33.5Touch Includes the Sensing of Pressure, Temperature, and Other Factors

Touch Includes the Sensing of Pressure, Temperature, and Other Factors

Like taste, touch is a combination of sensory systems that are expressed in a common organ—

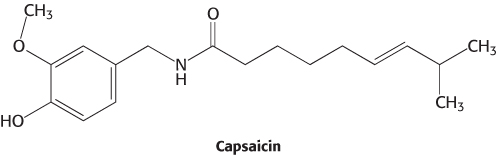

Studies of capsaicin reveal a receptor for sensing high temperatures and other painful stimuli

Our sense of touch is intimately connected with the sensation of pain. Specialized neurons, termed nociceptors, transmit signals from skin to pain-

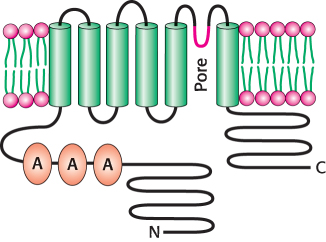

Early research suggested that capsaicin would act by opening ion channels that are expressed in nociceptors. Thus, a cell that expresses the capsaicin receptor should take up calcium on treatment with the molecule. This insight led to the isolation of the capsaicin receptor with the use of cDNA from cells expressing this receptor. Such cells had been detected by their fluorescence when loaded with the calcium-

978

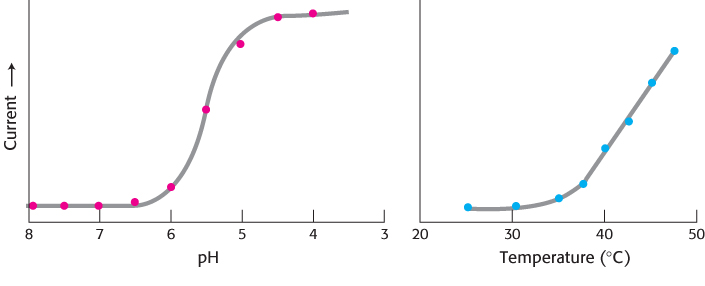

Currents through VR1 are also induced by temperatures above 40°C and by exposure to dilute acid, with a midpoint for activation at pH 5.4 (Figure 33.36). Temperatures and acidity in these ranges are associated with infection and cell injury. The responses to capsaicin, temperature, and acidity are not independent. The response to heat is greater at lower pH, for example. Thus, VR1 acts to integrate several noxious stimuli. We feel these responses as pain and act to prevent the potentially destructive conditions that cause the unpleasant sensation. Studies of mice that do not express VR1 suggest that this is the case; such mice do not mind food containing high concentrations of capsaicin and are, indeed, less responsive than control mice to normally noxious heat. Plants such as chili peppers presumably gained the ability to synthesize capsaicin and other “hot” compounds to protect themselves from being consumed by mammals. Birds, which play the beneficial role of spreading pepper seeds into new territory, do not appear to respond to capsaicin.

Because of its ability to simulate VR1, capsaicin is used in pain management for arthritis, neuralgia, and other neuropathies. How can a compound that induces pain assist in its alleviation? Chronic exposure to capsaicin overstimulates pain-

Because of its ability to simulate VR1, capsaicin is used in pain management for arthritis, neuralgia, and other neuropathies. How can a compound that induces pain assist in its alleviation? Chronic exposure to capsaicin overstimulates pain-