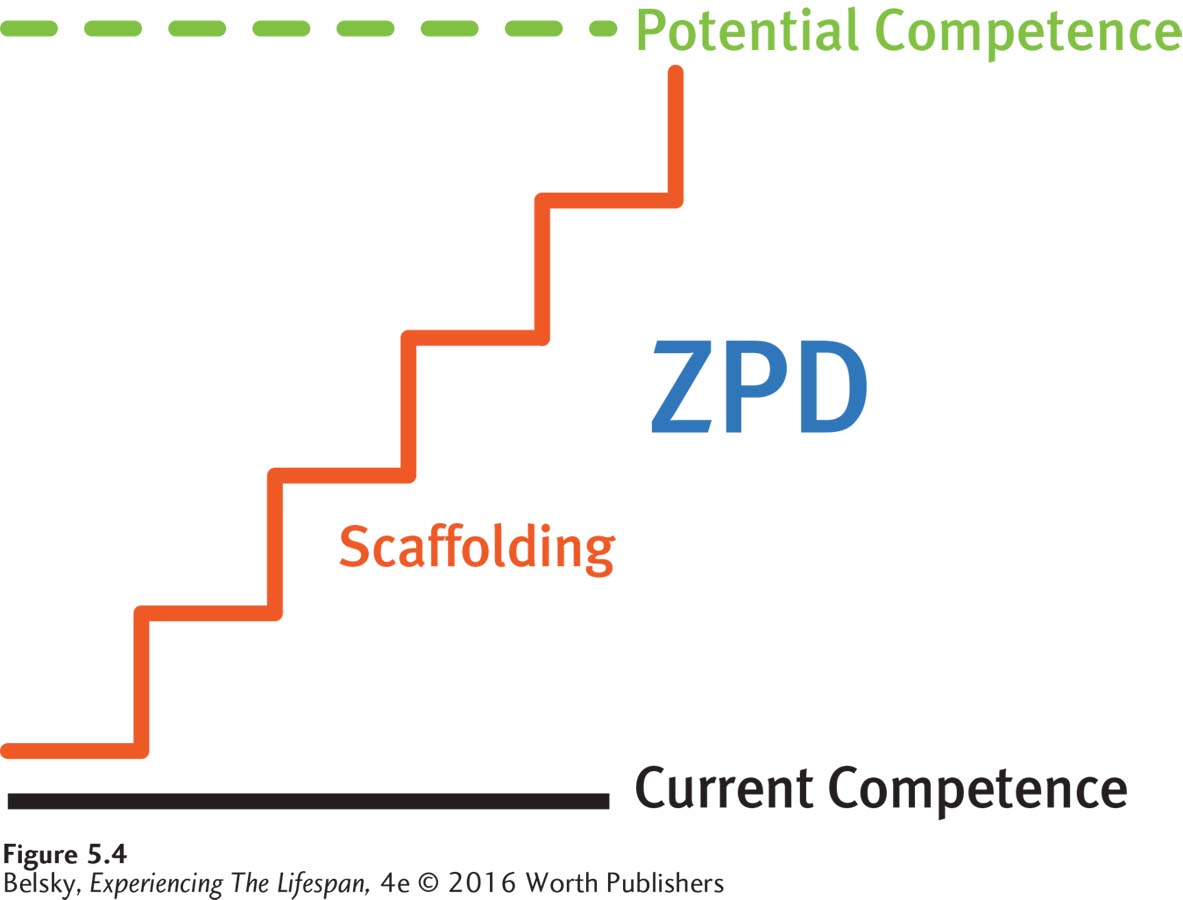

Vygotsky theorized that learning takes place within the zone of proximal development, which he defined as the difference between what the child can do by himself and his level of “potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86; also, see the diagram in Figure 5.4). Teachers must tailor their instruction to a child’s proximal zone. Then, as that child becomes more competent, they should slowly back off and allow the student more responsibility for directing that learning activity on his own. This sensitive pacing has a special name: scaffolding (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976).

You saw scaffolding in operation in Chapter 3 in my discussion of infant-

Tiffany threw the dice, then looked up at her mother. Her mother said, “How many is that?” Tiffany shrugged her shoulders. Her mother said, “Count them,” but Tiffany just sat and stared. Her mother counted the dots aloud, and then said to her daughter, “Now you count them,” which Tiffany did. This was repeated for the next five turns. Tiffany waited for her mother to count the dots. On her sixth move, however, Tiffany counted the dots on the dice on her own after her mother’s request. . . . Eventually, Tiffany threw the dice and counted the dots herself and continued to do so, practicing counting and moving the pieces on both her own and her mother’s turns.

(Bjorklund & Rosenblum, 2001)

Notice that this mother was a superb scaffolder. By pacing her interventions to Tiffany’s capacities, she paved the way for her child to master the game. But this process did not just flow from parent to child. Tiffany was also teaching her mother how to respond. Just as your professor is getting new insights into lifespan development while teaching every class—

In our culture, we have definite ideas about what makes a good scaffolder. Enter a child’s proximal zone. Actively instruct, but be sensitive to a child’s responses. However, in collectivist societies, such as among the Mayans living in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, children learn by observation. They listen. They watch. They are not explicitly taught the skills they need for adult life (Rogoff and others, 2003). So the qualities our culture sees as vital to socializing children are not necessarily part of the ideology of good parenting around the globe.

150

INTERVENTIONS: Becoming an Effective Scaffolder

In our teaching-

They foster a secure attachment, as nurturing, responsive interactions are a basic foundation for learning (Laible, 2004).

They break a larger cognitive challenge, such as learning Chutes and Ladders, into manageable steps (Berk & Winsler, 1999).

They continue helping until the child has fully mastered the concept before moving on, as Tiffany’s mother did earlier.

As you will learn in Chapter 7, these same scaffolding principles—

Table 5.4 compares Vygotsky’s and Piaget’s perspectives and offers capsule summaries of the backgrounds that shaped these world-

151

The Information-

Vygotsky filled in the missing social pieces of Piaget’s theory and gave us a framework for stimulating mental growth. But he did not address the gaps in the theory itself. Why are children able to decenter? What specific skills allow children to understand that the width of the glass makes up for the height?

Piaget never mentions how crucial abilities such as memory, concentration, and planning develop. Was Ms. Angela, the teacher in the opening chapter vignette, asking too much of her 3-

Information-

Making Sense of Memory

Information-

Working memory is where the “cognitive action” takes place. Here, we keep information in awareness and act to either process it or discard it. Working memory is made up of limited-

You can get a real-

Just as they vary in motor talents, young children differ in working memory abilities, and these differences predict school readiness skills (Fizpatrick & Pagani, 2012; Preßler, Krajewski, & Hasselhorn, 2013). Moreover, while the basic structure of working memory, described above, swings into operation by about age 6 (Michalczyk and others, 2013), this capacity enlarges dramatically during elementary school (Alloway & Alloway, 2013; Thaler and others, 2013). Actually, the fact that memory-

Exploring Executive Functions

Executive functions refer to any skill related to managing our memory, controlling our cognitions, planning our behavior, and inhibiting our responses. Executive functions depend on the brain’s master planner—

152

Older Children Rehearse Information

A major way we learn information is through rehearsal. We repeat material to embed it in memory. In a classic study, developmentalists had kindergarteners, second graders, and fifth graders memorize objects (such as a cat or a desk) pictured on cards (Flavell, Beach, & Chinsky, 1966). Prior to the testing, the research team watched the children’s lips to see if they were repeating the names of the objects to themselves. Eighty-

Older Children Understand How to Selectively Attend

The ability to manage our awareness so we focus on what we need to know and filter out extraneous information is called selective attention. In a classic study illustrating young children’s problems in this area, researchers presented boys and girls of different ages with cards. On one half of each card was an animal photo; on the other half was a picture of some household item (see Figure 5.5). The children were instructed to remember only the animals.

As you might expect, older children were better at recalling the animal names. But now comes the interesting part: when the children were asked how many irrelevant items they could recall, the performance differences evaporated—

Older Children Are Superior at Inhibition

Turn back to the vignette at the beginning of this chapter to see the problems young children have inhibiting their impulses. Notice how the 3-

To measure differences in inhibition directly, researchers may ask children to perform some action that contradicts their immediate tendencies, such as instructing them to say the word black when they see the word white (Diamond, Kirkham, & Amso, 2002). Or the child may be instructed, “Press a button as fast as you can each time you see an animal on the screen, but don’t respond when you see a dog” (Pnevmatikos & Trikkaliotis, 2013). This “go, don’t go” challenge is exemplified by the classic childhood game Simon Says.

153

Performance on these tasks improves markedly during preschool, and gradually gets better with age (Best & Miller, 2010). Actually, fostering inhibition—

Moreover, if you think these self-

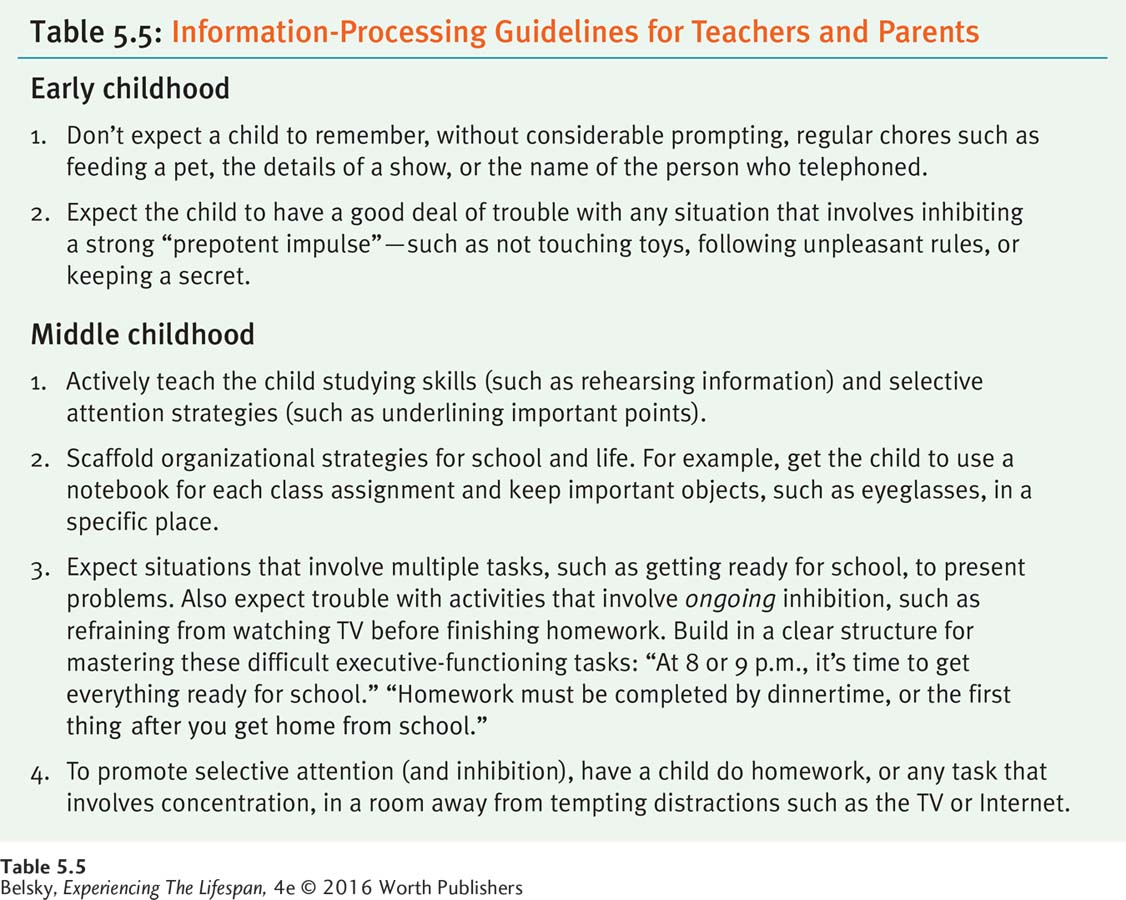

INTERVENTIONS: Using Information-Processing Theory at Home and at Work

So, to return to the beginning of this section, teachers cannot assume that third graders will automatically understand how to memorize spelling words. Scaffolding study skills, such as the need to rehearse, or teaching strategies to promote selective attention, such as putting large stars next to the relevant words for a test, should be an integral part of education, beginning in elementary school.

Parents will probably need to regularly remind a child, even at age 6 or 7, to feed the dog. Expect activities requiring different information-

Now that we know how thinking normally develops, let’s look at the insights information-

154

Hot in Developmental Science: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention-

ADHD follows a bewildering array of paths: from first appearing in preschool, to erupting during adulthood; from persisting for decades, to fading after months (Sonuga-

ADHD has been linked to everything from prenatal maternal smoking, to breathing problems at birth (Owens & Hinshaw, 2013). One widely accepted idea is that this condition results from a lower-

The hallmark of ADHD, however, is deficits in executive functions (Halperin & Healey, 2011). These children have problems with working memory (Alderson and others, 2013; Dovis and others, 2013) and especially inhibition (Barkley, 1998, 2003; Berger and others, 2013). When told, “Don’t touch the toys,” boys and girls diagnosed with ADHD have special trouble resisting this impulse.

These children also have difficulties with selective attention. Researchers asked elementary schoolers to memorize a series of words. Some words were more valuable to remember (that is, worth more points), and others less. Boys and girls with ADHD memorized an equal number of words as a comparison group; but, like the preschoolers in the previous section, they got lower scores because they clogged their memory bins with less valuable words (Castel and others, 2010).

As you might imagine, performing a sequence of tasks under time pressure, such as getting ready for school by 7:00 a.m., presents immense problems for boys and girls with ADHD. These children have more trouble estimating time (Gooch, Snowling, & Hulme, 2011; Hurks & Hendriksen, 2011; Hwang and others, 2010). Moreover, perhaps because of their dopamine deficit, they seem less affected by punishments and rewards (Stark and others, 2011). So, yelling, or threatening, simply may not work.

These issues explain why school is so problematic for boys and girls with ADHD. Working memory is critical to performing any academic task. Focusing on a teacher demands inhibitory and selective attention skills. Taking tests can involve exceptional time-

Because the same difficulties lead to problems at home, frustrated parents are apt to resort to power-

155

Frequent social failures seem to be most upsetting for girls (Becker and others, 2013). Anxiety—

INTERVENTIONS: Helping Children with ADHD

The well-

Parent training often takes a behavioral approach by teaching adults to target upsetting behaviors (rather than ineffectually yelling), pay attention to positive acts, consistently use time out, and offer children concrete rewards for behaving (Ryan-

Another strategy focuses on helping children enhance working memory, attention, and inhibition. And then there are interventions focused on diet—

One summary of the incredible 2,000-

What does work? Children with ADHD learn better in noisy environments. So, to enhance a 9-

Students have told me that getting absorbed in high-

156

But perhaps some brains don’t need mending. ADHD symptoms appear on a continuum (Bell, 2011; Larsson and others, 2012). Where should we really put the cutting point between normal childhood inattentiveness and a diagnosed “disease”? The dramatic early-

Wrapping Up Cognition

Now that I have reached the end of our survey of cognition, it should be clear why our species needs a decade (or two) beyond infancy to master the intellectual challenges of the adult world. Now, imagine the insights we would be missing if we left out any theory. What if you wanted to make sense of the strange ideas preschoolers have, or needed a general strategy for stimulating intellectual growth, or were looking for guidance about what to expect from children in terms of listening, following directions, and sitting still? You would have to turn to Piaget, Vygotsky, and the information-

Tying It All Together

Question 5.9

While with your 3-

Mark tells you that the big tree in the garden is watching him.

When you stub your toe, Mark gives you his favorite stuffed animal.

Mark tells you that his daddy made the sun.

Mark says, “There’s more now,” when you pour juice from a wide carton into a skinny glass.

Mark tells you that his sister turned into a princess yesterday when she put on a costume.

(a) animism; (b) egocentrism; (c) artificialism; (d) can’t conserve; (e) (no) identity constancy

Question 5.10

In a sentence, explain the basic mental difference between an 8-

Children in concrete operations can step back from their current perceptions and think conceptually, while preoperational children can’t go beyond how things immediately appear.

Question 5.11

Four-

Buy Chris easy-

Question 5.12

Turn back to the opening chapter vignette on page 135. List three activities specifically tailored to help train these preschoolers in the skills of regulating and inhibiting their responses.

(1) Following the play center rules to clean up, not take toys outside, and keep oneself from entering if there are four children; (2) having the class sit still and raise their hands to speak; (3) the dance slower and faster activity.

Question 5.13

Laura’s son has been diagnosed with ADHD. Based on this chapter, suggest some environmental strategies she might use to help her child.

Don’t put your son in demanding situations involving time management. When he studies, provide “white” background noise. Use small immediate reinforcers, such as prizes for good behavior that day. Get your son involved in sports or playing exciting games. Avoid power assertion (yelling and screaming), and go out of your way to provide lots of love.