4.3The Double Helix Facilitates the Accurate Transmission of Hereditary Information

The Double Helix Facilitates the Accurate Transmission of Hereditary Information

The double-

115

Differences in DNA density established the validity of the semiconservative replication hypothesis

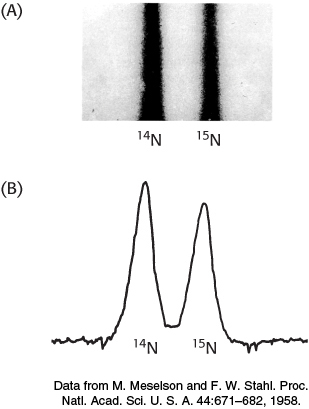

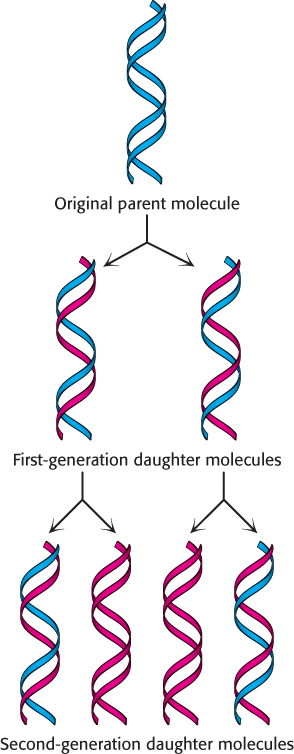

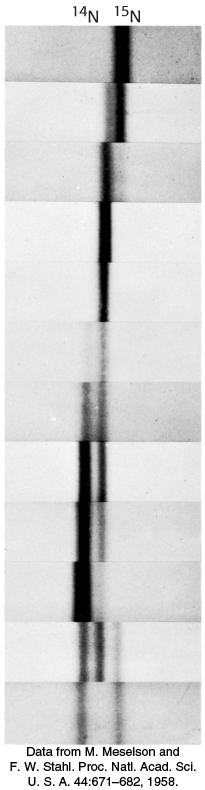

Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl carried out a critical test of this hypothesis in 1958. They labeled the parent DNA with 15N, a heavy isotope of nitrogen, to make it denser than ordinary DNA. The labeled DNA was generated by growing E. coli for many generations in a medium that contained 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source. After the incorporation of heavy nitrogen was complete, the bacteria were abruptly transferred to a medium that contained 14N, the ordinary isotope of nitrogen. The question asked was: What is the distribution of 14N and 15N in the DNA molecules after successive rounds of replication?

The distribution of 14N and 15N was revealed by the technique of density-

DNA was extracted from the bacteria at various times after they were transferred from a 15N to a 14N medium. Analysis of these samples by the density-

116

The absence of 15N DNA indicated that parental DNA was not preserved as an intact unit after replication. The absence of 14N DNA indicated that all the daughter DNA derived some of their atoms from the parent DNA. This proportion had to be half because the density of the hybrid DNA band was halfway between the densities of the 14N DNA and 15N DNA bands.

After two generations, there were equal amounts of two bands of DNA. One was hybrid DNA, and the other was 14N DNA. Meselson and Stahl concluded from these incisive experiments that replication was semiconservative, and so each new double helix contains a parent strand and a newly synthesized strand. Their results agreed perfectly with the Watson–

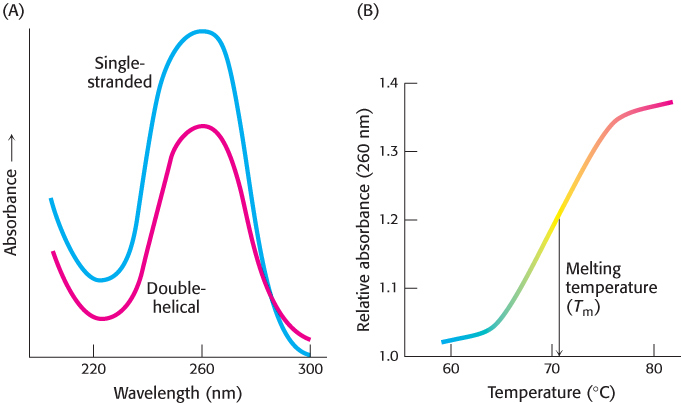

The double helix can be reversibly melted

During DNA replication and transcription, the two strands of the double helix must be separated from each other, at least in a local region. The two strands of a DNA helix readily come apart when the hydrogen bonds between base pairs are disrupted. In the laboratory, the double helix can be disrupted by heating a solution of DNA or by adding acid or alkali to ionize its bases. The dissociation of the double helix is called melting because it occurs abruptly at a certain temperature. The melting temperature (Tm) of DNA is defined as the temperature at which half the helical structure is lost. Inside cells, however, the double helix is not melted by the addition of heat. Instead, proteins called helicases use chemical energy (from ATP) to disrupt the helix (Chapter 28).

Stacked bases in nucleic acids absorb less ultraviolet light than do unstacked bases, an effect called hypochromism. Thus, the melting of nucleic acids is readily monitored by measuring their absorption of light, which is maximal at a wavelength of 260 nm (Figure 4.23).

Separated complementary strands of nucleic acids spontaneously reassociate to form a double helix when the temperature is lowered below Tm. This renaturation process is sometimes called annealing. The facility with which double helices can be melted and then reassociated is crucial for the biological functions of nucleic acids.

117

The ability to melt and reanneal DNA reversibly in the laboratory provides a powerful tool for investigating sequence similarity. For instance, DNA molecules from two different organisms can be melted and allowed to reanneal, or hybridize, in the presence of each other. If the sequences are similar, hybrid DNA duplexes, with DNA from each organism contributing a strand of the double helix, can form. The degree of hybridization is an indication of the relatedness of the genomes and hence the organisms. Similar hybridization experiments with RNA and DNA can locate genes in a cell’s DNA that correspond to a particular RNA. We will return to this important technique in Chapter 5.