5.4 Language

157

So far, I have been discussing the cognitive and physical milestones in this chapter as if they occurred in a vacuum. But, as I highlighted at the beginning of this chapter, that uniquely human skill, language, is vital to every childhood advance. Vygotsky (1978) actually put language—

Inner Speech

According to Vygotsky, learning takes place when the words a child hears from parents and other scaffolders migrate inward to become talk directed at the self. For instance, using the earlier example of Chutes and Ladders, after listening to her mother say “Count them” a number of times, Tiffany learned the game by repeating “Count them” to herself. Thinking, according to Vygotsky, is inner speech.

Support for this idea comes from listening to young children monitor their actions. A 3-

Developing Speech

How does language itself unfold? Actually, during early childhood language does more than unfold. It explodes.

By our second birthday, we are just beginning to put together words (see Chapter 3). By kindergarten, we basically have adult language nailed down. When we look at the challenges involved in mastering language, this achievement becomes more remarkable. To speak like adults, children must articulate word sounds. They must string units of meaning together in sentences. They must produce sentences that are grammatically correct. They must understand the meanings of words.

The word sounds of language are called phonemes. When children begin to speak in late infancy, they can only form single phonemes—

The meaning units of language are called morphemes (for example, the word boys has two units of meaning: boy and the plural suffix s). As children get older, their average number of morphemes per sentence—

This brings up the steps to mastering grammar, or syntax. What’s interesting here are the classic mistakes that young children make. As parents are aware, one of the first words that children utter is no. First, children typically add this word to the beginning of a sentence (“No eat cheese” or “No go inside”). Next, they move the negative term inside the sentence, next to the main verb (“I no sing” or “He no do it”). A question starts out as a declarative sentence with a rising intonation: “I have a drink, Daddy?” Then it, too, is replaced by the correct word order: “Can I have a drink, Daddy?” Children typically produce grammatically correct sentences by the time they enter school.

158

The most amazing changes occur in semantics—

One mistake young children make while learning language is called overregularization. Around age 3 or 4, they often misapply general rules for plurals or past tense forms even when exceptions occur. A preschooler will say runned, goed, teached, sawed, mouses, feets, and cup of sugars rather than using the correct irregular form (Berko, 1958).

Another error lies in children’s semantic mistakes. Also around age 3, children often use overextensions—

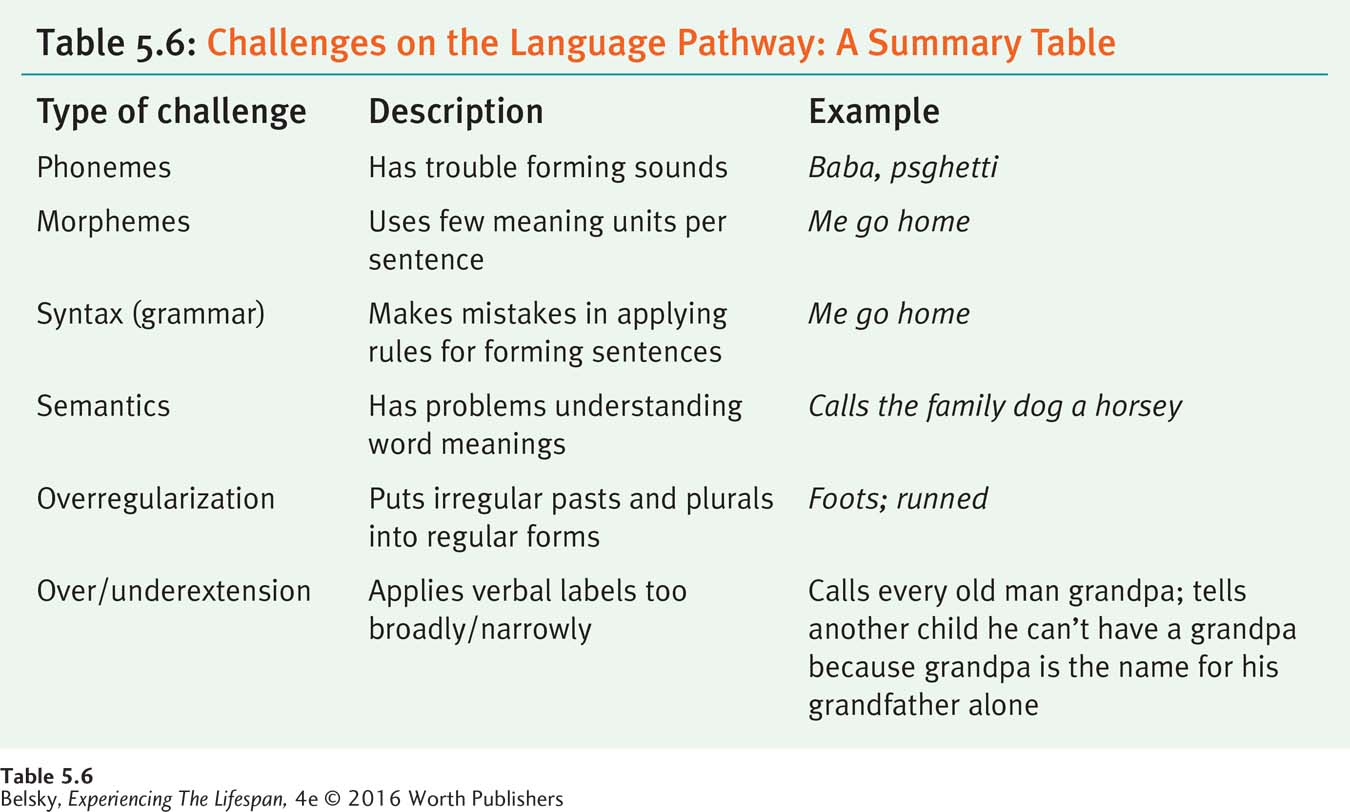

Table 5.6 summarizes these challenges. Now you might want to have a conversation with a 3-

Tying It All Together

Question 5.14

A 5-

Vygotsky would say it’s normal—

Question 5.15

You are listening to a 3-

When offered a piece of cheese, Joshua said, “I no eat cheese.”

Seeing a dog run away, Joshua said, “The doggie runned away.”

Taken to a petting zoo, Joshua pointed excitedly at a goat and said, “Horsey!”

(b) = overregularization; (c) = overextension

159