6.3 Relationships

Think back to your days pretending to be a superhero or supermodel, getting together with the girls or boys to play, your best friends, and whether you were popular at school. Now, beginning with play, moving on to the play worlds of girls and boys, then friendships and popularity, and finally tackling bullying—

Play

Developmentalists classify children’s “free play” (the non-

183

Pretending: The Heart of Early Childhood

Fantasy play, or pretending, is different. Here, the child takes a stance apart from reality and makes up a scene, often with a toy or other prop. While fantasy play also can be immensely physical, this “as if” quality makes it unique. Children must pretend to be pirates or superheroes as they wrestle and run. Because fantasy play is so emblematic of early childhood, let’s delve into pretending in depth.

THE DEVELOPMENT AND DECLINE OF PRETENDING. Fantasy play first emerges in toddlerhood, as children realize that a symbol can stand for something else. In a classic study, developmentalists watched 1-

At about age 3, children transfer the skill of pretending with mothers to peers. Collaborative pretend play, or fantasizing together with another child, really gets going at about age 4 (Smolucha & Smolucha, 1998). Because they must work together to develop the scene, collaboratively pretending shows that preschoolers have a theory of mind—

Anyone involved with a young child can see these changes firsthand. When a 2-

Although fantasy play can continue into early adolescence, when children reach concrete operations, their interest shifts to structured games (Bjorklund & Pellegrini, 2002). At age 3, a child pretends to bake in the kitchen corner; at 9, he wants to bake a cake. At age 5, you ran around playing pirates; at 9, you tried to hit the ball like the Pittsburgh Pirates do.

THE PURPOSES OF PRETENDING. Interestingly, around the world, when children pretend, their play has similar plots. Let’s eavesdrop at a U.S. preschool:

BOY 2: I don’t want to be a kitty anymore.

GIRL: You are a husband?

BOY 2: Yeah.

BOYS 1 AND 2: Husbands, husbands! (Yell and run around the play house)

GIRL: Hold it, Bill, I can’t have two husbands.

BOYS 1 AND 2: Two husbands! Two husbands!

GIRL: We gonna marry ourselves, right?

(adapted from Corsaro, 1985, pp. 102–

Why do young children play “family,” and assume the “correct” roles when they play mommy and daddy? For answers, let’s turn to Lev Vygotsky’s insights.

184

Play allows children to practice adult roles. Vygotsky (1978) believed that pretending allows children to rehearse being adults. The reason girls pretend to be mommy and baby is that women are the main child-

Play allows children a sense of control. As the following preschool conversation suggests, pretending has a deeper psychological function, too:

GIRL 1: Yeah, and let’s pretend when Mommy’s out until later.

GIRL 2: Ooooh. Well, I’m not the boss around here, though. ’Cause mommies are the bosses.

GIRL 1: (Doubtfully) But maybe we won’t know how to punish.

GIRL 2: I will. I’ll put my hand up and spank. That’s what my mom does.

GIRL 1: My mom does too.

(adapted from Corsaro, 1985, p. 96)

While reading the previous two chapters, you may have been thinking that the so-

To penetrate the inner world of preschool fantasy play, sociologist William Corsaro (1985, 1997) went undercover, entering a nursery school as a member of the class. (No problem. The children welcomed their new playmate, whom they called Big Bill, as a clumsy, enlarged version of themselves.) As Vygotsky would predict, Corsaro found that preschool play plots often centered on mastering upsetting events. There were separation/reunion scenarios (“Help! I’m lost in the forest.” “I’ll find you.”) and danger/rescue plots (“Get in the house. It’s gonna be a rainstorm!”). Sometimes, play scenarios centered on that ultimate frightening event, death:

CHILD 1: We are dead, we are dead! Help, we are dead! (Puts animals on their sides)

CHILD 2: You can’t talk if you are dead.

CHILD 1: Oh, well, Leah’s talked when she was dead, so mine have to talk when they are dead. Help, help, we are dead!

(adapted from Corsaro, 1985 p. 204)

Notice that these themes are basic to Disney movies and fairy tales. From Finding Nemo, Bambi, and The Lion King to—

Play furthers our understanding of social norms. Corsaro (1985) found that death was a touchy play topic. When children proposed these plots, their partners might try to change the script. This relates to Vygotsky’s third insight about play: Although children’s play looks unstructured, it has boundaries and rules. Plots involving dead animals waking up make children uncomfortable because they violate the conditions of life. Children get especially uneasy when a play partner proposes scenarios with gory themes, such as cutting off people’s heads (Dunn & Hughes, 2001). Therefore, play teaches children how to act and how not to behave. Wouldn’t you want to retreat if someone showed an intense interest in decapitation while having a conversation with you?

185

Evaluating the Impact of Play

Many educators believe fantasy play is vital to developing our social and intellectual skills (see, for instance, Lindsey & Colwell, 2013). They agonize about the Internet revolution, worrying that hours glued to computers are robbing today’s preschoolers of the vital lessons that play provides (as reported in Lillard and others, 2013). Is pretend play important to developing a full human being?

In reviewing the data, scientists concluded the jury is out (Lillard and others, 2013). Many studies showing play’s value are correlational. So they may be confusing outcomes with causes. If preschoolers who pretend more are advanced socially and cognitively, does pretending cause these benefits, or do these qualities cause children to pretend more? Perhaps it is the myriad of adult activities that go along with fantasy play—

Girls’ and Boys’ Play Worlds

[Some] girls, all about five and a half years old, are looking through department store catalogues, . . . concentrating on what they call “girls’ stuff” and referring to some of the other items as “yucky boys’ stuff.” . . . Shirley points to a picture of a couch . . . “All we want is the pretty stuff,” says Ruth. Peggy now announces, “If you come to my birthday, every girl in the school is invited. I’m going to put a sign up that says, ‘No boys allowed!’” “Oh good, good, good,” says Vickie. “I hate boys.”

(adapted from Corsaro, 1997, p. 155)

Does this conversation bring back childhood memories of being 5 or 6? How does gender-

Exploring the Separate Societies

Visit a playground and observe children of different ages. Notice that toddlers show no sign of gender-

Now, go back to the playground and look at the way boys and girls relate. Do you notice that boy and girl play differs in the following ways?

BOYS EXCITEDLY RUN AROUND; GIRLS CALMLY TALK. Boys’ play is more rambunctious. Even during physical games such as tag, girls play together in calmer, more subdued ways (Maccoby, 1998; Pellegrini, 2006). The difference in activity levels is striking if you have the pleasure of witnessing one gender playing with the opposite sex’s toys. In one memorable episode, after my son and a friend invaded a girl’s stash of dolls, they gleefully ran around the house bashing Barbie into Barbie and using their booty as swords.

BOYS COMPETE IN GROUPS; GIRLS PLAY COLLABORATIVELY, ONE-

186

Boys and girls also differ in the way they relate. Boys try to establish dominance and compete to be the best. This competitive versus cooperative style spills over into children’s talk. Girl-

The stereotypic quality of girls’ fantasy play came as a shock when I spent three days playing with my visiting 7-

Boys’ and girls’ different play interests show why the kindergartners in the vignette at the beginning of this section came to hate those “yucky” boys. Another reason why girls turn off to the opposite sex is the unpleasant reception they get from the other camp. In observing at a preschool, researchers found that while active girls played with the boys’ groups early in the year, they eventually were rejected and forced to play with their own sex (Pellegrini and others, 2007). Therefore, boys are the first to erect the barriers: “No girls allowed!” Moreover, the gender barriers are generally more rigid for males.

BOYS LIVE IN A MORE EXCLUSIONARY, SEPARATE WORLD. My niece did choose to buy Barbies, but she also plays with trucks. She loves soccer and baseball, not just doing her nails. So, even though they may dislike the opposite sex, girls do cross the divide. Boys are more likely to avoid that chasm—

Now, you might be interested in what happened during my final day pretending with the pool party toys. After my niece said, “Aunt Janet, let’s pretend we are the popular girls,” our Barbies tried on fancy dresses (“What shall I wear, Jane?”) in preparation for a “popular girls” pool party, where the dolls met up to discuss—

What Causes Gender-

Why do children, such as my niece, play in gender-

A BIOLOGICAL UNDERPINNING. Ample evidence suggests that gender-

Actually, we can predict male gender-

Moreover girls exposed to high levels of testosterone before birth show more masculine interests as teens and emerging adults (Udry, 2000)! After taking maternal blood samples during the second trimester—

187

Females with high levels of prenatal testosterone, he discovered, were more interested in traditionally male occupations, such as engineering, than their lower-

THE AMPLIFYING EFFECT OF SOCIALIZATION. The wider world helps biology along. From the images displayed in preschool coloring books (Fitzpatrick & McPherson, 2010) to parents’ different toy selections for daughters and sons; from the messages beamed out in television sitcoms (Collins, 2011; Paek, Nelson, & Vilela, 2011) to teachers’ differential treatment of boys and girls in school (Chen & Rao, 2011)—everything brings home the message: Males and females act in different ways.

Peers play a powerful role in this programming. When they play in mixed-

Same-

THE IMPACT OF COGNITIONS. A cognitive process reinforces these external messages. According to gender schema theory (Bem, 1981; Martin & Dinella, 2002), once children understand their category (girl or boy), they selectively attend to the activities of their own sex.

When do we first grasp our gender label and start this lifelong practice of modeling our group? The answer is at about age 2 1/2, right after we begin to talk (Martin & Ruble, 2010)! Although they may not learn the real difference until much later (here it helps to have an opposite-

In sum, my niece’s beauty-

But are the gender norms loosening? U.S. children now feel it’s “unfair” to exclude boys from ballet class (Martin & Ruble, 2010). My students today often describe having had good friends of the other sex in elementary school, something that would never have occurred when I was a child. Do you think our less gender-

188

Friendships

This last question brings me friends. Why do children choose specific friends, and what benefits do childhood friendships provide?

The Core Qualities: Similarity, Trust, and Emotional Support

The essence of friendship is feeling similarity (Poulin & Chan, 2010). Children gravitate toward people who are “like them” in interests and activities (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011). In preschool, an active child will tend to make friends with a classmate who likes to run around. A 4-

In elementary school, children choose friends based on deeper similarities , such as shared morals (McDonald and others, 2014; Spencer and others, 2013). (“I like Josiah, because we think the same way about what’s right.”) As they reach concrete operations, children also develop the concept of loyalty (“I can trust Josiah to stand up for me”) and the sense that friends share their inner lives (Hartup & Stevens, 1997; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). Listen to these fourth and fifth graders describing their best friend:

He is my very best friend because he tells me things and I tell him things.

Me and Tiff share our deepest, darkest secrets and we talk about boys, when we grow up, and shopping.

Jessica has problems at home and with her religion and when something happens she always comes to me and talks about it. We’ve been through a lot together.

(quoted in Rose & Asher, 2000, p. 49)

These quotations would resonate with the ideas of personality theorist Harry Stack Sullivan. Sullivan (1953) believed that a chum (or best friend) fulfills the developmental need for self-

The Protecting and Teaching Functions of Friends

In addition to offering emotional support and validating us as people, friends stimulate children’s personal development in two other ways:

FRIENDS PROTECT AND ENHANCE THE DEVELOPING SELF. Perhaps you noticed this protective function in the quotation above in which the fourth grader spoke about how she helped her best friend when she had problems at home. Friends help insulate children from being bullied at school (Scholte, Sentse, & Granic, 2010). Close friends can even mute children’s genetic tendency toward developing depression (Brendgen and others, 2013) or reduce symptoms of ADHD (Becker and others, 2013).

189

FRIENDS TEACH US TO MANAGE OUR EMOTIONS AND HANDLE CONFLICTS. One reason is that friends offer on-

This is not to say that friends are always positive influences. They can bring out a child’s worst self by encouraging relational aggression (“We are best friends, so you can’t play with us”) and daring one another to engage in dangerous behavior (“Let’s sneak out of the house at 2 a.m.”) Best friends can promote an “us-

Popularity

Friendship involves relating with a single person in a close one-

Although children differ in social status in preschool, you may remember from childhood that “Who is popular?” becomes an absorbing question during later elementary school. Entering concrete operations makes children sensitive to making social comparisons. The urge to rank classmates according to social status is heightened by the confining conditions of childhood itself. In adulthood, popularity fades more into the background because we select our own social circles. Children must make it on a daily basis in a classroom full of random peers.

Who Is Popular and Who Is Unpopular?

How do children vary in popularity during the socially stressful later elementary school years? Here are the main categories researchers find when they ask third, fourth, or fifth graders to list the two or three classmates they like most and really dislike:

Popular children are frequently named in the most-

liked category and never appear in the disliked group. They stand out as being really liked by everyone. Average children receive a few most-

liked and perhaps one or two disliked nominations. They rank around the middle range of status in the class. Rejected children land in the disliked category often and never appear in the preferred list. They stand out among their classmates in a negative way.

What qualities make children popular? What gets elementary schoolers rejected by their peers?

Decoding Popularity

Especially in elementary school, popular children are often friendly and outgoing, prosocial, and kind (Mayberry & Espelage, 2007). However, starting as early as third grade, popularity can be linked to being relationally aggressive (Rodkin & Roisman, 2010; Ostrov and others, 2013).

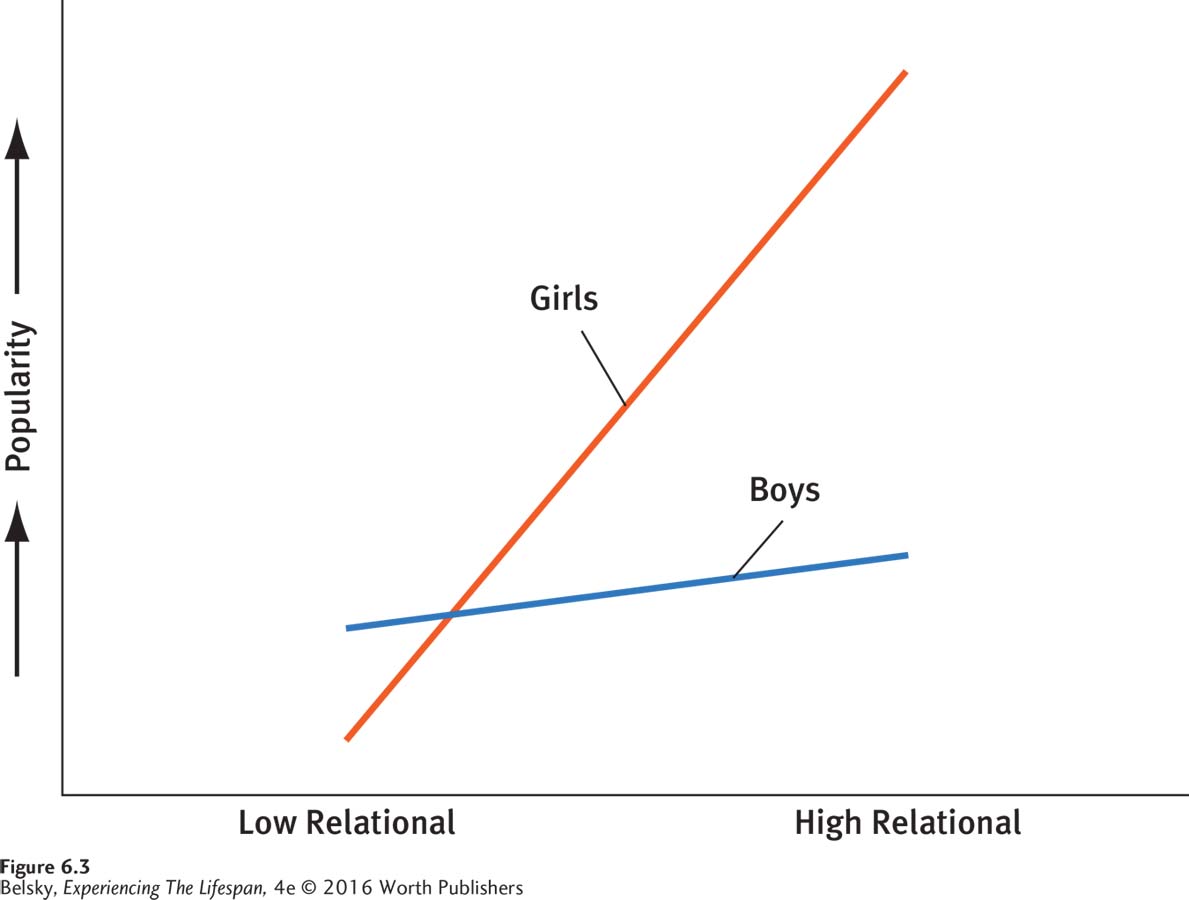

Figure 6.3, based on a study conducted in an inner city school, illustrates this unfortunate truth. Notice that relationally aggressive third to fifth graders were more apt to be rated as popular class leaders. But notice that the association between this poisonous interpersonal form of aggression and popularity was much stronger for girls—

190

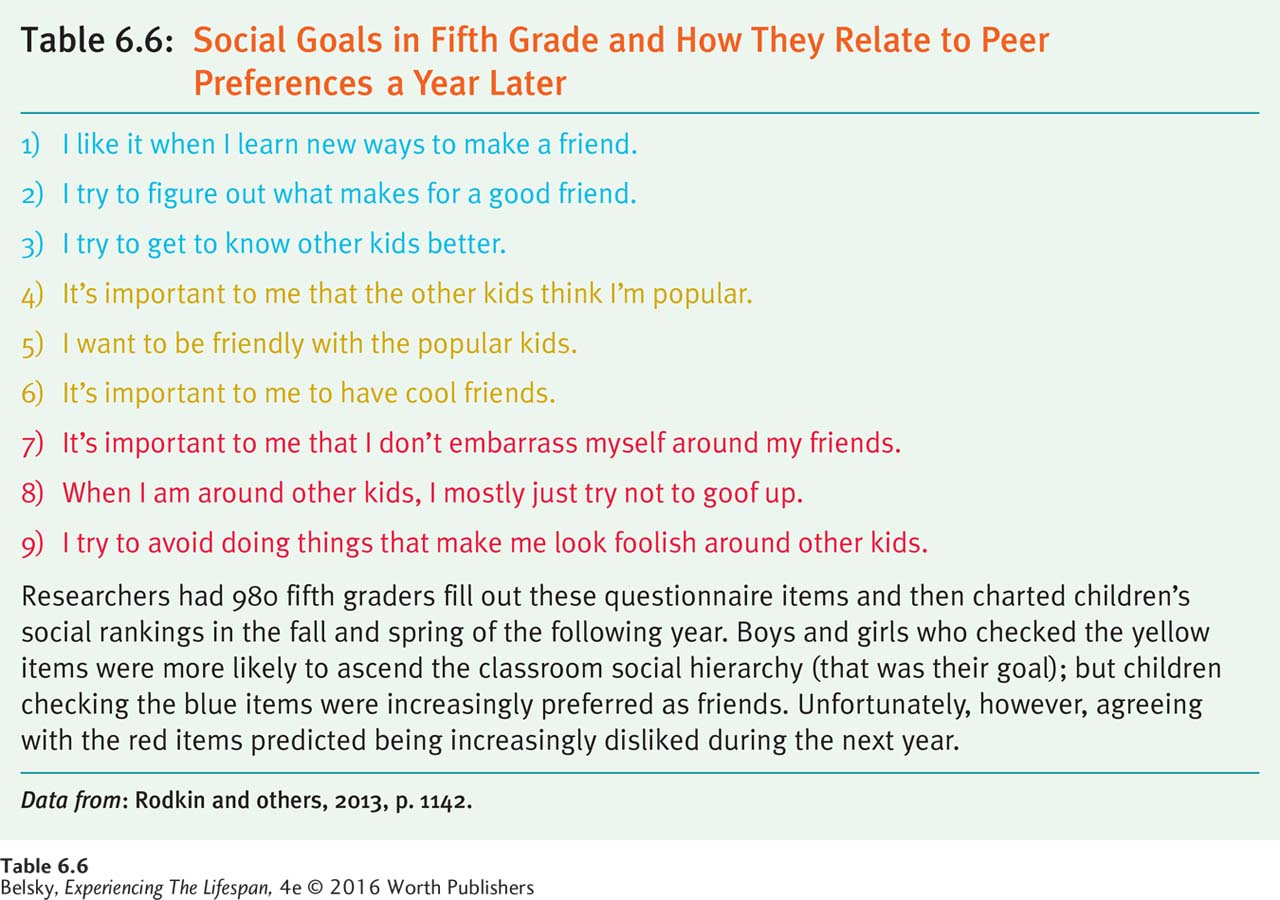

Relational aggression, as you will see in Chapter 9, is especially effective at propelling social mileage during preadolescence, when rebellion is in full flower and the pressure to form status cliques is intense (Werner & Hill, 2010; Witvliet and others, 2010). The good news is that the study described in Table 6.6 shows being in the popular crowd is different from being personally liked.

When researchers asked fifth graders questions such as those in the table, and then tracked their social status over time, boys and girls whose agenda was being popular (those agreeing with the yellow items) did rise in the social ranks. But as they reached sixth grade, the class increasingly preferred people with the blue agendas—

191

Now let’s focus on the third group of kids, fifth graders who checked the red items—

REJECTED CHILDREN HAVE EXTERNALIZING (AND OFTEN INTERNALIZING) PROBLEMS. Actually, the traits that universally land a child into the unpopular, rejected category are externalizing issues. Classmates shun boys and girls (like Mark in the introductory chapter vignette) who make reactive aggression a major life mode as early as age 5 (Hawley and others, 2007; Sturaro and others, 2011). Children with internalizing disorders may or may not be rejected. However, if a child—

Moreover, a poisonous nature-

A bidirectional process is also occurring. The child’s anxiety makes other children nervous. They get uncomfortable and want to retreat when they see this person approach. In response to your own awkward encounters, have you ever been tempted to walk in the opposite direction when you saw a very shy person approaching in the hall?

REJECTED CHILDREN DON’T FIT IN WITH THE DOMINANT GROUP. Children who stand out as different are also at risk of being rejected: boys and girls (like Moriah in the opening vignette) who don’t fit the gender stereotypes (Lee & Troop-

Exploring the Fate of the Rejected

Is childhood rejection a prelude to poor adult mental health? The answer is “sometimes.” Highly physically aggressive children are at risk for getting into trouble—

But there is variability, especially if a child has been rejected due to being “different” from the group. Consider an awkward little girl named Eleanor Roosevelt, who was socially rejected at age 8, or a boy named Thomas Edison, whose preference for playing alone got him defined as a “problem” child. Because they were so different, these famous adults were dismal failures during elementary school. To get insights into the fleeting quality of childhood peer status, you might organize a reunion of your fifth-

192

Bullying: A Core Contemporary Childhood Concern

You can get bullied because you are weak or annoying or because you are different. Kids with big ears get bullied. Dorks get bullied. . . . Teacher’s pet gets bullied. If you say the right answer in class too many times, you can get bullied.

(quoted in Guerra and others, 2011, p. 306)

Children who are different can excel in the proving ground of life. This is not the case on the proving ground of the playground. As you just read, being different, weak, socially awkward, or even “too good” is a recipe for bullying—being teased, made fun of, and verbally or physically abused by one’s peers.

As I implied earlier, bullying is “normal” as children jockey for power and status in the group. But the roughly 10 to 20 percent of children subject to chronic harassment fall into two categories. The first—

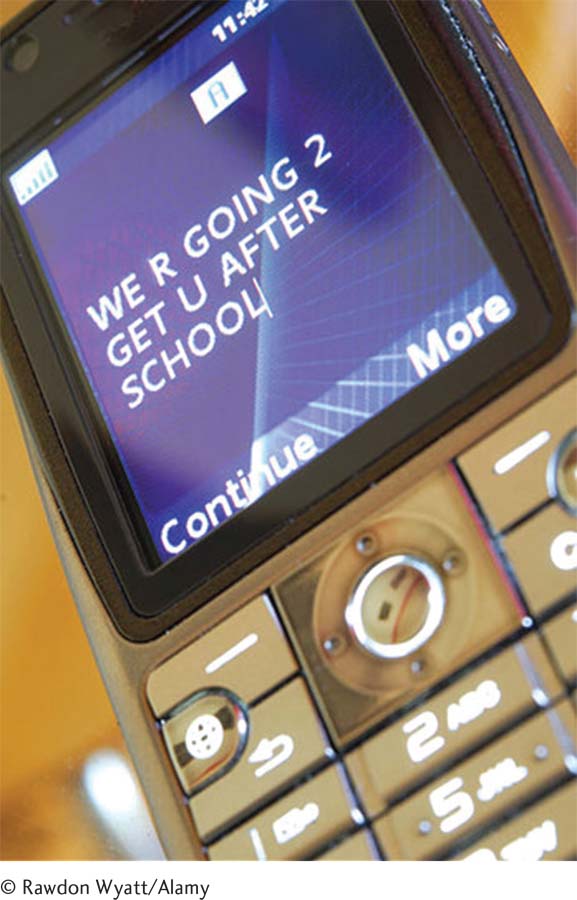

Home used to be a refuge for children harassed at school. No more! Facebook, cell phones, and the Internet have made bullying a 24/7 concern.

Experiencing the Lifespan: Middle-Aged Reflections on My Middle-Childhood Victimization

It was a hot August afternoon when the birthday present arrived. As usual, I was playing alone that day, maybe reading or engaging in a favorite pastime, fantasizing that I was a princess while sitting in a backyard tree. The gift, addressed to Janet Kaplan, was beautifully wrapped—

Around that time, the doorbell rang, and Cathy, then Ruth, then Carol, bounded up. “Your mother called to tell us she was giving you a surprise birthday party. We had to come over right away and be sure to wear our best dresses!” But their excitement turned to disgust when they learned that no party had been arranged. My ninth birthday was really in mid-

Why was I selected as the victim among the other third-

Although I did have friends, I was fairly low in the classroom hierarchy. Not only was I shy, but I was that unusual girl—

As an older woman, I still dislike status hierarchies and social snobberies. I’m not a group (or party) person. I far prefer talking one-

(P.S. I can honestly tell you that what happened to me in third grade is irrelevant to my life. I can’t help wondering, though. Suppose, as would be likely today, my classmates had been invited to my so-

193

Hot in Developmental Science: Cyberbullying

Cyberbullying, aggressive behavior repeatedly carried out via electronic media is potentially more toxic than traditional bullying in several ways: Broadcasting demeaning comments on Facebook ensures a large, amorphous audience that multiplies the victim’s distress. Sending a text anonymously can be scarier than confronting the person face to face. (“Who hates me this much?” “Perhaps it’s someone I trusted as a friend?”) (See Sticca & Perren, 2013.)

Moreover, the temptation to bully on-

Cyberbullying’s ease, nonstop quality, and scary public nature explain why teens see this behavior as worse than traditional bullying (Sticca & Perren, 2013). In one study of Canadian adolescents, involvement in cyberbullying—

Still, the same motives propel both cyberbullying and harassment of the face-

Actually, bullying—

The fact that the nicest children bully if the atmospheric conditions are right explains why school programs to attack bullying focus on changing the peer-

INTERVENTIONS: Attacking Bullying and Helping Rejected Children

In the Olweus Bully Prevention Program, for example, administrators plan a school assembly to discuss bullying early in the year. Then, they form a bullying-

Do the many bullying-

That’s why I’d like to end this chapter by returning to the classic recipients of this unfortunate, universal human activity—

In following a group of shy 5-

194

With toddlers at risk for externalizing disorders, as I’ve stressed earlier, providing loving, sensitive parenting is just as important (see Kochanska and others, 2010b). Adults also need to understand that, with active explorers, the same traits that can spell trouble can also be potential life assets. In an amazing decades-

How important are peer groups versus parents in shaping our behavior? What can schools do to generally help children thrive? Stay tuned as I delve into these questions—

Tying It All Together

Question 6.8

When Melanie and Miranda play, they love to make up pretend scenes together. Are these two girls likely to be about age 2, age 5, or age 9?

About age 5

Question 6.9

In watching boys and girls at recess in an elementary school, which two observations are you likely to make?

The boys are playing in larger groups.

Both girls and boys love rough-

and- tumble play. The girls are quieter and they are doing more negotiating.

a and c

Question 6.10

Erik and Maria are arguing about the cause of gender-

Erik can argue that gender-

Question 6.11

Best friends in elementary school (pick false statement): support each other/have similar moral values/encourage good behavior.

Friends can promote negative behavior (third alternative is wrong).

Question 6.12

Describe in a sentence or two the core difference between being popular and well liked.

Being popular refers to being in the in-

Question 6.13

Which of the following children is NOT at risk of being rejected in later elementary school?

Miguel, a shy, socially anxious child

Lauren, a tomboy who hates “girls’ stuff”

Nicholas, who lashes out in anger randomly at other kids

Elaine, who is relationally aggressive

d. (Unfortunately, relationally aggressive children can be popular.)

Question 6.14

(a) If a child (or adult) is being regularly bullied, name the core qualities that may be making this person an easy target. (b) Then, based on what you just read, describe in a sentence what you personally might do to change this situation.

(a) She may be highly aggressive, and is bullied, then victimized. Or, more typically, she is anxious, has few friends, and has trouble standing up for herself. (b) Speak up against the perpetrators while the group is around, or—