8.3 Sexuality

548: Immculate ros: Sex sex sex that all you think about?

559: Snowbunny: people who have sex at 16 r sick:

560: Twonky: I agree

564: 00o0CaFfEinNe; no sex until ur happily married—

566: Twonky: I agree with that too.

567: Snowbunny: me too caffine!

(quoted in Subrahmanyam, Greenfield, & Tynes, 2004, p. 658)

249

Sex is the elephant in the room of teenage life. Everyone knows it’s a top-

It is a minefield issue that contemporary young people negotiate in different ways. Take a poll of your classmates. Some people, as with the teenagers quoted above, may advocate abstinence, believing that everyone should remain a virgin until marriage. Others probably believe that having sex within a loving relationship is fine. Some students, if they are being honest, will admit, “I want to try out the sexual possibilities, but I promise to use contraception!”

This increasing acceptability (within limits) of carving out our own sexual path was highlighted in sexual surveys polling U.S. high school seniors in 1950, 1972, and 2000 (Caron & Moskey, 2002). Over the years, the number of seniors who decided, “It’s okay for teenagers to have sex,” shot up from a minority to more than 70 percent. But in the final turn-

Exploring Sexual Desire

David, age 14: Since a year or so ago, I just think about sex and masturbation ALL THE TIME! I mean I just think about having sex no matter where I am and I’m aroused all the time. Is that normal?

Expert’s reply: Welcome to the raging hormones of adolescence!

(adapted from a teenage sexuality on-

At what age does sexual desire begin? Although scientists had long assumed that the answer was during puberty, when testosterone is pumping through the body, research with homosexual adults caused them to rethink this idea. When gay women and men were asked to recall a watershed event in their lives—

How do sex hormone levels relate to teenagers’ sexual desires? According to researchers, we need a threshold androgen level to prime our initial feelings of desire (Udry, 1990; Udry & Campbell, 1994). Then, signals from the environment feedback to heighten our interest in sex. As children see their bodies changing, they think of themselves in a new, sexual way. Reaching puberty evokes a different set of signals from the outside world. A ninth-

250

Who Is Having Intercourse?

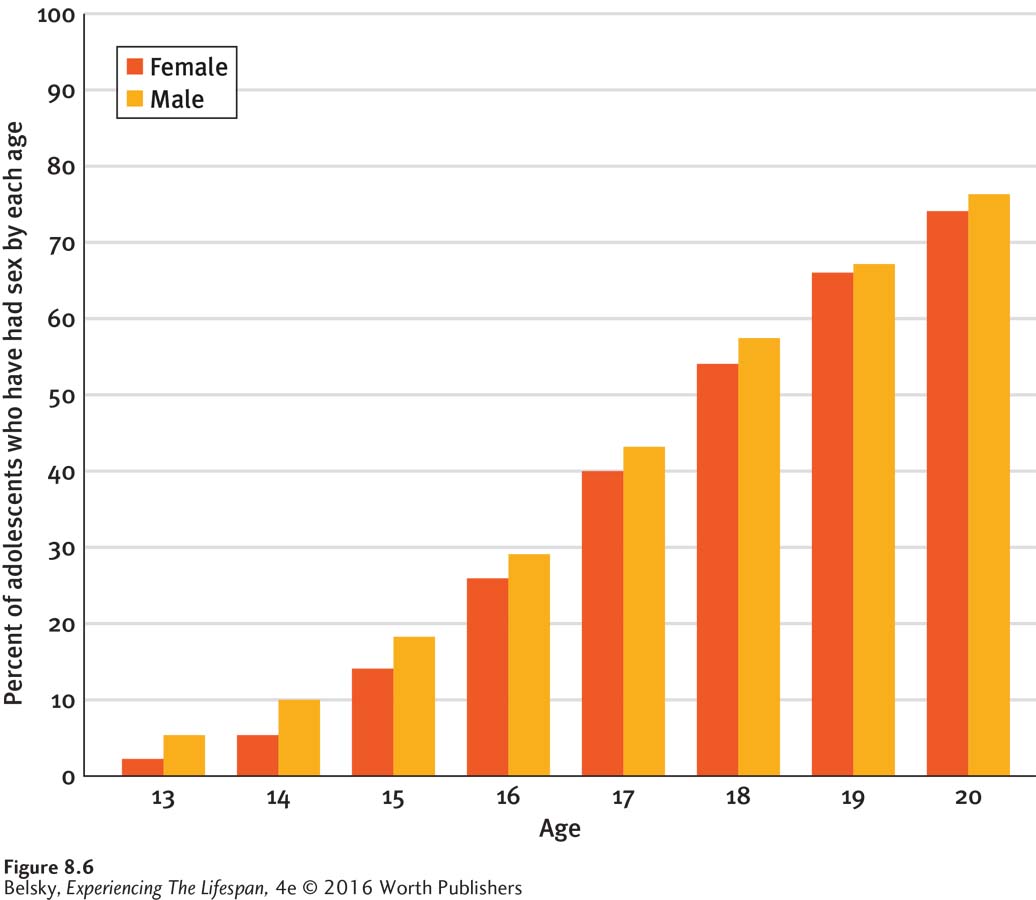

Today, the average age of first intercourse in the United States is age 17.8 for women and 18 for men (Finer & Philbin, 2014). But about 1 in 8 children make a “sexual debut” by age 15 (Guttmacher Institute, 2014; see also Figure 8.6).

As developmental systems theory suggests, a variety of forces predict making what researchers call an earlier transition to intercourse. One influence, for both boys and girls, is biological—

Personality makes a difference. Teens who are more impulsive, that is, those with externalizing tendencies, are apt to make the transition earlier (Moilanen and others, 2010). For European American girls, one study has suggested, having a risk-

This brings up the crucial role of peers. As I suggested earlier in the discussion of early-

251

You also might want to look at what a child watches on TV. In one fascinating study, researchers were able to predict which virgin boys and girls were likely to become sexually active from looking at their prior TV watching practices. Teens who reported watching a heavy diet of programs with sexually oriented talk were twice as likely to have intercourse in the next year as the children who did not (Collins and others, 2004).

Since sexual experiences (affairs, and so on) are a common media theme, we might predict that simply watching a good deal of television would promote an earlier transition to intercourse. We would be wrong. Teens are at special risk when they watch sexually suggestive programs in mixed gender groups (Parkes and others, 2013). With any media, it’s the content that matters—

Should we blame Cosmo reports such as “101 Ways to Drive Him Wild in Bed” for causing teenagers to start having sex? A bidirectional influence is probably in operation here. If a teenager is already interested in sex, that boy or girl will gravitate toward media that fit this passion. For me, the tip-

Who Are Teens Having Intercourse With?

Internet pornography celebrates anonymous sex. Many intercourse episodes on TV involve one-

Do adolescents who have sex with a person they are not dating hook up with a stranger or a good friend? For answers, we have an interview study in which researchers asked high schoolers in Ohio about their experiences with “noncommitted” sex (Manning, Giordano, & Longmore, 2006).

Of the teens who admitted to a nonromantic sexual encounter, 3 out of 4 reported that their partner was a person they knew very well. As one boy, who lost his virginity with his best friend described: “. . . I wouldn’t really consider dating her . . . but I’ve known her so long . . . anytime I feel down or she feels down, we just talk to each other” (quoted in Manning, Giordano, & Longmore, 2006, p. 469). Sometimes, the goal of having sex was to change a friendship to a romance: “After we started sleeping together . . . having a relationship came up.” Or, a teenager might fall into having sex with an ex-

So far, I have painted a benign portrait of these more casual, “friends with benefits” experiences. Wrong! Especially for girls, as you will read in Chapter 10, having one-

252

Hot in Developmental Science: Is There Still a Sexual Double Standard?

It’s different for boys, it’s like . . . if they have sex with somebody and then they are rewarded . . . and all the guys are just like “That’s great!” You have sex, and you’re a girl and it’s like “Slut.” That’s how it is . . .

(quoted in Martin, 1996, p. 86)

These complaints from a 16-

Basic to the stereotype of the double standard is the idea that girls are looking for committed relationships and that boys mainly want sex. The Ohio study, discussed in the previous section, offered a different view (Manning, Giordano, & Longmore, 2006). These interviews confirmed the statistics showing that teenage sex often happens within a committed relationship. In fact, feeling emotionally intimate, most teens reported, was the reason why both boys and girls decided to have sex. And, when a couple did take that step, the decision was often as difficult for guys as girls.

Read what a boy named Tim had to say:

That was something that I had been saving. I really wanted to save it for marriage, but I was curious and um she was special enough to me that I could give her this part of my life that I had been saving and um . . . She felt the same way because she wanted to wait till marriage, but we had decided and we was [were] both curious I guess and so it just happened”

(quoted in Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2010, p. 1007)

Moreover, when sex happened too quickly, as this next quotation shows, boys—

She was like . . . moving too fast . . . like she wanted to have sex with me in the car and I’m like “No” and then she starts touching me and I’m like “I’m cool, I’m cool; I got to go”. . . . And I did that and I left. . . . I was just, I don’t know; she wasn’t the girl I wanted to have sex with. . . . She wasn’t the right girl.

(quoted in Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2010, p. 1002)

In this study, both male and female teens reported that the decision to have sex was mutual; no one was pressuring anyone else. Or, as another boy named Tim delightfully put it:

So if a girl says yes and a boy says no; it’s a maybe. If a guy doesn’t know and a girl says yes, it’s yes . . . . If a girl says yes and a guy says yes, it’s yes . . . . So I think the women have more control because their opinion matters more in that situation.

(quoted in Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2010, p. 1007)

Is it really true, as Tim implies, that females are the main initiators (aggressors) when it comes to sex? Consider this revealing evidence from the virtual world: When researchers analyzed the profile photo comments on a popular Belgian social network site, they found that girls’ sexually-

Here are a few enthusiastic female posts that a boy named Kendeman’s photo evoked: “You are ****.. ... beautiful!” “I just wanted to say this because I think you are wonderfuuuuuul. Nobody can compete with you!” (Quoted from De Ridder & Van Bauwell, 2013, p. 576.)

So, even though the double standard seems firmly in operation, when we hear male teens brag about their exploits or listen to people make snide comments about “sluts and studs,” the reality is complex. Boys want sex in a loving relationship—

253

Wrapping Up Sexuality: Contemporary Trends

In summary, the news about teenage sexuality is good. Teenagers today feel more confident about charting their sexual path. Most sexual encounters occur in committed love relationships. The decision to have teenage sex is not typically taken lightly, but in a climate of caring and mutual decision making for both girls and boys. Girls have far more control in the sexual arena than we think!

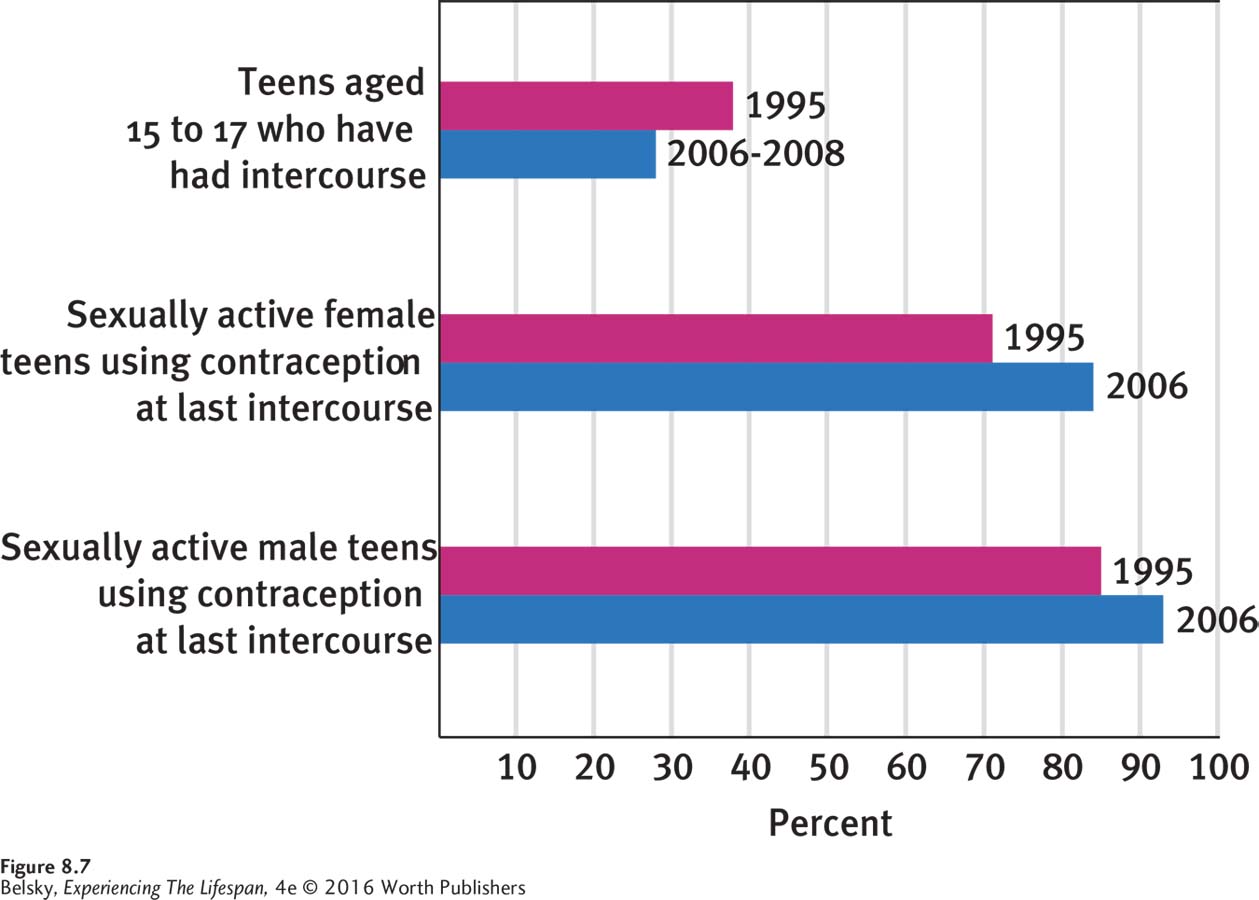

These changes are mirrored in the encouraging statistics in Figure 8.7: fewer U.S. teenagers are having intercourse, and most teens report they use condoms when they do have sex. In fact, over a decade spanning the late 1990s to the early twenty-

Still, with regard to teenage pregnancy, the United States ranks near the pinnacle of the developed world. While European teens have comparable levels of sexual activity as U.S. adolescents, E.U. pregnancy rates put the United States to shame (Guttmacher Institute, 2014; McKay & Barrett, 2010). Compared to Western Europe, the prevalence of gonorrhea and chlamydia among U.S. adolescents is very high (Guttmacher Institute, 2011b).

INTERVENTIONS: Toward Teenager-Friendly Sex Education

These less-

Actually, around the world, school sex education offers a patchwork of slipshod strategies. Some school systems and countries teach only abstinence. Others discuss contraception and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Some teach teens about alternative lifestyles, such as being gay. Other nations teach nothing about sex in school at all. The reason comes as no surprise: From Canada, to Australia (Goldman & Coleman, 2013), to South Africa (Francis & DePalma, 2014), parents are deeply divided about what to say to teens about sex (Elliot, 2012).

254

One classic fear is that teaching contraception might encourage teens to have intercourse. This we know is not true. When Irish researchers compared young people in that nation who had high school sex education and a group with no instruction, girls and boys exposed to sex education classes became sexually active at an older age than their peers (Bourke and others, 2014).

Some of you reading the above information might say, “Ok, Dr. Belsky, perhaps that’s true, but having my child’s school discuss contraception is ethically distasteful, because I believe abstinence is the only way to go.” Perhaps everyone might agree with the following alternate approach.

For decades, teens have complained that high school sex-

Therefore, stale controversies about whether to teach contraception may be missing the boat. In contrast to the alarmist messages, we now understand that most teens are not passionate to have random sex. Young people are lusting—

Designing an optimal romance (or relationship) class depends on knowing how adolescents think and reason about life. The next chapter focuses on this topic in depth.

Tying It All Together

Question 8.11

When a mother asks you when her son may experience his first sexual feelings, you should answer: around age 10, before the physical signs of puberty occur/around age 13 or 14/in the middle of puberty/toward the end of puberty.

around age 10, before the physical signs of puberty occur

Question 8.12

Your friend thinks her teenage daughter may be having sex. So she asks for your opinion. All the following questions are relevant for you to ask except:

Are your daughter’s friends having sex?

Is your daughter’s school teaching abstinence?

Is your daughter watching sexually explicit cable channels with her male friends and reading Cosmo?

Does your daughter have an older boyfriend?

b

Question 8.13

Tom is discussing trends in teenage sex and pregnancy. Which two statements should he make?

Today, sex often happens in a committed relationship.

Today, the United States has lower teenage pregnancy rates than other Western nations.

In recent decades, rates of teenage births in the United States have declined.

Today, boys are still the sexual initiators.

a and c

Question 8.14

Imagine you are designing a “model” sex-

encouraging abstinence

providing information about birth control and STDs

discussing how to have loving relationships

c, discuss how to have loving relationships

255