6.2 Personality (and the Emerging Self)

As they get older, how do children’s perceptions about themselves change and how do these changes affect self-

Observing the Self

Developmentalist Susan Harter (1999) has explored the first questions in her research program examining how children view themselves. To make sense of her findings, Harter draws on Piaget’s distinction between preoperational and concrete operational thinking—

171

Children in the concrete operational stage:

Look beyond immediate appearances and think abstractly about inner states.

Give up their egocentrism and realize they are but one person among many others in this vast world.

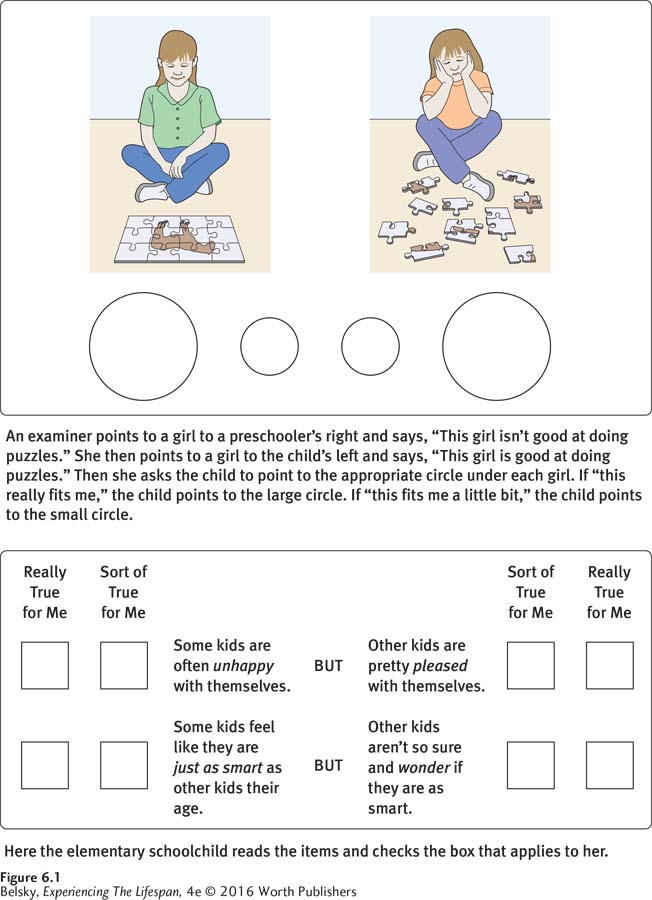

To examine how these changes affect self-

I am 3 years old and I live in a big house. . . . I have blue eyes and a kitty that is orange. . . . I love my dog Skipper. . . . I’m always happy. I have brown hair. . . . I’m really strong.

I’m in fourth grade, and I’m pretty popular. . . .That’s because I’m nice to people . . . , although if I get into a bad mood I sometimes say something that can be a little mean. At school I’m feeling pretty smart in . . . Language Arts and Social Studies. . . . But I’m feeling pretty dumb in Math and Science. . . .

(adapted from Harter, 1999, pp. 37, 48)

Notice that the 3-

Actually, studies around the world show that self-

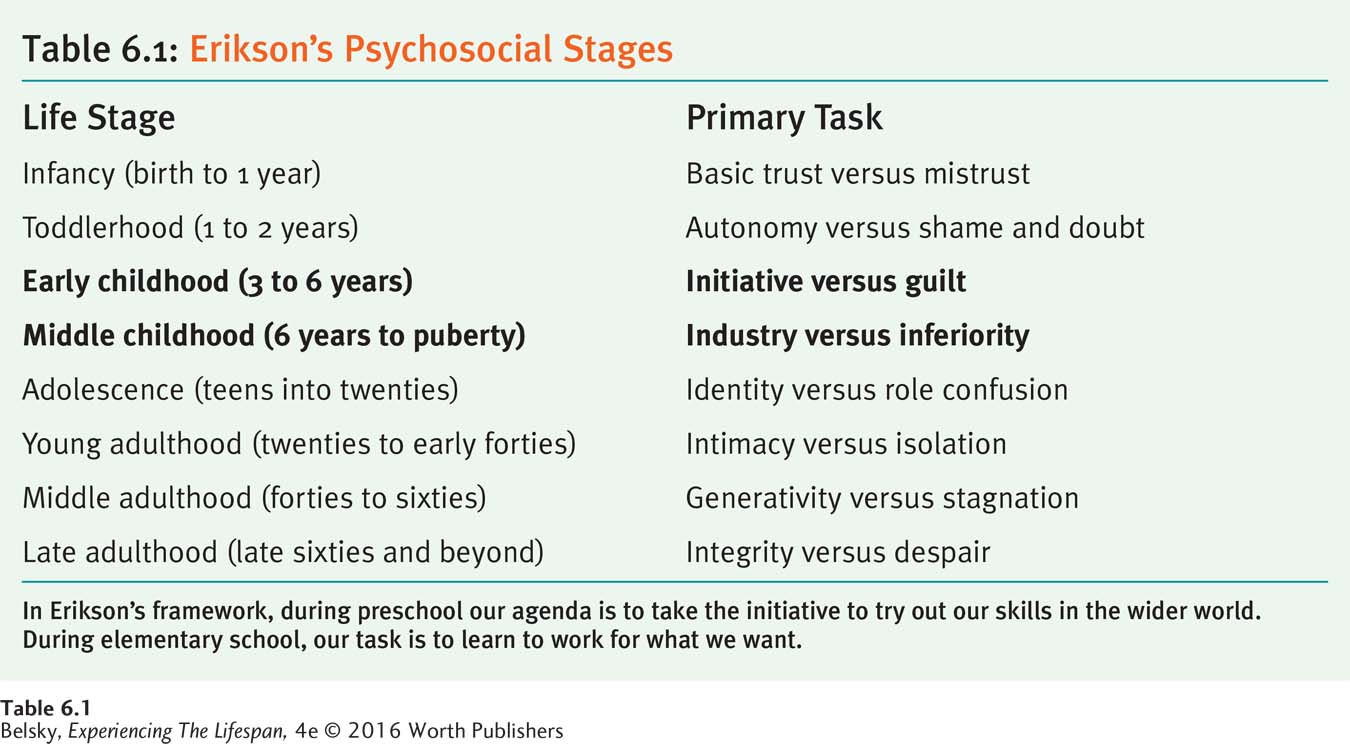

Harter’s research beautifully dovetails with Erik Erikson’s early and middle childhood developmental tasks. Erikson, as you can see in Table 6.1, labeled the preschool psychosocial challenge as initiative versus guilt. Children’s mission at this age, he believed, is to courageously test their abilities in the wider world. From risking racing your tricycle in the street to scaling the school monkey bars, our challenge in early childhood is taking the initiative to confront life.

172

In middle childhood (from age 6 to 12) our task shifts to industry versus inferiority— the need to manage our emotions and work for what we want to achieve (industry). Now we know that we are not just wonderful, and are vulnerable to low self-

Still, all is not lost because this new, realistic understanding produces another change. Notice how the fourth grader on page 171 compares her abilities in different areas such as personality and school. As they get older, this means children’s self-

According to Harter, children draw on five areas to determine their self-

As you might expect, children who view themselves as “not so good” in several domains often report low self-

To understand this point, take a minute to rate yourself in your people skills, politeness or good manners, your intellectual abilities, looks, and your physical abilities. If you label yourself “not so good” in an area you don’t care about (for me, it would be physical skills), it won’t make a dent in your self-

This discounting process (“It doesn’t matter if I’m not a scholar; I have great relationship skills”) is vital. It lets us gain self-

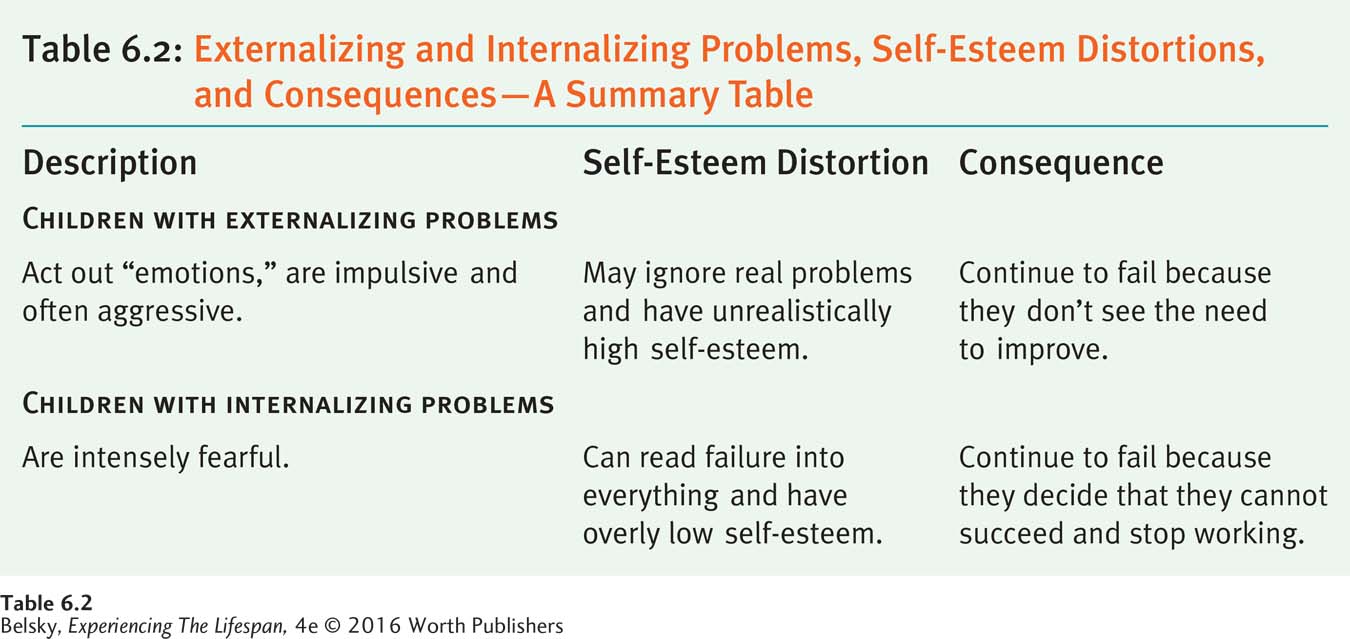

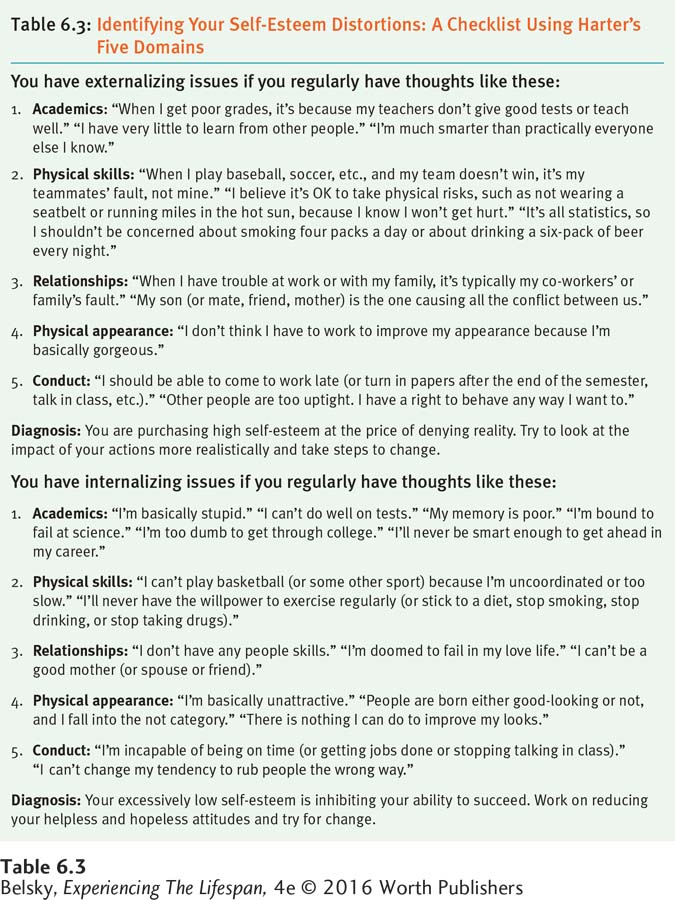

Two Kinds of Self-

Normally, we base our self-

Children with internalizing tendencies have the opposite problem. Their hypersensitivity to environmental cues (recall Chapter 4) may cause them to read failure into benign events. (“My teacher hates me because she looked at me the wrong way.”) They are at risk of developing learned helplessness (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978), the feeling that they are powerless to affect their fate. They give up at the starting gate, assuming, “I know I’m going to fail, so why should I try?”

So, children and adults with externalizing and internalizing tendencies face a similar danger—

173

Table 6.2 summarizes these self-

174

INTERVENTIONS: Promoting Realistic Self-Esteem

This discussion shows why school programs focused just on raising self-

ENHANCING SELF-

175

You might think that praising kids for effort would only be effective when children have reached concrete operations and developed fixed ideas about the self (“I am basically dumb”). But when researchers videotaped mothers’ interactions with their 2-

ENCOURAGING ACCURATE PERCEPTIONS. Still, if a child—

There is a way of softening this painful “You are not doing so well” message that is the price of realistically seeing the self. Harter (1999, 2006) finds that feeling loved by their attachment figures provides a cushion when children understand they are having trouble in an important area of life. So, returning to the beginning of this section, school programs (and adults) that stress the message “I care about you,” plus foster self-

Doing Good: Prosocial Behavior

On the morning of September 11, 2001, the nation was riveted by the heroism of the firefighters who ran into the World Trade Center buildings, risking almost certain death. We marveled at the “ordinary people” working in the Twin Towers, whose response to this emergency was to help others get out first.

Prosocial behavior is the term developmentalists use to describe such amazing acts of self-

The answer is no. Each prosocial activity naturally appears early in life (Hepach, Vaish, & Tomasello, 2013; Thompson & Newton, 2013). Toddlers will help a researcher retrieve an out-

This impetus to help, comfort, and share, which blossoms during toddlerhood, appears in cultures around the world (House and others, 2013). Moreover, doing good makes young children feel good. Toddlers look happier after giving a treat to another person than when they get that treat for themselves. They seem especially joyous when engaging in costly giving—

176

Individual and Gender Variations

However, as you saw in the vignette at the beginning of the chapter, children differ in the strength of this impulse to help, comfort, and spontaneously share. Developmentalists visited preschool classrooms and looked specifically at spontaneous sharing, the coming-

What about your 4-

Decoding Prosocial Behavior in a Deeper Way

Empathy is the term developmentalists use for directly feeling another person’s emotion. You get anxious when you hear your boss berating a co-

Sympathy is the more muted feeling that we experience for another human being. You feel terrible for your co-

The reason is that experiencing another person’s distress can provoke a variety of reactions, from becoming immobilized with fear to behaving in a far-

Acting prosocial, especially after preschool, also requires superior information processing skills. You need to decide when to be generous, which explains why 2-

177

Returning to gender differences, this suggests we take a more nuanced approach to the idea that females are more (or less) prosocial than males. Yes, women qualify as more prosocial if we measure comforting someone in emotional pain. Men, however, may be more prosocial in their own competence realm—

Finally, people are more apt to reach out prosocially when they are happy—

To summarize, the impulse to share, to help, and to comfort is built into our species. But to predict who acts on that impulse, we need to ask specific questions: “Does this child have good executive functions?” “Does he have the concrete skills to help?” “Is she a confident, upbeat human being?”

Now that we’ve targeted the qualities involved in being prosocial, what can adults do to encourage these behaviors in a child?

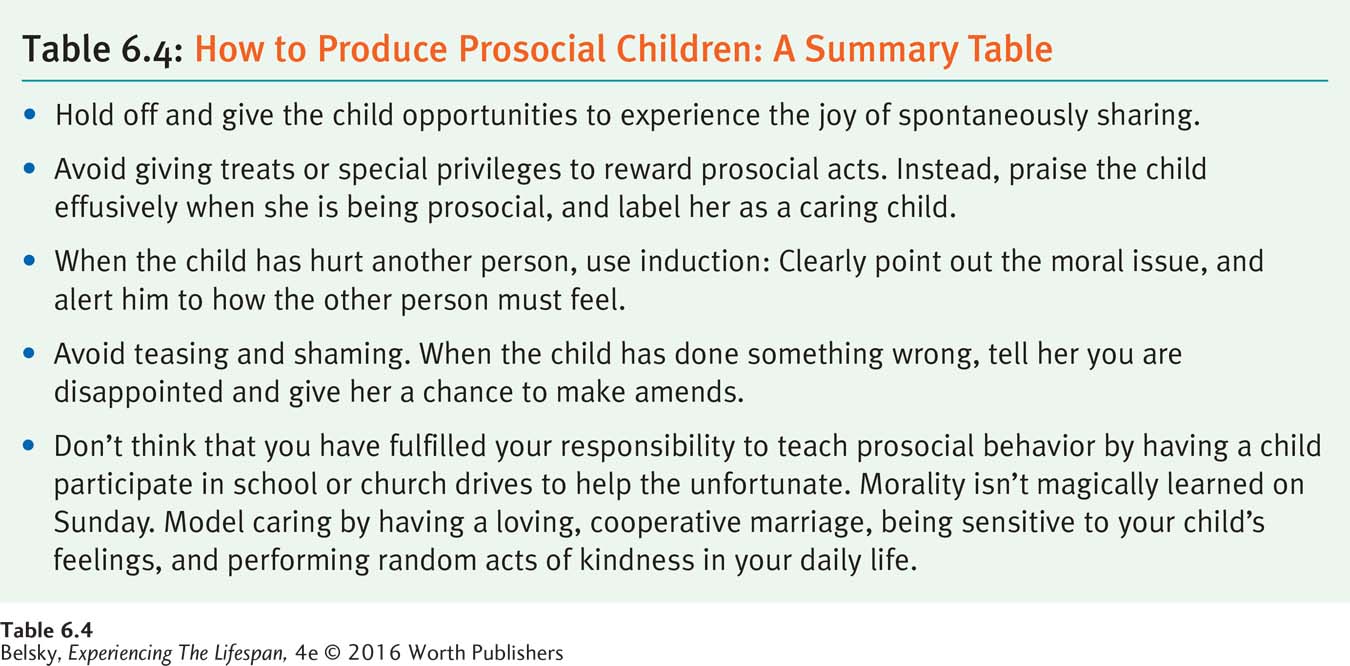

INTERVENTIONS: Socializing Prosocial Children

As some of you might imagine, offering concrete reinforcements, such as giving prizes for sharing, is counterproductive. External reinforcers undercut the happiness that flows from spontaneously performing costly prosocial acts. In one fascinating study, children who had earlier been given the chance to make a difficult prosocial decision—

Providing a caring socialization climate is important. Model prosocial behavior, making sure your toddler sees you regularly help people in need (Williamson, Donohue, & Tully, 2013). Behave in a caring, cooperative way with your spouse (Scrimgeour and others, 2013). Encourage a young child to talk about her emotions, and respond to her distress in a sympathetic way (Taylor and others, 2013). Be attuned to the caring things that your child does and attribute them to her personality—

Most studies of prosocial behavior focus on a socialization technique called induction (Hoffman, 1994, 2001). Caregivers who use induction point out the ethical issues when a child has performed a hurtful act. Now, imagine that classic situation when your 8-

Induction has several virtues: It offers children concrete feedback about exactly what they did wrong and moves them off of focusing on their own punishment (“Now, I’m really going to get it!”) to the other child’s distress (“Oh, gosh, she must feel hurt”). Induction also allows for reparations, the chance to make amends. Induction works because it stimulates the emotion called guilt.

178

Shame Versus Guilt and Prosocial Acts

Think back to an event during childhood when you felt terrible about yourself. Perhaps it was the day you were caught cheating and sent to the principal. What you may remember was feeling so ashamed. Developmentalists, however, distinguish between feeling ashamed and experiencing guilt. Shame is the primitive feeling we have when we are personally humiliated. Guilt is the more sophisticated emotion we experience when we have violated a personal moral standard or hurt another human being.

I believe that Erikson may have been alluding to this maturity difference when he labeled “shame” as the emotion we experience as toddlers, and reserved “guilt” for the feeling that arises during preschool, when our drive to master the world causes other people distress (see Table 6.1 on page 171). While shame and guilt are both “self-

This suggests that socialization techniques involving shame are especially poisonous. If, when you arrived at the principal’s office, he shamed you (“In the next school assembly, I’ll announce what a terrible person you are!”), you might change your behavior, but at an emotional price. You would feel humiliated. You might decide you hated school. But if the principal induced guilt (“I feel disappointed because you’re such a good kid”), you could act to enhance self-

Table 6.4 summarizes these section messages and offers an additional tip. And, for readers who are thinking, “I’m prosocial, even though I didn’t grow up in that kind of home,” there is the reality that people can draw on shaming childhood experiences to construct prosocial lives. Perhaps you have a friend who grew up in an abusive family whose mission it is to work with abused children or (like me) have been privileged to meet childhood survivors of Hitler’s holocaust who have devoted their lives to teaching people “never again!” Then you will realize that, while love is the best prosocial socializer, life’s adversities can promote exceptional altruism, too (more about this compelling topic in Chapter 12).

Now that we have analyzed what makes us do good (the angel side of personality), let’s enter the darker side of human nature: aggression.

179

Doing Harm: Aggression

Aggression refers to acts designed to cause harm, from shaming to shoving, from gossiping to starting unprovoked wars. It should come as no surprise that physical aggression reaches its life peak at around age 2 1/2 (Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006; van Aken and others, 2008). During this critical age for socialization, children are vigorously being disciplined but don’t have the capacity to inhibit their responses. Imagine being a toddler continually ordered by giants to do impossible things, such as sharing and sitting still. Because being frustrated provokes aggression, it makes perfect sense that hitting and throwing tantrums are normal during “the terrible twos.”

As preschoolers become more skilled at regulating their emotions and can make better sense of adults’ rules, rates of open aggression (yelling or hitting) dramatically decline (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011). As children get older, the reasons for aggression change. Preschool fights center on objects, such as toys. During elementary school, when children have developed a full-

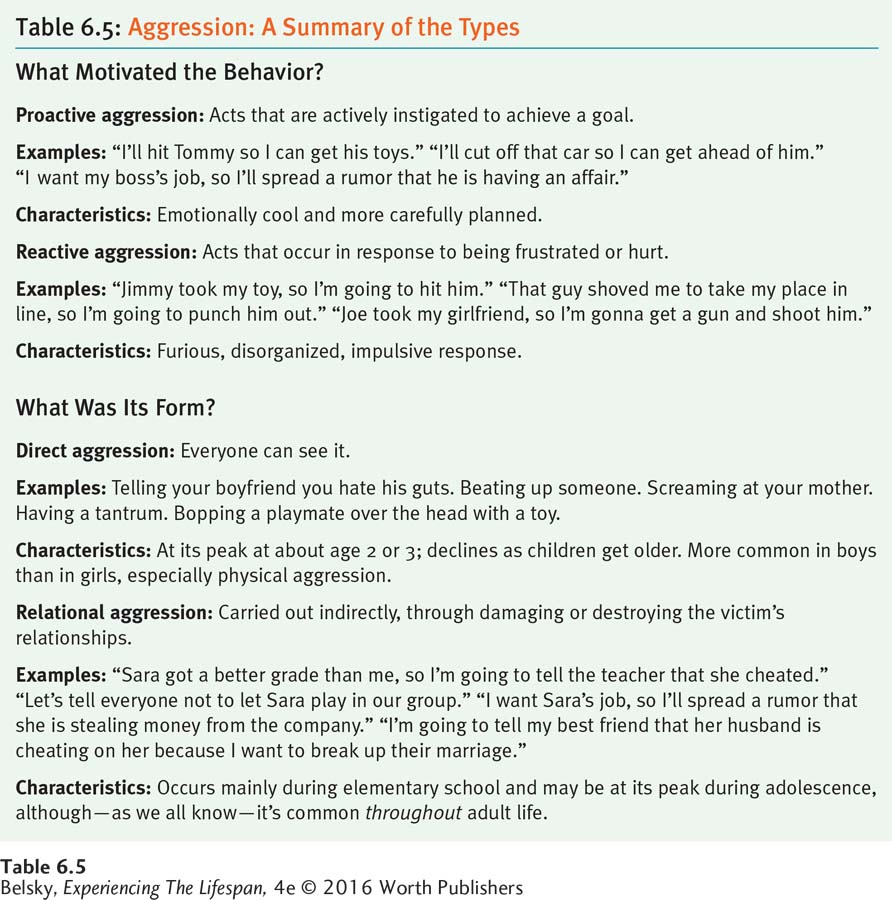

Types of Aggression

One way developmentalists classify aggression is by its motive. Proactive aggression refers to hurtful behavior that is initiated to achieve a goal. Johnny kicks Manuel to gain possession of the block pile. Sally spreads a rumor about Moriah to replace her as Sara’s best friend. Reactive aggression occurs in response to being hurt, threatened, or deprived. Manuel, infuriated at Johnny, kicks him back.

Its self-

This feeling is normal. According to a classic theory called the frustration-

In addition to its motive—

Because it targets self-

Most of us assume relational aggression is more common in girls, but, in research, this “obvious” gender difference does not appear. Yes, overt aggression is severely sanctioned in females, so girls make relational aggression their major mode (Ostrov & Godleski, 2010; Smith, Rose, & Schwartz-

180

Table 6.5 summarizes the different types of aggression and gives examples from childhood and adult life. While scanning the table, notice that we all behave in every aggressive way. Also, being aggressive is not “bad.” As I just implied, it is vital to making our way in the world. Children who are popular don’t abandon being aggressive (Guerra, Williams, & Sadek, 2011; Roseth and others, 2011). Proactive aggression, as you will see later, particularly the relational kind, helps children climb the social ranks (White, Jarrett, & Ollendick, 2013; Rodkin and others, 2013; Waasdorp and others, 2013). Without reactive aggression (fighting back when attacked), our species would never survive. Still, this disorganized, rage-

Understanding Highly Aggressive Children

You just saw that, as they get older, boys and girls typically get less openly aggressive. However, a percentage of children remain unusually aggressive into elementary school. These children are labeled with externalizing disorders defined by high rates of aggression. They are classified as defiant, antisocial kids.

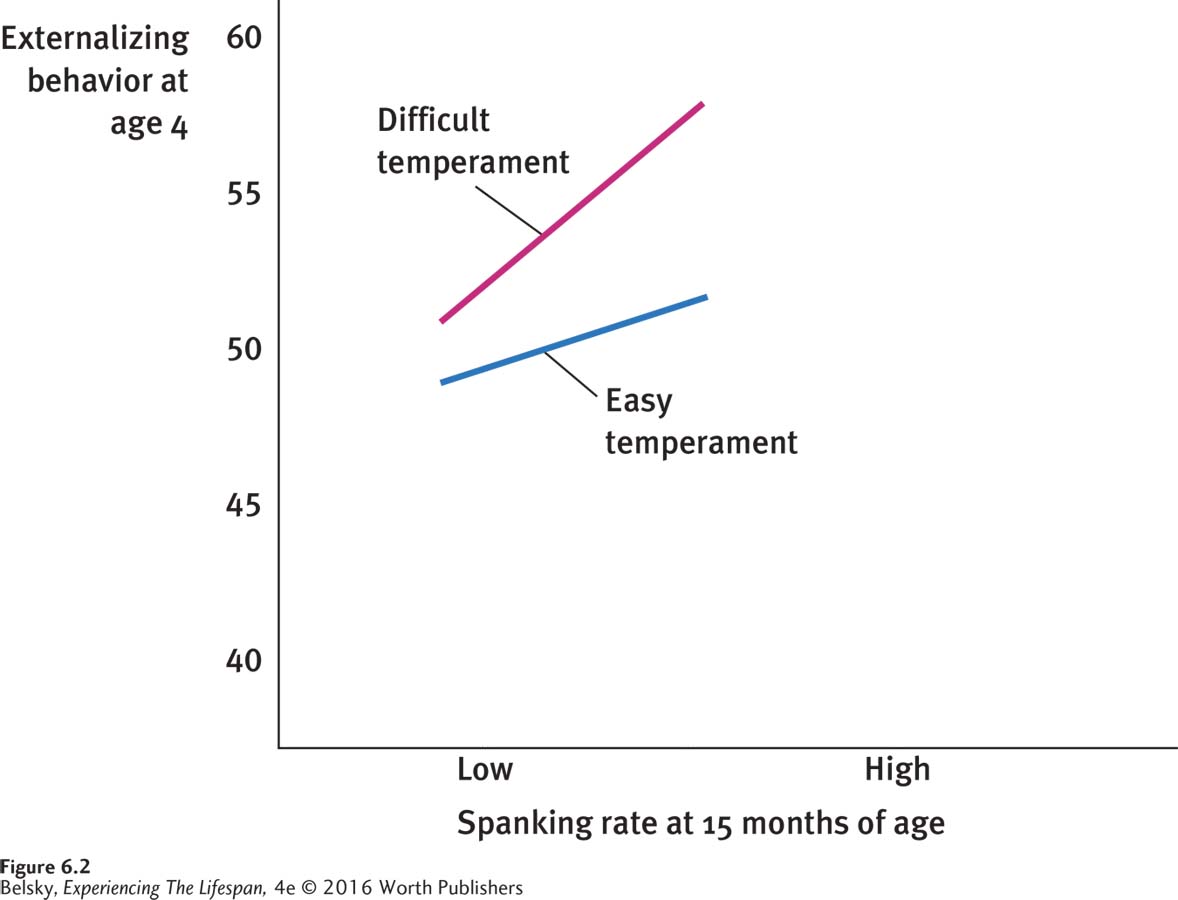

THE PATHWAY TO PRODUCING PROBLEMATIC AGGRESSION. Longitudinal studies suggest that there may be a poisonous two-

STEP 1: The toddler’s exuberant (or difficult) temperament evokes harsh discipline. When toddlers are exuberant (Degnan, Almas, & Fox, 2010), temperamentally fearless (Gao and others, 2010), and have problems regulating their attention (Kim & Deater-

181

STEP 2: The child is rejected by teachers and peers in school. Typically, the transition to being defined as an “antisocial child” occurs during early elementary school. As impulsive, by now clearly aggressive, children travel outside the family, they get rejected by their classmates. Being socially excluded is a powerful stress that provokes paranoia and reactive aggression at any age (DeWall and others, 2009; Lansford and others, 2010). Moreover, because aggressive children generally have trouble inhibiting their behavior (Runions & Keating, 2010), during elementary school they may start failing in their academic work (Romano and others, 2010). This amplifies the frustration (“I’m not making it in any area of life!”) and compounds the tendency to lash out (“It’s their fault, not mine!”).

A HOSTILE WORLDVIEW. As I just implied, reactive-

To summarize, let’s enter the mind of a reactive aggressive child, such as Mark in the opening chapter vignette. As a toddler, your fearless temperament continually got you into trouble with your parents. You have been harshly disciplined for years. In school, you are failing academically and shunned by your classmates. So you never have a chance to interact with other children and improve your social skills. In fact, your hostile attributional bias makes perfect sense. You are living in a “sea of negativity” (Jenson and others, 2004). And yes, the world is out to do you in!

182

Finally, as you saw in the Chapter 5 discussion of ADHD, there is a gender difference in the risk of being defined as “an acting-

How do boys and girls relate when they play? Now, I’ll turn to this question and others as we move to part two of this chapter: relationships.

Tying It All Together

Question 6.2

You interviewed a 4-

“My friend Megan is better at math than me.”

“Sometimes I get mad at my friends, but maybe it’s because I’m too stubborn.”

“I have a cat named Kit, and I’m the smartest girl in the world.”

c

Question 6.3

Identify which of the following boys has internalizing or externalizing tendencies and then, for one of these children, design an intervention using principles spelled out in this section: Ramon sees himself as wonderful, but he is having serious trouble getting along with his teachers and the other kids; Jared is a great student, but when he gets a B instead of an A, he decides that he’s “dumb” and gets too depressed to work.

Ramon = externalizing tendencies. Jared = internalizing tendencies. Suggested intervention for Ramon: Point out his realistic problems (“You are having trouble in X, Y, Z areas.”), but cushion criticisms with plenty of love. Suggested intervention for Jared: Continually point out reality (“No one can always get A’s. In fact, you are a fabulous student.”). Get Jared to identify his “hopeless and helpless” ways of thinking, and train him to substitute more accurate perceptions.

Question 6.4

Cotonia tells you that children need to be taught to be caring and helpful. Calista disagrees, saying that the impulse to be prosocial is built into human nature. In a sentence or two explain why both statements are correct.

Calista is right that the impulse to be prosocial seems biologically built in, as toddlers get joy from spontaneously performing helpful acts. Cotonia is correct, however, that adults need to nurture this behavior by modeling caring acts, being sensitive to a child’s emotions, defining the child as good, and using induction.

Question 6.5

A teacher wants to intervene with a student who has been teasing a classmate. Identify which statement is guilt-

“Think of how bad Johnny must feel.”

“If that’s how you act, you can sit by yourself. You’re not nice enough to be with the other kids.”

“I’m disappointed in you. You are usually such a good kid.”

a = induction; good for promoting prosocial behavior; b = shame; bad strategy; and c = guilt; good for promoting prosocial behavior

Question 6.6

Alyssa wants to replace Brianna as Chloe’s best friend, so she spreads horrible rumors about Brianna. Brianna overhears Alyssa dissing her and starts slapping Alyssa. Of the four types of aggression discussed in this section—

Alyssa = proactive, relational. Brianna = direct, reactive

Question 6.7

Mario, a fourth grader, feels that everyone is out to get him. Give the name for Mario’s negative worldview.

Mario has a hostile attributional bias.